For Joshua Levin, the hero of Aleksandar Hemon’s marvelous comic novel The Making of Zombie Wars, daily life is a source of inspiration, a succession of bruising encounters and near-continuous mortifications that can be mined for the premises of awful films that will never be produced. Scattered throughout the book are Joshua’s plans for screenplays, each numbered and with a title and plot that are, even by Hollywood standards, at once preposterous and banal, yet the mind that conceived them has clearly absorbed many movies. Stoned on pot, Joshua goes on a wild, nauseating car ride through Chicago with his landlord, named Stagger, a veteran of Desert Storm who suffers from PTSD, and is more or less handy with a samurai sword. Joshua translates this nightmarish experience into an idea for yet more bad art:

Script Idea #196: A rock star high out of his mind freaks out during his show, runs off the stage, and finds himself lost in a city whose name he can’t recall, but whose streets are crowded with his hallucinations. A teenage fan discovers him trembling behind a garbage container, begging the Lord to get him out of his trip. The teen decides to keep the rock star for himself for the night. Mishaps and adventures follow. This one could be a musical: Singin’ in the Brain.

While trying to write at a coffee shop, Joshua watches a group of ROTC cadets and imagines them “in the desert, thickly coated in dust, tongue-hanging thirsty on their way to a battle where they would mature and/or heroically die, the nefarious natives offering them contaminated piss-warm water in beaten tin cups.” Thus the idea for his magnum opus, Zombie Wars, is born:

Out of the sad ROTC mindlessness the scene from Dawn of the Dead was recollected in which zombies tottered in circles around a depopulated shopping mall unable to forget their life before their undeath, their infected brains still retaining the remnants of their happy Christmas memories…. In a blissful blink, Joshua saw the narrative landscape neatly laid down before him: all the endless possibilities, all the overhead and wide shots, all the graceful character trajectories blazing across the spectacular firmament, all the expanse conducive to a love interest—all Joshua had to do was stroll through that Edenic symmetry and write it down.

Acutely self-aware, and painfully self-conscious, Joshua is not getting a great deal of satisfaction from his career as a pretend screenwriter. He supports himself by teaching “English as a Second Language” in a school founded primarily as a “noble scam” to divert funds earmarked for providing educational visas to Soviet Jews into “a resettlement program, a leftover from the heroic, Operation Exodus times.” Among his students are a cranky former KGB agent and his wife, neither of whom bothers to hide their contempt for “Teacher Josh”; a Dostoevsky-quoting ex–rocket scientist who insists that Joshua help him translate an antiquated VHS-player manual; two Russian matrons uninterested in “English grammar or anything at all save for the intimidating presence of black people in their new country.” “The only bright light in all that post–Cold War darkness” is Ana, a Bosnian woman whose mournful beauty tests Joshua’s fidelity to his girlfriend, Kimiko, a child psychologist so sexy, loving, and smart that Joshua cannot resist the impulse to prove his unworthiness by plunging her orderly existence into chaos and horror.

Hoping to advance his career, Joshua himself is attending a workshop, Screenwriting II, taught by a windbag named Graham whose pedagogy combines useless advice, obscenity, bullying, and bombast:

“‘Blessed be the amateurs!’” Graham spoke in the bloated voice of one of his cardboard characters. “‘The triers, the failers, the shit-swimmers! Let us praise those who dream big and achieve nothing, those undaunted by impossibilities, entrapped by possibilities! They are the dung beetles of the American Dream, the unsung little fertilizers of American soil.’”

One of Joshua’s classmates, Bega, has been working, or claiming to work, on a script built around the outline of his life in Bosnia, which he presents to the class:

Man is from Sarajevo. He was happy there. He was young, he had rock group, had women. War came. He is refugee now. He goes to Germany. They are Nazis there. He works like security in disco, plays his guitar only for his soul. He drinks, remembers Sarajevo, writes blues songs. Comes 1997, Nazis throw him out. He goes back to Sarajevo, but nothing is same. Heartbreak…. Man has no more friends in Sarajevo. Half of his group is dead, other half everywhere. Women have husbands. Everybody talks about the war all the time. He says, Fuck it! and goes to America—country of Dylan and Nirvana and best basketball. But he lost his soul. And American women are all feminists.

