1.

As the concentration of wealth in America has grown, so has the scale of philanthropy. Today, that activity is one of the principal ways in which the superrich not only “give back” but also exert influence, yet it has not received the attention it deserves. As I have previously tried to show, digital technology offers journalists new ways to cover the world of money and power in America,1 and that’s especially true when it comes to philanthropy.

Over the last fifteen years, the number of foundations with a billion dollars or more in assets has doubled, to more than eighty. A significant portion of that money goes to such traditional causes as universities, museums, hospitals, and local charities. Needless to say, such munificence does much good. The philanthropic sector in the United States is far more dynamic than it is in, say, Europe, due in part to the tax deductions allowed under US law for charitable giving. Unlike in Europe, where cultural institutions depend largely on state support, here they rely mainly on private donors.

The tax write-offs for such contributions, however, mean that this giving is subsidized by US taxpayers. Every year, an estimated $40 billion is diverted from the public treasury through charitable donations. That makes accountability for them all the more pressing. So does the fact that many of today’s philanthropists are more activist than those in the past. A number are current or former hedge fund managers, private equity executives, and tech entrepreneurs who, having made their fortunes on Wall Street or in Silicon Valley, are now seeking to apply their know-how to social problems. Rather than simply write checks for existing institutions, these “philanthrocapitalists,” as they are often called, aggressively seek to shape their operations.

When donors approach a nonprofit, “they’re more likely to say not ‘How can I help you?’ but ‘Here’s my agenda,’” Nicholas Lemann, the former dean of the Columbia School of Journalism, told me. Mainstream news organizations haven’t caught on to this new activism, he said, adding that most of them are into covering “the ‘giving pledge,’” by which the rich commit to giving away at least half their wealth in their lifetime. David Callahan, the founder and editor of Inside Philanthropy, a website that tracks this world, says that “philanthropy is having as much influence as campaign contributions, but campaign contributions get all the attention. The imbalance is stunning to me.”

Callahan, the author of Fortunes of Change: The Rise of the Liberal Rich and the Remaking of America (2010), created Inside Philanthropy in 2013 to help fill this gap. (The Chronicle of Philanthropy is another valuable resource.) The site offers a rich storehouse of information about the causes to which the wealthy give. An entry on Robert Mercer, for instance, notes that he is the co-CEO of Renaissance Technologies (a hedge fund) and a leading contributor to Super PACs, and that his family foundation backs a sprawling array of conservative institutions, including the Media Research Center, which scans the media for liberal bias; the George W. Bush Foundation, which supports the Bush library and museum; and the Heartland Institute, a leading promoter of climate-change denial. The Inside Philanthropy page on eBay billionaire Jeff Skoll notes that his foundation is a leading funder of social entrepreneurs, who seek to apply to social problems techniques borrowed from the business world.

As Callahan notes on Inside Philanthropy, social entrepreneurship—offering microfinance, setting up farmer cooperatives, creating programs for disadvantaged youth—has become a favorite cause of the wealthy, yet its effectiveness has gone largely unexamined. The site has also addressed such subjects as “Why Wall Streeters Love the Manhattan Institute” and “Which Washington Think Tank Do Billionaires Love the Most?” (the American Enterprise Institute).

Inside Philanthropy shows how digital technology can be used to track the new philanthropy. The information offered on the site is all the more impressive given its slender resources. Relying entirely on subscribers, Inside Philanthropy has a modest budget and a staff consisting largely of freelancers. That, unfortunately, limits the amount of digging it can do. The site does not generally undertake extended investigations into how donors have amassed their wealth, or the impact their philanthropy has had, or the sometimes hidden goals of their giving.

The importance of such questions can be seen in, for example, the work of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. According to its website, it concentrates on a handful of subjects, including education, criminal justice, “research integrity,” “evidence-based policy and innovation,” and “sustainable public finance.” On that last matter, the foundation says that it

works to promote fiscal sustainability and the effective oversight of public funds. We are funding efforts to help governments evaluate the impact of tax policies and design public pension systems that are affordable, sustainable, and secure.

