Currently on view at the National Gallery of Art, a retrospective of the work of Hubert Robert is the first of this prolific, protean, and outstandingly inventive eighteenth-century artist to be mounted in America. It is a reduced version of the more comprehensive exhibition that was shown in Paris last spring under the title “Hubert Robert, 1733–1808: Un peintre visionnaire.”1 The greatest painter of antiquities in eighteenth-century Europe, Robert would likely have welcomed the spaces afforded him in both venues. In Paris, the exhibition was installed in the galleries underneath I.M. Pei’s pyramid at the Louvre—a museum whose Grand Gallery was redesigned in the mid-1940s in accordance with Robert’s ideas for lighting and display. In Washington, it is handsomely hung in the stately rooms of John Russell Pope’s neoclassical West Building, in a city whose public buildings abound in columns, peristyles, colonnades, and cupolas.

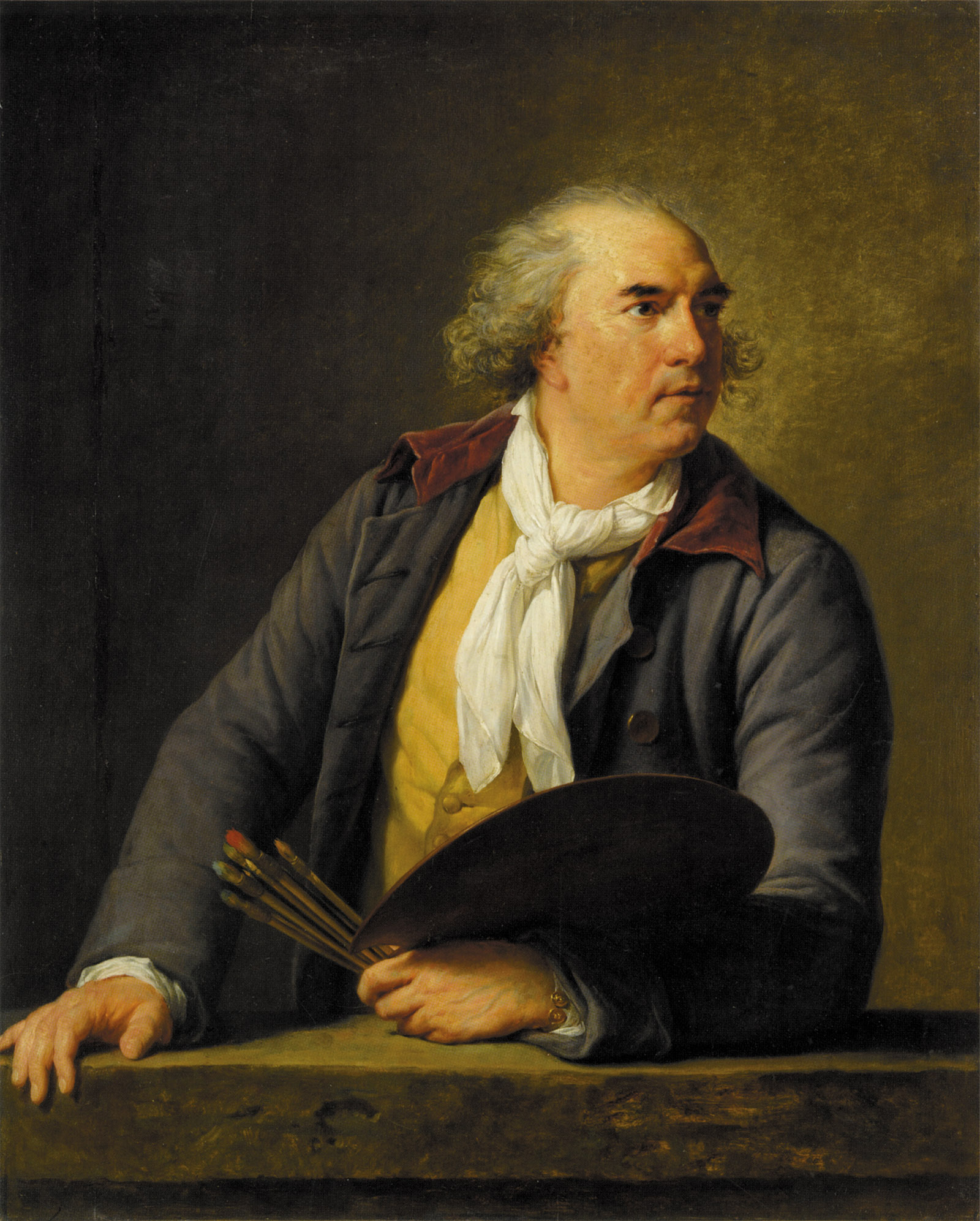

The exhibitions, and the catalogs that accompany them, distill Robert’s prodigious output in paintings, watercolors, and drawings made over nearly half a century. Like the older artist François Boucher, Robert is thought to have produced no fewer than one thousand paintings and as many as ten thousand drawings. His friend the portraitist Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun recalled that “he painted a picture as fast as he wrote a letter”; one of his protégés noted that he needed no more than one day to finish a large painting.

Robert’s paintings and drawings are to be found in most public collections, and they appear regularly at auction; but his facility and ubiquity have tended to diminish the regard in which he is held. Ingres acknowledged Robert’s talent but dismissed him as “only a decorator.”2 The Goncourt brothers, concerned to rehabilitate the art of the ancien régime, called him the “charming painter of witty ruins” but excluded him from their pantheon of artists.3 Renoir, by contrast, had little doubt of his stature. “That century which I adore produced great landscape artists,” he informed René Gimpel in April 1918. “I humbly consider not only that my art descends from Watteau, Fragonard, Hubert Robert, but even that I am one of them.”4

Robert was the best-educated and most-favored artist of the ancien régime. His parents were body servants in the household of François Joseph de Choiseul, marquis de Stainville (1700–1770), who came to Paris in 1726 as the envoy of the dukes of Lorraine and Bar at the court of Louis XV. In 1745, at the age of twelve, Robert entered the prestigious Collège de Navarre, founded in 1305, and for the next six years pursued a classical education there. He remained an able Latinist, translating Virgil with his patron, the bailli de Breteuil, in Rome in the early 1760s, and peppering his compositions with meticulous (and mostly accurate) quotations from the Roman authors.