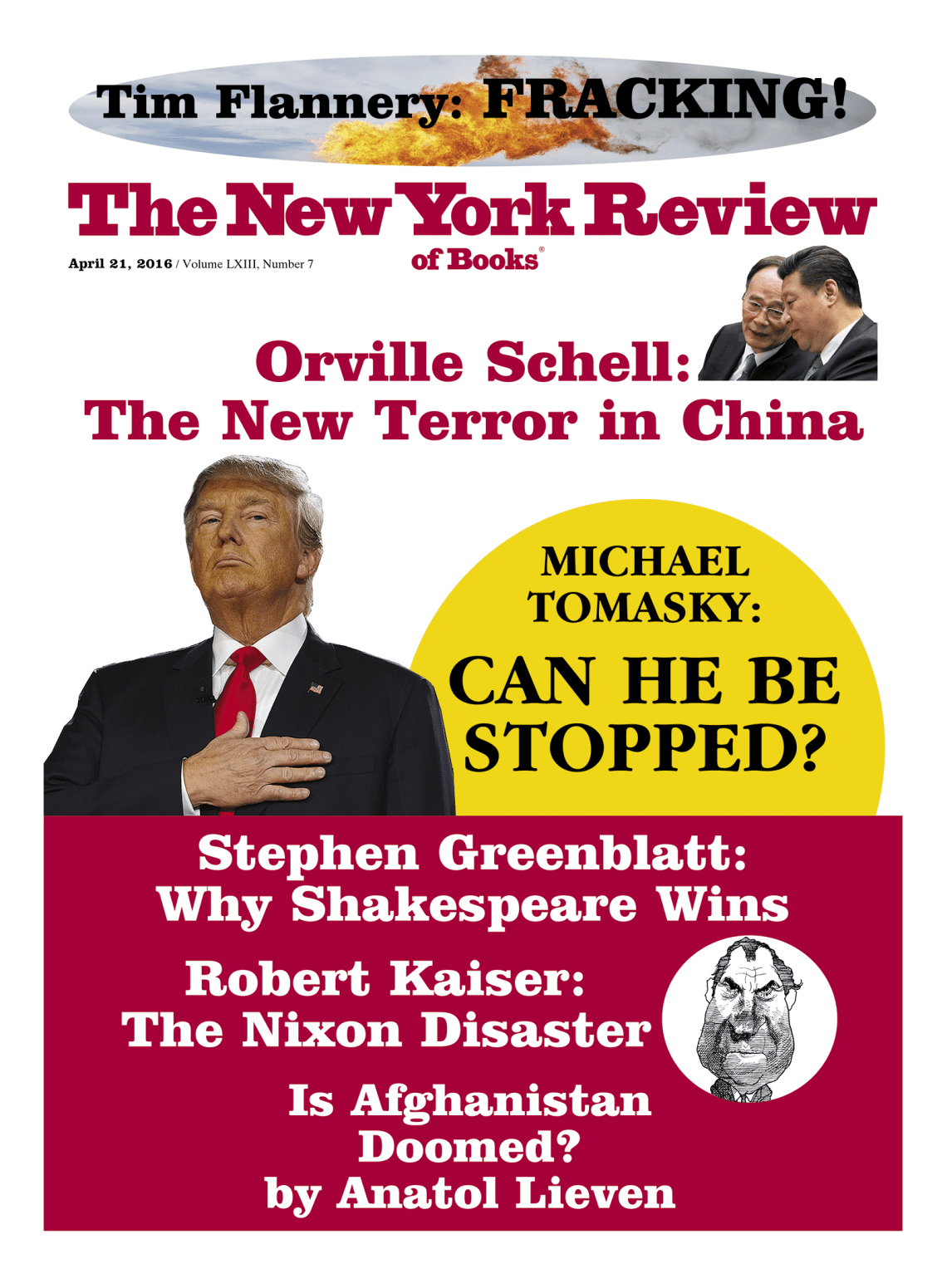

Under Graham’s tutelage, which mostly consists of taking up his students’ ideas and running with them in the wrong direction, Joshua’s vague plans for a “zombie film” are modified to reflect the mood of the year—2003—during which The Making of Zombie Wars is set. With typical incoherence, Graham proposes that

Advertisement

“Maybe the army can also fight some, like, terrorist zombies, blowing themselves up like crazy. It’s a good time to be thinking about all that, given that we’re just about to tear a new hole in the ass of Iraq.”

