The history of the American lighthouse is a history of calamity, insanity, and, in at least one case, cannibalism.

The Boon Island Lighthouse stands six miles off the coast of York, Maine, on a modest granite outcropping barely above sea level. For decades ships crossed the Atlantic only to founder here, nearly in sight of land. None had it worse than an English merchant ship called the Nottingham Galley, which ran aground during a nor’easter on December 11, 1710. The fourteen crew members hauled themselves from the wreck as their provisions, apart from three small rounds of cheese and a few old beef bones, sank into the ocean. After a week of starvation and sub-freezing temperatures, the resourceful men managed to construct a skiff from the ship’s debris. The captain and a crew member set off for the mainland in hope of salvation. Within minutes, however, a giant wave flung them back onto the island, demolishing the boat. “The horrors of such a situation,” the captain later said, were “impossible to describe.”

Those crew members who were not yet too weak to move now assembled a crude raft from the remaining scraps of wood. It departed safely from the island with two men on board. The raft even managed to reach the mainland a few days later. But the men did not.

The first fatality on the island was the ship carpenter, a “fat man, and naturally of a dull, heavy, phlegmatic disposition.” After what the captain later described as a period of “mature consideration”—not, it would appear, an especially long period—the men made the carpenter’s raw flesh into sandwiches, using seaweed for bread. They ate so ravenously that the captain had to ration the meat.

When the castaways were finally rescued on January 4 their story inspired calls to build the continent’s first lighthouse. But one was not built on Boon Island for almost a hundred years. As Eric Jay Dolin describes in Brilliant Beacons, his survey of American lighthouse history, this was a common pattern. Lighthouses may have come to be seen as brilliant beacons but they are also cenotaphs, marking deathtraps that for centuries devoured mariners along the continent’s coasts.

Only after enough maritime disasters occurred in a treacherous location was a lighthouse built. The nation’s first was completed in Boston Harbor in 1716, after the Massachusetts legislature found that the absence of a lighthouse “has been a great discouragement to navigation, by the loss of lives and estates of several of his majesty’s subjects.” A petition to build a lighthouse at Portland Head, at the edge of Casco Bay, was ignored until 1787, when a sloop crashed into it, killing two. “A long list of shipwrecks” led to the construction in 1761 of the first New York lighthouse, at Sandy Hook, and “the wrecks which lie plentifully scattered over the beach” off Cape Henlopen finally convinced Philadelphia’s merchants to build one two years later.

To do so, municipalities and colonies had to overcome the resistance of the so-called “wreckers.” Shipwrecks occurred with such regularity that the phenomenon created an entire underclass of scavengers who haunted the coast, waiting for the tide to deposit treasures. Nicknamed “mooncussers”—before lighthouses, a bright moon was a ship’s best navigational aide—wreckers were suspected of tying lights to cows and walking them along the beach, in imitation of ships’ lights, to draw sailors to their doom.

Brilliant Beacons is a comprehensive if flat-footed survey of a romantic subject, its many fascinating anecdotes alternating with flights of gratuitous detail. Dolin comes closest to articulating a thesis on the final page, when he ventures that “the success and growth of the American economy could not have been achieved without the help of these brilliant beacons.” It is true that, particularly during the country’s first century, the construction and operation of lighthouses were considered a major national security priority. George Washington signed the Lighthouse Act, which transferred control of lighthouses to the federal government, on August 7, 1789. It was the ninth law passed by Congress and the nation’s first public works program. During the Civil War, as in the Revolutionary War, armies on both sides destroyed lighthouses to disadvantage the enemy. The Confederacy was most aggressive of all, darkening or destroying 164 of its lighthouses, including one at Cape Hatteras, on the coast of North Carolina, reputed “the most dangerous stretch of coast in the country”; the extinguished light led to the destruction of forty Union navy ships and many more commercial vessels.

But the history of American lighthouses, like the history of any American institution, also reveals national qualities, particularly those that emerge under conditions of heightened pressure and extremity. The nation’s first keeper, George Worthylake, endured more than his share of pressure and extremity. He tended the lighthouse on Little Brewster Island, nine miles from Boston Harbor, living with his wife, five children, two slaves, a servant, and a flock of sheep. The sheep were the first casualties—fifty-nine of them swept into the ocean while Worthylake was busy stoking his lanterns during a storm.

