1.

The title of Hanya Yanagihara’s second work of fiction stands in almost comical contrast to its length: at 720 pages, it’s one of the biggest novels to be published this year. To this literal girth there has been added, since the book appeared in March, the metaphorical weight of several prestigious award nominations—among them the Kirkus Prize, which Yanagihara won, the Booker, which she didn’t, and the National Book Award, which will be conferred in mid-November. Both the size of A Little Life and the impact it has had on readers and critics alike—a best seller, the book has received adulatory reviews in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, and other serious venues—reflect, in turn, the largeness of the novel’s themes. These, as one of its four main characters, a group of talented and artistic friends whom Yanagihara traces from college days to their early middle age in and around New York City, puts it, are “sex and food and sleep and friends and money and fame.”

The character who articulates these themes, a black artist on the cusp of success, has one great artistic ambition, which is to “chronicle in pictures the drip of all their lives.” This is Yanagihara’s ambition, too. “Drip,” indeed, suggests why the author thinks her big book deserves its “little” title: eschewing the kind of frenetic plotting that has proved popular recently (as witness, say, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, the 2014 Pulitzer winner), A Little Life presents itself, at least at the beginning, as a modest chronicle of the way that life happens to a small group of people with a bit of history in common—as a catalog of the incremental accumulations that, almost without our noticing it, become the stuff of our lives: the jobs and apartments, the one-night stands and friendships and grudges, the furniture and clothes, lovers and spouses and houses.

In this respect, the book bears a superficial resemblance to a certain kind of “woman’s novel” of an earlier age—Mary McCarthy’s 1963 best seller The Group, say, which similarly traces the trajectories of a group of college friends over a span of time. But the objects of this woman novelist’s scrutiny are men. Bound by friendships first formed at an unnamed northeastern liberal arts college, Yanagihara’s cast is as carefully diversified as the crew in one of those 1940s wartime bomber movies, however twenty-first-century their anxieties may be. There is the black artist, JB, a gay man of Haitian descent who’s been raised by a single mother; Malcolm, a biracial architect who rather comically “comes out” as a straight man and frets guiltily over his parents’ wealth; Willem, a handsome and amiable midwestern actor who stumbles into stardom; and Jude, a brilliant, tormented litigator (he’s also a talented amateur vocalist and patissier) with no identifiable ethnicity and a dark secret that shadows his and his friends’ lives.

As contrived as this setup can feel, it has the makings of an interesting novel about a subject that is too rarely explored in contemporary letters: nonsexual friendship among adult men. In an interview she gave to Kirkus Reviews, Yanagihara described her fascination with male friendship—particularly since, she asserted to the interviewer, men are given “such a small emotional palette to work with.” Although she and her female friends often speak about their emotions together, she told the interviewer, men seemed to be different:

I think they have a very hard time still naming what it is to be scared or vulnerable or afraid, and it’s not just that they can’t talk about it—it’s that they can’t sometimes even identify what they’re feeling…. When I hear sometimes my male friends talking about these manifestations of what, to me, is clearly fear, or clearly shame, they really can’t even express the word itself.1

It’s interesting that Yanagihara’s catalog of emotions includes no positive ones: I shall return to this later.

The novel, then, looks as if it’s going to be a masculine version of The Group: a study of a closed society, its language and rituals and secret codes. It’s a theme in which Yanagihara has shown interest before. In her first book, The People in the Trees (2013), a rather heavy-handed parable of colonial exploitation unpersuasively entwined with a lurid tale of child abuse, the main character, a physician who’s investigating a Micronesian tribe whose members achieve spectacular longevity, is struck “by the smallness of the society, by what it must be like to live a life in which everyone you knew or had ever seen might be counted on your fingers.” The strongest parts of that book reflected the anthropological impulse behind the doctor’s wistful observation: the descriptions of the tribe’s habitat, rituals, and mythologies were imaginative and genuinely engaging, unlike the clankingly symbolic pedophiliac subplot. (The search by Western doctors for the source of the natives’ astonishingly long life spans inevitably invites exploitation and ruin; like the island children whom the doctor later adopts and abuses, the island and its tribal culture are “raped” by white men.)