“I didn’t actually think of that,” Joshua said.

“It could be fun, believe me. We unleash the zombie army at the camelfuckers and then it all flies off the handle and our undead boys come back to feed on our flesh…. Hey, they took our towers down. Revenge is a dish best served with carpet bombing.”

When Joshua protests that Graham’s suggestions are too political, Bega insists that “everything is political. Everybody is political.” This will turn out to be one of the many things that Bega knows more about than Joshua, and that Joshua will learn at great cost. In fact everything in the novel is political, cloaked but never fully concealed by humor and high spirits. Within just a few pages, the ingeniousness of Hemon’s method has become apparent: he uses the ludicrous workshop to evoke the specter of two of recent history’s most brutal wars.

The damage that those conflicts have inflicted on several major and minor characters will produce enough havoc to loosen Joshua’s tenuous grip on himself. And even during the more placid scenes, history and politics are ominously present in the background. In restaurants and hospital rooms, television screens monitor the progress of US troops marching toward Baghdad. When Joshua and Bega go out for a drink, George W. Bush appears on the TV in the bar, “his face so decisively earnest that it was clear he was lying, his button eyes lit up with amateurish subterfuge. Only truly great men can be adept at shameless lying, Joshua thought. This dude was straining to the point of snapping.”

On his way to lunch with his father, Joshua sees a man who looks exactly like Dick Cheney—“pale and bald, egg-shaped head, rimless glasses, the detached gaze of a sociopath”—sitting alone in a car parked on a block where gay men cruise for casual sex. The sighting of the Cheney lookalike is merely a detail of the scenery. In the foreground is Joshua’s fraught relationship with his father, Bernie, a retired dentist who has left his family for a woman named Constance:

Bernie honked from his ferry-sized white Cadillac. In addition to the glaring absence of sun, Bernie’s shades were not age-appropriate at all: the frames were too narrow for his sagging face; there was fake-diamond glitter on the sides; and the lenses were far too dark even for a bright summer day, suggesting glaucoma rather than senior coolness. The shades were most likely Constance’s present, just like the flannel shirt he was wearing with his sleeves rolled up, like a campaigning congressman feigning to be the American people. Constance bought things for Bernie Levin that made him appear younger (a razor-looking cell phone, many-geared bicycle, surfboard) thereby constantly setting up Bern (as she called him) for some kind of age-based failure.

Part of what makes Joshua sympathetic and interesting is the deftness with which Hemon portrays his shifting consciousness, constructed from, and perpetually modified by, fragments of daily experience. We become privy to a private vocabulary composed of phrases that Joshua has heard, of images we’ve watched him see, of fantasies that have crossed his mind—and have gotten stuck there. Dillon, the dimmest participant in Screenwriting II, describes his script-in-progress:

They’re like in the desert…and there are like all these things. He like stops by the fear booth and these like guys ask him what his fears are and he says, it’s like sharks and waves, and these like guys come out dressed as his worst fears and like follow him around.

The image of “the fear booth” recurs much later as Joshua discovers how much there is to be afraid of. “A centrifuge of terror spun in his stomach. He couldn’t have imagined that the fear booth could offer services like this.”

When Ana, Joshua’s lovely Bosnian student, asks him how old he thinks she is, and he replies “thirty” though he guesses she might be closer to forty, her spontaneous response—“I can kiss you for that”—becomes an obsession: “Whenever Ana’s husband reappeared, Joshua tried for eye contact with him, so as to exhibit his honesty and innocence, thereby covering up his humming desire. I can kiss you for that, she said.” After Bernie is diagnosed with prostate cancer, Joshua’s fixation on the “evil cell” menacing his father ruins his pleasure in a glass of wine:

Advertisement

Joshua swallowed half of his glass. Interesting: a touch of Chapstick, ginger-ale nose, cat-hair finish. He couldn’t remember the last time he actually enjoyed wine. Perhaps his nose was changing; perhaps his body was changing; perhaps an evil cell had already hatched in his groin.