Robert’s parents seem to have destined him for ecclesiastical office, but in 1751 he began an apprenticeship in the studio of the sculptor Michel-Ange Slodtz (1705–1764), also a designer of court festivals. Slodtz had lived and worked in Rome for more than seventeen years and must have imbued the young artist with a desire to go there. An opportunity presented itself in the autumn of 1754, when Robert, aged twenty-one, joined the retinue of Étienne François, comte de Stainville (1719–1785)—son of his parents’ employer and the future duc de Choiseul—who left for Rome to assume his post as French ambassador at the court of Pope Benedict XIV.

Thanks to Choiseul’s good offices and his agreement to cover expenses, against all the rules Robert was given room and board at the Palazzo Mancini, premises of the French Academy in Rome. His “infinite ardour” and talent “for painting architecture” won him the support of Charles Natoire (1700–1777), director of the academy, and, more importantly, of the latter’s superior in Paris, the directeur-général des Bâtiments du Roi, Abel-François Poisson de Vandières, marquis de Marigny (1727–1781). For nearly five years Robert was an unofficial pensionnaire at Choiseul’s expense, but his situation was regularized in August 1759 when he was granted official status at the French Academy. He remained a student there until February 1763, when he moved to nearby quarters in the Palazzo di Malta as a guest of the connoisseur and ambassador of the Order of Malta to the Holy See, Jacques-Laure le Tonnelier, bailli de Breteuil (1723–1785), whose hospitality continued until July 1765. Only then, after ten years and nine months in the Eternal City, did Robert return home to Paris.

Rome created Hubert Robert. For nearly eleven years, he immersed himself in the city’s piazzas, palaces, and ruins, familiarized himself with its classical and modern monuments, studied its antiquities wherever they were to be found, and haunted its environs in the company of well-born connoisseurs and fellow students. Energetic and intrepid, he engaged in daredevil feats such as scaling one of the arches of the Coliseum to place a cross there and exploring the labyrinthine passages of the catacombs by night (and getting lost in them).5 A hardworking student, he took instruction from Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691–1765), the foremost architectural painter in the city, who taught perspective at the academy, and he was conversant with Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s project to map the antiquities of the ancient world in virtuoso engravings and drawings, unsurpassed in their fantasy and technique. Piranesi was also a neighbor on the Corso, and the two artists traveled and sketched together on at least one occasion. To show his affiliation with these masters—and to assert his ambition to equal them, perhaps—the young artist italianized his name, signing many of his drawings of this period “Roberti” or “Roberti di Roma.”

