In the opening paragraph of The Lady with the Borzoi, Laura Claridge provides a highly compressed and useful explanation of why one might want to read a biography of Blanche Knopf, who profoundly and permanently influenced the American public’s ideas about, and taste in, literature. In the early years of the twentieth century, Blanche

began scouting for her fledgling publishing house quality French novels she’d get translated, such as Flaubert’s Madame Bovary and Prévost’s Manon Lescaut. Soon she would help Carl Van Vechten launch the literary side of the Harlem Renaissance, publishing works by Langston Hughes and Nella Larsen, while she also nurtured and often edited such significant authors as Willa Cather, Muriel Spark, and Elizabeth Bowen. Through Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, and Ross Macdonald, she legitimized the genre of hard-boiled detective fiction…. She introduced to American readers international writers whom she met and had translated into English, among them Thomas Mann, Sigmund Freud, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir.

Born in 1894 and raised on the Upper East Side, Blanche Wolf came from a wealthy family with limited expectations for their daughter: they hoped only that she would find a husband who could accelerate their ascent (her father had been a farmworker in Germany; her maternal grandfather owned a slaughterhouse) into Jewish high society. The Wolfs saw no reason to send Blanche to college. But the Gardner School, an institution “aimed primarily at well-off Jewish girls,” introduced her to “an enchanted universe” where she developed a lifelong passion for nineteenth-century novels and French literature, language, and culture.

Increasingly bookish, contemptuous of the friends she had begun to view as frivolous and shallow, Blanche often read while walking her Boston terrier. She showed little interest in boys until, at seventeen, she met Alfred Knopf at a party on Long Island. Knopf, whose father, Sam, had emigrated from Poland and become the director of a small mercantile bank, was impressed by the fact that Blanche “read books constantly and he had never met a girl who did.” Blanche’s family had many reasons for opposing the marriage, among them the apparently well-grounded suspicion that Sam’s father had driven Sam’s mother to suicide. But the lure of a life in literature was too heady for Blanche to resist. “We decided we would get married and make books and publish them.”

By the afternoon of their wedding at New York’s St. Regis Hotel, in April 1916, Blanche and Alfred Knopf had been in business together for a year. The previous spring, the idealistic young couple had founded the company that, a century later, still bears Alfred’s name. Among the offerings on their initial list were books on Russian history and politics, a story collection by Guy de Maupassant, and Gogol’s Taras Bulba. Clearly, the Knopfs were not planning a wildly lucrative venture, but rather a serious enterprise that would bring out handsomely designed editions of foreign classics and worthy new works by American authors.

A few early commercial successes—Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, which “proved a major moneymaker for Knopf throughout the company’s history,” and a reissue of W.H. Hudson’s Green Mansions—helped ensure the firm’s stability. Willa Cather’s One of Ours (1923) was the first Knopf book to win a Pulitzer Prize, and the vigorous sales of Cather’s novels, as well as the popularity of H.L. Mencken’s The American Language—a study of the differences between the British and the American use of English—proved that literary books could be profitable. Alfred’s father provided the couple with office space and volunteered to serve as their business manager, though after his death, it would turn out that the poor judgment of Blanche’s “overbearing” father-in-law had precipitated a fiscal crisis that nearly derailed the company.

Decades later, Blanche would claim that, before the wedding, she had extracted a verbal promise from Alfred: they would be equal partners in the business. “But once they married,” writes Claridge,

the ‘mutual understanding’ was disregarded. Eventually Alfred would explain unconvincingly that because his father planned to join them at the firm, her name could not be accommodated: three names on the door would be excessive. Moreover, she would own just 25 percent of the company while Alfred owned the rest.

Blanche’s name was omitted from the elaborate testimonial book that Alfred had printed in honor of the firm’s fifth anniversary.