All of which sounds quite laudable. A little probing, however, shows that John Arnold for years worked at Enron, trading in natural gas derivatives. In 2001, he reportedly helped earn the company three quarters of a billion dollars, for which he received an $8 million bonus. When Enron collapsed, Arnold set up a hedge fund in Houston that specialized in natural gas trading. Ten years later, he was worth about $3 billion. In 2012, he retired from the fund and set up his foundation. Since then, Arnold has led a campaign to cut public employees’ retirement benefits, making large contributions to politicians, Super PACs, ballot initiative efforts, and think tanks.

Advertisement

As part of that campaign, the Arnold Foundation gave $3.5 million to WNET, the public television station in New York, to support production of a two-year news series called The Pension Peril, to be shown on PBS. The foundation’s involvement was not explicitly disclosed. In a February 2014 article for Pando, an online magazine covering Silicon Valley, David Sirota revealed Arnold’s involvement and noted that the show (which had already begun airing) echoed many of the same pension-cutting themes that he was promoting in state legislatures. Amid growing protests, PBS decided to return the grant and suspend the series, citing internal rules that deem the existence of a clear connection between the interests of a proposed funder and the subject matter of a program unacceptable. Sirota’s article illustrates the type of scrutiny that a website on money, power, and influence could regularly provide.

On Inside Philanthropy, David Callahan noted that the Arnold/PBS case is hardly unique. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation—a strong backer of the Affordable Care Act—gave NPR $5.6 million to report on health care between 2008 and 2011, and the Ford Foundation, which is committed to fighting economic inequality, gave $1 million to public radio’s Marketplace to report on that subject. “Nearly all funders have some kind of ideology and agenda,” Callahan observed. “And whatever media grantees say about their editorial independence, all nonprofits are wary of biting the hands that feed them.” He’s right. Keeping regular track of the growing efforts by foundations and philanthropists, both conservative and liberal, to shape the news would be one of the missions of a website devoted to covering America’s privileged class.2

After Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan announced their plan to donate nearly all of their Facebook stock to charitable causes, the initial laudatory coverage was followed by a series of stories that raised many important questions about their decision, including its implications for avoiding taxes, the large sums it would potentially cost the US government, and the huge amount of power it would place in the hands of two people. As John Cassidy observed in The New Yorker, “The more money billionaires give to their charitable foundations, which in most cases remain under their personal control, the more influence they will accumulate.” Such influence makes regular scrutiny of these kinds of investments all the more urgent.

2.

As a number of the above examples suggest, much of today’s philanthropy is aimed at “intellectual capture”—at winning the public over to a particular ideology or viewpoint. In addition to foundations, the ultrarich are working through advocacy groups, research institutes, paid spokesmen, and—perhaps most significant of all—think tanks. These once-staid organizations have become pivotal battlegrounds in the war of ideas, and moneyed interests are increasingly trying to shape their research—a good subject for a new website. As The Washington Post reported in 2014, for instance, the Brookings Institution, long known for its “impeccable research,” has in recent years placed more and more emphasis on expansion and fund-raising, “giving scholars a bigger role in seeking money from donors and giving donors a voice in Brookings’s research agenda.” In one example, Brookings in November 2012 was visited by a lawyer representing Peter B. Lewis, the billionaire insurance executive who toward the end of his life embraced the cause of legalizing marijuana. Before the visit, the think tank had done little work on the issue, but soon after, the Post reported, it “emerged as a hub of research” supporting legalization, with prominent scholars offering at least twenty seminars, papers, or Op-Ed pieces. Before his death in 2013, Lewis donated $500,000 to Brookings, and two of the scholars involved said they knew he was their benefactor.

Think tanks are also being targeted by foreign governments eager to shape their research to reflect their national interests. As The New York Times reported in 2014, these contributions have “set off troubling questions about intellectual freedom,” with some scholars saying that they “have been pressured to reach conclusions friendly to the government financing the research.” Norway for example committed at least $24 million over four years to an array of Washington think tanks, transforming them “into a powerful but largely hidden arm of the Norway Foreign Affairs Ministry.”