Advertisement

Two years later, a boat returning Worthylake, his wife, and a daughter to the island capsized while one of his other daughters, Ann, watched helplessly in horror. The corpses of her parents and sister washed ashore over the next few hours but it was two days before Ann could sail to a nearby island for help to bury the bodies. A couple of weeks later two men who had been sent to replace the Worthylakes at the Boston Lighthouse also drowned in a storm. The lighthouse nearly burned down in 1720 and in 1753 and, because it was the tallest structure for miles, it occasionally burst into flames after being struck by lightning. Benjamin Franklin, who as a twelve-year-old had written a heavily circulated poem about the Worthylake tragedy, invented the lightning rod in 1749. Yet because of opposition from local clergymen—man should not dare “avert the stroke of heaven”—the lighthouse did not receive protection from God’s thunderbolts for more than two decades.

The earliest American lighthouses saved the lives of many sailors but often imperiled the lives of their keepers. Putting aside the risks of storms, lightning, and extreme isolation, a keeper had to maintain a constantly burning fire, fueled by highly combustible whale oil, many stories off the ground, inside a narrow, rickety wooden structure. This did not always go well. The whales of Nantucket had their revenge when the island’s first lighthouse burned to the ground because of an overturned lamp filled with whale blubber. Rhode Island’s first lighthouse suffered the same fate in 1753, four years after its construction.

In the 1780s, innovations in lamp and fuel technology made lighthouses safer, brighter, and more efficient—at least in Europe. While American travelers marveled at the startling superiority of British and French lighthouses, American lighthouses became a national embarrassment. This was largely due to the machinations of two men of low character and high bureaucratic standing. Winslow Lewis was a Cape Cod importer who was put out of business by President Jefferson’s Embargo of 1807, which prohibited American ships from sailing to foreign ports. Having been impressed by the quality of the Argand lamp, a lantern made with brass tubes invented by a Swiss physicist in 1782 and commonly used in European lighthouses, he patched together his own version. Lewis’s lamp was a second-rate bastardization, based on a weak grasp of optical principles, and providing less light. But Lewis secured a patent and aggressively marketed it to marine societies in New England. Ultimately the Treasury hired Lewis to install and maintain the lamps of every American lighthouse.

In 1820, after a series of bureaucratic reshufflings, oversight of lighthouses was given to one of the more obscure offices within the Treasury: the Fifth Auditor. The office was occupied by Stephen Pleasonton, the unlikely arch-villain of Dolin’s history. Like Winslow Lewis, Pleasonton knew nearly nothing about lighthouses or the science of illumination. He had been named Fifth Auditor by James Monroe, in return for an act of loyalty performed while serving at the State Department during the War of 1812. Fearing a British invasion of Washington, Secretary of State Monroe had ordered Pleasonton to smuggle the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, George Washington’s correspondence, and other historical papers out of the capitol. Pleasonton loaded the documents into inconspicuous linen bags and carried them thirty-five miles away to Leesburg, Virginia, where he locked them in an empty stone house. That night Washington burned and Pleasonton earned Monroe’s devotion.

Pleasonton deferred to Winslow Lewis on all matters pharological, particularly since Lewis was happy to underbid any potential competitors. Efforts by mariners and politicians to modernize America’s lighthouses only hardened the two men’s alliance.

Dolin recounts a series of increasingly urgent reform efforts, in which national experts called America’s lighthouses “the worst I ever saw in any part of the world” and “a reproach to this great country, feebly and inefficiently managed, and at the mercy of contractors.” Many European countries had long ago entrusted their lighthouses to engineers and scientists, most notably, in France, the prestigious Commission des Phares, composed of prominent engineers, naval officers, and hydrographers. By contrast, writes Dolin, “the United States had for the most part stuck with amateurs, and suffered the consequences.” But Pleasonton, hostile to any outside meddling, remained defiant.

Advertisement

Meanwhile European technology continued to progress. Pleasonton’s most egregious failure was his irrational opposition to the Fresnel lens, which Dolin, wearing his pharophilia on his sleeve, calls “quite simply one of the most useful and exquisite products of the Industrial Revolution, worthy of being considered not only technological masterpieces but also splendid works of art.” Invented in 1819 by the French engineer Augustin-Jean Fresnel, the lens replaced the reflectors then in use with a central glass panel surrounded by a series of concentric prisms. When the lenses enclosed a central lamp, Dolin writes, the apparatus resembled “a sparkling glass beehive.” The light produced by the lens was thirty-eight times brighter than that produced by the best British reflectors (which already far outpaced their American stepchildren), and required half as much oil.

