Joshua Cohen’s remarkable Book of Numbers begins by strongly suggesting that we not read the novel with one forefinger lightly skimming the screen of our portable electronic device: “If you’re reading this on a screen, fuck off. I’ll only talk if I’m gripped with both hands.” After this initial salvo, the narrator natters on without providing much in the way of solid introductory information:

I’m writing a memoir, of course—half bio, half autobio, it feels—I’m writing the memoir of a man not me.

It begins in a resort, a suite.

I’m holed up here, blackout shades downed, drowned in loud media, all to keep from having to deal with yet another country outside the window.

If I’d kept the eyemask and earplugs from the jet, I wouldn’t even have to describe this, there’s nothing worse than description: hotel room prose. No, characterization is worse. No, dialogue is…. Anyway this isn’t quite a hotel. It’s a cemetery for people both deceased and on vacation, who still check in daily with work.

Who is telling this story? Where is it taking place? What are we meant to conclude as the narrative voice veers between the impersonal argot of technology and a propulsive confession of misery and neurosis?

Unless you have a taste for ambiguity and frenetic verbosity, for cerebral literary games, and for the sort of fiction in which two of the principal characters have the same name as the author and one of those characters is a writer, you might be tempted to give up. But within a few pages Book of Numbers becomes not only clear, but (at least for a while) pleasurable to read.

Its early chapters feature a succession of dazzling set pieces, among them an orgiastic publication party that spills from a bar in Manhattan’s meatpacking district into the bar’s men’s room and beyond:

All of college was crammed into the stall, Columbia University class of 1992, with a guy whose philosophy essays I used to write, now become iBanker, let’s call him P. Sachs or Philip S., sitting not on the seat but up on the tank, with the copy of my book I’d autographed for him on his lap—“To P.S., with affect(at)tion” rolling a $100 bill, tapping out the lines to dust the dustjacket, offering Cal and Kimi! bumps off the blurbs, offering me.

“Cocaine’s gotten better since the Citigroup merger.”

A knock, a peremptory bouncer’s fist, and the door’s opened to another bar, yet another—but which bars we, despite half of us being journalists, wouldn’t recollect: that dive across the street, diving into the street and lying splayed between the lanes. Straight shots by twos, picklebacks. Well bourbons chasing pabsts. Beating on the jukebox for swallowing our quarters.

Shortly afterward, Cohen manages, in the space of just a few paragraphs, to convey the chaos and horror of September 11:

A firetruck with Jersey plates, wreathed by squadcars, sped, then crept toward the cloud. A man, lips bandaged to match his bowtie, offered a prayer to a parkingmeter. A bleeding woman in a spandex unitard knelt by a hydrant counting out the contents of her pouch, reminding herself of who she was from her swipecard ID. A bullhorn yelled for calm in barrio Cantonese, or Mandarin. The wind of the crossstreets was the tail of a rat, swatting, slapping. Fights over waterbottles. Fights over phones.

Survivors were still staggering, north against traffic but then with traffic too, gridlocked strangers desperate for a bridge, or a river to hiss in, their heads scorched bald into sirens, the stains on their suits the faces of friends. With no shoes or one shoe and some still holding their briefcases. Which had always been just something to hold. A death’s democracy of C-level execs and custodians, blind, deaf, concussed, uniformly tattered in charred skin cut with glass, slit by flitting discs, diskettes, and paper, envelopes seared to feet and hands—they struggled as if to open themselves, to open and read one another before they fell, and the rising tide of a black airborne ocean towed them in.

By now we understand that our narrator is one of the two fictive Joshua Cohens, a writer whose first book, a Holocaust narrative based on his mother’s experience, is published on September 11, 2001. Unable to stop viewing the historic catastrophe and the consequent lack of attention for his book as a personal misfortune (“I was the only NYer not allowed to be sad, once it came out what I was sad about”), Joshua retreats to his apartment, a bleak storage facility in Ridgewood, Queens. He becomes “a legit critic…Mr. Pronunciamento, a taste arbiteur and approviste, dispensing consensus, and expensing it too” while his friend Cal’s volume of reportage from the war in Afghanistan is nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and spends twenty-two galling months on the best-seller list. Finally Joshua gets what appears to be a break. An online site assigns him to interview the other Joshua Cohen, the billionaire tech wizard who invented Tetration, an Internet search engine so widely adopted that, like Google, it has become a verb: to tetrate.