Advertisement

As both these articles suggested, there’s a new ecosystem of lobbying in Washington, with traditional forms of arm-twisting complemented by multipronged campaigns that use surrogates to create the impression of broad support for a company’s or a government’s positions. Given the importance of these new forms of influence-peddling, the articles in the Post and Times cried out for continued follow-up.

The type of website I have in mind would provide it. In the process, it could compile a registry of corporate spokesmen, front groups, researchers for hire, and “astroturf” organizations—ostensibly independent groups that are created by industries and trade groups to advance their interests. Accessing this registry, readers would be able to learn that, for example, Broadband for America, which bills itself as a coalition of consumer advocates and content providers and which opposes net neutrality, is partly funded by the cable industry, and that Energy in Depth, which calls itself a “research, education and public outreach campaign,” is actually an arm of the petroleum industry.

It’s not just conservatives and corporations that are seeking intellectual capture. The Democracy Alliance was founded in 2005 by a group of liberals looking to counter the tide of corporate money into think tanks and advocacy groups. As Kenneth Vogel has reported in Politico, the alliance has compiled a roster of a hundred or so wealthy individuals committed to giving at least $200,000 annually to twenty-one endorsed institutions, among them the Center for American Progress, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, and Media Matters for America. Major donors include George Soros; Rob McKay, the heir to the Taco Bell fortune; Tom Steyer, the former hedge fund manager turned environmental activist; and Houston trial lawyers Amber and Steve Mostyn.

How much each donor gives and to what is not known, however, for the Democracy Alliance is highly secretive, with a website that seems opaque by design. This has fostered a belief on the right that the alliance is at the heart of a vast liberal conspiracy. Leaving aside such hyperbole, the organization seems ripe for examination by an online journalistic website about the superrich.

Such a site would also track the flow of money into universities—another front in the ideological contest that’s underway. The 2010 documentary Inside Job showed how some economic professors, including Columbia’s Glenn Hubbard and Frederic Mishkin, expressed views about the economy without revealing that they’d received income from interested parties. The film set off a vigorous debate at Columbia, which led its business school to adopt new guidelines requiring professors to disclose all outside activities that create possible conflicts of interest. But the influence of big money on campus extends far beyond disclosure forms, with banks, corporations, and entrepreneurs setting up chairs and institutes that apparently are intended to promote capitalism and free enterprise.

In 2009, for instance, the billionaire hedge fund manager John Paulson gave New York University $20 million to create both an Alan Greenspan Chair in Economics and a John A. Paulson Professor of Finance and Alternative Investments. In 2010, the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, which is dedicated to reducing government spending and the national debt, gave a three-year $2.45 million grant to Columbia University’s Teachers College to develop a curriculum “about the fiscal challenges that face the nation,” to be distributed free to every high school in the country. The philanthropic arm of BB&T, a financial services company in North Carolina, has given millions to more than sixty colleges and universities to examine the “moral foundations of capitalism” and promote the works of Ayn Rand. What has been the impact of these donations? How much control, if any, do the donors have over what’s taught? The type of website I’m proposing would seek to answer such questions.

It would also try to show the growing influence of university boards of trustees. These are increasingly made up of corporate figures who, in addition to raising large sums for their institutions, are playing an ever-larger part in their management. A good example is New York University and the furor that erupted over its plan to expand its campus in Greenwich Village and beyond. Officially called NYU 2031, the document became known as the “Sexton Plan,” after the university’s president, John Sexton. Sexton bore much of the faculty’s ire over the plan and the undemocratic way in which they felt it was adopted—all of which received abundant press attention. Less heed was paid to the real center of power at NYU—its board. Of its more than sixty trustees, all but a few come from the worlds of finance, real estate, law, construction, and marketing.

Even within the board, one figure was dominant: Martin Lipton. A prominent corporate lawyer, Lipton served as the board’s chairman from 1998 until his retirement this past October. As Geraldine Fabrikant reported in a 2014 profile in the Times (which was buried deep inside a special education supplement), Lipton was the university’s “power broker,” running the board “with an iron hand,” as several board members told her. More than a decade earlier, he had handpicked Sexton to be president “without any systematic search process.”