Fearful of this new threat to his livelihood, Winslow Lewis convinced Pleasonton that the lenses were impossibly complicated and not worth the up-front expense. When pressed by members of Congress, Pleasonton appealed to their sense of American exceptionalism, doggedly declaring that America had the best and brightest lighthouses in the world. Dolin quotes lighthouse historian Francis Ross Holland Jr.: “One wonders how many ships that wrecked during Pleasonton’s thirty-two-year administration would have been saved had more effective lights been available.”

(It is one of the supplemental joys of Brilliant Beacons to discover the existence of a crowded field of lighthouse historians, most with names that seem plucked from Edith Wharton novels: Edward Rowe Snow, Fitz-Henry Smith Jr., Jeremy D’Entremont, Elinor De Wire, Mary Louise and J. Candace Clifford, Clifford Gallant. The lighthouse literature is no less robust, particularly at the regional level—Dolin cites Lighthouses of Texas, Lighthouses of the Upper Great Lakes, The Lighthouses of Hawaii—and extending to periodicals that remain in circulation to this day: Lighthouse Digest, Keeper’s Log, and the Lighthouse Service Bulletin.)

What shipwrecks and violent maritime deaths could not achieve, a fog in New York Harbor did. Pleasonton’s tyranny was at last shaken when a contingent of congressmen was briefly stranded on a steamboat in the harbor because of inadequate lighting. Their irritation motivated them in 1852 to pass a bill transferring oversight from Pleasonton to a federal Lighthouse Board, staffed by engineers, civil scientists, and military officers. By 1856 the board had built one hundred new lighthouses, bringing the national total to 425, and fitted nearly all of them with Fresnel lenses. Pleasonton, abruptly unemployed at seventy-six, begged old friends in the government for a new appointment. “To be turned out of office now,” he wrote to James Buchanan, “when I am too old to engage in any other business…would destroy me.” Pleasonton, for once, was right. Nobody hired him and he died two years later.

Dolin has read deeply in the lighthouse literature, perusing not only the histories but presidential lighthouse correspondence, lighthouse legislation, lighthouse engineering studies, lighthouse arcana. We learn the differences between geographic and luminous range, shoran and loran radar systems, and catoptric, dioptric, and catadioptric prisms. We read about variations in keeper salaries, the exact dimensions of dozens of lighthouses, and an account of a lunch that Calvin Coolidge had at the Devil’s Island Lighthouse during a Wisconsin vacation in 1928. Dolin’s pharomania infects the narrative, then it infects the prose: “Florida provided one of the few bright spots for the Lighthouse Board…” “America’s lighthouses, both literally and metaphorically, shone brighter than ever before…” and, in the final line: “They quite literally lit the way for the United States.”

The most vivid (illuminating) passages describe the solitary and often desolate lives of the keepers. The prospect of living expense-free in a gleaming tower by the sea would seem idyllic, conducive to reflection and profound thought. Albert Einstein thought so, suggesting that “young people who wish to think about scientific problems” work in lighthouses because “a quiet life stimulates the creative mind.” But the keeper’s life was not at all quiet. During periods of low visibility, keepers had to sound fog signals, which depending on the era might involve blasting cannons, shooting guns, ringing bells, or blowing horns. In 1887, the Point Reyes Lighthouse blasted a fog siren for 176 consecutive hours, causing its attendants to look, in the words of one journalist, “as if they had been on a protracted spree.” In 1906, after an automated bell broke during a fog in San Francisco Bay, the keeper Juliet Nichols beat it with a hammer twice every fifteen seconds, for twenty-four hours and thirty-five minutes, until the fog lifted. A mechanic repaired the bell the next day, but on the third day it broke again and Nichols again beat the bell through the night.

The government issued an instruction manual that, by 1918, was more than two hundred pages long. Keepers not only had to maintain the light and fog signals but also clean the lens, trim the lantern wicks, and scrub the walls, floors, windows, balconies, and railings, inside and outside. The many brass fixtures and appliances had to be polished diligently, a job that of itself was enough to drive keepers to madness, as evidenced by “Brasswork or the Lighthouse Keeper’s Lament,” a poem written in the 1920s by a keeper named Fred Morong:

O what is the bane of the lightkeeper’s life

That causes him worry, struggle and strife,

That makes him use cuss words, and beat his wife?

