Some writers prompt us to respond in kind, to reply—speaking out loud to the page, or scribbling notes, or, if we are writers ourselves, riding the energy of the words we have read to make our own. Among poets, surely Walt Whitman has always been one of those prompters—for good and ill—to his enthusiasts. Not only is it almost impossible to read Whitman quietly to oneself; as well as declaiming him about the house, or reading him aloud in a group, writers and would-be writers almost always leave a session with Whitman by running to the page or screen or soapbox to spew. And although Whitman’s specifically King James Bible cadences have been taken up by only a few poets, most notably Allen Ginsburg, his covering-the-page tidal-wave poetics set their own broad style for American poetry, a wall-of-words (like pop music’s “wall-of-sound”) mode that has carried forward through such otherwise disparate and magnificent poets as T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, Charles Olson, A.R. Ammons, and John Ashbery.

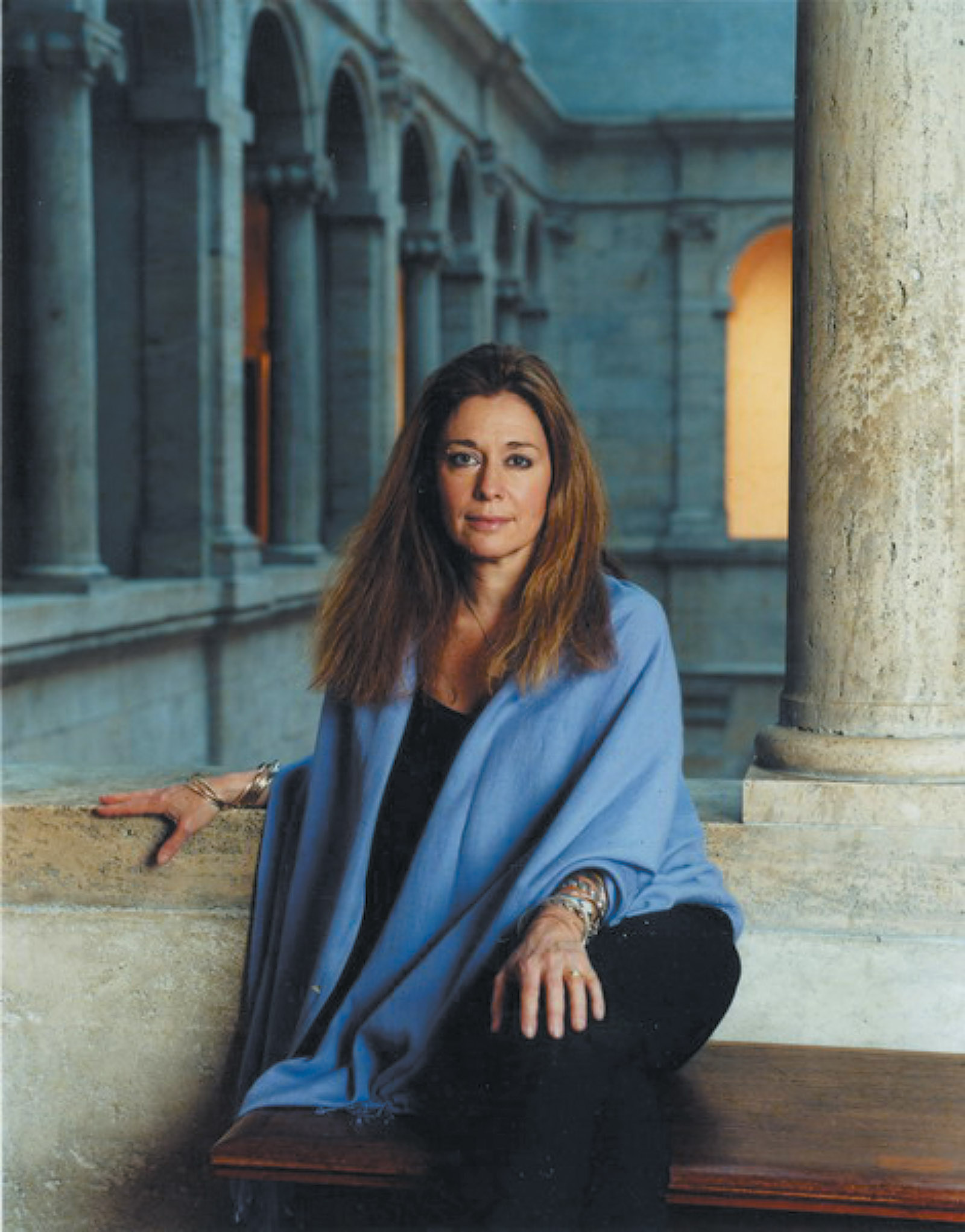

Jorie Graham has been producing her own powerful wall-of-words poems for several decades now. But unlike many of her fellow garrulous poets, Graham does not tend to incite her readers into their own words of response. Rather, her gorgeous, dense poetry more frequently works as a preemptive force, stunning her readers—this reader, anyway—into a deep and interior silence. So for me it is almost a betrayal of the experience of reading Graham to write about the work, a paradox indeed.

But the interiority she inspires is worth dwelling on: like incantations, her best poems cast spells that enforce rapt readerly attention to the speaker’s interiority, and then in turn call up a shared sense of privacy. Whether Graham is writing about a philosophical/metaphysical problem, as she often is (concerning materiality, or what can be known, or time), or politics (particularly, of late, the fate of the natural world), her childhood, or simply, as so many lyric poets have, describing the items in the local natural landscape—she dramatizes the mind, her mind, in movement over the problem, the memory, the landscape. And that drama—the drama of the mind in motion—is what holds our attention.

Her new collection, From the New World: Poems 1976–2014, is arranged chronologically. The opening poem is a very early one, “Tennessee June”:

