“The most dangerous enemy of truth and freedom among us is the compact majority.”

—Dr. Stockmann in Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People

1.

More Democracy, More Extremism?

Last summer, on the evening of August 16, 2014, Norway’s largest tabloid, Verdens Gang, posted on its website an extended videotaped interview with Ubaydullah Hussain, the spokesman of a small Islamist fringe group called the Prophet’s Umma (umma refers to the community of believers in Islam). A twenty-nine-year-old Norwegian of Pakistani descent, Hussain grew up in a successful immigrant household in an Oslo suburb and had begun a promising career as a soccer referee in the Norwegian leagues—one newspaper described him as “bland and sociable.” Around 2011, however, he began associating with radical Islamists and was later expelled from the sport for making extremist comments on social media. In the VG interview, appearing in a black skullcap and dark tunic with a Taliban-style beard, he declared his “absolute” support for ISIS and his belief that Norway should be governed by sharia law.

What made these comments particularly startling, however, was the way Hussain was able to frame them in reference to Norwegian concepts of political rights. Largely unchallenged by the VG journalist, he used the forty-three- minute interview to argue calmly against Western “propaganda” about the Islamic State and to assert the right of Norwegians to travel to Syria to join it. He also defended ISIS’s practice of decapitating nonbelievers. “Beheading is not torture, people die instantly,” he said, “as opposed to what the West does with Muslim prisoners.” Three days later, on August 19, ISIS announced the beheading of the American journalist James Foley.

Norway seems an unlikely place for Islamist extremism. Exceptionally wealthy, this small Nordic country has an unemployment rate of 3.7 percent and offers enviable welfare benefits to citizens and new immigrants alike. Though Muslims account for less than 5 percent of the country’s five million citizens, there are both Shias and Sunnis, including sizable Pakistani and Somali communities, as well as smaller numbers with Iranian, Turkish, and North African backgrounds. This diverse population is comparatively well integrated. Norway does not have radical mosques and several Muslims serve in Parliament. On the main street of Grønland, the central Oslo neighborhood that is the epicenter of the Muslim community, there are Islamic centers and halal butchers, but also an upscale bar serving high-end beer from a local brewery.

In recent months, however, European governments have become alarmed by the flow of more than three thousand of their citizens to Syria to join jihadist groups there; and following the tragic Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris in early January, new questions have emerged about the ability of European nations to cope with terror threats from within their own populations. Norway has been no less affected than its neighbors. In the days since the Paris killings, some Norwegian commentators, including several Muslims, have defended Charlie Hebdo’s right to publish offensive cartoons even if they find them distasteful. But in early February, security officials told the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet that as many as 150 Norwegians have joined jihadist groups in Syria, among them several teenage girls and a Prophet’s Umma member now described as a senior lieutenant of ISIS; and in comments to the Norwegian press, Ubaydullah Hussain, the spokesman for the Prophet’s Umma, said that, under sharia law, the death penalty is “entirely appropriate” for those who lampoon the Prophet.

Already in 2010, during an earlier demonstration against a Norwegian newspaper for publishing a Muhammad caricature, another Norwegian Islamist warned that it could bring about a “September 11 on Norwegian soil.” This was followed, in 2012, by a letter sent by an anonymous Islamist group to then Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg and Foreign Minister Jonas Gahr Støre demanding that the Grønland neighborhood in Oslo be turned into an “Islamic State.” Last summer, the Norwegian government announced that it had uncovered a terrorist plot by “persons associated with an extremist group in Syria.” And in November, in its latest threat assessment, the PST, Norway’s domestic intelligence agency, put the likelihood of an extremist attack in the next twelve months at well over 50 percent. As the prominent Norwegian journalist Åsne Seierstad put it when I met her in Oslo in late August, “Is there something we are doing wrong?”

The question is particularly vexing for Norwegians because, amid the alleged threats from jihadists, their country has been recovering from an actual act of devastating terrorism—from an avowed enemy of Islam. The meticulously planned July 22, 2011, massacre by the ethnic Norwegian Anders Behring Breivik—the subject of Seierstad’s chilling new book—was the worst mass killing in Norwegian history. First he set off a car bomb in front of the prime minister’s office in Oslo, an explosion that killed eight people and left more than two hundred people injured. (As with the Oklahoma City bombing, he had hoped to make the entire building collapse but was unable to park close enough.) He then proceeded to a summer youth camp run by the ruling and long-dominant Labor Party on the small island of Utøya, near the capital. Disguised as a PST officer, he methodically killed sixty-nine more people with high-powered rifles—most of them teenagers, including a number with immigrant or refugee backgrounds.