Advertisement

Yanagihara’s new book would seem, at first glance, to have satisfied her wish for a “tribe” she could devote an entire novel to. Its focus is on a tiny group circumscribed to the point of being hermetic: A Little Life never strays from its four principals, and, as other critics have noted, the novel provides so little historical, cultural, or political detail that it’s often difficult to say precisely when the characters’ intense emotional dramas take place.

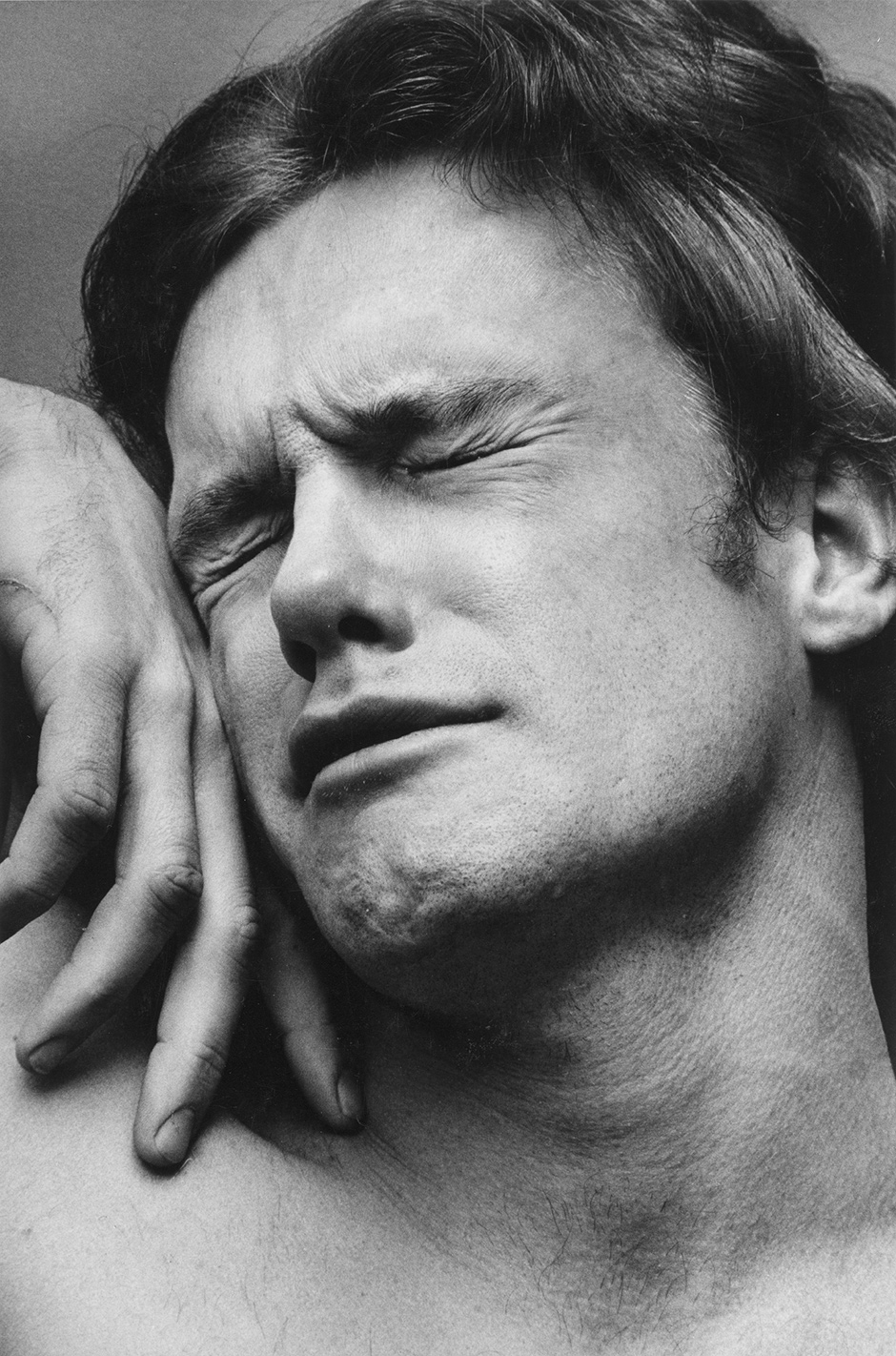

© 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC/Pace-MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Peter Hujar: Orgasmic Man, 1969; from Peter Hujar: Love & Lust, published last year by Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. A new exhibition, ‘Peter Hujar: 21 Pictures,’ will be on view at the gallery, January 7–March 5, 2016.

Yet A Little Life, like its predecessor, gets hopelessly sidetracked by a secondary narrative—one in which, strikingly, homosexual pedophilia is once again the salient element. For Jude, we learn, was serially abused as a child and young adult by the priests and counselors who raised him. This is the dark secret that explains his tormented present: self-cutting and masochistic relationships and, eventually, suicide. (The latter plot point isn’t anything the intelligent reader won’t have guessed after fifty pages.) Yanagihara’s real subject, it turns out, is abjection. What begins as a novel that looks like it’s going to be a bit retro—a cross between Mary McCarthy and a Stendhalian tale of young talent triumphing in a great metropolis—soon reveals itself as a very twenty-first-century tale indeed: abuse, victimization, self-loathing.

This sleight-of-hand is slyly hinted at in the book’s striking cover image, a photograph by the late Peter Hujar of a man grimacing in what appears to be agony. The joke, of which Yanagihara and her publishers were aware, is that the portrait belongs to a series of images that Hujar, who was gay, made of men in the throes of orgasm. In the case of Yanagihara’s novel, however, the “real” feeling—not only what the book is about but, I suspect, what its admirers crave—is pain rather than pleasure.

2.