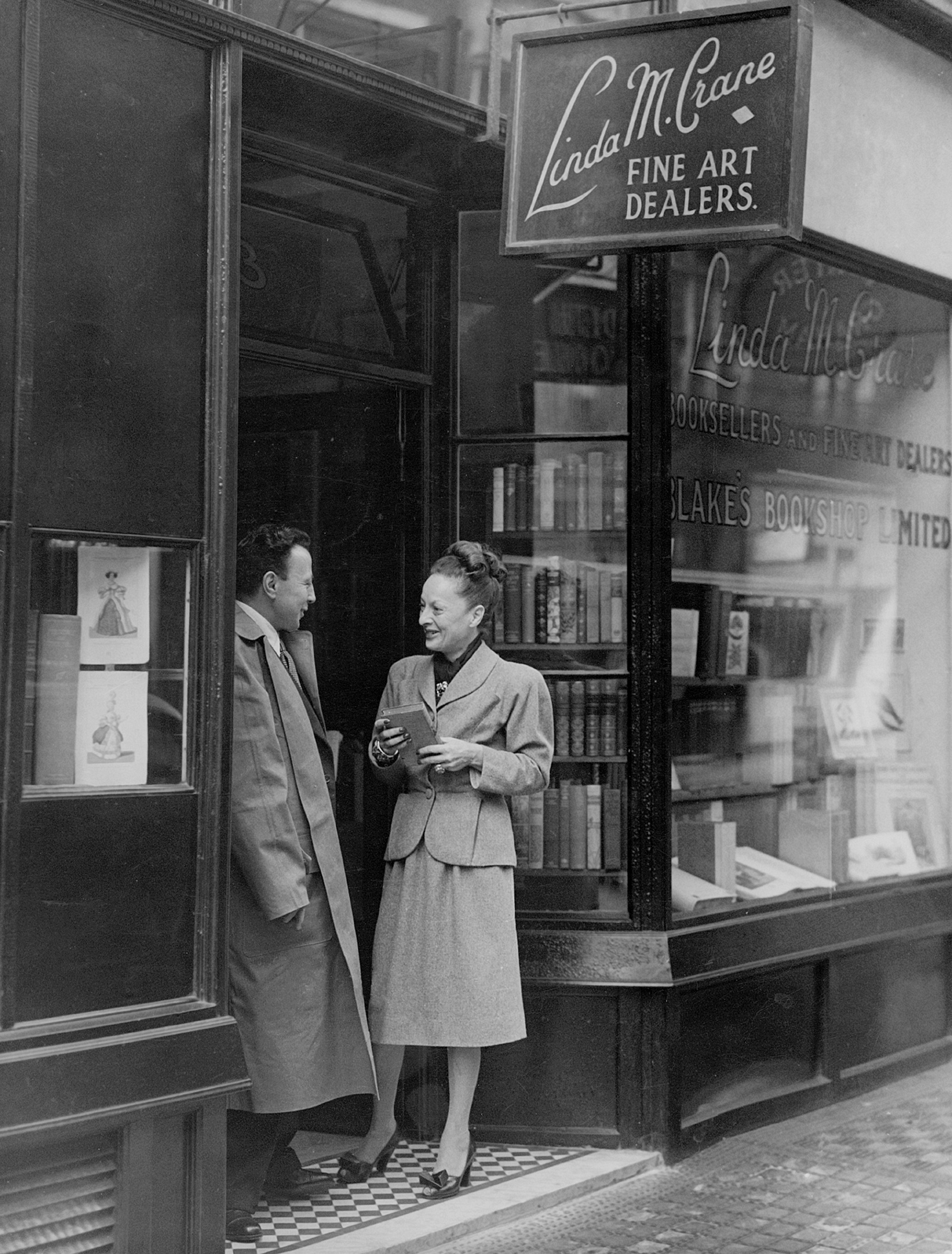

By the tenth anniversary, matters had only marginally improved. In an interview with Blanche, a female reporter from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle kept changing the subject from Blanche’s work to that of marriage and motherhood, even though Blanche insisted, “I didn’t marry the business, I helped start it.” Three years after Blanche’s death in 1966, Alfred said, “Looking back to the days when I was on the board, the idea of a woman being part of it is something that I simply cannot become reconciled to.” Much of Claridge’s biography is framed as an attempt to redress an injustice and to answer certain questions raised by Blanche’s life and legacy. How could a woman who achieved so much have been so undervalued, and how could she have become, over time, less visible than her dog, the elegant borzoi whose image, “perpetually on the move,” still serves as the logo of the publishing company that she cofounded, codirected, and to which she was wholly devoted?