Advertisement

In a 1,518-page manifesto released on the Internet hours before the attacks, Breivik made clear that one of his main preoccupations was the “Islamic colonization” of the country abetted by the Labor Party’s “multiculturalist” immigration policies. In murdering so many children, he later explained, he aimed “to kill the party leaders of tomorrow.” Shortly after his arrest he also told Norwegian police that “it’s the media who are most to blame…because they didn’t publish my views.” Yet his extraordinary violence also bore uncanny similarities to the Islamic extremism he purported to hate.

During his trial in 2012, Breivik revealed that his three principal targets at Utøya were Gro Harlem Brundtland, Norway’s first female prime minister, who was on the island earlier that day; then Foreign Minister Støre, one of the country’s most prominent advocates of pluralism and diversity, who visited a day earlier; and Labor youth leader Eskil Pedersen, who managed to flee shortly after Breivik arrived. Once the killer had captured them, he had planned to force the hostages down on their knees while he read a “judgment” against them; then he would decapitate each of them with a bayonet. All this would be filmed on his iPhone and posted on the Internet. “It is a strategy taken from al-Qaeda,” Breivik told the court, explaining that Christian Europe had had an earlier tradition of beheading. “It is a very potent psychological weapon.”

It is hard to overstate the trauma caused by the July 22 attacks to Norway’s political establishment. In a stirring speech three days after the massacre, Prime Minister Stoltenberg vowed to handle the crisis with frank discussion rather than a new security state. “We will not allow the fear of fear to silence us,” he said. “More openness, more democracy…. That is us. That is Norway.” But in 2012 an official investigation found that the police and security forces’ response during the attacks had been seriously flawed, and in September 2013, the Labor Party was voted out of office. It was replaced by the Conservative Party in coalition for the first time with the populist anti-immigration Progress Party—a party that Breivik belonged to in the early 2000s and that is known for, among other things, its warnings about “stealth Islamicization.”

Even as the nation recoiled in horror from Breivik’s atrocity, the Norwegian press began devoting increasing attention to the Prophet’s Umma, though its few dozen followers make up a tiny fraction of the Muslim community. On the weekend that Ubaydullah Hussain’s defense of beheadings was posted on VG’s website last summer, one Norwegian activist told me, it was accessed more than 500,000 times, a number equal to roughly one tenth of Norway’s population.

On August 25, incensed by the VG interview’s recklessly misleading impression that most Norwegian Muslims support ISIS, a group of Muslim youth organized a large march against extremism from the Grønland neighborhood to Oslo’s central square. When the marchers reached the steps of the Norwegian Parliament—many bearing signs that said “NO2ISIS”—a rare assemblage of government leaders came out to greet them: Norway’s Conservative prime minister, Erna Solberg; the ministers of finance, justice, and social affairs; the leaders of every major Norwegian party; and numerous members of Parliament. Along with several Muslim leaders and a nineteen-year-old Norwegian-Iraqi woman who helped instigate the protest, the prime minister herself gave a speech, as did Jonas Gahr Støre, who, as the new head of the Labor Party, was now the presumptive leader of the opposition.

As with the response to Breivik’s Utøya massacre, this rousing demonstration of national unity seemed to evince the qualities that have made Norwegian social democracy so distinctive. Rather than calling for a crackdown on extremist groups, political leaders were joining with the Muslim community to show that Norwegians do not endorse the values of the Prophet’s Umma; speech had been countered by more speech. Notwithstanding the legacy of Breivik, security was light, and during the speeches, I and other journalists mingled freely with government ministers on the steps of the Parliament. Above all, several Norwegian officials told me, was the fact that the march had been initiated by Muslims themselves.

Advertisement

Yet other tensions within the Muslim community seemed to be overlooked. A Norwegian Muslim journalist observed that the rally had been instigated by Shia activists and that their failure to highlight Shia extremism had turned off mainstream Sunnis. Meanwhile, Ubaydullah Hussain remained free to promote jihad and endorse attacks like the recent Paris killings.

Others wondered why it was so easy for government leaders to stand up against extremism, but so hard to ask whether their own policies might be contributing to it. Why were Muslim Norwegians going to Syria to fight in the first place? And why was no one talking about Breivik?

2.

