1.

Poverty in the West is suddenly, inescapably, around. It’s turning up as a deep problem here and there, even in electoral politics, and, clearly, dealing with poverty by the practice of ignoring it is reaching the limits of its usefulness. People at all levels are forced to deal with poverty in one way or another: in Paris recently I saw bands of distressingly shabby homeless people forming groups in front of monuments that tourists were attempting to photograph. They refused to get out of the way until they were given some money. And of course poverty and its cousins, inequality and corruption, are making their way into literature—as has been the case in earlier crisis periods of capitalism. Rafael Chirbes’s On the Edge is a novel for our time.

The 2008 financial crisis was particularly shattering in southern Europe. Its reach was broader there than elsewhere, its effect more instantaneous. On the Edge trenchantly explores the complex life of a young man who lived through Spain’s years of social catastrophe. The setting is the coast of Valencia, in the small towns of Olba and Misent, which lie across from the island of Ibiza.

On the Edge consists essentially of an unending soliloquy, a special case of the standard modernist stream-of-consciousness form. The main character’s soliloquy features an element of performance unlike the raw associative stream-of-consciousness usual in much fiction. Through the recollections of Esteban, the second son of a Communist furniture-maker and ex–political prisoner, we learn of lives that have been intimidated, weakened. In the telling, Esteban’s family, friends, and associates are brutally illuminated. (There are a few instances in which the author attaches soliloquys of other minds.)

The year is 2010—the direst year of the crisis, the year when economic, cultural, ecological, and moral failures came together. Esteban, in addition to running the small furniture factory founded by his father, is now caregiver to the mute, unresponsive invalid his father has become. A fine-grained appreciation of the complicated relationship between father and son emerges from the story. Esteban shares caregiving responsibilities with Liliana, a young Colombian migrant. This work is Gogolesque, but without Gogol’s humor. The conditions of life dramatized through Esteban include those of what might be called the nouveau pauvre classes as well as those of the growing population of the lumpenproletariat.

2.

In 2010 Esteban is seventy. He has never been married. The wood furniture factory is headed for bankruptcy, as is the construction firm into which he has sunk his father’s savings without his knowledge. Esteban has few interests, a social life limited to weekly card games at the Bar Castaner with a few old friends. He has serially fired his workers, the last one to go being his cousin Álvaro. He lacked the energy even to be a dilettante (briefly, like his father, he had wanted to be a sculptor). He lusts feebly toward Liliana but goes no further than soliciting the occasional hug or kiss on the cheek.

The family had been stigmatized by the victorious Falangists—the grandfather murdered by a Falangist mob in the post–civil war period; the father, a war veteran, imprisoned for three years. The consequences of the ancient defeat of the left reach deep into the present. There is a terrible overhanging tangle between the son and his father. On the Edge presents a year’s record of the acts and thoughts of the unhappy Esteban as he searches for some fit response to the grim dilemmas closing in on him.

At the metaphoric center of Esteban’s recitation is a natural feature of the coast near Misent—a wild area surrounding swamps and a saltwater lagoon. This place has been used by many, whether for hunting and fishing (it’s a supplementary source of food for the unemployed), or assignations with lovers or prostitutes, or in earlier times as a refuge for diehard defeated anti-Franco fighters—a temporary one, since the Republicans were incinerated in huge fires set by local Falangist thugs. Finally, the marshland has become a dump site for construction waste.

The lagoon is close to Esteban’s heart. He has hunted and fished there, and a significant part of his erotic life has occurred on its sands. He recognizes also that the very geological dynamics that created the lagoon will ultimately guarantee its disappearance. The lagoon plays a part in the final outcome of Esteban’s torn relationship with his father, and in his mind stands as an ultimate symbol of decline and fall:

When the wind from the Gulf of Lion is blowing hard and the waves get really big, the sea tries to recover what has been stolen from it by nature’s own sedimentary contributions and by human silt. The whole marsh was once a vast bay: the sea penetrated inland to form an arc that mirrored the one formed by the mountains, and the waves licked the foot of the mountainous amphitheater whose peaks I can see now above the reeds and beyond the cultivated areas that extend beyond the oxide-rich wetland.

In winter, the boundaries are clearer, unobscured by the greens of spring and summer: first, the ochers of the over-wintering reeds, then the dark green of the orange trees and, on the slopes, the very slightly lighter green of the pine trees; and above them, the bluish tones of the limestone. The bay has gradually been closing in on itself as the belt of dunes has grown higher and more extensive…. What engenders the marsh is also condemning it to extinction.

There is also a moral landscape through which Esteban must make his way. It fascinates and repels the reader. Esteban seems not to be agitated by the morally sordid characteristics of his pals and his family. They can be extreme. He becomes, for example, the silent partner in a firm whose sideline under Franco was disposing of the corpses of murdered Republicans. The situation is so unrelievedly appalling that the desire to know how such a miserable milieu came into being becomes a distraction. And one cannot say that Chirbes offers much enlightenment. After all, this is not a novel like Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin’s The Golovlyov Family, which is an extreme satire of a noble family of complete crooks and nitwits. Nor does he aim at creating a gallery of types intended to be appreciated in counterbalance to some virtuous cast of characters like the working class of old. If Chirbes were a vulgar Marxist, one might assume him to be characterizing neoliberalism as automatically producing a population of moral ciphers, but he is not a vulgar Marxist, not at all.

