1.

In his 2004 essay “Writing Gay,” Edmund White tells how his father, coming to see one of his plays, asks him beforehand, “‘What is it about—the usual?’ which was his way of referring to a gay theme.” His new novel, Our Young Man, is about “the usual,” from an Edmund White we’ve met before but are always happy revisiting—smart, worldly, erudite, well-connected, and funny, in this case writing about gay society in early 1980s New York as seen from the point of view of a newly arrived French male model. It’s a witty reversal of a reliable Jamesian formula White has used elsewhere—the naive American going to a sophisticated foreign place, often France, making endearing gaffes, his goodness and healthy frankness finally conquering the wily and scornful natives.

Here the protagonist is Guy Dumoulin, a beautiful and nice young man from the sticks—Clermont-Ferrand, an industrial city in the center of France. Visiting Paris at the age of seventeen, he is noticed for his beauty, and from there embarks on a career as a model, which soon takes him to New York. In America, he is a huge success, makes a lot of money, and finds that everyone wants to sleep with him.

One advantage of telling the story from Guy’s point of view is that it gives White a chance to comment on American society through the eyes of a detached and astonished foreigner: “Here in America folks appeared to be vulgarly friendly,” though you have to accommodate their “strange allergies and food dislikes.” He learns not to call servants servants: “Americans with their fussy egalitarianism preferred the word ‘help.’” Their main courses for some reason are called entrées, and they like music and candlelight in their restaurants, unlike the French.

