1.

When Michael Hayden was a young air force officer in the 1980s, the military stationed him as an intelligence attaché in Bulgaria. There, the man who would rise to the top of the American intelligence community in the post–September 11 era lived under constant surveillance: he and his wife, believing their apartment to be bugged, kept toy erasable pads scattered around it so they could converse in writing. Against that tense cold war backdrop, Hayden was once talking with a political officer in the Bulgarian government and became frustrated, blurting out, “What is truth to you?” The Communist Party apparatchik supposedly answered, “Truth? Truth is what serves the Party.”

In his memoir Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terrorism, Hayden uses this anecdote to set the stage for a discussion of how intelligence officials are supposed to function in a modern democracy. Their crucial task, he writes, is to be “fact-based and see the world as it is,” supplying complete and accurate information to policymakers who make difficult decisions. His veneration of this ideal accords with his contempt for certain journalists he sees as “hopelessly agenda-driven” and with his self-image as a truth-teller. He observes that an entity that lives outside the law, as the Central Intelligence Agency does when it carries out covert operations abroad, must be “honest,” adding: “Especially with yourself. All the time.”

When intelligence officials live up to this standard for candor, the information they supply may be inconvenient for the various agendas of decision-makers. When President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney ran the country, Hayden’s CIA, he writes, told the White House that the insurgency in Iraq was spiraling into a sectarian civil war, and later that Iran had halted its nuclear weapons program. The latter assessment, which did not serve the purposes of hawks who wanted to escalate the confrontation with Iran, led many on the political right to conclude that the CIA was taking “revenge” on the Bush White House for “being forced to take the heat” for inaccurate intelligence about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction programs before the war. Hayden writes that such talk “made for a nice, tight story, but it just wasn’t true. The facts took us to our conclusions, not retribution or predisposition.” During the transition after Senator Barack Obama won the presidency, Hayden and other intelligence officials “would work to get access to him and then create as many of what we crudely called ‘aw, shit’ moments as possible.” This meant telling the president-elect

about the world as they saw it, not through the lens of campaign rhetoric, tracking polls, or the world as you wanted it to be. The “aw, shit” count simply reflected how many times they had been successful, as in “Aw shit, wish we hadn’t said that during that campaign stop in Buffalo.”

Hayden suggests that President Obama’s early decision to keep using “extraordinary rendition” transfers of detainees to other countries’ intelligence services, a counterterrorism practice that Bush critics had come to see as deliberately outsourcing torture—unfairly, he maintains—was a result of such briefings.