It’s Brasswork.

What makes him look ghastly consumptive and thin,

What robs him of health, of vigor and vim,

And cause despair and drives him to sin?

It’s Brasswork.

It continues in this manner for fourteen stanzas.

After the Lighthouse Board took over for Pleasonton, inspections were heightened and extended to the living quarters. Inspectors, writes Dolin, appeared without warning, wearing “white gloves to better detect dust and grime, and even went as far as running their fingers underneath the kitchen stove.” The rigorous surveillance appeared to have driven at least one keeper, Francis Malone of the Isle Royal Lighthouse in Lake Superior, into a frenzy of Stockholm syndrome, naming each of his twelve children after the district lighthouse inspector in the year of his or her birth. In a year that two inspectors showed up, Mrs. Malone gave birth to twins.

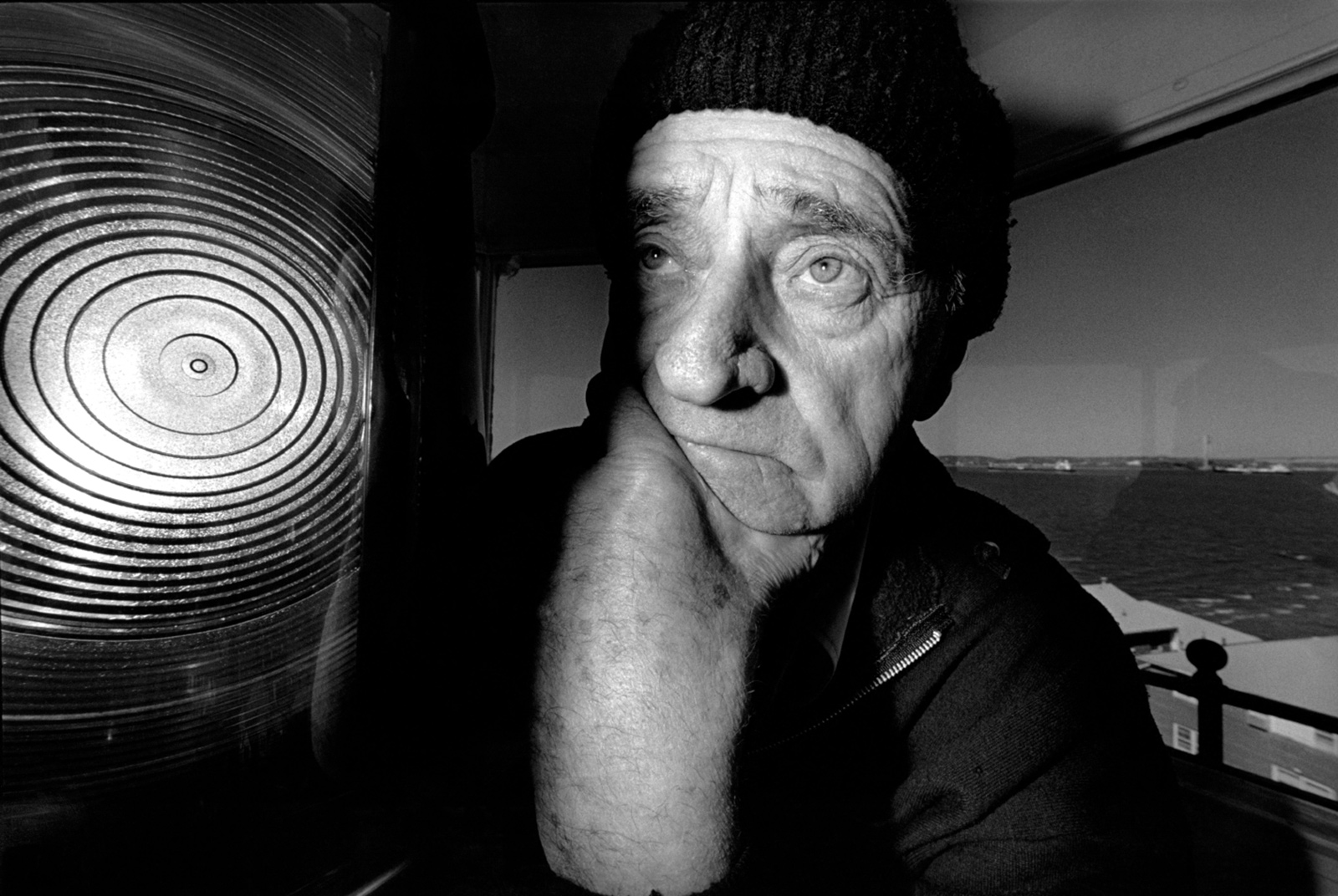

One can’t blame the Malones for trying to populate their solitary tower as quickly as possible. It was a reclusive existence, particularly in many of the sea-rock lighthouses, built to warn ships of hazards miles from shore, where keepers could leave the tower only by climbing down a ladder into a boat. “The trouble with our life out here is that we have too much time to think,” said a keeper of Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse, a slim granite tower rising 114 feet from the ocean two miles from the Massachusetts coast.

The Stannard Rock Lighthouse in Lake Superior, twenty-three miles from the nearest land, has been called “the loneliest place in America.” Dolin quotes a 1909 log entry by a keeper at the Cherrystone Bar Lighthouse, a hexagonal screwpile construction in Chesapeake Bay: “A man had just as well die and be done with the world at once as to spend his days here.” The entry was signed “All Alone.” But lighthouses on dry land were not much less remote from society. “Nothing ever happens up here,” said Nancy Rose, for forty-seven years the keeper of the Stony Point Lighthouse on the Hudson River. “One year is exactly like another, and except the weather nothing changes.”

No reader will hear Erika Eigen’s ukulele ditty “I Want to Marry a Lighthouse Keeper” in quite the same way after reading Dolin’s accounts of long-suffering keeper’s wives. The grimmest of these is the story of Nellie Smith of Conimicut Lighthouse, a spark-plug lighthouse set on a pile of rocks in the Providence River. After a brief trip to town, Mr. Smith returned to find Nellie and their two young sons poisoned by mercury bichloride. The older son was not yet dead, however, and the keeper continued to live with his son in the lighthouse. There is also the case of Mabel Small, crushed under her boathouse during the 1938 New England Hurricane. Despite “the shock of having witnessed the almost certain death of his wife,” writes Dolin, “Small managed to get back to the tower, where he kept the light burning and the fog signal going through the night.” “Almost certain” is the crucial detail, the suggestion being that Small chose lighthouse over wife.