More recently, Lipton was deeply involved in the university’s expansion plans. He also sat on the committee to select his own replacement as chair, and (as William Cohan recounted in the Times) played a crucial part in steering the board toward the candidate it eventually settled on—William Berkley, the billionaire chairman of an insurance holding company in Greenwich, Connecticut, and the chairman of a charter school company. To be fair, NYU during Lipton’s reign raised nearly $6 billion, and the man recently chosen as Sexton’s successor, Andrew Hamilton, is a respected Oxford don (and a renowned chemist). But the selection of Berkeley as Lipton’s replacement, together with the continued presence of so many moguls on NYU’s board, suggests that big money will continue to have an outsized influence at the school. Just what form might that influence take? A website devoted to chronicling the activities of the one percent would attempt to keep track of such situations across the country.

It would pay special attention to public universities. With state governments slashing allocations for higher education, public universities have tried to fill the gap through fund-raising campaigns, opening the way for wealthy donors and trustees to gain a greater say in their operations. The most highly publicized case came in 2012 at the University of Virginia, when Teresa Sullivan was suddenly forced out as president. As was widely reported, her ouster was engineered by Helen Dragas, the real estate developer who headed the university’s Board of Visitors and who acted in concert with a small group of board members. They gave only vague explanations for their decision, and as protests by students, faculty, and alumni mounted, the board reversed its decision and Sullivan continues to be president.

Similar but far less publicized clashes have occurred in Texas, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Oregon, and, most recently, North Carolina. There, the Board of Governors of the University of North Carolina, working with Republican legislators, pushed out Tom Ross, the popular president, and in October they announced his replacement: Margaret Spellings, who served as secretary of education under George W. Bush and, more recently, as the president of his library. Many students and faculty protested the decision as reflecting political considerations. A website on money and power would look into such cases and assess the various claims—part of a more general effort to chronicle the activities of the wealthy to reshape higher education in America.

3.

Such a website, in reporting on philanthropists, would pay special attention to the sources of their wealth. Take David Rubenstein, for example. The cofounder and co-CEO of the Carlyle Group, the largest private equity firm in the world, Rubenstein is worth about $2.5 billion. In his giving, he specializes in what he calls “patriotic philanthropy.” He has given $9 million to promote panda procreation at the National Zoo, $7.5 million to help repair the Washington Monument, and $10 million for the restoration of Monticello. After purchasing a copy of the Magna Carta for $21.3 million, he loaned it to the National Archives. These donations have resulted in favorable stories about Rubenstein in both The New York Times and The Washington Post and a glowing segment on 60 Minutes, titled “All-American.”

His generosity is certainly admirable, but from a journalistic standpoint, it has had the effect of deflecting attention from the way he earns his money. The Carlyle Group is known for its secrecy and connections. Nicknamed the Ex-Presidents’ Club, it has had as board members both George Bushes, James Baker, and John Major. From 1992 to 2003, the chairman was Frank Carlucci, the former defense secretary and CIA deputy director, who opened doors for the company in Washington, especially in the defense and intelligence industries, where it acquired many businesses. Carlyle has since branched out into other fields, including telecommunications and media, and in 2014 it hired Julius Genachowski, the former chairman of the FCC, to help spot investment opportunities. In short, Carlyle’s success is to a degree built on its insider connections. So, while Rubenstein’s good works get much attention, the complex workings of the Carlyle Group do not.

The whole subject of private equity has been woefully undercovered. Firms like Carlyle, Blackstone, and KKR have been the main force behind the flood of mergers and acquisitions of recent years. News accounts have focused far more on the market effects of these deals than on their implications for employment, the concentration of wealth, and community welfare. Back in 2012, such factors were closely analyzed in connection with Mitt Romney’s work at the private equity company Bain Capital, but since then interest in private equity has waned even as the field has boomed. Naked Capitalism, an influential financial blog, recently ran a long post about how private equity companies “are far more obviously connected to an undue concentration of wealth at the expense of workers and communities” than are CDOs (collaterized debt obligations) and the other finance instruments that once drew such attention. Though the top one percent of the one percent “consists disproportionately of private equity and hedge fund principals,” the blog ruefully lamented, few of its readers seem interested. The same could be said of the press. A website on the nation’s power elite would pay close attention to the reach and impact of both private equity and hedge funds.