This is a shame, because Yanagihara is good at providing the pleasures that go with a certain kind of fictional “anthropology.” The accounts of her characters’ early days in New York and their gradual rises to success and celebrity are tangy with vivid aperçus: “There were times when the pressure to achieve happiness felt almost oppressive.” “New York was populated by the ambitious. It was often the only thing that everyone here had in common.”

By far the most fully achieved of the four characters is the actor, Willem, whose rise from actor-waiter to Hollywood stardom, punctuated by flashbacks to his rural childhood (a touchingly described relationship with a crippled brother suggests why he’s so good at both the empathy and self-effacement necessary to his work), is the most persuasive narrative trajectory in the book. A passage about two thirds into the novel in which he realizes he’s “famous” demonstrates Yanagihara’s considerable strengths at evoking a particular milieu—clever, creative downtown types who socialize with one another perhaps too much—and that particular stage of success in which one emerges from the local into the greater world:

There had been a day, about a month after he turned thirty-eight, when Willem realized he was famous. Initially, this had fazed him less than he would have imagined, in part because he had always considered himself sort of famous—he and JB, that is. He’d be out downtown with someone, Jude or someone else, and somebody would come over to say hello to Jude, and Jude would introduce him: “Aaron, do you know Willem?” And Aaron would say, “Of course, Willem Ragnarsson. Everyone knows Willem,” but it wouldn’t be because of his work—it would be because Aaron’s former roommate’s sister had dated him at Yale, or he had two years ago done a reading for Aaron’s friend’s brother’s friend who was a playwright, or because Aaron, who was an artist, had once been in a group show with JB and Asian Henry Young, and he’d met Willem at the after-party. New York City, for much of his adulthood, had simply been an extension of college…the entire infrastructure of which sometimes seemed to have been lifted out of Boston and plunked down within a few blocks’ radius in lower Manhattan and outer Brooklyn.