Advertisement

Happily for Blanche, Alfred soon “discovered that he enjoyed selling books more than actually working on them—or even reading them,” and he began spending much of his time on business trips away from the Knopf headquarters on West 42nd Street. Despite the bad behavior of her father-in-law, whose bullying drove Blanche to flee the office and hide, weeping, in the lobby phone booth, she reveled in every aspect of her new profession:

Organized by nature, she managed the fledgling business, signing contracts with writers she’d found or approved, checking out translators, deciding upon bindings…as well as choosing the printing company best suited to the book at hand…. Studying typography, paper, ink, and the mechanics of printing presses, she found every facet of publishing fascinating. Above all, her love of reading was gratified by the hours she spent devouring manuscripts delivered by her growing network of writers.

Blanche proved a superb editor of fiction and poetry: she listened to the rhythm of the language on the page and reacted to phrases, vocabulary, even punctuation, as she considered who might be right for Knopf.

Blanche’s talent for discovering some of the best books being written was abetted by her gift for friendship. Throughout her career, she was greatly helped by sympathetic agents familiar with the international scene, and by writers who introduced her to other authors, and who helped broaden and refine her literary sensibility. It was through H.L. Mencken that Blanche met Thomas Mann, whose novels, beginning with Buddenbrooks, she would publish in scrupulously vetted translations. Carl Van Vechten was her “personal guide” to the jazz and literary scene in Harlem, where Blanche became acquainted with Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, and Nella Larsen. Willa Cather chose to publish at Knopf “in large part because she bonded with Blanche, who knew enough to tone down her appearance when the stolid writer came to visit and to let Cather take the lead as they talked.”

Blanche counted Fannie Hurst, Elizabeth Bowen, Muriel Spark, and Rebecca West among her close friends. The Paris literary agent Jenny Bradley directed her attention to the work of Albert Camus, with whom Blanche had a highly charged but apparently platonic relationship. (“Who would have guessed you would be the one I’ve been seeking all my life?” Blanche wrote him.) Blanche lobbied hard for Camus to win the Nobel Prize and, outfitted in Dior and Balenciaga, she accompanied him to the 1957 award ceremony in Stockholm.

Blanche’s rapport with her authors had much to do with the lengths to which she was willing to go in order to make them feel valued. She arranged for Thomas Mann’s New York hotel room to be “festooned with flowers” and bought shoes at Saks for Elizabeth Bowen, who

thanked Blanche by joking that ‘Alan [her spouse] loved the shoes too; he [is] just short of being a fetishist.’ Blanche had no difficulty incorporating the purchase of footwear into her routine, if it meant making a writer…happy.

Ambitious, competitive, prodigiously energetic, she was tireless—and fearless—in her efforts to find new authors for Knopf. In 1943, during World War II, she flew to London and, during the nightly bombings, stayed at the Ritz to meet with Edward R. Murrow and James “Scotty” Reston. Nervy and frequently confrontational, she took on the “notoriously irascible” Lillian Hellman when Hellman accompanied Dashiell Hammett, one of Blanche’s writers, to the Knopf office. Congratulating Hellman on the success of her play The Children’s Hour, Blanche

offered to publish it with an advance of “$150.00.” Hellman responded, “$500.00.” Blanche looked her squarely in the eye and said, “Why does a girl who’s sitting over there wearing a brand new mink coat need $500?” But she paid it because she wanted the play—and to ensure, as long as she could manage him, that Hammett would stay with Knopf.

Only rarely did Blanche’s bravery desert her—for example, when she decided against publishing books that seemed likely to involve potentially costly censorship cases: D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness.