Advertisement

It was principally in his red-chalk drawings, or “sanguines,” that Robert honed his craft. These drawings were made on laid paper of a more or less standard size, easily transported in portfolios; their fragile medium was stabilized (or “fixed”) by placing the drawing against a dampened sheet and running both through a press to create an offset, or counterproof. Robert thus doubled his production as a matter of course, and retained the mirror image for further use, consultation, or sale. He also filled over fifty sketchbooks and albums with drawings in crayon and pen and ink, which he retained throughout his life and to which he referred as his “promenades.”

Red-chalk drawings dominated Robert’s Roman production, and it is marvelous to follow him in these early years as he gains command of the medium, recording the sites, spaces, light, and movement of each scene as it is witnessed in situ and filtered through his imagination. These drawings evoke the harsh midday sun as it beats down upon stone and marble, dissolving over edifices of extraordinary solidity that dwarf a Lilliputian populace of ancient and modern Romans going about their business. Laundresses, dogs, and peasant families are favorite subjects, as are anonymous orators, pedestrians with enormous staffs on their shoulders, and genteel young draftsmen who have removed their tricornes and sit with their portfolios propped against their knees, absorbed in copying.

Affable, polished, and sociable—unlike his fellow student Fragonard, who would enjoy far less cordial relations with his patrons—Robert was able to travel beyond Rome and its environs thanks to the generosity of visitors such as the abbé de Saint-Non, who took him to Naples, Paestum, Pozzuoli, and Portici in the spring of 1760, and to Ronciglione and Caprarola the following year. In January 1763, Robert visited Florence in the company of his Maecenas, the bailli de Breteuil. Robert soon came to the attention of tastemakers in Paris as well. In 1760 the eminent connoisseur Pierre Jean Mariette (1694–1774) commissioned a pair of watercolors of celebrated Roman villas from him, executed in his most meticulous technique.

That same year Robert also encountered comte Anne-Philippe de Caylus (1692–1765), the powerful arbiter of the arts in Paris. In 1759, Caylus had commissioned another pensionnaire, the architect Victor Louis, to provide illustrations of unpublished antiquities for the latest volume of his Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises. Louis had simply extracted motifs from some of Robert’s imaginary drawings, fabricated the locations of these so-called discoveries, and added Greek inscriptions, provided by Robert. Had these illustrations been published, they would have made a laughingstock of Caylus. Robert had been unaware of Louis’s subterfuge, but was approached by the count’s Italian correspondent in the summer of 1760, who then informed Caylus that the young artist held him in great esteem and was ready to “draw all of Rome” for him. (Nothing would come of this commission.)6 The perils—and pleasures—of such fascination with antiquity were captured in Robert’s tender red-chalk drawing of two archaeologists at work at the Temple of Vespasian.

No institution was more invested in Robert’s early education and training than the royal office called the Bâtiments du Roi. In Paris, its director general, the marquis de Marigny, sought the opinion of his artistic adviser, the engraver and administrator Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790), whose advice he relayed to Robert in August 1759. Cochin approved of Robert drawing and sketching in nature, but urged him, for the authenticity of his lighting effects, to paint in situ as well:

However hard it may be to find a way of installing yourself appropriately so that you can paint and complete your pictures entirely from nature, an artist ardent for glory will find a way to do so.

An early reminiscence of Robert making his way through the Roman countryside, “his easel on his back, his box of colors in his hand,” suggests that he took Cochin’s advice to heart.

Advertisement

Robert left Rome for Paris at the end of July 1765 and one year later attended his first meeting of the Royal Academy, when he was received on the same day as both an associate and full member—a rare but not unprecedented distinction. As his reception piece he offered the stately and imposing Le port de Ripetta à Rome, a variant of the composition he had painted for the duc de Choiseul five years earlier, and executed in a style reminiscent of the esteemed French marine painter Joseph Vernet. Robert was received as a “painter of architecture,” one of the lesser genres in the academic hierarchy. Mariette described him as specializing in “Italian ruins and follies, enlivened by small figures and landscapes.” It is a measure of the liberalism of the fine arts administration, as well as testimony to Robert’s talent, efficiency, and charm, that during the next decade and a half this practitioner of a minor genre would accumulate offices, emoluments, and responsibilities normally reserved for the most distinguished history painters of the time.