But now, Willem realizes, the release of a certain film “had created a certain moment that even he recognized would transform his career.” When he gets up from his table at a restaurant to go to the men’s room, he notices “something different about the quality of [the other diners’] attention, its intensity and hush….” This is just right.

Advertisement

It’s telling that Yanagihara’s greatest success is a secondary character: here again, it’s as if she doesn’t know her own strengths. For as A Little Life progresses, the author seems to lose interest in everyone but the tragic victim, Jude. Malcolm, in particular, is never more than a cipher, all too obviously present to fill the biracial slot; and after a brief episode in which JB’s struggle with drug addiction is very effectively chronicled, that character too fades away, reappearing occasionally as the years pass, the grand gay artist with a younger boyfriend on his arm. Overshadowing them all are the dark hints about Jude’s past that accumulate ominously—and coyly. “Traditionally, men—adult men, which he didn’t yet consider himself among—had been interested in him for one reason, and so he had learned to be frightened of them.”

The awkwardness of “which he didn’t yet consider himself among” is, I should say, pervasive. The writing in this book is often atrocious, oscillating between the incoherently ungrammatical—“his mother…had earned her doctorate in education, teaching all the while at the public school near their house that she had deemed JB better than”—and painfully strained attempts at “lyrical” effects: “His silence, so black and total that it was almost gaseous…” You wonder why the former, at least, wasn’t edited out—and why the striking weakness of the prose has gone unremarked by critics and prize juries.

Inasmuch as there’s a structure here, it’s that of a striptease: gradually, in a series of flashbacks, the secrets about Jude’s past are uncovered until at last we get to witness the pivotal moment of abuse, a scene in which one of his many sexual tormentors, a sadistic doctor, deliberately runs him over, leaving him as much a physical cripple as an emotional one. But the wounds inflicted on Jude by the pedophile priests in the orphanage where he grew up, by the truckers and drifters to whom he is pimped out by the priest he runs away with, by the counselors and the young inmates at the youth facility where he ends up after the wicked priest is apprehended, by the evil doctor in whose torture chamber he ends up after escaping from the unhappy youth facility, are nothing compared to those inflicted by Yanagihara herself. As the foregoing catalog suggests, Jude might better have been called “Job,” abandoned by his cruel creator. (Was there not one priest who noticed something, who wanted to help? Not one counselor?)

The sufferings recalled in the flashbacks are echoed in the endless array of humiliations the character is forced to endure in the present-day narrative: the accounts of these form the backbone of the novel. His lameness is mocked by JB—a particularly unbelievable plot point—with whom he subsequently breaks; he compulsively cuts himself with razor blades, an addiction that lands him in the hospital more than once; he rejects the loving attentions of a kindly law professor who adopts him; he takes up with a sadistic male lover who beats him repeatedly and throws him and his wheelchair down a flight of stairs; his leg wounds, in time, get to the point where the limbs have to be amputated. And when Yanagihara seems to grant her protagonist a reprieve by giving him at last a loving partner—late in the novel Willem conveniently emends his sexuality and falls in love with his friend—it’s merely so that she can crush him by killing Willem in a car crash, the tragedy that eventually leads him to take his own life.

You suspect that Yanagihara wanted Jude to be one of those doomed golden children around whose disintegrations certain beloved novels revolve—Sebastian Flyte, say, in Brideshead Revisited. But the problem with Jude is that, from the start, he’s a pill: you never care enough about him to get emotionally involved in the first place, let alone affected by his demise. Sometimes I wondered whether even Yanagihara liked him. There is something punitive in the contrived and unredeemed quality of Jude’s endless sufferings; it sometimes feels as if the author is working off a private emotion of her own.