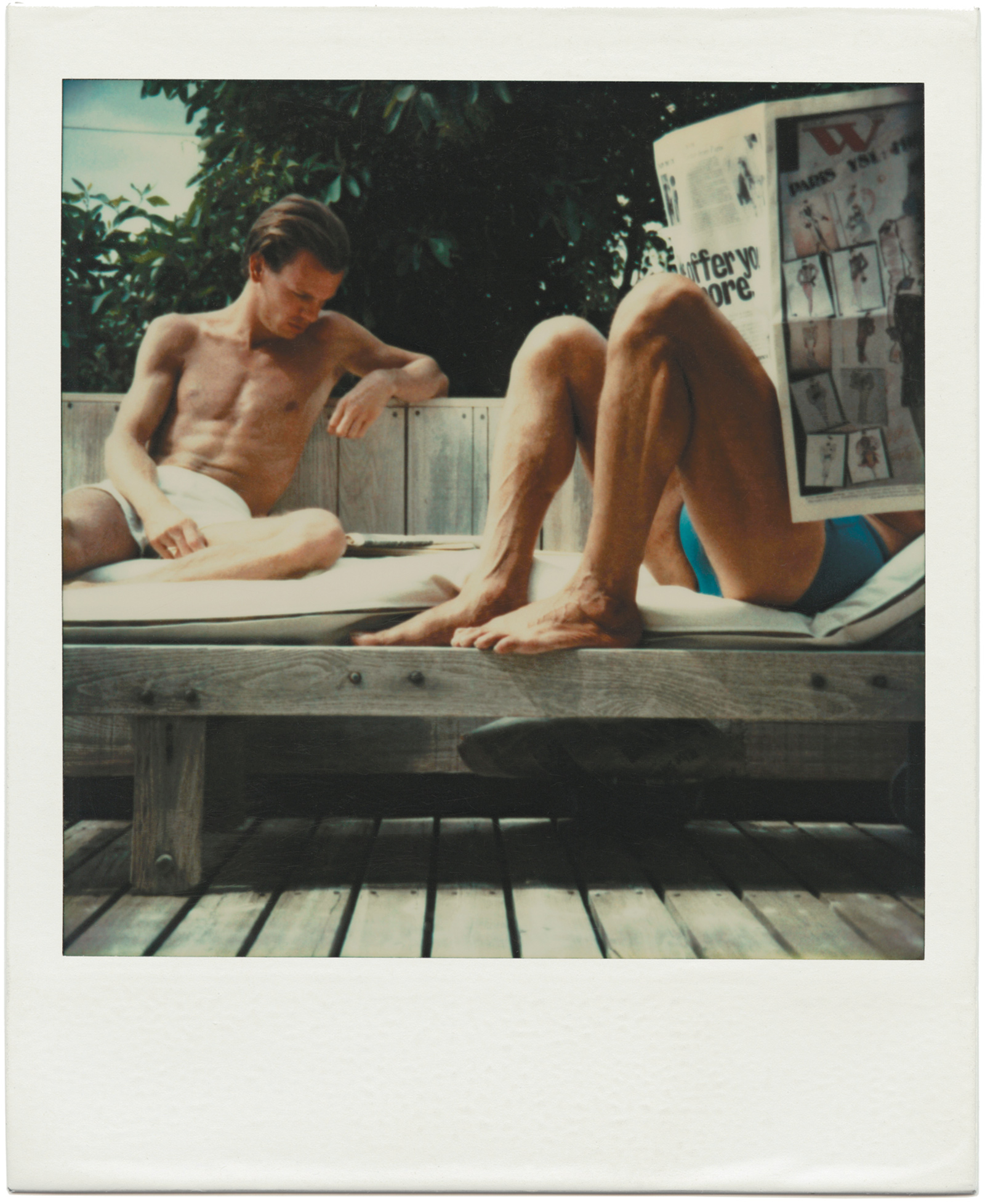

Most of the time, events are seen from Guy’s perspective, and he’s a fairly reliable narrator, “good at imagining things from another person’s point of view,” in this resembling the author; often Guy’s observations come to seem like White’s, who is a leading historian of the gay community. Looking at a group of revelers on Fire Island, “they’re drunk now,” he says,

and optimistic, but they will soon be squabbling over household expenses and hoping they’ll find love later in the Meat Rack. They’ll be arguing. “Why did you buy that expensive leg of lamb?” And they become especially cross at the beginning of September when they realize the summer is over and…they haven’t bagged a beau for the winter and they’ve maxed out their credit cards….

An American friend asks Guy if all French people are like him:

“So sure of your opinions? Americans are never that sure about what we think.”

“Yes, we have definite standards and we’re very confident about our taste. We learn at an early age what’s good and what’s bad.”

Guy notes that

American profs didn’t keep up to date but clung to the thinkers they’d known since they got tenure: Derrida, Foucault, Barthes…America was the attic of French culture….

Guy, sought after by everybody, is uncertain about his sexuality at first but soon decides he’s gay; White has dealt elsewhere with the process of coming to terms with one’s inclinations, most recently in his last novel, Jack Holmes and His Friend, and in his many autobiographical writings, beginning with A Boy’s Own Story and The Beautiful Room Is Empty in the 1980s. Guy, like Jack Holmes in the earlier novel, tries both men and women before deciding he is gay, but he is comparatively comfortable with his choice.

Another character, Guy’s friend Kevin, and his twin brother have “fooled around” together and each decides on an opposite sexual direction, Kevin gay and his brother straight. This note of volition more or less flies in the face of current orthodoxy that sexual preference is genetic or predetermined in some other inescapable way, but conforms to an orthodoxy of the 1950s, that homosexual tendencies were normal for everyone in adolescence but for most people were a phase and might modify or change. This idea is out of fashion now, with today’s almost political insistence on people coming out in grade school.

In Guy’s case, affirming his gayness doesn’t take him long, but it’s not a harmless choice, because it’s the early 1980s, in the first days of AIDS, when the mysterious syndrome was still called GRID, its etiology poorly understood, its prognosis inexorable. Novels are usually set a few years before the time they’re being written, when the writer has gained some distance from which to internalize and objectify the events of the earlier era. Much of the tension of the narrative comes from hindsight, our knowing what the characters don’t about that pitiless disease, and from our wish to save them, to shout “No, don’t do it! Or at least wear a condom.” Guy’s Fire Island set is still ignoring AIDS as far as possible, but one by one, people he knows begin disappearing.

Advertisement

For a decade after the early 1980s, in writing about a community shadowed by an unknown, fatal malady, a tragic tone was the only appropriate one; death was still the inevitable denouement, automatically dignifying each narrative where it appeared. But as Joshua Rothman put it in The New Yorker last September, writing about September 11 narratives, though “at first, a protective aura surrounds recent tragedies, preserving them from the injudicious meddling of pop culture,” time effaces such delicacy. Later discoveries and medical progress have liberated White, who has a gift for satire that was kept under wraps in such earlier works as The Beautiful Room Is Empty or the deeply felt and affecting A Married Man, about the harrowing death from AIDS of his French partner.

Happier times and the advent of triple antiretroviral therapy both free his inner satirist and allow him to view sympathetically the rationalizations and misinformation of the early days of the AIDS plague. “Anyway, we only did it once—and you need multiple exposures, don’t you?” Guy reassures himself about an older friend, Fred. In the present narrative, Fred, who has Kaposi’s sarcoma, bravely hopes “it wasn’t always linked to AIDS, it was something older Jews and Italians got just naturally, older Mediterranean men, but it used to be very rare…just in Jersey nursing homes or in Florida retirement villages.”