This is the heat that seeks the flaw in everything

and loves the flaw.

Nothing is heavier than its spirit,

nothing more landlocked than the body within it.

Its daylilies grow overnight, our lawns

bare, then falsely gay, then bare again. Imagine

your mind wandering without its logic,

your body the sides of a riverbed giving in.

In it, no world can survive

having more than its neighbors;

in it, the pressure to become forever less is the pressure

to take forevermore

to get there. Oh

let it touch you.

The porch is sharply lit—little box of the body—

and the hammock swings out easily over its edge….

As should be apparent, Graham is not fundamentally an aphorist; her poems make sense best when one can read her work in extended passages such as these. Here, in this very early poem, we see the hallmarks of her mature style: a casually vatic voice, capable of uttering mysterious physical and ethical truths, some of which may also be sardonic social commentary (“your body the sides of a riverbed giving in./In it, no world can survive/having more than its neighbors”); a precise management of the line in all its rhetorical possibilities; and a mind in movement, restless but purposeful, relentlessly exact, considering the facts of the world.

This selection of poems, which includes some new ones, previously uncollected, offers an expanded and differently focused version of the poet than her Dream of the Unified Field selection did in 1995. That collection emphasized the poet’s philosophical concerns; here, although many of those same poems are included, the focus is more explicitly timely, social, and to some extent political. My guess is that Graham has looked over her work specifically to plumb what she has meant by “the new world” (from a title of another early poem). Our new world is a fraught one, as she makes clear in “Guantánamo” (“…grasp it, grasp/this, there is no law, you are not open to/prosecution, look all you’d like, it will squirm for you, there, in this rising light, protected/from consequence, making you a/ghost”), alongside poems that meditate on World War II, on the poet’s youthful involvement with the student demonstrations in Paris in 1968, and touching with a cool observing eye on a wide range of assorted public matters such as foreclosures, artificial intelligence, racism, and unemployment.