Advertisement

At Tetration’s newly constructed headquarters in Manhattan, the mogul answers Joshua’s questions in curt, dismissive shorthand and with absurd aphorisms: “Confidence is liability packaged as like asset, and asset packaged as like liability.” Before Joshua’s essay can be published, Tetration insists on the right to approve its founder’s quotes; even so, the piece is killed. “Tetration requested nonpublication. They were expecting doublefisted puffycheeked blowjob hagiography.”

Joshua’s career declines precipitously: “I edited the demented terrorism at the Super Bowl screenplay of a former referee living on unspecified disability in Westchester. I turned the halitotic ramblings of a strange shawled cat lady in Glen Cove into a children’s book about a dog detective.” And his personal life is equally dismal: solitude, penury, serious addictions to porn and Xanax, a marriage in the terminal stages of dissolution. So he is understandably excited by the promise of adventure, travel, and lucrative employment when the technocrat who shares his name (but is now to be referred to only as “the Principal”) hires him to ghostwrite a memoir that will tell the Principal’s life story and recount the glorious saga of Tetration’s founding.

In fact Joshua’s work will turn out to involve extensive travel, first to a compound in Palo Alto where he is initiated into the rituals of secrecy and security that will govern every contact with the Principal. His computer is requisitioned and replaced with a new model; his preferences and vices are registered and monitored; he is told that he must pretend to be a genealogist:

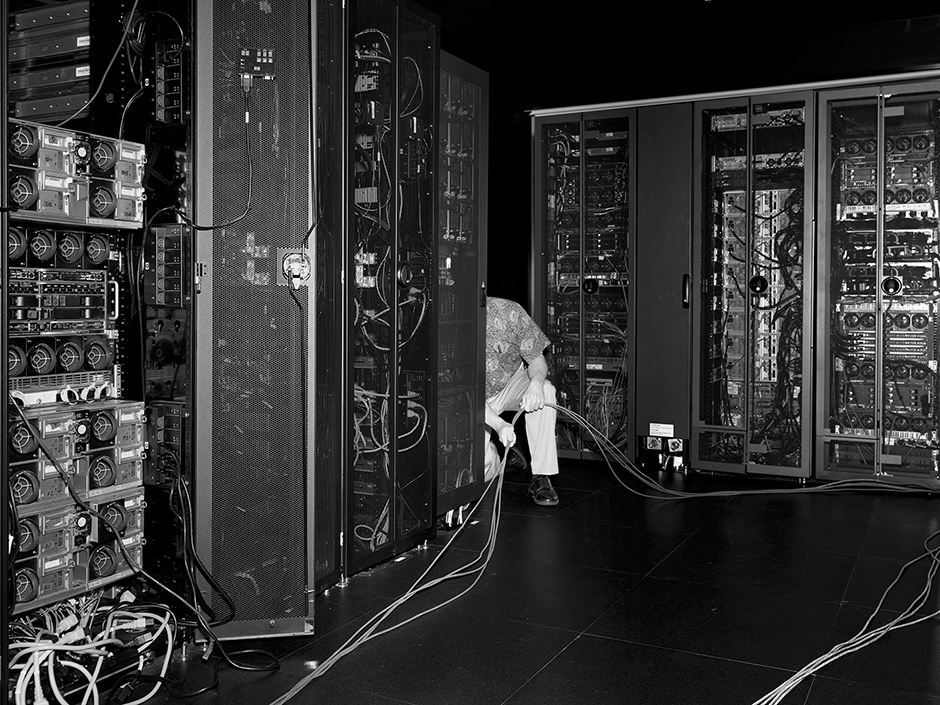

I had no secret, I was no secret, to be Principal’s guest was to have nowhere to hide—not just the laptop but, beyond the panes, the surveillance outside, the tall strong stalks of spyquip planted amid the birch and cedar, the sophisticated growths of recognizant CCTV, efflorescing through my bungalow’s peephole, getting tangled in the eaves.

If all this seems more appropriate for high-level espionage and illegal snooping than for a Silicon Valley corporation, it is. Thanks to the intercession of Thor Ang Balk, a half-Norwegian, half-Swede whose history closely resembles that of Julian Assange, the truth about Tetration’s complicity in government spying will eventually emerge. (In interviews, the real Joshua Cohen has said that he wrote much of this before Edward Snowden’s revelations about NSA surveillance, and that an Internet-savvy friend had advised him that such a scenario was unlikely.)

