We are uneasy about a story until we know who is telling it.

—Joan Didion, A Book of Common Prayer

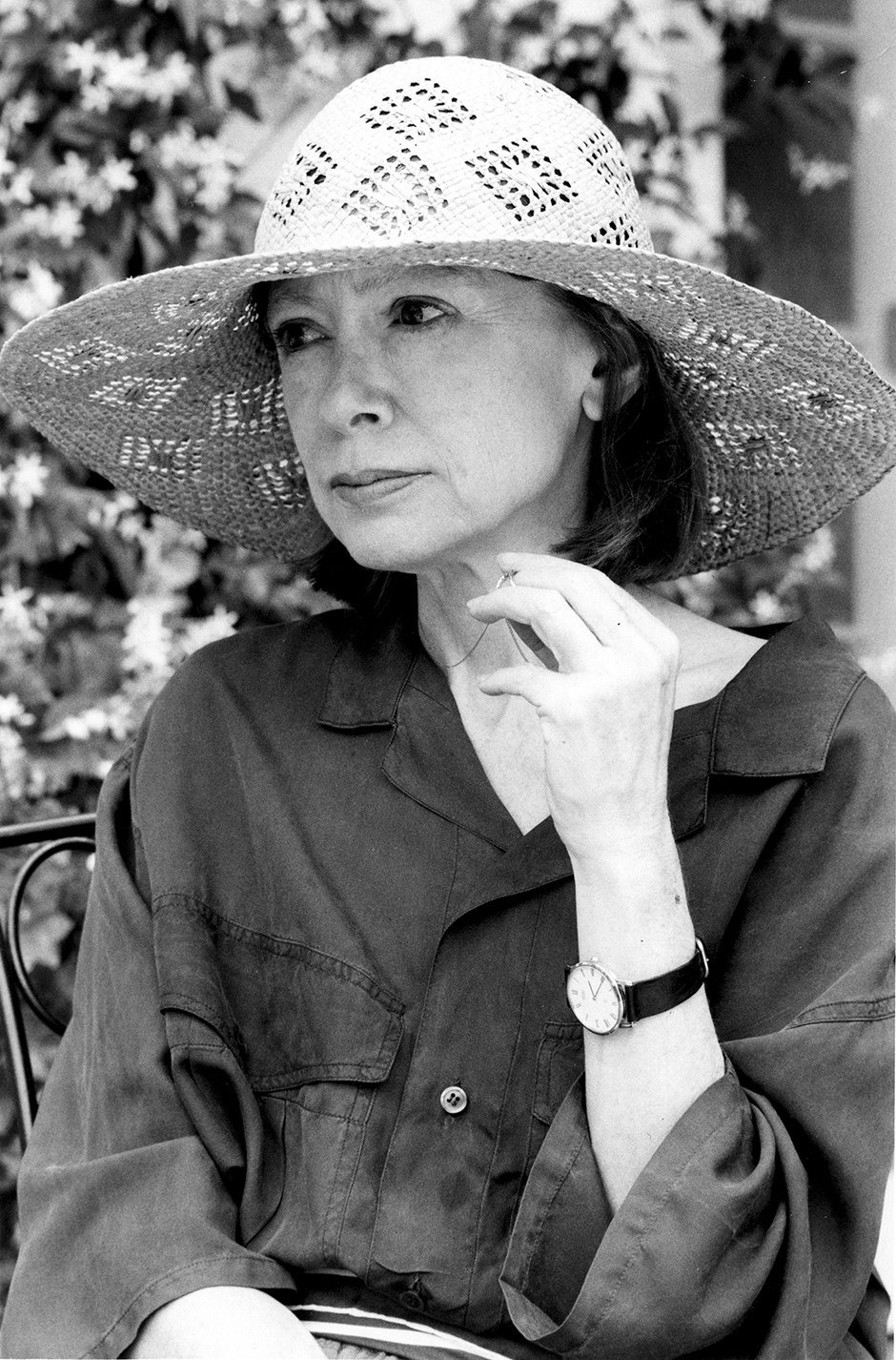

It is rare to find a biographer so temperamentally, intellectually, and even stylistically matched with his subject as Tracy Daugherty, author of well-received biographies of Donald Barthelme and Joseph Heller, is matched with Joan Didion; but it is perhaps less of a surprise if we consider that Daugherty is himself a writer whose work shares with Didion’s classic essays (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968; The White Album, 1979; Where I Was From, 2003) a brooding sense of the valedictory and the elegiac, crushing banality and heartrending loss in American life. To Daugherty, born in 1955, Didion has long been a visionary, “a powerful voice for my generation.” So identifying with his subject, who has suffered personal, familial losses in recent years, as well as a general disillusionment with American politics, the biographer inevitably becomes “an elegist, writing lamentations”; Didion’s memoir Blue Nights (2011), a meditation upon motherhood and aging as well as an elegy for Didion’s daughter Quintana, who died at the age of thirty-nine in 2005, is “not just a harrowing lullaby but our generation’s last love song.”

Chronological in its basic structure, The Last Love Song is not a conventional biography so much as a life of the artist rendered in biographical mode: we pick up crucial facts, so to speak, on the run, as we might in a novel (for instance, in Didion’s debut novel Run River, 1963), in the midst of other bits of information: “By 1934, the year of Didion’s birth, the levees [on the Sacramento River] had significantly reduced flooding.” We learn that Didion’s first, crucial reader was her mother, Eduene, a former Sacramento librarian descended from a Presbyterian minister and his wife who followed the Donner-Reed party west but decided to split from the doomed group in Nevada in 1846. An acquaintance of the family tells Daugherty that the Didions and their extended families “were part of Sacramento’s landed gentry…families who called themselves agriculturalists, farmers, ranchers, progressives, but they were the owners, not the ones who got their hands dirty.” With a novelist’s empathy Daugherty notes:

For all its visibility and influence, the family felt prosaic, muted, sad to Didion, even as a girl. Clerks and administrators: hardly the heroes of old, surviving starvation and blizzards…. A whiff of decadence clung to the gentry.

Many passages in The Last Love Song read with the fluency of fiction, and the particular intimacy of Didion’s fiction, as if by a sort of osmosis the subject has taken over the narrative, as a passenger in a speeding vehicle may take over the wheel. We feel that we are reading about Didion in precisely Didion’s terms:

In considering—and not quite hitting—the real story of Patty Hearst, Didion felt sure the periphery was the key. She looked for an out-of-the-way anecdote, seemingly insignificant, channeling all of California; the pioneer experience in its modern manifestations; the historical imperative; the chain of forces shaping Tania [Hearst’s nom de guerre in the Symbionese Liberation Army]: a verbal image as immediately impactful as the spread legs, the carbine, and the cobra.

She was after this same effect in Play It as It Lays, a “fast novel,” a method of presentation allowing us to see Maria in a flash.

A snake book.

A poetic impulse, surpassing narrative.

Somewhere on the edge of the story.

And:

In the final analysis, Didion’s attraction to conspiracy tales, particularly in the 1980s, has less to do with the intrigues themselves than with her persistent longing for narrative, any narrative, to alleviate the pain of confusion.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live”—and if the story is not readily apparent, we will weave one out of whatever scraps are at hand; we will use our puzzlement as a motivating factor; we will tell our way out of any trap, or goddamn seedy motel.

Introducing the highly charged topic of Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne’s adoption of their daughter Quintana Roo in 1966, Daugherty writes:

In the mid-1960s, the preferred narrative was We chose you.

Positive. Proactive. A comfort to the child.

What the narrative didn’t address—a howling silence no boy or girl failed to perceive—was that if we chose you, someone else chose to make you available to us.

To relinquish you.

Family law.

Though Daugherty is never less than respectful of his subject he cannot resist the biographer’s urge to interpret motives seemingly unacknowledged by the subject, as in a gently condescending film voice-over:

In retrospect, this reference to the severing of family ties [in Didion’s essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”] clearly shows Didion in the Haight worrying about her adopted daughter back [home], the house cased all day by strangers driving unmarked panel trucks. And as in all her subsequent work, whenever she wrote about her daughter, she was also writing about herself.

But is this true? Is this in any way provable? In biography we are tempted to claim, as in life we are tempted to claim, that the plausible may be true; what would seem to be, to be. But in life it is rarely the case that causes and effects are so clear, and the same should hold in the art of biography, which should present possibilities, theories, inferences as tentative, not flatly stated. You have only to examine Didion’s prose before her daughter came into her life to feel that she would very likely have written about Haight-Ashbury residents (adolescents “who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together”) exactly as she did, if she’d never adopted a baby. And it might be said of any writer that when he/she writes about any character, the subject is actually the self.