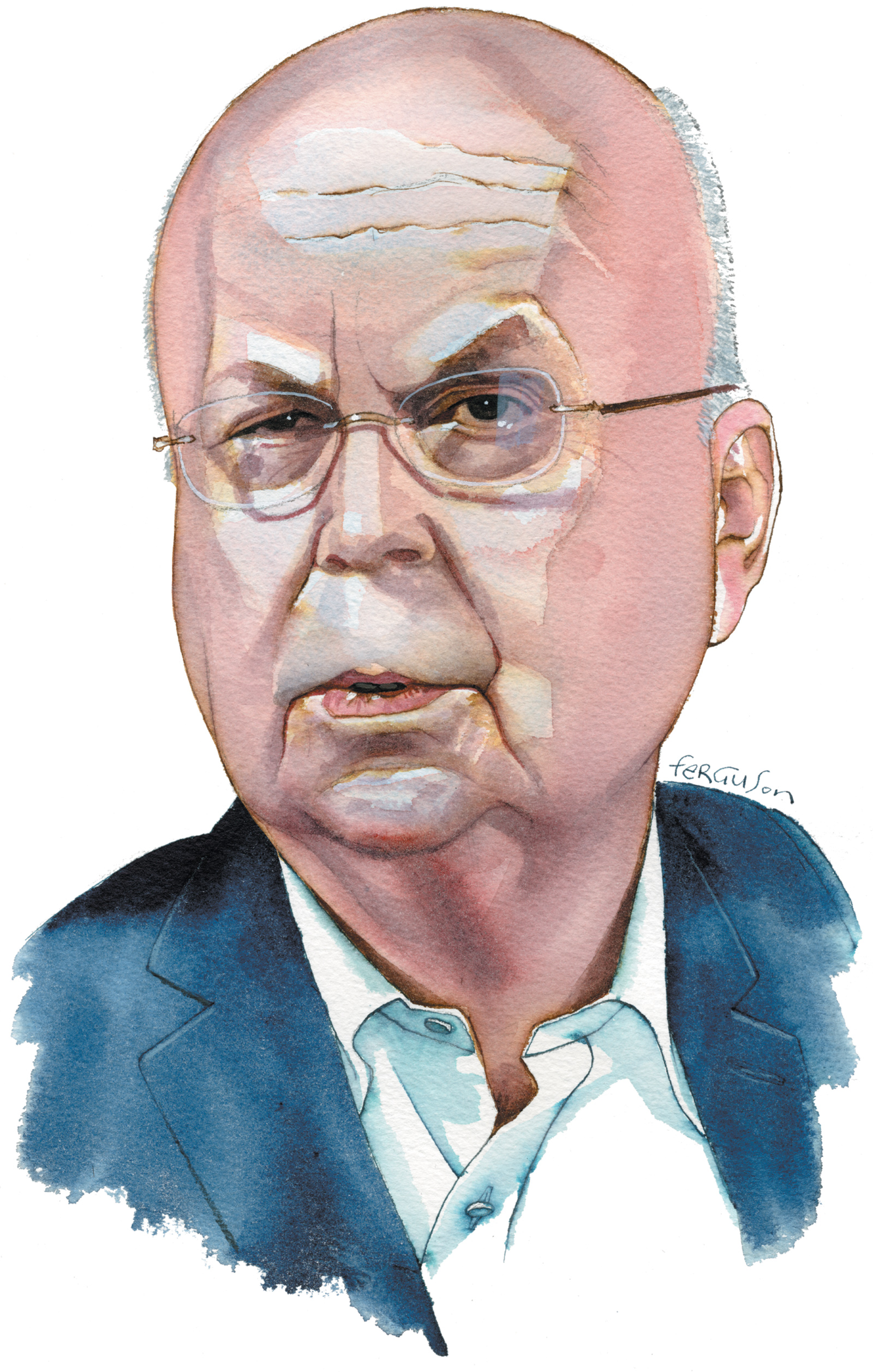

Hayden is good at projecting the impression that he is laying out everything you need to know about a complex topic. A quick-thinking, articulate, and gregarious man whose brains seem to be on the verge of bursting from his large forehead, he rose through the ranks of the military’s intelligence arm in part on his strength as a briefer. In 1999, the Clinton administration placed him in charge of the National Security Agency, the electronic surveillance powerhouse that was then struggling to keep pace with the explosive growth of the Internet.

Soon after the September 11 attacks, at Cheney’s invitation, Hayden proposed a secret NSA program to hunt for terrorists that came to be code-named Stellarwind—a set of warrantless surveillance and bulk data collection activities that appeared to be forbidden by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. The Bush-Cheney legal team, which embraced an idiosyncratically broad view of presidential power, produced secret memos endorsing Hayden’s ideas as lawful. The title of his memoir refers to one of his favorite metaphors: that in a dangerous world, intelligence agencies should aggressively play right up to the legal line dividing fair territory from foul—getting chalk dust on their cleats. He does not reflect on whether that axiom remains principled when the president hires referees who let him disregard the rulebook and redraw the foul lines wherever he wants.

In 2006, Bush appointed Hayden as the director of the CIA, which was then in turmoil over its program of holding terrorism suspects in secret overseas prisons and subjecting them to torture. He rejects that word, referring instead to “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which, as is well known from many public sources, included such methods as sleep deprivation for up to 180 hours, the suffocation technique known as waterboarding, confinement in a cramped box, shackling in painful stress positions, forced nudity, and water-dousing—often in combination. That program was largely over by the time he was in charge, but the previous period was emerging into greater light and he became arguably its foremost defender. He explained to Congress then, and now in his book, that such “enhanced” techniques were used not to directly “elicit information, but rather to move a detainee from defiance to cooperation by imposing on him a state of helplessness” so that he would, in theory, submit and talk freely to interrogators. After “on average a week or so” of such treatment, he writes, interrogations “resembled debriefings or conversations.”1

Advertisement

And in 2008, after briefing the Bush-Cheney White House that al-Qaeda was regenerating in tribal Pakistan and warning that “knowing what we know now, there will be no explaining our inaction after the next attack,” Hayden oversaw a sharp escalation of the CIA’s campaign of targeted killings using drone strikes, not only against known leaders but also in the form of “signature strikes” on al-Qaeda compounds.