Advertisement

Blanche Knopf’s accomplishments and the intensity of her focus seem all the more remarkable when one considers the distractions of her tumultuous personal life, and the periods of instability brought on largely (as Claridge views it) by her troubled relationships with her husband, her son, and at least one of her lovers. The Knopfs’ marriage appears to have been unhappy from the start. When they wed, both husband and wife were virgins who soon discovered that their passion for literature was the most—and quite possibly the only—erotic aspect of their connection. When Alfred flirted with a childhood friend, “the recent bride was confused that her husband already seemed interested in other women, though he seemed uninterested in making love to her.” Claridge speculates, somewhat confusingly, about the nature of Alfred’s sexuality:

Given the times, when “aberrant” behaviors weren’t seemly to advertise, his chilly reserve toward Blanche might make more sense if he’d been homosexual. Instead, it seems that Alfred simply lacked a physical need to connect emotionally with anyone, so he procured prostitutes instead.

Numerous anecdotes illustrate the vehemence of the couple’s mutual antipathy and the damage inflicted by Alfred’s coldness and insensitivity, yet it is also clear that they were, in their way, very close. “For all her marital disappointments, Blanche still wanted Alfred’s heart,” Claridge writes. She includes excerpts from letters filled with expressions of affection. “Darling: I miss you much more than ever before…. It is better with you than without you anywhere!” Blanche wrote Alfred in 1953. That same year, when Alfred’s sister-in-law Mildred asked him whom he wanted to sit beside at a dinner, he replied, “‘You know there is only one woman in the world for me.’ As Mildred had surmised years before, ‘It’s the old story: he couldn’t live with her, he couldn’t live without her.’” A Knopf employee opened Alfred’s private diary to read, “Blanche says I don’t love her but I do.”

Claridge describes the marital confrontations that disrupted Knopf editorial meetings. (“The volatile Alfred antagonized Blanche…swooping down on her just as she thought there was an all-clear.”) But a board member who recalls them “lying in wait for the other to make a misstatement” also adds, “we were always sure Alfred was absolutely crazy about Blanche.”

The most damning reports on the Knopf marriage come from their only son, Alfred “Pat” Knopf Jr., with whom Blanche had a turbulent relationship, and who recalls “his mother yelling because his father was beating her up.” But Claridge expresses some doubt about the younger Knopf’s reliability. “Given Pat’s complicated personality, it is hard to know what to trust.” According to Frances Lindley, a Knopf editor and one of Blanche’s friends, “Pat’s capacity for self-awareness is as limited as his father’s. He always overacted antagonism to his mother.”

In 1921, while staying at the country house of the British publisher Sir Newman Flowers, Blanche attempted to kill herself by taking an overdose of pills—an act that Claridge conjectures, not entirely convincingly but in keeping with the themes of her biography, to have been the consequence of professional disappointment:

It seems possible, at least, that the episode expressed Blanche’s despair at having been omitted from the Knopf five-year celebration, an omission that reverberated with industry people she met on this trip…. She had trusted Alfred to ensure that she played an equal part in building and running Knopf, and she had believed he would add “Blanche Knopf” to the firm’s name eventually. Instead, he had betrayed her, and, now suspecting he didn’t plan to ever include her name, she became despondent.

Claridge is more persuasive when she attributes some of Blanche’s problems to her obsession with being thin. At times she survived on lettuce, celery, and olives, and she asked a doctor to help her reduce her weight to seventy-five pounds. She also experimented with harmful diet drugs (amphetamines, Mencken believed) and a chemical, DNP, “used during World War I by the French to manufacture dynamite…effective for calorie loss but capable of literally cooking people to death internally if they took too large a dose.”

Neglected by her husband, “Blanche came up with ever-shrewder ways to have a real sex life.” She sought solace with a succession of lovers, including several brilliant musicians, among them Leopold Stokowski, Jascha Heifetz, and Serge Koussevitsky. “Without fail, as if marking them, she gave each of her lovers a solid-gold Dunhill cigarette lighter and case, monogrammed, though there is no record of Blanche having received such gifts from the men.” She was even more generous with the considerably less talented, German-born Hubert Hohe, described here as “one of those foreign charmers,” “a supposedly successful Manhattan stockbroker,” and “a gigolo.”