Advertisement

Years later, in the sobriety of post–September 11 America, here is a portrait of Didion in her “maturity”:

[Her] self-correcting quality, her ability to be ruthlessly self-evaluative and change her mind when she saw she’d been wrong, trumped her contrarian streak. If she had a strong capacity for denial, she had an even stronger will to shuck her illusions once she’d exposed them.

“I think of political writing as in many ways a futile act,” Didion said. But “you are obligated to do things you think are futile. It’s like living. Life ends in death, but you live it, you know.”

As a professor of English and creative writing at Oregon State, Tracy Daugherty is, like his subject, steeped in New Critical theories and stratagems. Both the biographer and his subject distrust direct statement and “abhor abstractions” and both are “wary of interpreting behavior as a clue to character.” Confronted with Didion’s decision not to cooperate with him (though she does not seem to have wished to hamper him), the biographer decides to approach his subject’s life as if its truths do not lie easily on the surface of that life but constitute a text (my term, not Daugherty’s) to be decoded:

When presented with the private correspondence, diaries, journals, or rough drafts of a writer, I remain skeptical of content, attentive instead to presentation. It is the construction of persona, even in private—the fears, curlicues, and desires in any recorded life—that offers insights.

In this approach Daugherty echoes Didion’s acknowledgment of her indebtedness to the English Department at UC-Berkeley, from which she received a BA in 1956: “They taught a form of literary criticism which was based on analyzing texts in a very close way….” And “I still go to the text. Meaning for me is in the grammar…. I learned backwards and forwards close textual analysis.”

For all her insight into political intrigue and the bitter ironies of American life in the late twentieth century, Didion’s essential interest, Daugherty suggests, has always been language: “its inaccuracies and illusions, the way words imply their opposites”; Didion has many times stated her hostility to fashionable and politically correct dogma, as in her defense of the “irreducible ambiguities” of fiction vis-à-vis the “narrow and cracked determinism” of the women’s movement with its “aversion to adult sexual life”:

All one’s actual apprehension of what it is like to be a woman, the irreconcilable difference of it—that sense of living one’s deepest life underwater, that dark involvement with blood and birth and death—could now be declared invalid, unnecessary, one never felt it at all.

In this passage Didion anticipates the sentiment of the anthropologist-narrator who recounts, in a stylized Conradian narrative of detachment and analysis, the story of maternal loss at the core of A Book of Common Prayer:

[Charlotte Douglas] had tried only to rid herself of her dreams, and these dreams seemed to deal only with sexual surrender and infant death, commonplaces of the female obsessional life. We all have the same dreams.

But do we? Feminism challenges this romantic passivity, replacing Freud’s idea of women’s biological destiny with a “destiny” unburdened by gender, like that of men; in her passionately written screed against the very bedrock of feminism, Didion aligns herself with other notable women writers who have scorned the notion of sisterhood. If you have suffered in the “female obsessional life” and if that life has been, for you, in its most profound moments essentially an “underground” life, it will be anathema to be told that others wish to escape this gender-fate. In her denunciation of feminism Didion seems to miss the point: feminism is the politics of human equality, which means economic as well as sexual equality. To deflect the issue onto a matter of language, and the “ambiguities” of language, is perhaps misguided, however esoteric.

Advertisement

In her fiction, which is usually more nuanced than her nonfiction, Didion presents clearly flawed female protagonists like Maria of Play It as It Lays, whose masochism allows her to be swinishly exploited by men, and Charlotte Douglas of A Book of Common Prayer, who is seduced and misused by her Berkeley English instructor yet falls in love with him. Maddeningly, Charlotte is incapable of defining herself except by way of accepting a man’s domination or as a (failed) mother of a pseudo-revolutionary cliché-spouting daughter (in the mode of Patty Hearst) who sets into motion the actions ending in Charlotte’s death. We know that the spoiled daughter, Marin, can only disappoint: “Marin would never bother changing a phrase to suit herself because she perceived the meanings of words only dimly, and without interest.” Of the doomed Charlotte the narrator says, with some exasperation: “I think I have never known anyone who led quite so unexamined a life.”

The most intensely examined female life in Joan Didion’s oeuvre appears to have been her own exhaustively considered interior life; Didion’s most brilliantly created fictional character is the writer’s persona—“Joan Didion.”