Remarkably, the Wall Street institution that may be the most powerful of them all is also among the least known. BlackRock is the largest money management firm in the world. Its chairman, Laurence Fink, oversees more money (about $4.5 trillion) than Germany has GDP. Fink regularly takes calls from governments and businesses from around the world seeking his advice and, as Susanne Craig reported in the Times in 2012, the company has exerted “enormous influence as a behind-the-scenes adviser to troubled governments” in places like Greece and Ireland. When seeking to analyze the health of a bank, the US Treasury Department often turns to BlackRock, leading a senior bank executive to call it (in an article in Vanity Fair) “the Blackwater of finance, almost a shadow government.” Fink himself is worth more than $300 million and sits on the boards of many institutions, including NYU and the Museum of Modern Art. Nonetheless he and his company have managed to escape serious journalistic scrutiny. A website on money and power could provide it.

Wall Street is hardly the only powerful precinct in need of sharper reporting. Hollywood is another. Coverage of it tends to be thin, with a heavy emphasis on ticket sales, executive rivalries, celebrity interviews, and awards ceremonies. Back in 2005, Bernard Weinraub, in a confessional reflection on the fourteen years he spent covering Hollywood for the Times, described how eagerly journalists sought access to stars and executives and how easily they were “co-opted by the overtures of a Michael Ovitz or the charm of a Joe Roth.”

That’s no less true today. Zenia Mucha, the head of communications for Walt Disney and a top adviser to its chairman, Robert Iger, is known for her skill at cajoling and browbeating reporters. As one journalist who covers the industry told me about Disney, “Almost no one writes a bad word about them so as to have access to top officials.” (He was not, of course, referring to film reviews.) Given the vastness of Disney’s holdings—they include Walt Disney Studios, the Disney Channel, Disney Resorts, Pixar, Lucasfilm, Marvel, ABC TV and News, ESPN, A&E, and Lifetime—assessing Mucha’s alleged success at shaping the news about the company would itself seem a subject worth pursuing.

Silicon Valley is in need of similar probing. Current coverage of the tech world leans heavily toward products, start-ups, and personalities. A website on money and power would instead concentrate on its growing political might. Ten years ago, for example, Google had a one-person lobbying shop in Washington; today, it has more than one hundred lobbyists working out of an office roughly the size of the White House. In addition to such traditional lobbying, Google is financing research at universities and think tanks, investing in advocacy groups, and “funding pro-business coalitions cast as public-interest projects,” as Tom Hamburger and Matea Gold reported in 2014 in The Washington Post.

They described how in the spring of 2012 Google—facing possible legal action by the FTC over the dominance of its search engine—played a behind-the-scenes part in organizing a conference at George Mason University, to which it is a large contributor. It made sure that the program was heavily weighted with speakers sympathetic to Google and, according to the Post, it arranged for many FTC economists and lawyers to hear them. In the end, the commission decided against taking legal action. Just why could be a good subject for inquiry. Today, Google is working hard to protect its right to collect consumer data and to that end has sought the support of conservative groups like the Heritage Foundation. The type of string-pulling described by the Post goes on routinely and deserves more routine coverage.

Finally, there’s corporate America. Once, Fortune 500 companies were the bread and butter of business coverage. Since the 2008 financial collapse, however, the preoccupation with Wall Street has pushed these companies aside. As Jesse Eisinger of ProPublica observed to me in an e-mail, journalists

don’t adequately cover how corporations keep their wages down, treat their employees in general, fight unions, lobby for their corporate needs, arrive at decisions to pay their top executives, or dominate their markets. We don’t hear about the GM or VW scandals until after they break. (Once they do, we get good coverage, but that’s archeology, not detective work.) Where is the coverage of Boeing, 3M, Dupont, FedEx or CVS? Energy? Insurance? Trucking? Construction?