The Happy Moment

By almost any conventional measure, Norway is a blissful anomaly. According to the International Monetary Fund, the country’s GDP per capita is now more than $100,000—more than Qatar’s and second only to tiny Luxembourg’s; remarkably for an oil country, it also has low income inequality, thanks to a highly redistributive tax system. Norway is the most democratic country in the world, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s measure of sixty different political criteria, and it outperforms any other nation on measures of gender equality. Along with Solberg, the current prime minister, many of the most important cabinet members are women, including the ministers of finance, defense, trade, environment, and social inclusion.

Nor does the country suffer from the urban malaise that plagues many of its neighbors. Its small population occupies one of the largest countries in Europe, and its uncrowded cities are known for their clean water and air. Despite vast oil resources, Norway gets 99 percent of its electricity from hydropower and produces so little waste that, along with Sweden, it has begun importing garbage from other countries to fuel its incinerators. Almost every child is educated through the public education system. Norwegian prisons are considered models of enlightened rehabilitation. And on measures of “social trust”—the degree to which people say they trust others and their governments—Norway routinely ranks first or second in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Since 2008, the tax returns of every citizen have been published in a searchable online database.

These remarkable achievements, however, belie a more complicated relationship to the outside world. With more than 100,000 kilometers of rugged coastline, Norwegians have a tradition of seafaring and exploration going back to the Viking age. Yet until oil was discovered in the second half of the twentieth century, the country was very poor, with the result that there was a long tradition of emigration, while few foreigners came in. Even now, while Norway relies on tens of thousands of migrant laborers from other European countries, including Poland and the Baltic states, it has long been careful about accepting non-Europeans, who are admitted largely on humanitarian grounds and whose numbers the current administration has strictly limited. Thus while the Norwegian government sends more humanitarian aid abroad per capita than any country, it takes in far fewer asylum seekers than neighboring Sweden; last summer, the government rejected 123 Syrian refugees because they were deemed too burdensome for the Norwegian health system.

To a large degree, Norway’s comprehensive approach to social democracy was built on the assumption of a small and cohesive native population. The most important parts of the welfare state—health insurance, child allowances, schooling, employment insurance, housing provisions—were put into effect between the late 1940s and the early 1960s when, as the immigration scholars Grete Brochmann and Anniken Hagelund observe, “practically no one came to Norway from outside northern Europe.” Not coincidentally, some of the right-wing ideologues who influenced Breivik idealize this era as a time of national “purity” that ended when immigration began.

The lack of significant diversity in the postwar years also meant that there was a broad cultural and political consensus for the values endorsed by the state. During this “happy moment,” the historian Francis Sejersted writes in his major study, The Age of Social Democracy (2011), the active promotion of individual rights did not seem to conflict with far-reaching government intervention in society. Since people generally wanted the same things, both projects could “mold” Norwegians into a strongly unified nation. With the arrival of immigrants from vastly different backgrounds, however, the assumption that Norwegian freedoms would produce Norwegian social democrats began to break down.

3.

Cupcake Jihad

According to several researchers I met in Oslo, many of the current tensions surrounding immigration and Islam can be traced to political forces that emerged after September 11, 2001. Although fascism had a brief vogue in Norway in the 1930s and the collaborationist Quisling government ruled during the Nazi years, far-right ideology never attracted more than marginal interest in Norway. With the arrival of growing numbers of non-European refugees in the 1980s and 1990s, the anti-immigration Progress Party began to gain considerable support. But the party was mostly shunned by the political establishment, and the very few Norwegians who belonged to the hard right were closely monitored by the PST. “Right-wing extremism was our number one priority,” a PST intelligence analyst told me. “Then 9/11 came along and our priorities shifted.”

Following the revelation that Muslims living in Europe had planned the September 11 attacks, more overt opposition to Muslims and Islam began to enter mainstream Norwegian politics. Sometimes it came from the left, as secular feminists in particular criticized the practice of wearing headscarves and the perceived subjugation of Muslim women. In 2006, Norway’s Labor government was rebuked by some commentators in the national press for not defending the republication of the Danish Muhammad cartoons. By 2009, a popular conservative Norwegian website called Document.no—to which Anders Breivik was an occasional contributor—took a lead part in pressuring Parliament to drop proposed new restrictions on criticism of religions, and the Progress Party, with its strident views on immigration and Islam, was attracting up to 30 percent of Norwegian voters in some polls.