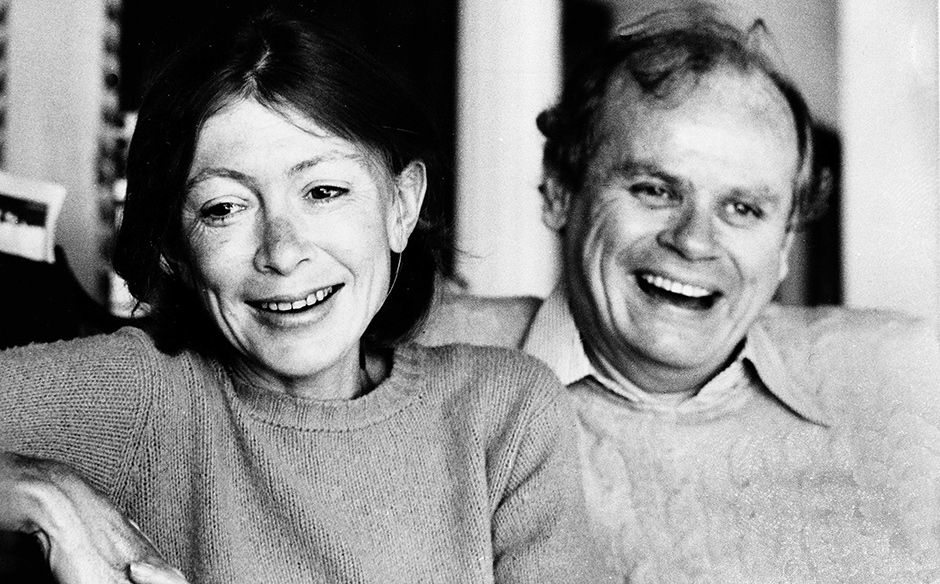

In its most entertaining passages The Last Love Song is something of a joint biography of Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, Didion’s writer-husband of nearly forty years, with whom she collaborated on, among other movies, screenplays for The Panic in Needle Park (1971), Play It as It Lays (1972), and, their most successful film, a remake of A Star Is Born with Barbra Streisand (1976). Author of the novels True Confessions, Dutch Shea, Jr., The Red White and Blue, Nothing Lost, and the memoirs Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season and Harp, Dunne was ebulliently outspoken, the acerbic and sometimes scandalous extrovert to Didion’s “neurotically inarticulate” introvert.

Here is Didion writing with disarming candor of a stay at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu in the aftermath of an earthquake in the Aleutians: “In the absence of a natural disaster we are left again to our own uneasy devices. We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce.” Didion’s confiding tone suggests a private diary entry, but it was very publicly printed in 1969 in Life magazine to be consumed by hundreds of thousands of readers for whom the “confessional” mode was not a commonplace. Not surprisingly, Dunne confides in strangers with startling intimacy as well, in the quasi-autobiographical Vegas (1974) with its memorable, Didion-like opening: “In the summer of my nervous breakdown, I went to live in Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada.”

Daugherty quotes Dunne’s cool observation: “Sometimes, living with [Didion] was like ‘living with [a] piranha.’” Daugherty writes:

Sometimes, at his most depressed, [Dunne] would imagine writing suicide notes, but “whatever minimal impulse I had for suicide was negated by the craft of writing the suicide note. It became a technical problem.” He could not stop revising.

“When are you coming home?” [Didion] asked when she called.

A nuanced, nostalgic, and loving portrait of Dunne emerges decades later in The Year of Magical Thinking, but Dunne’s droll, often raucous voice pervades virtually all of Didion’s prose fiction and gives to certain of her male characters a distinctly comic-aggressive tone in welcome contrast to her repressed, temperamentally inarticulate female characters.

In December 2003 John Gregory Dunne died, of a heart attack, in the couple’s Manhattan apartment as abruptly as Jack Lovett dies of a heart attack at the end of Democracy. As Inez Victor is a stunned witness to her lover’s death so Joan Didion was a witness to her husband’s death. In prose eerily forecasting the opening lines of The Year of Magical Thinking, the narrator of Democracy recounts Lovett’s in a swimming pool at a hotel in Jakarta:

It had been quite sudden.

She had watched him swimming toward the shallow end of the pool.

She had reached down to get him a towel.