In short, Hayden was a central participant in America’s three most controversial post–September 11 counterterrorism policies. And since 2009, when Obama decided not to keep him on as CIA director, Hayden has provided information to a different type of decision-maker: the American public, which has absorbed his take on the world via television appearances, opinion columns, and interviews. Now he has written his memoir “to show to the American people what their intelligence services actually do on their behalf.”

2.

Hayden sees intelligence agencies as subject to capricious political winds, with “political elites” complaining that security officials “have not done enough when they feel in danger and then complaining that they have done too much when they are feeling safe again.” There is reason to question whether he sometimes lets his defense of espionage agencies against such criticism—especially the latter type—interfere with his candor.

One example arose in November 2014, when the Senate was considering whether to pass the USA Freedom Act. The bill ended the NSA’s collection in bulk of Americans’ domestic calling records, under Section 215 of the Patriot Act, and replaced it with a new program that keeps the bulk data with the phone companies and requires the government to obtain a judge’s permission in order to query it. (Exposed by Edward Snowden’s leaks, the so-called 215 program was descended from part of the NSA’s Stellarwind, so among other things the bill amounted to an implicit rebuke of Hayden’s handiwork.) On the morning of the deciding vote, The Wall Street Journal published a column cowritten by Hayden that presented a dire assessment of the legislation, headlined: “NSA Reform That Only ISIS Could Love.” The Republican leader, Mitch McConnell, went to the Senate floor and urged senators to read it, echoing its arguments and entering it in the Congressional Record; later that day, Republican senators blocked the bill with a filibuster. But in June 2015, two weeks after the USA Freedom Act became law after all, Hayden suggested at an on-stage interview at a Wall Street Journal conference that he actually viewed its changes as trivial, saying:

If somebody would come up to me and say, “Look, Hayden, here’s the thing: This Snowden thing is going to be a nightmare for you guys for about two years. And when you get all done with it, what you’re going to be required to do is that little 215 program about American telephony metadata—and by the way, you can still have access to it, but you got to go to the court and get access to it from the companies, rather than keep it yourself”—I go: “And this is it after two years? Cool!”

In making this point, Hayden pinched his fingers together to emphasize how tiny the phone records program and the legislative changes to it had been.

Another example of his less-than-complete candor came to light in December 2014, when the Senate Intelligence Committee released a five-hundred-page summary of its study of millions of internal CIA documents about the interrogation program: it singled out Hayden with a thirty-seven-page appendix citing claims he had made in testimony before the committee and quoting documents that contradicted him. The report portrayed him as overstating the value of the information provided by detainees after they had been subjected to “enhanced” techniques, while understating both the number of people the agency had held and the severity of what interrogators did to them.

In his book, Hayden allows that he “may just have gotten some things wrong” while also denouncing the Senate report as “an unrelenting prosecutorial screed,” and quarreling with some of the accusations against him. For example, he writes, at the time he testified about the program in 2007, his purpose had been to talk about the “standard” way that interrogation worked and to explain its “current” status. The congressional staff investigators, he writes, had scoured millions of pages “to find the deviations, most of which were early in the program.” In March of this year, the staff for Senator Dianne Feinstein, the California Democrat who chaired the Intelligence Committee when it produced the torture report, issued a thirty-eight-page point-by-point rebuttal to Hayden’s memoir listing “factual errors and other problems” in his discussion of the interrogation program, accusing him of repeating his inaccurate testimony and of adding new distortions.2

Advertisement

In light of such episodes, a passage of Hayden’s book is striking: writing of the large amount of time he spent “talking about, explaining, and defending the agency’s record” on interrogations, he says that the motive for these efforts was partly

self-justification, not for me personally, but for the agency generally. Even though much of this had happened before I came on board, I felt duty bound to defend good people who had acted in good faith. In the world as it was seen from Langley, folks there believed they had done the right things morally, legally, and operationally.