Membership in the Royal Academy was required for an artist to exhibit at the Salon, held every two years during the late summer in the Louvre for about three weeks. This contemporary biennial—supported by the crown and by institutional and private lenders, and widely reviewed in the press—allowed academicians to show (and sell) their recent work. Robert made his first appearance at the Salon of 1767, where his submission of thirteen paintings and numerous sketches and drawings was rapturously received by the critics, with the philosophe Diderot prolix in his enthusiasms.

Thereafter Robert would send work to every Salon until 1802. He worked for a patrician clientele that included members of the royal family, princes of the church, ducs et pairs, nobility of the sword and robe, tax farmers, and bankers. His preferred genre for both small-scale or “cabinet paintings” as well as decorative ensembles—the latter often of considerable scale—was the “capriccio,” an imaginative amalgam of ancient and modern buildings, monuments, and figures, with little concern for historical, topographical, or chronological consistency. Robert allowed his patrons and clients a certain say in the subjects they acquired. He asked one collector to choose between architecture and landscapes, and between “drawings of my own composition” and “drawings made after nature in Italy.”7

After his return from Italy in 1765, Robert traveled extensively in France, extending his Roman repertory with sites from Paris and the Île de France, as well as those recorded on trips to Normandy, Languedoc, and Provence. While he was at times a keen and piquant observer of modern life and urbanization—he painted washerwomen on the Seine, the demolition of houses on the Pont Notre-Dame, the destruction of the Paris Opéra after the fire of 1781—his preferred subject remained the fanciful and poetic amalgam of monuments (and participants) that he had perfected in Rome.

The magisterial Monuments of Paris, painted in 1788, is exemplary of his approach. A host of immediately recognizable buildings are assembled with scant regard for their actual location. An elegant carriage enters the city through the Porte Saint-Denis, with the statue of Louis XIII astride a horse from the Place Royale in the center of the composition, and Goujon’s Fontaine des Innocents in Les Halles in shadow at right. Perrault’s colonnade of the Louvre occupies most of the background, surmounted by Soufflot’s new church of Sainte-Geneviève and extended, at right, by Bouchardon’s Fontaine de Grenelle, completed in 1745. Stonecutters and masons in modern dress are hard at work, and are impervious to the trio of gesturing, toga-wearing figures nearby. Orderly, limpid, and harmonious, Robert’s composition transplants the heroic architecture of Paris, past and present, to the open spaces and rugged terrain of the Campo Vaccino in Rome, indelible for him even at a distance of more than twenty years.

In the 1770s and 1780s, Robert added several administrative responsibilities to his thriving practice. He was named keeper of the king’s pictures, keeper of the Royal Museum, and councillor of the academy. He assumed responsibility for projects as both architect and garden designer, working for the crown at Versailles, Rambouillet, and Meudon, and for private clients at Ermenonville, La Roche-Guyon, and most notably at Méréville, where after 1786 he managed every aspect of the embellishment of the château and four-hundred-acre estate belonging to the court banker Jean-Joseph Delaborde. Between 1767 and 1776 Robert participated regularly in mondain gatherings such as Madame Geoffrin’s Monday salons and the drawing academy established by the duchesse de Chabot for her aristocratic friends.

Yet above all, he continued to produce outstanding monumental decorations for royal and private patrons. Among his most magnificent and majestic ensembles were the series of four paintings representing the “Principal Monuments of France” commissioned in 1786 for the dining room of the king’s petits appartements at Fontainebleau, exhibited at the Salon the following year, and never paid for. (These were on view in the Paris exhibition.)

In Washington a rotunda was created for the Art Institute of Chicago’s four monumental paintings of imaginary architectural ruins embellished by recognizable antique statues. These were made for Laborde’s salon d’hiver at Méréville, whose installation Robert oversaw in the summer of 1788. The consistency, fluency, and inventiveness of these large-scale canvases boggle the mind. Robert was a one-man factory, far more congenial than Andy Warhol but with the latter’s capacity for reinvention and the constant recycling of ideas and motifs. We know from Robert himself that he did not use studio assistants; his only collaborator was a certain Jean-Étienne Rey (1761–1834), who entered his service in the 1780s and who remained his homme de confiance until 1795.