Advertisement

But the “new world,” as a term, resonates most here with nineteenth-century Transcendental excitement about America’s landscape and its spiritual and civic possibilities, which for Graham is undercut by an urgent concern for the fate of the earth we now experience sliding into heat and floods, the ruination of both the natural and the human worlds as a kind of horrible apotheosis of that dream of our ancestors. About a dozen poems here explicitly engage with climate change.*

That original poem, “From the New World” (first appearing in Region of Unlikeness, 1991), does not itself explicitly address ecological peril. It does, however, juxtapose two suggestive related stories that seized the poet. One concerns testimony from the 1987 trial of the Nazi concentration camp worker Ivan Demjanjuk about a girl who accidentally did not die in the gas chamber but emerged calling for her mother. The other concerns the poet’s experience of not being recognized by her own grandmother when she was dying, who

took me by the hand asking to be introduced.

And then no, you are not Jorie—but thank you for

saying you are. No. I’m sure. I know her you

see….

The poem circles these two stories, a private-public nightmare of annihilation connecting them:

You see it’s not the matter of her coming back out

alive, is it?

It’s the asking-for. The please.

Isn’t it?

Then the man standing up, the witness, screaming it’s him it’s him

I’m sure your Honor I’m sure….

In this poem, the “new world” from which the poet speaks is a place where the possibilities of implacable cruelty, and loss of the self, have become realities. How this metaphor, the “new world” of loss, extends to her present preoccupation with the destruction of our natural world is through our shared nightmare: that the end of the world we know is the great unfathomable loss of all self, personal mortality immeasurably compounded to include whatever future self we hoped to have through our descendants.

The 1950s and 1960s saw multiple poetic attempts to reckon with the prospect of nuclear annihilation of the species and the earth; the very best such poem I know, one of the great poems of the last century in fact, is Richard Wilbur’s “Advice to a Prophet.” Graham’s generation, and later ones, have always had that nuclear fear in mind—but have not written much about it directly. Global warming, on the other hand, has engaged the general poetic imagination—perhaps because its remedies are available, fairly obvious, and a matter of political will. So its advent is a slow-motion tragedy, and the attempt to describe it, as well as to forestall it if possible, seems a possible artistic enterprise. (Nuclear destruction has more in common with mythological fate; the instantaneous, perhaps even accidental, smashing of the world being a story it seems all must fear but no one could actually stop, the technology of the atom bomb not being something we can unlearn.)

This does not mean that poets write only about the obvious, or only with political intent; indeed, one could page or scroll through many journals today and read mostly lyric poems in their most personal, even introverted, manifestations. What makes Graham’s grappling with the political distinct, in this moment, is her unapologetic insistence that here the political is absolutely personal—that her reckoning with the destruction of the earth is also that reckoning with her own mortality.

Although she has little in common, aesthetically, with the identity poetry of many younger poets, she shares with them a desire to expand the lyric self to encompass the larger political landscape. Graham insists on the personal terror of annihilation that must agitate all of us as we contemplate ecological destruction. This comes through most directly in “Praying (Attempt of May 9 ’03)”:

…Please

don’t let us destroy

Your world. No the world. I know I know nothing. I know I

can’t use you like this. It feels better if I’m on

my knees, if my eyes are pressed shut so I can see

the other things, the tiniest ones. Which can still escape

us. Am I human. Please show me mercy. No please show

a way….

Later, in the same poem, the speaker offers herself up as an “instrument” to God, in the manner of Julian of Norwich, amid a description of the warming oceans:

…the

terrible bleaching occurring, the temperature, what

is a few degrees, how fine are we supposed

to be, I am your instrument if you would only use me, a

degree a fraction of a degree in the beautiful thin

water, flowing through, finding as it is meant to every

hollow, and going in, carrying its devastation in, but looking so

simple….

The position adopted here, the willingness of the poet to be of use, though doubtful any use can be made, is characteristic of Graham. And while one would hesitate to call Graham’s tone, even in prayer, humble, she displays no illusions about the efficacy of poetry to legislate, or moreover about the importance of her own acute feelings in the larger scheme; she is only doing what she must, enacting the drama of her mind and spirit grappling with what terrifies her, and us.