But when it comes to matters that raise questions about the competence, reputation, and potential criminal liability of intelligence officials, “the world as it was seen from Langley” may not always be the same as “the world as it is.” If “truth” to that 1980s Bulgarian apparatchik meant whatever mix of fact and fiction that best served the Communist Party, truth to Hayden sometimes seems to be whatever serves the interests of his own faction: the permanent bureaucracy of intelligence and military professionals.

3.

The reader should know that Hayden disparages by name several journalists whom I respect and consider colleagues, and this may affect my view of him. I should also say that I have interviewed him and—while of course cross-referencing what he said with other sources—I appreciated his willingness to speak with me.3 Moreover, while I believe that major aspects of his book are flawed, I also think that other parts are excellent. Hayden spent his career grappling with some of the world’s most complex problems and he has many interesting, if often bleak, things to say about them—especially when his account is less driven by his concern to defend the record of the intelligence agencies.

For example, it’s fascinating to read an extended passage in which he describes flying around the world and meeting with counterparts from other countries’ intelligence agencies. It suggests the existence of an informal, global analogue to America’s permanent national security state. “We trade off each other for mutual benefit, even when there isn’t much agreement at the policy level between governments,” Hayden writes.

In fact, these partnerships are remarkably durable, operating below the surface, even when political relations are stormy. That’s because they enable mutually valuable exchanges between professionals who face common problems, between intelligence establishments that will still be in business and will still be expected to perform when policies and political leaders change.

Yet as he and fellow spy chiefs memorized each other’s family’s names and came to their counterparts’ homes for dinner or spent afternoons in their offices, there would often come a point where his opposite number would treat Hayden to some deep-seated “creation mythology,” breaking the flow of their rational conversation about the world. “That’s when something in the head of that professional across from you or on the phone is triggered and almost primordial judgments start to intrude on what had been to that point a fact-based dialogue,” such as the Serbian intelligence chief who maintained that Muslims do not care if their children die in war. When that happened, he writes, there was

little point in arguing. Just don’t agree or even seem to agree. Sit there, expressionless, not allowing yourself the almost instinctive head nod signaling “transmission acknowledged,” hoping that the episode passes quickly and you can get back to useful dialogue.

That was already remarkable, but then Hayden adds the following brilliant paragraph:

It took a while, but one night as I was preparing for an overnight hop to another destination on a foreign trip, the thought struck me. What of my side of these dialogues did our partners dismiss as American mythology? When I talked about self-determination? Cultural pluralism? The curative effect of elections? And when were my partners patiently waiting while I finished before we got back to “serious” talk? I never figured that out, but the longer I did this, the more certain I was that it had to be going on.

4.

Moments like that are why Playing to the Edge can be rewarding—if readers come to it already informed about the factual background. But reading this book is something like watching a movie with a lot of dialogue and plot twists while the sound is muted: if you have not previously seen the film, you will not really understand what happened. Hayden is generally too shrewd to say things that are outright false—the distortions in his book take the form of omissions, half-truths, misleading framings, and ambiguities that are subject to multiple interpretations. As someone who has spent years researching and writing about post–September 11 national security legal and policy controversies, I can only hope that readers will be sufficiently immersed in the details of that era to be equipped to spot Hayden’s spin.

Here are two representative examples of subtly misleading passages. First, Hayden recounts how he pressured editors at The New York Times in late 2004 and 2005 (well before I joined the paper) not to run a story about the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping, which the paper’s reporters had discovered; we now know that it was just one of the components of the NSA’s Stellarwind program, other aspects of which remained still submerged. Hayden assured a Times editor at that time that there was no disagreement within the administration over what the NSA was doing. But it later emerged that senior Justice Department officials had threatened to resign in March 2004 because they had strong legal objections to Stellarwind.