Yanagihara must have known that the sheer quantity of degradation in her story was likely to alienate readers: “This is just too hard for anybody to take,” her editor at Doubleday told her, according to the Kirkus interview, advice she was apparently proud not to take. It’s interesting to speculate why she persisted. In The People in the Trees, the doctor studying the island culture recalls wishing as a child that he’d had a more traumatic childhood—one in which, indeed, the presence of a crippled brother might bring the family together. “How I yearned for such motivation!” he cries to himself as he recalls his early years. As Yanagihara recognizes in this passage, there is a deep and unadult sentimentality lurking behind that yearning; and yet she herself falls victim to it. In the end, her novel is little more than a machine designed to produce negative emotions for the reader to wallow in—unsurprisingly, the very emotions that, in her Kirkus Reviews interview, she listed as the ones she was interested in, the ones she felt men were incapable of expressing: fear, shame, vulnerability. Both the tediousness of A Little Life and, you imagine, the guilty pleasures it holds for some readers are those of a teenaged rap session, that adolescent social ritual par excellence, in which the same crises and hurts are constantly rehearsed.

We know, alas, that the victims of abuse often end up unhappily imprisoned in cycles of (self-) abuse. But to keep showing this unhappy dynamic at work is not the same as creating a meaningful narrative about it. Yanagihara’s book sometimes feels less like a novel than like a seven-hundred-page-long pamphlet.

3.

Interestingly, it is because of, rather than despite, this failing that A Little Life has struck a nerve among critics and readers. Jon Michaud, in The New Yorker, praised its “subversive” treatment of abuse and suffering, which, he asserts, lies in the book’s refusal to offer “any possibility of redemption and deliverance.”2 Michaud singled out for notice a passage that describes Jude’s love of pure mathematics, in which discipline he pursues a master’s degree at one point—another in the list of his improbable accomplishments—and which, Michaud interestingly observes, takes the place of religion in Jude’s unredeemable world:

Not everyone liked the axiom of equality…but he had always appreciated how elusive it was, how the beauty of the equation itself would always be frustrated by the attempts to prove it. It was the kind of axiom that could drive you mad, that could consume you, that could easily become an entire life.

(The citation allows him to conclude his review by declaring that “Yanagihara’s novel can also drive you mad, consume you….”) Michaud’s is a kind of metacritique: the novel is to be admired not for what it does, but for what it doesn’t do, for the way it bleakly defies conventional—and, by implication, sentimental—expectations of closure. But all “closure” isn’t necessarily mawkish: it’s what gives stories aesthetic and ethical significance. The passage that struck me as significant, by contrast, was one in which the nice law professor expounds one day in class on the difference between “what is fair and what is just, and, as important, between what is fair and what is necessary.” For a novel in the realistic tradition to be effective, it must obey some kind of aesthetic necessity—not least, that of even a faint verisimilitude. The abuse that Yanagihara heaps on her protagonist is neither just from a human point of view nor necessary from an artistic one.

In a related vein, Garth Greenwell in The Atlantic praised A Little Life as “the great gay novel” not because of any traditionally gay subject matter—Greenwell acknowledges that almost none of the characters or love affairs in the book are recognizably gay; it’s noteworthy that when Willem discusses his affair with Jude, he declares that “I’m not in a relationship with a man…I’m in a relationship with Jude,” a statement that in an earlier era would have been tagged as “denial”—but because of its technical or stylistic gestures. Yanagihara’s book is, in fact, curiously reticent about the accoutrements of erotic life that many if not most gay men are familiar with, for better or worse—the pleasures of sex, the anxieties of HIV (which is barely mentioned), the omnipresence of Grindr and porn, of freewheeling erotic energy expressed in any number of ways and available on any numbers of platforms. (When Jude tries to spice up his and Willem’s sex life and orders three “manuals,” some readers might wonder not in what era but on what planet he’s supposed to be living.) But for Greenwell, A Little Life is distinguished by the way it

engages with aesthetic modes long coded as queer: melodrama, sentimental fiction, grand opera….By violating the canons of current literary taste, by embracing melodrama and exaggeration and sentiment, it can access emotional truths denied more modest means of expression.3

Greenwell cites as examples the “elaborate metaphor” to which Yanagihara is given—as, for instance, in the phrase “the snake- and centipede-squirming muck of Jude’s past.”