Further to the right was a small but active online community of “counter-jihadists,” hard-line anti-Islam commentators who supported the so-called Eurabia thesis—the theory that there was a conspiracy to Islamicize Europe. In the mid-2000s, Anders Breivik, by this point a failed entrepreneur who had given up on the Progress Party and was spending hours playing World of Warcraft, became deeply influenced by these writers. Above all—as described by Aage Borchgrevink in A Norwegian Tragedy—he admired Fjordman, a mysterious Norwegian blogger who had written a book called Defeating Eurabia. In real life, Fjordman turned out to be Peder Nøstvold Jensen, a young journalist from a leftist family who had studied in Cairo before becoming a prolific right-wing ideologue. As Fjordman, he argued that, even more than Islam itself, it was Norway’s “cultural Marxist elites” who were the “enemy number one” because they “flooded our countries with enemies and forced us to live with them.”

Amid the increasing hostility, meanwhile, many young second-generation Norwegian Muslims began taking a new interest in their religious identity and networking with Muslims elsewhere in Europe. The most striking result was the launch in 2008 of Islam Net, an online-based youth organization with an ultraconservative Salafist ideology—it sought to reinvigorate the Muslim community through such strictures as gender segregation and prayer and rigorous adherence to Islamic law.

Founded by a Norwegian engineering student of Pakistani background named Fahad Quereshi, Islam Net was soon attracting as many as several thousand people to its conferences—a remarkable number for a Salafist organization in a small Nordic country—to which it brought major Salafist clerics from Western Europe and the United States. “The preachers they started to invite were already famous on YouTube,” Marius Linge, a Norwegian researcher of Islam who has made a detailed study of the group, told me. “These were the coolest guys around.”

From the outset, Islam Net renounced violence, but the puritanical version of Islam it promoted—and its strong emphasis on proselytizing others—raised suspicions that it was providing a pathway to further radicalization. Some Islam Net members have gone on to join the far more extreme Prophet’s Umma, which since its emergence in 2011 has followed Islam Net’s emphasis on networking with like-minded Islamists on the Web; for example, the Prophet’s Umma has joined in regular closed online meetings with Anjem Choudary, a silver-tongued British Islamist who is well known for his support for the Syrian jihad and for ISIS in particular.

Notably, Islam Net has also attracted many young women who have themselves taken the lead in adopting such practices as the niqab, or full head-covering. Hardly any Norwegian Muslims come from countries where the niqab is worn. But according to Linda Alzaghari, a Norwegian activist and Muslim convert who is the director of Minotenk, an Oslo think tank dealing with minority issues,

the women are arguing this is a right. They are using Norwegian rights talk to uphold very conservative values. They took this feminist approach and just totally took over the issue. And now fifty to a hundred women are wearing the niqab, young women who were born here. Some of them are in their late teens.

Several young Muslim women in Oslo told me that a women-only Facebook group affiliated with Islam Net has recently banned Shias. According to Alzaghari, by last summer a few women were openly supporting ISIS in the Muslim community, glorifying its fighters as standing up to the enemies of Islam, and trying to get other women involved. “Some of them are selling cupcakes, so we call it ‘cupcake jihad,’” she said.

4.

Generous Betrayal

On the afternoon of July 22, 2011, when the first horrific reports of Breivik’s attacks reached the Norwegian public, many assumed they were carried out by Islamic extremists. When the killer turned out instead to be a “lone-wolf” Norwegian, there was a reluctance to go too far into his motives. “The debate about July 22 has been mostly about psychiatrists, not ideologists,” said Shoaib Sultan, the former secretary general of the Islamic Council of Norway, who is now a researcher at the Norwegian Center Against Racism. “If 7/22 had been done by a Muslim guy, we would never have this prolonged discussion about his mental health.” In 2012, following two separate psychological assessments, Breivik was ruled mentally capable and sentenced to twenty-one years in prison—the maximum allowed under Norwegian law.

Nor has there been much debate about the growing hostility to Muslims in Norway since Breivik’s attack. Partly, this may be the result of the new jihadism that has emerged with the Syrian conflict, a jihadism that is seen as self-evidently objectionable. But some also see the blunt talk about Islam as an effect of former Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg’s call for more dialogue and openness. As the Norwegian social anthropologist Sindre Bangstad writes in a provocative recent book, Anders Breivik and the Rise of Islamophobia, the theory is that, by being brought into the political process, the populist right wing has “impeded the growth of extreme right-wing movements.” Bangstad himself is skeptical of this argument, observing that “populist right-wing rhetoric on Islam and Muslims in Norway…has functioned as an amplifier, rather than merely a channel for anti-immigration and anti-Muslim views and sentiments.”