Robert was a good friend of many of the first émigrés—he helped Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun escape from Paris on the night of October 6, 1789—but seems to have shared the confidence of many of his liberal patrons in the reforms promoted by the National Constituent Assembly. In 1791, however, Robert and his wife of twenty-four years, the admirable Anne-Gabrielle Soos (1745–1821)—with whom he had had four children, all lost in infancy—moved to Auteuil, on the western edge of the city, where they acquired and refurbished a house thought once to have been occupied by Molière. In March 1791 Robert refused Catherine the Great’s second invitation to come and work for her in Saint Petersburg. “One can only assume that Robert, whose principal talent is the painting of ruins, is like a pig in clover,” observed the empress’s adviser, Baron von Grimm. “Wherever he turns, he is surrounded by his favorite subject—the most beautiful and the freshest ruins in the world.”

As the Revolution progressed, Robert wisely kept his head down, but in October 1793, at the age of sixty, he was arrested for his “well-known lack of civic feeling and his liaisons with aristocrats.” Among those who signed his warrant was François Jean Baudouin, Boucher’s grandson. For three months Robert was imprisoned at Sainte-Pélagie before being transferred to the prison of Saint-Lazare in January 1794. He was released on August 4, 1794, a week after Robespierre’s fall, having experienced some of the harshest days of the Terror. Between July 23 and 26, 1794 (5 and 8 Thermidor an II), 165 prisoners from Saint-Lazare were taken to the guillotine; the carts that transported them arrived in the courtyard four hours before the names of the condemned were announced, leaving the prisoners in a cruel state of suspense. It must have been unbearable.

During his ten-month confinement, Robert painted at least fifty-three canvases, made a “prodigious” number of drawings and watercolors, and decorated some twenty plates with landscapes and scenes of prison life.8 Despite the sordid conditions and increasing danger, Robert left a body of work that is remarkably cheerful and uncomplaining, at times intensely poignant, and at times with a restraint and humanity worthy of Goya.

The mood of his watercolor of the Artist in His Cell is established by the epigram above the door that reads: “Carcer Socratis Domus Honoris” (The prison of Socrates is an honorable place). On the edge of the table at right is a quotation from Cicero, “Dum Spiro Spero” (As long as I breathe, I hope). Above the bed hangs a rare print after one of Robert’s own paintings, The Monuments of Rome, painted for the abbé Terray in 1777. A portfolio of drawings is propped against the table at right, and a large book—a Bible, perhaps—lies on its side on the shelf above. Immediately identifiable by his high forehead and long gray hair, Robert pauses in his reading as he stands to welcome the young jailer. We can still lead decent, normal lives, he seems to say.

Robert’s optimism at Sainte-Pélagie and Saint-Lazare was, in fact, consistent with the life-affirming sensibility that resonates throughout his oeuvre, in all media, on every scale. As his first biographer, the history painter Jean-Joseph Taillasson, noted in an obituary published two weeks after Robert’s death in 1808:

Robert’s coloring is silvery and harmonious, his touch light and rapid; everything in his painting is agreeable, always novel and picturesque. His animated brush revives those dilapidated walls, broken columns, and discarded capitals, which other artists, cold imitators, have portrayed as merely silent ruins. His genius has imbued them with expression, even eloquence. Furthermore, his paintings are nearly always enriched by groups of interesting figures that relieve the monotony and sadness inherent in such subjects, and communicate the sweet and happy philosophy that was so much a part of his character.

“The sweet and happy philosophy that was so much a part of his character.” This is a far cry from the melancholy and introspection that Robert’s ruin paintings induced in Diderot, who was moved by them to consider the ravages of time, the destruction of civilizations, and the imminence of death. With very rare exceptions, Robert painted nothing to excite in his audience “the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible”—the essential components of Edmund Burke’s theory of the sublime. Nor can he be said to have anticipated the “ruin sensibility” of the Romantics, which sought fulfillment in the “dark chasms of the mind and soul where catastrophic desires gape, uneasily and greedily, for fulfillment.”9

On the contrary, Robert is a witty and jovial witness of the classical and contemporary scene. His beloved statue of Marcus Aurelius serves as one end of a clothesline on which he has depicted the washing that has been hung to dry.10 The remnants of a Corinthian capital do duty as a makeshift desk, wide enough for a young man to lean on as he reads.11 Two fashionable Parisian women in fabulous hats sit happily among the ruins copying classical statues as a bearded patriarch and his companions look on aghast.12 And a statue of Hercules and Antaeus is transformed into a fountain as the god lifts his mortal opponent with such force that water gushes forth from his mouth.13 Robert’s vision of ancient and modern civilization, at times grand and dignified, at times affectionate and familiar, is always communicated with such brio and such joy.