But before these unfortunate aspects of the search engine’s mission come to light, Joshua is happy enough to exchange his Ridgewood storage facility for flights on private jets to London, Paris, and the Emirates. At luxury hotels, where sheikhs drop by for a visit and gorgeous Slavic women lounge around the pool, Joshua conducts marathon interviews with the Principal, beseeches his friends to e-mail him porn, and reads his soon-to-be-ex-wife Rach’s blog, which mostly consists of complaints about him and their marriage, reports about her career in advertising, and about life with her new boyfriend, an actor. In Abu Dhabi, Joshua saves a Yemeni woman from being beaten by her husband, falls rhapsodically in love with her, and takes her on an expensive shopping spree at the local mall.

Our interest in these characters—and our admiration for Cohen’s energy and wit—carry us through the first hundred pages or so of the second section, in which we read about the Principal’s childhood as an indulged California kid who grows up in “a good neighborhood too überaware of its goodness” and calls his parents M-Unit and D-Unit. And we learn more than anyone could possibly want to know about the birth of Tetration.

We assume that the Principal has hired Joshua to produce something resembling those ghostwritten autobiographies of financial geniuses who make stock market fortunes and save corporate empires from going broke, books that contain snippets of helpful business advice and that one sees stacked in pyramids in airport newsstands. Instead Book of Numbers gives us sections of the Principal’s memoir along with Joshua’s comments and corrections, interspersed with pages of raw transcript purporting to tell us precisely what the Principal said.

Before too long, we may find ourselves doing what Joshua calls “that guiltily-flip-ahead-to-gauge-how-many-pages-are-left-in-the-chapter thing.” For our powers of comprehension—and our patience—are increasingly tested by long sections that compel us not only to witness but to suffer the extent to which the written word has been pauperized and degraded by the technosavant’s belief that the only language that matters is programming language. Nor does it help much when the Principal reveals himself to be one of those egomaniacs who believes that everything he says will be of interest to his listeners.

Advertisement

As a consequence, we get whole pages that, while not entirely without charm, almost defy us to keep reading:

We joined all the religious fora because back then the only pages that existed, smut aside, were about two things, basically: one being the absolute miracle of the very existence of the pages, as like some business celebrating the launch of some placeholder spacewaster site containing only contact information, their address in the real, their phone and fax in the real, and two being the sites of people, predominantly, at this stage, computer scientists or the compscientifically inclined openly indulging their most intimate curs, their most spiritual disclosures, as like experimental diabetes treatment logs….

This is how history begins: with a log of every address online in 1992. 130 was the sum we had by 1993, by which time the countingrooms we were monitoring had projected the sum as like quarterly doubling. 623, approx 4.6% of which were dotcom. 2738, approx 13.5%. There were too many urls to keep track of, so we kept track of sites. There were too many sites to keep track of, so we kept track of host domains that only monitored or made public their numbers of registered sites, not their numbers of sites actually set up and actually functional, and certainly not their names or the urls, the universal resource locators of their individual pages, but what frustrated more than the fact that we could not dbase all the web by ourselves was the fact that none of the models we engineered could ever predict its expansion.

Nor do things improve much when Joshua attempts to convert transcript into memoir:

Diatessaron, hosted at[?]/by[?] the Stanford domain…was a site composed of two pages [EXPLAIN THE DIATESSARON NAME]. One listed [≥400≤600] sites ordered by main url alphabetically within category. The other listed [≥400≤600] the same sites ordered by domain or host alphabetically within category. All listings were suburled, meaning that each site’s pages were listed individually, until that policy had to be abandoned for practical considerations [REMINDER OF EXPLOSIVE GROWTH OF ONLINE], summer 1994.

To make matters even more daunting, long passages—and sometimes entire pages—of the memoir that Joshua is writing for the Principal have been crossed out; strikethroughs bisect every word. That these sentences have become so much more laborious to read helps us to persuade ourselves that we are meant to skip them. Alternately, we may be more likely to persist, if only to find out what Joshua omitted and to speculate about his reasons. So we read on, though the process has become slower and substantially more taxing.

It takes effort to avoid becoming impatient with the Principal’s banal slogans, his neologisms (“splenda” is a term of high praise), and his verbal tics; perhaps unsure about whether to use “as” or “like” in a sentence, he invariably uses both. More often than we might wish, we ask ourselves: Could I really be the only reader who has no idea what this means?