Far more attention has been devoted to analogous forces playing out in the Muslim community. “Islam Net can be understood in two ways,” Shoaib Sultan told me: “As a dam holding people back from joining something more extreme, by saying ‘people who want real Islam can come to us’; or as a recruiting pool from which extremists like the Prophet’s Umma can pull people. The debate isn’t over.” For all the scrutiny, however, the possibility that Salafist groups may be strengthened by anti-Muslim rhetoric on the right has yet to be addressed.

5.

The Facebook Mujahideen

During nearly a month in Norway, I often found it difficult to reconcile the stories I heard about extremism—whether from the far right or from Islamists—with the congenial surroundings and the exceptionally articulate people I met. I visited a primary school in Oslo that had a population of 60 percent immigrants and 40 percent ethnic Norwegian children; it seemed to be as well if not better integrated than any school in a large American city. At the main campus of Oslo University, I found thoughtful, headscarf-wearing Muslim women especially well represented. One of the rising stars in the Labor Party is Hadia Tajik, a Pakistani Norwegian woman who held her first cabinet post at age twenty-nine and is now, at thirty-one, chair of the Justice Committee in the Norwegian Parliament. Sultan, who is forty-one and also of Muslim Pakistani background, is running for mayor of Oslo.

But these successes seemed to be double-edged. A journalist of Muslim Iraqi background who had lived in Norway for decades, published frequent articles in the Norwegian press, and taught Norwegian to immigrants described to me how the “system” took excellent care of him, but the native population never made him feel he was included in their lives. In turn, several liberal Norwegians complained that Muslim families tended to shun state-funded day care, birthday parties, and swim classes—in the process hindering their kids’ ability to “fit in.”

In a controversial book published shortly after September 11, 2001, the social anthropologist Unni Wikan described the problem of Norway’s treatment of its new minorities as a “generous betrayal”: social benefits and well-intended rhetoric about multiculturalism were serving as stand-ins for more meaningful integration, with the result that an “underclass” of immigrants had been created. In fact, for youth who are otherwise unable to succeed in Norwegian society, the welfare system itself may be facilitating their involvement in jihadist groups. “In a way, things here are too easy,” Alzaghari, the Muslim activist, said. “These guys in the Prophet’s Umma are supported on welfare.”

Early last fall, a few weeks after Ubaydullah Hussain’s interview in VG, I went to see Jonas Gahr Støre, the Labor Party leader, at his office at the Norwegian Parliament. I found him surprisingly candid about the challenges posed by both kinds of extremism to Norwegian democracy. “There are strong similarities between the July 22 attacks and Islamic radicalism,” he said. Referring to Breivik’s plot to behead him and the two other Labor leaders, he added: “It’s part of the same link, spectacular violence linked to mass distribution on the Internet.”

Støre believes that other Norwegians share some of Breivik’s views: “Could it be that this man is alone in what he did, but not in what he thought? We know very clearly that he is not alone in harboring those opinions. We can almost hear it in the political debate.” And yet he strongly resists any curbs on speech. “After the July 22 attacks,” he said, “I think there is wide agreement in this country that one way of dealing with extremism is to shed light on it. Get it out of the dark corners.”

In 2011, shortly before the Breivik attacks, a group of experts convened by the government issued a report on “Welfare and Migration,” which concluded that parts of Norway’s social model were poorly adapted to incoming foreigners. Støre argues the contrary: that Norway with its large size and small population is uniquely positioned to benefit from more immigration and that the state needs to “enlarge the ‘we’”—embrace a more flexible view of Norwegian identity. But he too concedes that some welfare reform may be necessary.

For now, despite fears of new attacks, many Norwegians seem hopeful that the growing divisions can be overcome. For all its earlier rhetoric, the Progress Party has been rather moderate and sensible now that it has to govern with other parties; when I met Solveig Horne, Norway’s minister of children, equality, and social inclusion, who is a Progress Party member, she spoke openly about the problems of discrimination faced by minorities in the Norwegian job market. Meanwhile, amid growing fears about jihadists returning from Syria, officials believe that the flow of Norwegians into the conflict has slowed.

An early turning point may have been in November 2013, when Islam Net invited a well-known American-based Salafist cleric named Sheikh Yasin Khalid to speak in Oslo. In a dramatic sermon, Yasin Khalid made a blistering attack on efforts by jihadist groups to lure young Europeans to Syria. He suggested that those who were fighting lacked a true sense of Islam and called their recruiters a “Facebook Mujahideen.” These men “didn’t make Hajj, yet, but they want to make jihad,” he said. In the months since, Islam Net has distanced itself from the Syrian jihad.