In his book, Hayden maintains that his assurance to the Times editors had been “true as far as it went.” His reasoning was that the objections expressed in March had been “settled” by then and “in any event involved an aspect of the program that was not part of the Times’s story.” That is, the crisis had involved the legality of a component of Stellarwind that collected, in bulk, metadata about e-mails. But Hayden’s statement that the legal objections made in March involved an aspect of the Stellarwind program that was different from the warrantless wiretapping component, while literally true, is misleading.4

In fact, Justice Department officials had strongly challenged the White House about more than one thing in the program. Hayden does not explain that until March 2004, the legitimacy of Stellarwind was based on a sweeping claim that presidents can lawfully override statutes for national security reasons, which among other things meant that the NSA could use the entire program to search for any international terrorist threat. As part of the crisis, the Justice Department officials had also forced the Bush White House to limit the NSA’s bypassing of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to the sole purpose of pursuing al-Qaeda. By narrowing Stellarwind’s scope, the administration could put the program on a firmer legal footing by linking it to Congress’s authorization to use military force against the perpetrators of the September 11 attacks.5 So the crisis had in fact involved as well the warrantless wiretapping that the Times had uncovered.

The second example showing how Hayden’s account can be subtly tricky begins with a chapter about the summer of 2006, when he took over as CIA director and worked on developing a scaled-back version of the detention and interrogation program amid, he writes, “outrage…at home and abroad,” set off by press reports about it. That chapter reaches a climax with a “magnificent” speech in which Bush announced that the CIA had transferred its remaining detainees to the military’s Guantánamo prison while he also defended interrogators’ use of an “alternative set of procedures” to elicit information that prevented attacks. Two chapters later, Hayden returns to the subject and writes that the Bush administration eventually approved keeping a narrower range of techniques available for interrogating future captives; he claims that Congress “had no impact on the shape of the CIA interrogation program going forward” because lawmakers “lacked the courage or the consensus to stop it, endorse it, or amend it.”

Several things about this are misleading, too. The first chapter, discussing Hayden’s summer of preoccupation with the program leading up to Bush’s speech, omits legal background that is crucial to understanding what was really happening—information that also puts a darker cloud over the CIA’s conduct. In particular, what Hayden does not say is that the Supreme Court issued a ruling about the Geneva Conventions that put American interrogators who had abused terrorism detainees at risk of prosecution for war crimes. In the crucial passage of Bush’s speech, which Hayden also omits, the president asked Congress to amend the War Crimes Act in order to curtail that risk. In implying that Congress was simply too feckless to specify which techniques should be kept, Hayden omits the fact that Congress voted in 2008 to limit CIA interrogators to the army field manual—thereby banning “enhanced” tactics like waterboarding and sleep deprivation—but Bush vetoed the bill.

While Hayden does eventually mention both that there had been a Supreme Court ruling about the Geneva Conventions (though he still avoids the phrase “war crimes”) and a vetoed bill about the army field manual, he notes those facts about forty and 130 pages, respectively, after his primary discussion of the material whose interpretation they would have altered if read in conjunction with those details. And he never mentions that the Senate report later found—and the CIA partially conceded—that the list of counterterrorism successes in Bush’s speech had been riddled with misinformation, such as attributing the discovery of new facts to the interrogation programs when that information actually derived from other sources.

Playing to the Edge has many such slippery moments. As they accumulate, the impression of the world left by the book distorts the world as it actually was.

5.

In a years-long public information campaign, defenders of the CIA’s use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” have insistently put forward a world in which those tactics were far more effective and less brutal than the CIA’s own contemporaneous records, unearthed by the Senate investigators, show. Meanwhile, many Americans have decided to support torture. Last spring, the Pew Research Center found that 73 percent of Republicans said that torturing people suspected of terrorism was justified, as did 46 percent of Democrats.6 A changing attitude can be traced through Republican presidential politics. Although Senator John McCain, the 2008 Republican presidential nominee, vehemently opposed torture and called waterboarding by that name, in 2012 Governor Mitt Romney pledged to bring back such “enhanced interrogation,” although he—like Hayden—insisted that such techniques were somehow not “torture.” In 2016 Donald Trump proudly endorses torture without evasive euphemism, promising to use waterboarding and a “hell of a lot worse,” not only because “torture works,” but because even “if it doesn’t work, they deserve it anyway.”7

Hayden’s purpose in defending the interrogation program has been retrospective—shielding the officials previously involved in it. As for the future, he maintains that the CIA is out of the “enhanced” interrogation business for good. In February, appearing on the HBO show Real Time with Bill Maher to promote his book, Hayden said he “would be incredibly concerned if a President Trump governed in a way that was consistent with the language that candidate Trump expressed during the campaign.”

“Like what?” Maher pressed.