Another friend, the baron, says, “I believe this gay cancer only hits men who’ve had repeated venereal diseases. Their immune systems are compromised, overloaded. We’re in no danger….”

But this is not an AIDS novel, it’s a picaresque story of one person’s life and career, and a comedy of manners. Here are rich masochists, recently “out” middle-aged doctors, handsome waiters in short shorts and orange work boots, engaged in baroque scenes of license. The worldliness recalls Colette’s descriptions of fin-de-siècle and 1920s Paris. There’s also a lot of interesting detail here about the realities of a male model’s professional life, for which White thanks the writer Brad Gooch, a former model. White has an eye for characterizing detail—the brand of belt or fashionable shoes—(boxy Kenzo suit, lunch at La Côte Basque) and the same mondain understanding of the part these material items and chic locations play in signifying social rank or function. Guy goes to an orgy:

The other men were all of a type—tall, balding, skinny, pale, tattooed, almost as if they were vagrants who slept rough, smelling of old cigarettes and beer, their asses wrinkled and flat like deflated balloons but their dicks big and bridled with shiny cock rings.

This is at a New York S&M séance where the host, an elderly Belgian baron, plays the role of a bad dog and bites the legs of the guests before being beaten and humiliated by the people he has paid to do this, the effect of which is spoiled when the naive Guy dispels the illusions carefully cultivated by the thuggish hired actors by rushing to the baron’s side with an earnest, concerned query: “Ça va, Monsieur le Baron?” Because Pierre-Georges had told him that “humor was the great enemy of sadism,” after this, Guy often worried that he might inadvertently say something funny.

In the course of the narrative, Guy will have two significant love affairs, with Andrés, a Colombian student getting his doctorate in art history, who is sent to prison for forging and selling fake Salvador Dalí “originals,” and Kevin, the sweet twin from Minnesota with whom Guy takes up while Andrés is “away.” There are nods to French literature. With the good and naive Guy we think of Candide, and Guy’s relationship with Kevin makes us think of Colette’s Cheri, likewise a young beauty taken up by a solvent older lover.

White, though he is a scholar of French literature, and has written studies of Genet and Proust, among other French figures, remains a novelist in the English tradition, with an actual denouement where French dramas often just end without resolution.

2.

A reader who is not gay, reading novels about homosexual manners, can’t help but sympathize that gay people must have long been condemned to reading most of literature with a cooperative but intellectual, as opposed to instinctual, appreciation when it comes to the sex scenes. Things not in your category don’t translate into the same visceral understanding, it’s just information: Oh, is this what they do? We learn, for instance, that

Advertisement

men might style themselves as passive at first because it was easier to take it than give it, but that as a young man became self-assured in a relationship he became more assertive—the return of the repressed. So that both male partners in a couple end up as tops and look for the occasional bottom to fuck.

Across the great sensibility gaps that separate “men’s” novels from “women’s” novels, gay ones from straight, American from English, children’s from adult, and so on, there’s often a lack of information on either side, impediments to experiencing a literary work as it was meant to be understood by the unconscious mind, however much one may grasp it intellectually. About men, the female reader will have areas of ignorance, though women, perhaps especially, early strive for a kind of optional masculinity for the purposes of reading Conrad or Melville or the Hardy Boys. Doubtless we still can’t feel the archetypal affirmations of manliness, and necessarily have a very different take. Men less often make the effort to enter stories about women and girls—ask male friends if they’ve read Jane Eyre or even Pride and Prejudice and you’ll find a surprising number who haven’t.

So too for straight people with books in which the sex is gay, with its different rules and emphases. Of course there are poignant, often sad novels about gay people, like E.M. Forster’s Maurice, but is there a great gay erotic classic, a homosexual turn-on that straight people might read as they read the steamy scenes in D.H. Lawrence? Perhaps Ed White has written it, though I would guess his sense of mischief may have attenuated its power, humor being so fatal to the erotic, as we learn from Guy’s experience with the baron. What is the gay Fanny Hill? Who is the gay Maurice Girodias, or the gay Henry Miller? This is to say that there’s a lot of sex in White’s books, but all readers will not be able to respond in the same way.

Our Young Man is informative, wise, and amusing, and you can’t help wondering who the originals were, though you know, of course, that it’s only a novel. How does it end? It ends like life. Guy is getting older; his beauty will fade. His partner avoids sitting with the mirror behind him in hopes that Guy won’t notice his bald spot. Guy and Andrés could be Pip and Estella, or Jane and Rochester, or any other couple settling down, a happy ending at last possible, supplanting the tragic denouements of the 1980s.