And yet with Breivik has come the ominous knowledge that it takes only one jihadist—or counter-jihadist—to change everything, and that right-wing anti-immigration politics and jihadism are mutually reinforcing. “The relationship between the extremists is a symbiosis,” said Sultan, the Muslim politician and analyst of extremism. “The anti-Muslims actually need Muslim extremists to grow. For these people its vital to have someone like Ubaydullah Hussain, so they can say everyone is like that.”

—February 5, 2015

This Issue

March 5, 2015

Vaccinate or Not?

Our Date with Miranda

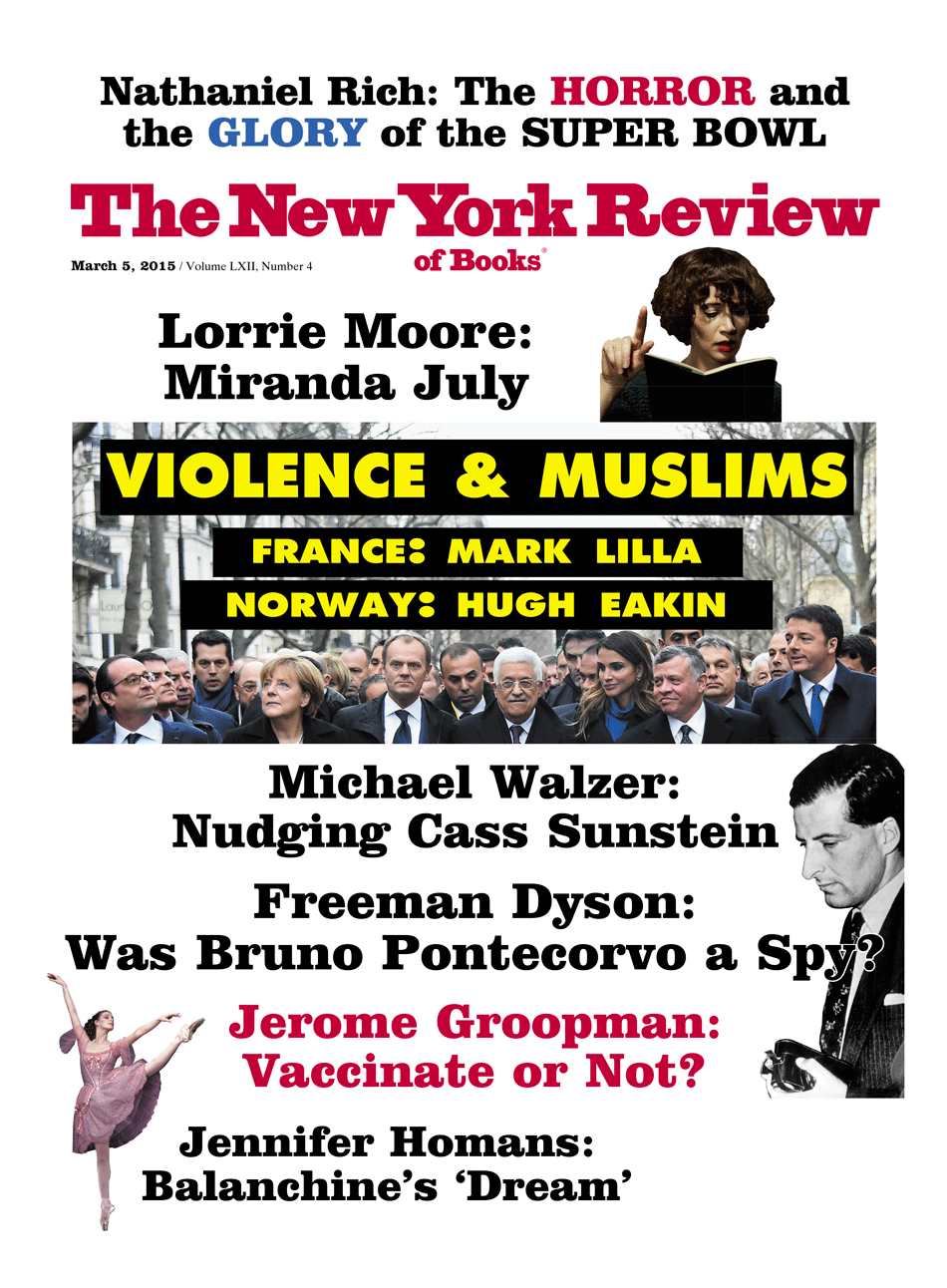

France on Fire