She had thought at the exact moment of reaching for the towel about the telephone number he had given her, and wondered who would answer if she called it.

And then she had looked up.

Earlier in the novel, her narrator writes: “You see the shards of the novel I am no longer writing, the island, the family, the situation. I lost patience with it. I lost nerve.”

Of course, Didion’s narrator has not really lost nerve: she has in fact just begun “her” novel. The narrator so intimately addressing us is not Joan Didion and we should not confuse her with the author whose name is on the title page of the book though we have been, in the teasing manner of Philip Roth, invited to confuse the two:

Call me the author.

Let the reader be introduced to Joan Didion, upon whose character and doings much will depend of whatever interest these pages may have, as she sits at her writing table in her own room in her own house on Welbeck Street.

And with an air of weary disdain in The Last Thing He Wanted, she writes:

The persona of “the writer” does not attract me. As a way of being it has its flat sides. Nor am I comfortable around the literary life: its traditional dramatic line (the romance of solitude, of interior struggle, of the lone seeker after truth) came to seem early on a trying conceit. I lost patience somewhat later with the conventions of the craft, with exposition, with transitions, with the development and revelation of “character.”

Didion uses such authorial intrusions to lend credence to her fictional subjects, as she has often used herself in her nonfiction pieces to lend credence to their authenticity; in this, she is unlike her contemporaries John Barth, Robert Coover, Donald Barthelme, and others associated with the postmodernist literary experimentation of the 1970s and 1980s, who call attention by such devices to the fabrication of “fictional subjects”—in fact, their inauthenticity. But Didion is a social realist and a passionate, one might say old-fashioned moralist: she is too much under the spell of the real to wish to debunk it, and she has, unlike some of the postmodernists, exciting and meaningful stories to tell.

Her much-stated anxieties about storytelling—“We tell ourselves stories in order to live…. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience”—seem to spring more from aesthetic considerations than from considerations of truth-telling; the anxieties of Didion’s several fictitious narrators are characteristic of writers seeking something other than conventional forms with which to tell their stories. On the one hand, there is the material (“the island, the family, the situation”), on the other hand the way in which the material will be presented. Ezra Pound set a very high standard with his admonition “Make it new!”—a modernist standard whose significance would not have been lost on any ambitious literary writer coming of age in the 1950s.

Whatever her doubts about the limitations of narrative fiction, Didion seems to have thrown herself into journalism with much enthusiasm, optimism, and unstinting energy—a perfect conjunction of reportorial and memoirist urges. The Last Love Song traces in detail the provenance of Didion’s nonfiction pieces, which secured a reputation for her with the publication of Slouching Towards Bethlehem in 1968; originally published in such diverse journals as The Saturday Evening Post, Vogue, The New York Times Magazine, Holiday, and The American Scholar, the essays were urged into book form by Henry Robbins, an editor at the time at Farrar, Straus and Giroux who became a personal friend of the Dunnes. (After Henry, Didion’s essay collection of 1992, is named for the legendary Robbins, who died of a heart attack, at fifty-one, in 1979.)

It has been Didion’s association with The New York Review of Books, however, that seems to have stimulated what was perhaps the most productive phase of her career. Daugherty notes how “as an editor, Robert Silvers intuitively grasped her literary gifts and untapped potential.” Of Didion, Silvers says:

I just thought she was a marvelous observer of American life…. [She is] by no means predictable, by no means an easily classifiable liberal or conservative, she is interested in whether or not people are morally evasive, smug, manipulative, or cruel—those qualities of moral action are very central to all her political work.

Out of Didion’s meticulously researched journalism for The New York Review would come several of her most important books—Salvador (1983), Miami (1987), After Henry, Political Fictions (2001), and Where I Was From; in all, more than forty pieces by Didion would appear in the Review over a period of forty years. Among these is the corrosively brilliant “Sentimental Journeys” (1991), an investigation into the media reports surrounding the Central Park jogger rape case of April 1989, which resulted in the convictions, on virtually no forensic evidence, of five young black men who’d been coerced into confessing to white NYPD detectives; Didion’s focus is upon the sensational media coverage of the case, the play of “white” and “black” stereotypes “devised to obscure not only the city’s actual tensions of race and class but also…the civic and commercial arrangements that made those tensions irreconcilable.”