A website on money and power would try to fill this gap. The activities of unions could be examined as well.

The power of the megarich does not stop at America’s borders. As Chrystia Freeland writes in her 2012 book Plutocrats, “the rise of the 1 percent is a global phenomenon,” with the world bifurcating into the rich and the rest. A website on the power elite could offer links to its international members. A page on Mexico’s Carlos Slim, for instance, could point out that his fortune (estimated at more than $70 billion) is equal to about 6 percent of his country’s total annual GDP, helping to make it one of the most unequal societies in the world.

As a 2014 Oxfam briefing paper explained, most of Slim’s wealth derives from his having gained near-monopolistic control of Mexico’s telecommunications sector when it was privatized twenty years ago. Over the seventy years that Oxfam has spent fighting poverty around the world, the report stated, it has seen “first-hand how the wealthiest individuals and groups capture political institutions for their aggrandizement at the expense of the rest of society.” It’s impossible to understand Mexico’s many problems without taking into account Slim’s dominance, yet he rarely appears in reports about that country.

Earlier this year, Slim more than doubled the number of shares he owns in The New York Times Company (to nearly 17 percent), making him its largest individual shareholder (though the Sulzbergers retain control). It’s interesting to note that Slim rarely appears in the paper’s news pages. On the surface, this seems a glaring conflict of interest. Exploring the reality behind it would be an excellent subject for a website on the one percent.

4.

From my research, I’ve come away impressed by the number of informative articles that have appeared on America’s superrich; I’ve cited quite a few of them. I’ve also come to appreciate how hard it can be to ferret out information about this group. I’ve had an especially hard time exploring the influence of big money on the museum and art world. The mega-rich have come to dominate both museum boards and the art market, and through them they have left a deep imprint on American culture, but in my reporting I kept running into roadblocks. Clearly, this is an area ripe for further inquiry.

The same is true of all the other sectors I’ve discussed. For all the good work they’ve done, news organizations have barely begun to penetrate the structure of economic power and influence. That’s why I think a new, independent website on this world is urgently needed. Such an enterprise would cover the super-elite with unflagging single-mindedness. It would dig deep into the worlds of hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, and mergers and acquisitions, treating them not as arenas of Wall Street wheeling and dealing but as avenues of financial maneuvering that have significantly fed the economic imbalances in this country. It would devote sections to philanthropy, think tanks, lobbyists, advocacy groups, education, cultural institutions, Hollywood, Silicon Valley, corporations, and foreign tycoons and show the cross-cutting ties among them. The information gathered would be fed into a constantly updated database, allowing users to learn with a few keystrokes about hedge fund managers’ backing of charter schools, influence-seeking donations to Brookings and AEI, Google’s latest lobbying venture, and the promotion of Ayn Rand on campus.

The website could also feature bloggers able to expose the internal workings of Wall Street. It could dispatch video crews to exclusive enclaves like Greenwich, Connecticut, and Palm Beach, Florida, to show the opulent mansions and cloistered lifestyles of the super-haves. It could post analytical dispatches from such elite gatherings as the Boao Forum (Asia’s Davos), the Zeitgeist conference (a Google version of TED), Sun Valley (where media barons meet annually to make deals), and Bilderberg (the most secretive executive conclave in the world). It could hire a press critic to document cases of the media accommodating the rich and show what’s not being reported. It could even produce John Oliver–like send-ups of the many ways in which corporations use front men, researchers-for-hire, and fake grassroots groups to try to influence and mislead the public.

There remains the question of how to pay for all this. Given the sizable staff that such an enterprise would require and the limited potential for advertising, it’s doubtful it could ever turn a profit. That means relying on philanthropy. Is there perhaps a consortium of donors out there willing to fund an operation that would part the curtains on its own world?

—This is the second of two articles.