“Well, uh, ‘we’re going to do waterboarding and a whole lot more—because they deserve it,’” he said, leaning forward to punctuate the distinction about motivation. Leaning back again he began to stammer. “Not be—you know—look, we did—we did tough stuff….”

But before Hayden could finish trying to reconcile his support for the defunct program with his opposition to Trump’s proposal to revive and expand it, Maher came to his rescue, interrupting with another controversial idea put forth by Trump: “What about killing the terrorists’ families? Oh my God, I mean, that never even occurred to you, right?”

“Oh God, no!” Hayden replied, and now clearly at ease again, told Maher that if a President Trump ordered such a war crime, the military would refuse to obey him.

The exchange made the news. But several weeks later, Alberto Mora, a former general counsel of the US Navy in the Bush administration who had objected to abusive military interrogations at Guantánamo,8 wrote that, in view of Hayden’s record, it was ironic for Hayden to be “sounding the alarm” about Trump’s talk of restoring torture. Hayden’s vigorous defense of the CIA’s past practices, Mora wrote, had “helped make torture cost-free to those who devised and inflicted it.” The United States’ failure to hold itself accountable for what happened, Mora said, “drains the crime of torture of its proper gravity,” eliminating the stigma of being pro-torture and encouraging those, like Trump, who wish to bring it back.9

Near the end of his memoir, Hayden tells the story of participating in a debate on privacy versus security. Afterward, as he was walking offstage, he did not turn as he heard a woman shout out, “You’re a liar, Hayden. You have blood on your hands.”

“I didn’t turn because I judged her to be unpersuadable,” he writes. “No sense trying. She had her world. The rest of us had ours. Or I, at least, had mine.”

-

1

Notwithstanding Hayden’s explanation of how such methods were used, Senate investigators found CIA records showing that in practice, its interrogators often began subjecting detainees to “enhanced” treatment immediately after taking custody of them—that is, before they had been questioned and demonstrated any defiant unwillingness to cooperate—and that the interrogators also asked questions while subjecting detainees to those techniques, not just afterward. For further discussion of the “state of helplessness” see the article by Tamsin Shaw describing the controversy over this condition and the correspondence that followed: “The Psychologists Take Power,” The New York Review, February 25, 2016; “Moral Psychology: An Exchange,” The New York Review, April 7, 2016; and “‘Learned Helplessness’ & Torture: An Exchange,” The New York Review, April 21, 2016. ↩

-

2

Vice Chairman Feinstein Staff Summary, “Factual Errors and Other Problems in ‘Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terror,’ by Michael V. Hayden,” March 2016, available at feinstein.senate.gov. ↩

-

3

For example, I quote Hayden in my recent book Power Wars: Inside Obama’s Post-9/11 Presidency (Little Brown, 2015). In Chapter Five I write about the until recently secret history of how NSA surveillance technology—and constraints upon it—evolved during the thirty years leading up to the Obama presidency, including the crucial years when Hayden was director. ↩

-

4

One major aspect of the controversy in March 2004 involved whether it was lawful for the NSA to gather bulk metadata about e-mails—data showing who is writing to whom and when, but not what they say—using devices installed on Internet switches without court orders. The Justice Department forced the White House to halt such gathering of information until that July, when a judge on the nation’s intelligence court accepted a secret and novel legal theory under which she had authority to issue such orders. Hayden’s book largely focuses on government access to telephone calls and never clearly explains how the collection of Internet communication and metadata—parts of which remain classified even though they are known—was in some respects more central to Stellarwind. ↩

-

5

Charlie Savage, Power Wars: Inside Obama’s Post-9/11 Presidency (Little, Brown, 2015), p. 191. ↩

-

6

Richard Wike, “Global Opinion Varies Widely on Use of Torture Against Suspected Terrorists,” Pew Research Center, February 9, 2016. ↩

-

7

Jenna Johnson, “Trump Says ‘Torture Works,’ Backs Waterboarding and ‘Much Worse,’” The Washington Post, February 17, 2016. ↩

-

8

See Charlie Savage, Takeover: The Return of the Imperial Presidency and the Subversion of American Democracy (Little, Brown, 2007), pp. 177–181, 189. ↩

-

9

Alberto Mora, “Is America on the Brink of Returning to Torture?,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 2016. ↩