But not everything that’s excessive or exaggerated is, ipso facto, “operatic.” The mad hyperbole you find in grand opera gives great pleasure, not least because the over-the-top emotions come in beautiful packages; the excess is exalting, not depressing. It is hard to see where the compensatory beauties of A Little Life reside. Yanagihara’s language, as I’ve mentioned, is strained and ungainly rather than artfully baroque: as for melodrama, there isn’t even drama here, let alone anything more heightened—the structure of her story is not the satisfying arc we associate with drama, one in whose shapeliness meaning is implied, but a monotonous series of assaults. It’s hard to see what’s so “gay” or “queer” in this dreariness.

There is an odd sentimentality lurking behind accolades like Greenwell’s. You wonder whether a novel written by a straight white man, one in which urban gay culture is at best sketchily described, in which male homosexuality is for the second time in that author’s work deeply entwined with pedophiliac abuse, in which the only traditional male–male relationship is relegated to a tertiary and semicomic stratum of the narrative, would be celebrated as “the great gay novel” and nominated for the Lambda Literary Award. If anything, you could argue that this female writer’s vision of male bonding revives a pre-Stonewall plot type in which gay characters are desexed, miserable, and eventually punished for finding happiness—a story that looks less like the expression of “queer” aesthetics than like the projection of a regressive and repressive cultural fantasy from the middle of the last century.

It may be that the literary columns of the better general interest magazines are the wrong place to be looking for explanations of why this maudlin work has struck a nerve among readers and critics both. Recently, a colleague of mine at Bard College—one of the models, according to Newsweek, for the unnamed school that the four main characters in A Little Life attended4—drew my attention to an article from Psychology Today about a phenomenon that has been bemusing us and other professors we know: what the article’s author refers to as “declining student resilience.” A symptom of this phenomenon, which has also been the subject of essays in The Chronicle of Higher Education and elsewhere, is the striking increase in recent years in student requests for counseling in connection with the “problems of everyday life.” The author cites, among other cases, those of a student “who felt traumatized because her roommate had called her a ‘bitch’ and two students who had sought counseling because they’d seen a mouse in their off-campus apartment.”5

As comical as those particular instances may be, they remind you that many readers today have reached adulthood in educational institutions where a generalized sense of helplessness and acute anxiety have become the norm; places where, indeed, young people are increasingly encouraged to see themselves not as agents in life but as potential victims: of their dates, their roommates, their professors, of institutions and history in general. In a culture where victimhood has become a claim to status, how could Yanagihara’s book—with its unending parade of aesthetically gratuitous scenes of punitive and humiliating violence—not provide a kind of comfort? To such readers, the ugliness of this author’s subject must bring a kind of pleasure, confirming their preexisting view of the world as a site of victimization and little else.

This is a very “little” view of life. Like Jude and his abusive lover, this book and its champions seem “bound to each other by their mutual disgust and discomfort”; like the image on its cover, Yanagihara’s novel has duped many into confusing anguish and ecstasy, pleasure and pain.

This Issue

December 3, 2015

How She Wants to Modify Muslims

A Hemingway Surprise

-

1

“Hanya Yanagihara, Author of A Little Life, interviewed by Claiborne Smith,” March 16, 2015. ↩

-

2

“The Subversive Brilliance of A Little Life,” April 28, 2015. ↩

-

3

“A Little Life: The Great Gay Novel Might Be Here,” The Atlantic, May 31, 2015. ↩

-

4

Alexander Nazaryan, “Author Hanya Yanagihara’s Not-So-Little Life,” Newsweek, March 19, 2015. ↩

-

5

Peter Gray, “Declining Student Resilience: A Serious Problem for Colleges,” Psychology Today, September 22, 2015. ↩