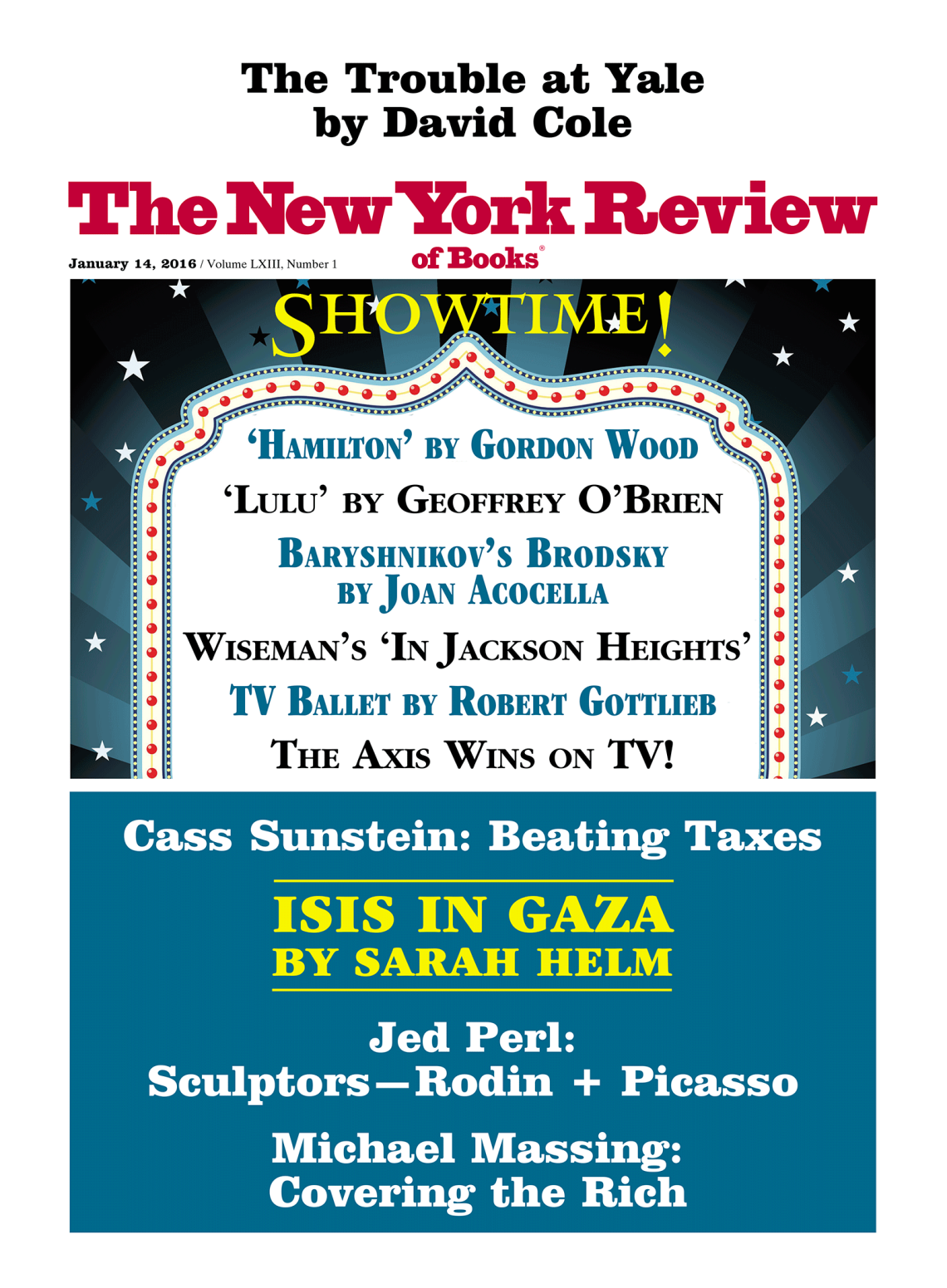

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

A Ghost Story

-

1

“Reimagining Journalism: The Story of the One Percent,” The New York Review, December 17, 2015. ↩

-

2

For an example of the type of analysis such a website could offer, see Alessandra Stanley, “The Tech Gods Giveth,” The New York Times, November 1, 2015, which raises questions about how much radical change Silicon Valley philanthropists truly support. ↩