Advertisement

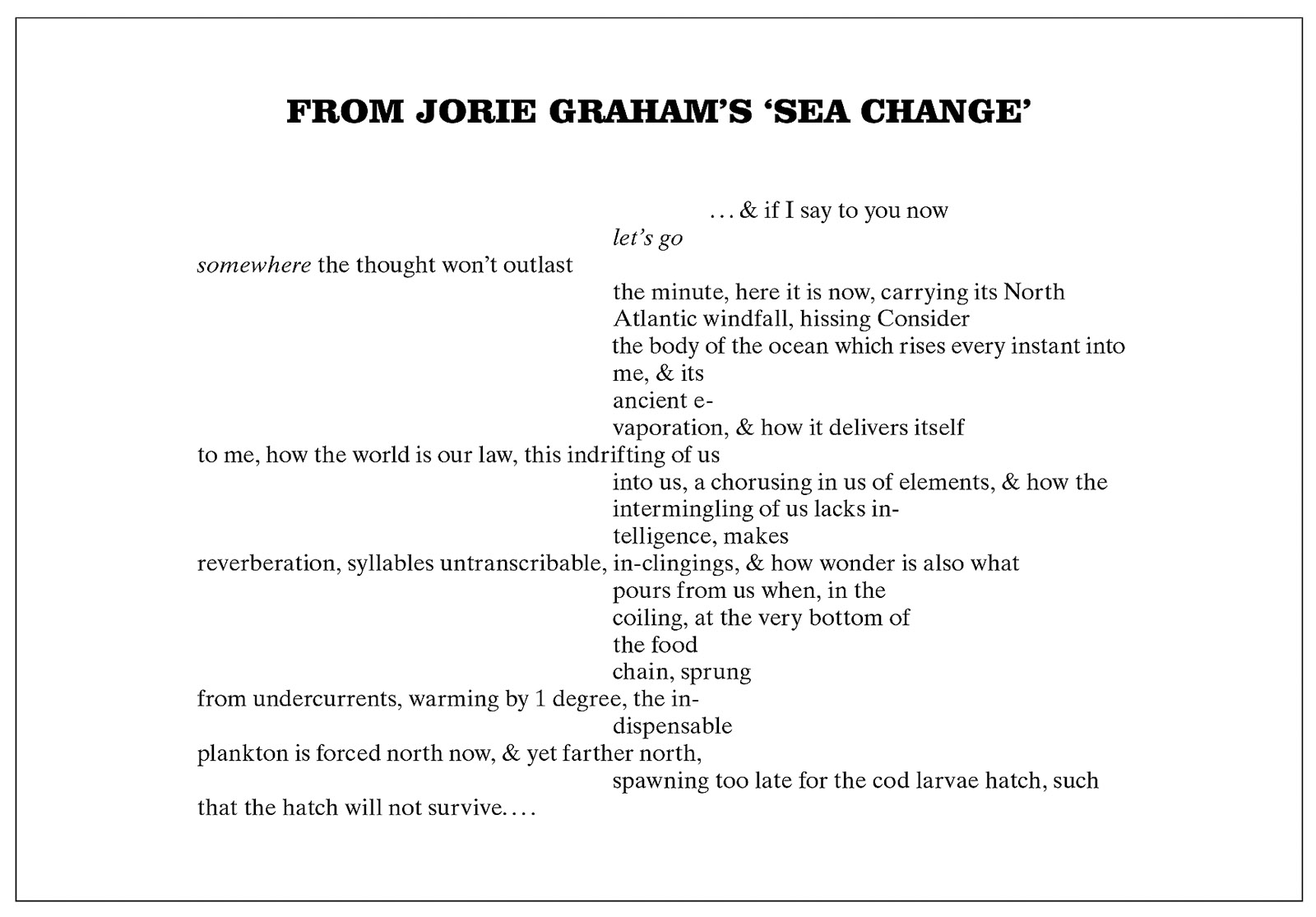

The volume Sea Change (2008) focused on ecological concerns; most of those poems are reproduced here, and they offer a center of gravity for From the New World. In these poems, Graham uses the page in a distinctive way: she splits it in two, and her often very long lines fan out like ribs on both sides of the center spine. Enjambments dominate; the resulting poetry looks like the passage from the title poem in the box that follows.