Forty-five when she met Hohe, Blanche considered him to be her great love and set him up in an apartment next door to her own, a kindness he repaid by stealing her gold flatware and leaving her for other women with whom he had noisy, “violent” sex against the thin wall that separated his triplex from Blanche’s. Yet despite Blanche’s romantic disappointments and professional setbacks, she seems to have been capable of having an extremely good time. After mastering the dances popular in the 1920s—the Charleston, the Lindy Hop, and the Black Bottom—she gave a dinner party during which she

mysteriously disappeared, to return in top hat and cane, play a 78 on the Victrola, and perform a medley of all three dances with heady confidence. Alfred applauded vigorously, even as the guests seemed unsure what to think.

On some days she awoke at dawn to go fox-hunting in Westchester or Connecticut, “returning to the office in time for meetings and to work.” She was unfailingly stylish, dressed in couture, and loved giving—and attending—lavish parties that allowed her to combine business with pleasure:

Often Blanche went to Elizabeth Arden…to get her hair and nails done, preparing for her evening work: acting the socialite, attending endless parties and musical events on the arms of friends, making sure she was seen while she herself was always on the lookout for a book idea that could come from anywhere or anyone.

One can imagine that The Lady with the Borzoi must have been a challenge to research and write, in part because, according to Claridge, Blanche had a penchant for fabricating and mythologizing her personal history. Though her father, Julius Wolf, is listed on his immigration documents as having been “a farmer or day laborer (‘Landmann’) in Bavaria,” Blanche referred to him as a “gold jeweler from Vienna.”

There are many passages in which the biographer speculates about what Blanche must have felt or thought. (“Blanche surely felt the shame of the battered wife, the sense that she had done something wrong, along with a growing rage she worked hard to suppress.”) Meanwhile one longs to hear more about what Blanche actually did think about the books she published—about the ways in which her taste was formed, about precisely what she looked for and admired about the writers she pursued and courted. Given that she lived in an era when people communicated by letter, when editors and publishers wrote reports on the books they championed, and when galleys were corrected by handwriting, it seems strange that we read so little about her literary criteria, about the editing process at which she apparently excelled, about the cuts and changes she persuaded her writers to make. Doesn’t such documentary evidence exist—if not in the Knopf collection at the Ransom Center in Austin then in the archives of the writers with whom Blanche worked?

On occasion, we are given general remarks that Blanche made in letters to Alfred, among them her assessment of Richard Hughes’s novel The Fox in the Attic: “There is not a word wasted so that it is slow-going and brilliant and probably the best picture of post-first war Germany that has been written.” The closest we come to hearing about specific changes that Blanche requested occurs in a section about the editing of James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain. Blanche deputized her editor, Philip Vaudrin, to persuade Baldwin to tone down the book’s “rough language,” but it seems that these proposed changes were motivated by anxiety about the censors rather than by purely literary concerns. Vaudrin wrote Baldwin:

Nothing serious, as you will see, but all advisable from the point of view of censorship…. The phrase “and rubbing his hand, before the eyes of Jesus, over his cock” now reads “and making obscene gestures before the eyes of Jesus.”

Baldwin rejected changes to his next novel, Giovanni’s Room, and Knopf passed on it.

There’s a tantalizing excerpt from Blanche’s letter to Sigmund Freud, who, believing that he’d omitted essential material from the German text of Moses and Monotheism, decided to make extensive alterations in Knopf’s English-language translation. “Since all details of the translation,” Blanche wrote, “are gone over by you with Dr. Jones I thought it most convenient that I [send] him my suggestions in order not to trouble you unduly.” What were those suggestions? Is there any way of knowing? We read that Blanche “personally edited every page of [James Reston’s] Prelude to Victory,” but nothing about what that process involved. How fascinating it would have been to learn how, and if, Blanche improved the novels of James M. Cain and Elizabeth Bowen, or the translations of André Gide and Simone de Beauvoir.

Ultimately, though, Claridge succeeds at what she has set out to do. The Lady with the Borzoi not only argues convincingly for the centrality of Blanche Knopf’s place in publishing history but makes it difficult to look at the Knopf logo without considering how closely the sleek Russian wolfhound reflects Blanche’s sense of herself and her public persona: streamlined, intelligent, elegant, and driven to run ahead of the pack.