Clearly, these mystifications are intentional, and are part of Cohen’s point: how hard it’s become to make ourselves understood, except by our computers. Reading the novel, we are perpetually reminded of the way in which power confers the right not to care about—not to bother—making sense, and of the technocrat’s pride in having converted “human language,” evolved over centuries, into computer-generated algorithms that can be altered in moments:

Each time each user typed out a word and searched and clicked for what to find, the algy would be educated. We let the algy let its users educate themselves. So it would learn, so its users would be taught. All human language could be determined through this medium, which could not be expressed in any human language, and that was its perfection…. It took approx millions of speakers and thousands of writers over hundreds of years in tens of countries to semantically switch “invest” from its original sense, which was “to confer power on a person through clothing.” Now online it would take something as like one hundred thousand nonacademic and even nonpartisan people in pajamas approx four centiseconds each between checking their stocks to switch it back.

Reviewers have compared Book of Numbers to the fiction of Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace, but the work of William Burroughs also comes to mind. Both writers share a dark malign humor about eroticism and about the grim dystopia that awaits us; neither seems much interested in making things easy for his readers. Indeed the most maddening qualities of Cohen’s book may also be the most admirable: his refusal to make concessions, his insistence on writing what he wants, however trying and potentially vexing.

Near the end of Book of Numbers is a section that not only brings us full circle back to the opening sentence’s insistence that the novel not be read on a screen but also partly explains why Cohen might want us to have slogged through so many pages of crossed-out type:

Computers keep total records, but not of effort, and the pages inked out by their printers leave none. Screens preserve no blemishes or failures. Screens preserve nothing human. Save in the fossiliferous prints left behind by a touch.

But a page—only a page can register the sorrows of the crossings, bad word choice, good word choice gone bad, the gradual dulling of pencil lead….

A notebook is the only place you can write about shit like this and not give a shit, like this. Cheap and tattered, a forgiving space, dizzyingly spiralbound, coiled helical.

The passage confirms what we have intuited throughout the novel: that what we may have mistaken for aggression and provocation has in reality been an expression of grief and loss; and that what Cohen has constructed is an impassioned report on the Miltonic battle between our human souls and the satanic seductions of the Internet. Every garbled paragraph of barely intelligible jargon has been a form of protest against technology’s attempts to undermine our privacy, to subvert the language, and to turn the individual into a processor programmed to convert information into consumer desire. Part of what Cohen appears to value and to want to protect about humanity is its sheer messiness—our vanity, pettiness, lust, selfishness, our political incorrectness, our nostrils filled with “the smell of burning ego”—as opposed to the sterility, the grim predictability, the mechanized functionality of the robot.

To this end, Cohen courageously makes his protagonist a less than exemplary human being: a porn addict who adores a woman with whom he has no common language and who has only minimal sympathy for the wife whose blog post about her miscarriage might be more touching had its tone been less simpering and had she refrained from using the phrase “got pregs.”

Cohen’s novel can be read as a sustained lament for clarity of language, for literature, for the reader who delights in learning new words, for the mind that sees the dictionary as a treasure, and for the “physical” books that were a source of comfort and solace during Joshua’s childhood:

My necessities were books. I read a book at school, another to and from school, yet another at the beach, which was the closest escape from my father’s dying. Though when I walked alone it was far. Though I wasn’t allowed to walk alone when younger—so young that my concern wasn’t the danger to myself but to the books I’d bring, because they weren’t mine, they were everyone’s, entrusted to me in return for exemplary behavior, and if I lost even a single book, or let even its corner get nicked by a jitney, the city would come, the city itself, and lock me up in that grim brick jail that, in every feature, resembled the library.

As long as we maintain—or simply remember—our love for books that can be held in our hands, for pages that can be turned, the hostile incursions of the digital, Cohen suggests, haven’t triumphed completely. We still have an alphabet that can be arranged into meaningful combinations. The problem is how vigorously we are being persuaded that it’s no longer important to understand or care about what those combinations mean.

We finish Book of Numbers at once disturbed and heartened—that is, with some of the same mixed emotions we may feel after watching Citizenfour, Laura Poitras’s documentary about Edward Snowden. It’s probably too late to unplug, to undo the damage, to roll back the system of surveillance that’s been so stealthily put in place. On the other hand, Snowden’s bravery and Cohen’s literary gifts—among them, his quick, tough-minded intelligence, his humor, his nervy refusal to be ingratiating, and his willingness to risk irritating his readers—suggest that something is possible, that something still might be done to safeguard whatever it is that makes us human.