And Kimiko’s habit of referring to the children she sees in her psychology practice as “little patients” colors Joshua’s view of Ana’s adolescent daughter:

What’s wrong with teenagers? Joshua wondered. Indestructible, they come into and out of hell as they see fit. The little patients have so much of themselves and they know more is always coming, so they can afford to keep wasting it. One day, sooner or later, they run out of themselves and enter punitive adulthood. Once you mature, you start spending your limited life, every day one fewer to live.

Among Joshua’s qualities is his passion for Spinoza, and his tendency to use daily events and ordinary objects as opportunities to refer to the work of the Dutch philosopher, or to the Bible. A heap of shoes left on the floor outside a party sparks a chain of associations that includes thoughts of his grandparents, and ends with a line from Spinoza’s Ethics:

There were women’s high heels too, and flat ballet shoes and even flower-patterned rain boots. Visions of the Holocaust shoe heaps came to Joshua and in their wake a memory of Nana Elsa’s Florida plastic flip-flops, conforming to her bunions perfectly. She’d had them for at least fifteen years and wouldn’t hear of getting rid of them. In fact, she never got rid of any of her shoes; Papa Elie disposed of them behind her back, so she never let her precious flip-flops out of sight. She wanted to be buried with those flip-flops. Nothing exists from whose nature some effect does not follow.

In the midst of sex with Ana, he recalls a quote from the Psalms: “Too distraught to look her in the eye, he put his hand on her knee, then pushed her skirt up. It turned out she wore no underwear. He who provides food to all flesh, everlasting is His loving kindness.”

Not only is Joshua fascinated by the great thinkers of the past but he is given to metaphysical, philosophical, and political speculation of his own. Just after he begins his affair with Ana, he thinks:

Feeling no remorse was a new and powerful sensation: the frigid snap in his lungs, the tingling fingertips on the duffel bag handle, the vapor of his own breath washing over his face. This was real, this Joshua in this aftermath, for whose actualization sex was just a prompt. It was like finding a new, big room in the overfurnished house of his self…. This was, he understood, why men cheat, why all mankind are liars—the power of acting without regret, the destruction of remorse. It wasn’t the sex: it was the freedom to take or do what you want. The presence of death, the gaping void, afforded entitlement. This was what wars were for.

The Making of Zombie Wars deals with a remarkable range of serious, and some less serious, topics—sex, death, family, war, the Bush-Cheney years, immigration, morality, America, zombies, and the meaning of life—without ever being didactic or sententious. Frequently, Hemon puts penetrating remarks into the mouths of lunatics and idiots, as when the workshop discusses how zombies and America are portrayed in Joshua’s screenplay:

“It’s not about the zombies, it’s about the living,” Joshua said.

“But living don’t do nothing in your story,” Bega said. “They just kill lot of zombies. Good thing about zombies is you can kill million and nobody cares. You just shoot, they explode, nobody cares. It is for Americans to feel better about killing to make it easy.”

When Joshua and Bega suggest that the hero of Joshua’s script might be sad, Graham seizes control of his class:

Fuck sadness, movies are not about being sad…. Look anywhere around you, no sadness. Americans are proud people but we’re not sad people. We’re either deeply depressed or insanely happy. Either way, we don’t care to see other people’s misery. What we want to see is how to overcome the shit. We shall overcome! Overcome the shit! That kind of thing.

Along with observations about writing and film Hemon succeeds in suggesting some of the ways in which the workings of the economy and meretricious argument have warped American culture. One day, Joshua has lunch at a sushi restaurant with a producer who, according to Graham, could help him sell his script to Hollywood.

“Let’s pretend we don’t know each other at all,” Billy said. “Let’s pretend we’re at a party. Everybody’s drunk out of their minds. There’s an orgy with a rotating cast in the spare bedroom. You have exactly five seconds for your pitch. Sell me Zombie Wars.”

His mouth loaded with unagi, Joshua slowed down his chewing to think of the way either to avoid this test or, if that proved difficult, to get up and walk away….

“Zombie Wars is a story of an ordinary man trying to survive in difficult circumstances,” he ventured.

“Not bad. Not bad at all. But let me give you some advice. Never, ever use the word ordinary when you pitch. Ever. Another thing: trying. Heroes don’t try. They either do it or they don’t. Mainly they do it. Survive: verboten! Unless it’s a Holocaust story. And circumstances has too many syllables, easy to fumble.”