When Kate Walker took residence in 1885 with her husband at the Robbins Reef Lighthouse in the middle of New York Harbor, she refused to unpack her bags. “The sight of water whichever way I look,” she said, “makes me lonesome and blue.” Five years later, her husband died; his dying words were “Mind the light, Katie.” She did for the next twenty-nine years. She grew so attached to her island tower, where time stood still, that she was overcome with anxiety on her rare visits to New York. “I am in fear from the time I leave the ferry-boat,” she said to a reporter in 1918. “The street-cars bewilder me. And I am afraid of the automobiles.”

The development of radar and radio beacons after World War II began to put keepers out of work and made some of the lighthouses obsolete. By 1990, all but the Boston Lighthouse had been automated with precision timers, light-activated switches, remote controls, fog sensors, and solar panels. Human beings were no longer needed. The last civilian keeper, Frank Schubert of the Coney Island Lighthouse, died in 2003 after spending the final fifteen years of his life fending off press attention “as if he were a rare exhibit in a zoo.” “Visitors, visitors, visitors—it drives me crazy,” he told an NPR reporter. “I don’t know why they like lighthouses…. To you it’s romantic, but when you see it every day, day after day, it’s not romantic anymore.”

In 2000 the Coast Guard began auctioning off that romance to the public. Some decommissioned lighthouses have been purchased by preservation groups. The Rose Island Lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island, supports itself by renting rooms to tourists who “pay for the privilege of being keeper,” doing chores and greeting guests. Other lighthouses have been bought by individuals for use as vacation homes. Sale prices have run from $10,000 (the Cleveland Harbor East Breakwater Lighthouse on Lake Erie, which during cold winters is entirely encased in ice) to $933,888 (the Graves Lighthouse in Boston Harbor, purchased by the owner of a special-effects company).

The privatization of lighthouses gives this American story its American ending. Our brilliant beacons, once symbols of audacity, progress, self-creation, defiant amateurism, civic-mindedness, and national glory, have assumed a different kind of symbolism altogether. To quote a recent real estate article in the Wall Street Journal: “One part unique retreat, one part folly, the private lighthouse may be the ultimate status symbol.”