Another image suggested by this arrangement of text on the page is that of waves moving up and back on the sand; and there are other pictures the reader might make as well, of a mirror, a butterfly, a tree. Most suggestive to me, however, is not the image but the deliberate chaos created by the line breaks, highlighting the relationship between the apparent calculated rationality of the information delivered and the speaker’s helplessness in the face of larger forces.

In “Root End,” Graham speaks of “the desire to imagine/the future,” and in “The Violinist at the Window, 1918,” she projects herself into a Matisse painting, once again collapsing the past into the present but finding the future almost unbearable:

…I am standing in

my window, my

species is ill, the

end of the world can be imagined, minutes run away like the pattering of feet in summer

down the long

hall then out—…

Lyric poetry often functions as a kind of diary, although perhaps a veiled one. While much of Graham’s life evidently does not make it into her poems, this volume supplies the information of the poet’s cancer that colors the final poems in the collection. The illness of the species has become also the specific illness of the speaker; just as the mortality of the earth has also always been one with the mortality of the self. In the final poem here, Graham makes the direct connection between her cancer’s remission, the “little extra life to live now,” and some sort of possible posture for addressing the communal future—with a similar modest resolve to do what one can.

Yet in the service of describing something of what Graham does and says in her poems, it seems I have neglected to convey the beauty and the joy that her work also brings. I would describe it as a solemn beauty, even a harsh one. She is after all the standard-bearer of the enterprise of the high modernists; like Eliot, Pound, and Stevens she is an American-continental hybrid, and an aristocrat by temperament. She is no populist; the difficulty of her poems has been made much of, but this so-called problem is mostly a matter of entirely lucid poems that refuse to pander, that offer a sophisticated level of diction, allusion, and complexity of thought.

The most “difficult” poem in this volume, for instance, “Honeycomb,” contains prose passages that explicitly allude to and mimic the narrative style of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, and set a mood of fear (related to the poet’s experience of chemotherapy) against the consolations of memory and art. The “hive collapse” of honeybees, probably related to climate change, is the other dominant metaphor. The real difficulty that Graham sets before us is the difficulty of empathy; but her elegant, playful language, her urgent music, her austere but vulnerable appeal to her reader—all work to make that empathy possible:

…find the nearest flesh to my

flesh—>find the nearest rain,

also passion—>surveil this

void—>the smell of these

stalks and the moisture they

are drawing up—>in order not to

die

too fast. The die is

cast…. There is a page on my

desk in which first love is taking

place, there is a

page on my desk in which first

love is taking place again—

neither of the characters yet

knows they are in love—a few

inches from them Mrs Ramsay

speaks again—she always

speaks—and Lily Briscoe moves

the salt—…I tap this screen with

my fork—I dream a little dream

in which the fork is king—…

and the bees that did return to

the hive today—>those which

did not lose their way—>and

exactly what neural path the

neurotoxin took—>please

track disorientation—>count

death—>each death—>very

small….

As the poet skillfully, sensitively fingers the assorted objects, memories, and troubles of the personal, she reaches ever deeper and more broadly. Great art breaks your heart, as it must; as the feeling and intelligence of the poet’s self expands to embrace the world and the reader, we are made strong enough, perhaps, to live our “little extra life” more bravely.

-

*

One vexing term—vexing because imprecise—that has been used to characterize poetry engaged with this subject is “ecopoetics.” Only in rare cases, however, can I discern attempts by any poets to forge an actual “poetics,” or mechanics of the poetry itself, that matches form and content, so I prefer the simpler “ecopoetry”—if indeed any such term is needed at all. ↩