What soon becomes clear is that the jokes in Hemon’s novel are not just jokes, but about something larger, whether political, philosophical, or moral. Like all the best comedy, the novel makes it impossible not to sense the melancholy beneath the sullenness and absurdity. Hemon’s wit prevents the novel’s often emotional passages from seeming sensational or sentimental, while an intensity of feeling keeps the funny bits from appearing easy or shallow.

One can watch this at work as Joshua and Bernie have lunch at Charlie’s Ale House. Joshua’s description of his Zombie Wars screenplay, which prominently features a zombie virus, prompts Bernie to tell a story about a Jew who was informed by a rabbi that he couldn’t die until he regained his faith—and who survived the Holocaust by remaining an unbeliever.

“Nice story,” Joshua said. “What’s your point?”

“Maybe it’s not the virus. Maybe it’s that zombies lost faith.”

“You are something, Bernie!” Joshua said. “Zombies are self-hating Jews? If you don’t stand by Israel, you are one of the living dead? Is that what you’re saying?”

Bernie shrugged in the manner that was part of his annoying repertoire: slanting his head to the side, scrunching his shoulders, his face signaling, Maybe I know nothing, but I’m just saying—the shtetl shrug.

“It’s just a virus, all right?” Joshua said. “It’s a convention. Suspension of disbelief. Those who care about the story accept that it’s a virus, they don’t question the goddamn virus. It’s like these weapons of mass destruction—Saddam has them because he’s Saddam. If there are zombies there is a virus. The zombie virus. That’s it. Can we drop the fucking virus?”

Bernie read the menu, squinting—another annoying thing—and moving his glasses up and down his curled-up nose to zoom in and out. Joshua knew that what he hated about the moments like this would end up being precisely what he missed about his father when he was gone—his irritating tics would be converted into heart-wrenching recollections.

Joshua’s sympathies are broad and capacious enough to inspire him with pity for the senior George Bush. Joshua recalls his surge of compassion for the former president immediately after Bernie first remarks that he hasn’t been feeling well:

Joshua had once watched Bush the Elder address the nation from the Oval Office. He was about to send our troops to some godforsaken place and highfalutin drivel was required to placate further the already indifferent American people. He was front-lit, the better to deliver the platuitudes, so the Oval Office window behind him looked unreal, like a painted set. But then, in the middle of presidential bullshit, Joshua sensed a slight motion behind Bush and spotted a tree leaf falling, twirling through the frame of the backdrop window, which hence became real. The deciduous leaf suddenly made Bush look terribly old, and getting older by the instant. Mr. President was going to die and no troop deployment could ever stop that.

Near the book’s conclusion, a scene of mayhem and carnage involves Joshua, Stagger, the samurai sword, Ana, and her husband Esko. Joshua is inspired to come up with a different kind of screenplay:

Stagger grunted and sat up. He grabbed a filthy napkin from the floor and pressed it against his nose. Ana kept repeating some Bosnian word, something, Joshua knew, she would never say to him. He wanted her to reconcile with Esko, thereby restoring some semblance of order, thereby allowing him to return from this exile to the land of the before, where there was no humiliation, no blood, no frogs, no lice, no locusts, no clotted darkness or pain, no chaos, let alone the possibility of urine-soaked underwear. Script Idea #1: Two or more people. Love, life, betrayal, hurt. Title: God Help Us All.

After this violent—and cathartic—episode, we may begin to fear that there’s no way to end Hemon’s story, no resolution that won’t betray the honesty and undermine the moments of plausibility with which Hemon has infused his antic narrative. Yet he finds a way by setting his penultimate scene at Joshua’s family Passover seder, to which the Levins have invited Stagger. There’s tenderness, sorrow—and humor—in the counterpoint between the domestic drama (consoling, irritating) and the story of Moses liberating the Jews from Egypt.

The fact that the scene is written in the form of a screenplay might lead us to assume that Joshua has outgrown his fixation on the zombie wars. But we would be wrong. Once more The Making of Zombie Wars surprises us, in this case with what is surely the most evocative and moving scene in the history of zombie literature. Hemon succeeds in doing several things at once: he writes the sort of conclusion that likely would have been mandatory had Joshua’s screenplay ever been made into a film, and at the same time he creates a troubling, mysterious, lyrical elegy to the world in which the living struggle to maintain their fragile truce with the undead.