Running so counter to public opinion—that is, white public opinion—Didion’s essay aroused much controversy for its determination to expose, with the precision of a skilled anatomist performing an autopsy, how the mainstream media presents to a credulous public “crimes…understood to be news to the extent that they offer…a story, a lesson, a high concept”—in this case, the specter of a city haunted by predatory black gangs intent on violating white women. (In 2002, Didion’s skepticism about the case would be vindicated when the New York State Supreme Court vacated the convictions of the “Central Park Five” after a reexamination of DNA evidence and the confession of a serial rapist named Matias Reyes.)

Political Fictions is a collection of essays analyzing the ways in which the American political process has become “perilously remote from the electorate it was meant to represent”; in this media-driven process even politicians of integrity are obliged to concoct “fables” about themselves. Didion’s tone suggests Swiftian indignation modulated by a wry resignation:

There was to writing about politics a certain Sisyphean aspect…. Even that which seemed to be ineluctably clear would again vanish from collective memory, sink traceless into the stream of collapsing news and comment cycles that had become our national River Lethe.

The Last Love Song is not an “authorized” biography and yet it exhibits few of the negative signs of an “unauthorized” biography: it is brimming with quoted material from Didion, both her writing and her interviews, and with a plethora of conversations with, it seems, virtually everyone who knew her, even at second hand. It is warmly generous, laced with the ironic humor Didion and Dunne famously cultivated. The biographical subject acquires a hologram-like density and her voice is everywhere present.

In his consideration of Didion’s personal life, Daugherty can’t avoid touching upon the vicissitudes of living intimately with the sometimes volatile John Gregory Dunne and with their adopted daughter Quintana Roo, who as a young adolescent, living in California, had already begun exhibiting signs of depression and a penchant for self-medication. (“Just let me be in the ground. Just let me be in the ground and go to sleep”—Didion quotes Quintana in Blue Nights, echoing lines from Democracy uttered by Inez Victor’s unhappy daughter Jessie: “Let me die and get it over with…. Let me be in the ground and go to sleep.”)

Passages dealing with Quintana’s difficult adolescence, her stints in rehab, and her final, protracted illness and death within two years of that of John Gregory Dunne are the most painful passages in The Last Love Song. Of her daughter’s collapse Didion writes in Blue Nights with a disconcerting frankness that manages yet to be oblique:

She was depressed. She was anxious. Because she was depressed and because she was anxious she drank too much. This was called medicating herself. Alcohol has its well-known defects as a medication for depression but no one has ever suggested—ask any doctor—that it is not the most effective anti-anxiety agent yet known.

Didion’s early work may be associated with a particular tone, what might be called a higher coolness (“What makes Iago evil? some people ask. I never ask”), and a predilection for establishing herself as a center of consciousness:

It occurred to me during the summer of 1988, in California and Atlanta and New Orleans, in the course of watching first the California primary and then the Democratic and Republican national conventions, that it had not been by accident that the people with whom I had preferred to spend time in high school had, on the whole, hung out in gas stations.

But overall the range of her writerly interests is considerable: from the chic anomie of Play It As It Lays to the sharp-eyed sociological reportage of Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album; from small gems of self-appraisal (“On Keeping a Notebook,” “On Going Home,” “Goodbye to All That”) to the sustained skittishness of A Book of Common Prayer and Democracy; from the restrained contempt of “In the Realm of the Fisher King” (Reagan’s White House) to the vivid sightings of “Fire Season” (Los Angeles County, 1978); from the powerful evocations of deadly, clandestine politics in Salvador to family autobiography with a title precisely chosen to emphasize the past tense, Where I Was From, and the more recent memoirs of loss, The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights. Who but Joan Didion could frame the stark pessimism of The Last Thing He Wanted—with its incantatory reiteration that deal-making, gun-running (in this case, illegally supplying arms to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua in 1984) is the essential American dream—within a romantic tale of a daughter fulfilling a dying parent’s wish for a “million-dollar score”?

Rare among her contemporaries and, it would seem, against the grain of her own unassertive nature, Didion has forced herself to explore subjects that put her at considerable physical risk, involving travel to the sorts of febrile revolution-prone Central American countries that have figured in her fiction (“Boca Grande,” for instance, of A Book of Common Prayer, the purposefully unnamed island of The Last Thing He Wanted) and a seeming restlessness with staying in one place for long: “If I have to die, I’d rather die up against a wall someplace…. On the case, yes.”