-

1

The French version of the exhibition was organized by Guillaume Faroult and Catherine Voiriot. One hundred forty-four works are listed in the catalog, including a group of exceptional paintings from Russian museums that were embargoed for loan to the United States. That lavishly illustrated edition (Somogy Éditions d’Art/Louvre Éditions), at 543 pages, contains nine essays, fifteen thematic introductions to the entries for each work (or series of works), and an indispensable sixty-seven-page biographical chronology. The American version of the exhibition, overseen by Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Yuriko Jackall, is an altogether more distilled and elegant affair, with 102 works installed in six galleries. ↩

-

2

C. Gabillot, Hubert Robert et son temps (Paris, 1895), p. 56. ↩

-

3

In addition to Watteau, Chardin, Boucher, and Fragonard, the Goncourts devoted chapters to such petits-maîtres as Gravelot, Moreau le Jeune, Eisen, and Debucourt in their two-volume L’Art du dix-huitième siècle (Paris, 1873–1874). ↩

-

4

René Gimpel, Diary of an Art Dealer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), p. 21. ↩

-

5

Robert’s terrifying adventures in the catacombs were described at length in the fourth canto of the abbé Jacques Delille’s epic poem, L’Imagination: “Jaloux de tout connaître, un jeune amant des arts/L’amour de ses parents, l’espoir de la peinture,/Brûlait de visiter cette demeure obscure,/De notre antique foi vénérable berceau.” Jacques Delille, L’Imagination, Poëme (Paris, 1806), pp. 236–241. ↩

-

6

Robert was recommended by the Theatine cleric and antiquarian Father Paolo Maria Paciaudi, who, on July 23, 1760, offered to accompany him on any trip he might undertake for the count, “to observe, measure and draw.” C. Nisard, Correspondance inédite du comte de Caylus avec le Père Paciaudi, théatin (1757–1765), 2 vols (Paris, 1877), Vol. 1, pp. 196–198. Although Caylus did not commission Robert to design the frontispiece for the fourth volume of his Recueil, as Paciaudi had suggested, he included his illustration of a bust of a young man on plate LXXI, in the next volume, referring to him as an artist “whose technique and intelligence can easily seduce us.” Caylus catalogued the image as “a little piece that appears to honor the ancient Roman painters, or perhaps Robert himself”; see Caylus, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises, Vol. 5 (Paris, 1762), pp. 201–202, and plate LXXI. ↩

-

7

The collector in question was the diplomat and friend of Voltaire, Pierre-Michel Hennin (1728–1807), French resident in Geneva between 1765–1777. ↩

-

8

Étienne Vigée, the playwright and younger brother of the portraitist Vigée Le Brun, claimed that these plates were the very utensils “on which they brought him his dinner.” According to Gabillot, Hubert Robert et son temps, p. 198, Robert sold them for a louis—twenty-four livres—each. ↩

-

9

Rose Macaulay, Pleasure of Ruins (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1953), p. 5. ↩

-

10

Antique Capriccio with the Statue of Marcus Aurelius, 1784, oil on canvas, Paris, Musée du Louvre (on deposit at the Embassy of France, London). Catalog No. 64 (US edition). ↩

-

11

Young Man Reading, Leaning on a Corinthian Capital, circa 1762–1765, red chalk, Quimper, Musée des Beaux-Arts. Catalog No. 52 (French edition). ↩

-

12

Two Young Women Drawing in a Site of Ancient Ruins, 1786, pen and ink over black chalk, and watercolor, Paris, Musée du Louvre, Department of Graphic Arts. Catalog No. 61 (French edition). ↩

-

13

Capriccio with the Portico of the Pantheon and a Statue of Hercules and Antaeus, 1770, pen and ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor and white gouache, Vienna, Albertina. Catalog No. 56 (US edition). ↩