Advertisement

The origins of the ethical malaise of the community in On the Edge would, I assumed, be to some degree elucidated eventually. They aren’t. The cash nexus dominates to the very end. The radical weakness in human bonds affects Esteban in three social spheres.

Family ties: Esteban has very bad luck in his siblings. His older brother dies prematurely. His sister-in-law, formerly aggressively attentive to her in-laws, abruptly and permanently cuts all ties to the family. She keeps her children away from their grandparents, while finagling an arrangement to keep Esteban’s father paying the mortgage on her house. No explanations for this sort of thing are offered. Esteban’s sister Carmen marries and relocates to Barcelona. Esteban’s mother dies grieving because she has never been invited to visit her daughter’s home. Carmen’s children visit a few times, but relations cease altogether when Carmen fails to manage to her satisfaction the negotiations around an anticipated inheritance.

Esteban’s youngest brother is a professional con man who also appears after years of absence when the inheritance is under discussion. He attempts to have his Polish girlfriend seduce Esteban as an inducement in rigging the will. It doesn’t work. He vanishes forever. Esteban himself, as mentioned earlier, steals money from his father’s savings, which he invests with the son of a vile fascist family. About Esteban, it could be said that he is consistently more acted upon than acting on his own impulses. The embezzled money was genuinely if stupidly intended to make a profit for the family.

His friends: here the question is why the occupations, overt and covert, of his friends don’t offend him. They are a criminal lot. Justino, one of his three best friends, can stand for all of them:

He moves among the shadows of the night, where evil lurks and where his succubi have their beds, the laborers who stoke our nightmares with filthy coal. Justino covers up, dissembles, hides. His life is a mystery, you have to decipher the meaning slithering about beneath his words, he’s the oracle of all things murky, the sybil of the unsavory: he conceals the truth with lies and conceals lies with half-truths. You always have the feeling that he’s deceiving you…. He…fends off the tax people…but we all know that he leads a secret life and that, in the shadows, he lives far beyond his theoretical means….

I’m talking about land transactions, property transfers, estates registered in the name of nephews, brothers- and sisters-in-law, his retired mother- and father-in-law who both have Alzheimer’s…poor defenseless stooges whose signatures he has forged and who…would never dream they were the owners of apartments, business premises, import-export companies, orange groves and building sites like the ones they possess…underhand deals that you hear others mention only obliquely and sotto voce.

Others: the lumpen class is dangerous. Unemployed migrant workers turn reflexively to crime. Most of the Moroccans are tending toward jihadism and many of them praise the 2004 massacre at Atocha Station in Madrid.

Advertisement

The moral substrate of the narrative is rotten overall. In the case of Esteban’s family, their protracted experience as stigmatized losers in the Spanish civil war is of course a grievous burden. Esteban’s recollection of his father secretly and perilously following the events of World War II on the BBC and making notes on the progress of the Allied forces, which had to be hidden, is poignant. Still, the experiences of a class of families in the bad times before the end of Franco can’t fully explain the rot in Valencia.

The seemingly universal Hobbesian philosophy prevalent among the characters recurs in Esteban’s world: Ahmed Ouallahi, an ex-employee of Esteban’s, says, “All men are bastards… regardless of what God they believe in or say they believe in.” For Esteban’s uncle Ramón, “None of the men in this household…ever had any other religion than that of submitting to the codes imposed on them by nature.”

Probably the last place to look for some explanation of rot would be in culture—writing, polemic, ideology, religion, rogue memes—and no light breaks through from any of these. Esteban’s father is a devotee of the print culture of interwar Europe. He spends his spare time reading the classics. The family must keep his books buried to hide them from the Falangists. Then cable television takes over from print. Nobody reads, really. There are no references to periodicals or books. American music and films are universally popular. It’s the usual mixture, nothing special.

3.

On the Edge is a successful feat of experimental prose. It takes great confidence to repose the whole weight of a book on an essentially unbroken present-tense first-person stream of consciousness uncoiling over four hundred pages. There are a few little spurs of narrative off the main trunk, not many. Chirbes is bravely faithful to the shape that true internal discourse takes: when we are talking to ourselves, we tend not to give the last names of personages who are fully familiar to us, and when we rehear voices speaking to us as they did, we have no need to identify the speaker. So Chirbes, in an iron fidelity to the Joycean/early Faulknerian style he has chosen, omits to mention family names of his characters and inserts, without warning or identification, passages, some long, of the past speech of several characters. This requires the reader to be attentive and patient. Similarly, Chirbes limits the description of persons and places within the world he has created for them—a quintessentially modernist practice.

The one exception to Esteban’s descriptive frugality concerns the lagoon. The location is significant and precious to him and when he becomes lyrical about it, this makes aesthetic sense.

Finally, there is no plot in this book. Esteban’s year is a succession of the kinds of accidents of life that can befall us when we so consistently take the line of least resistance, as he has. The translation by Margaret Jull Costa is at her usual high standard. The sense that you are reading a translation passes quickly.

4.

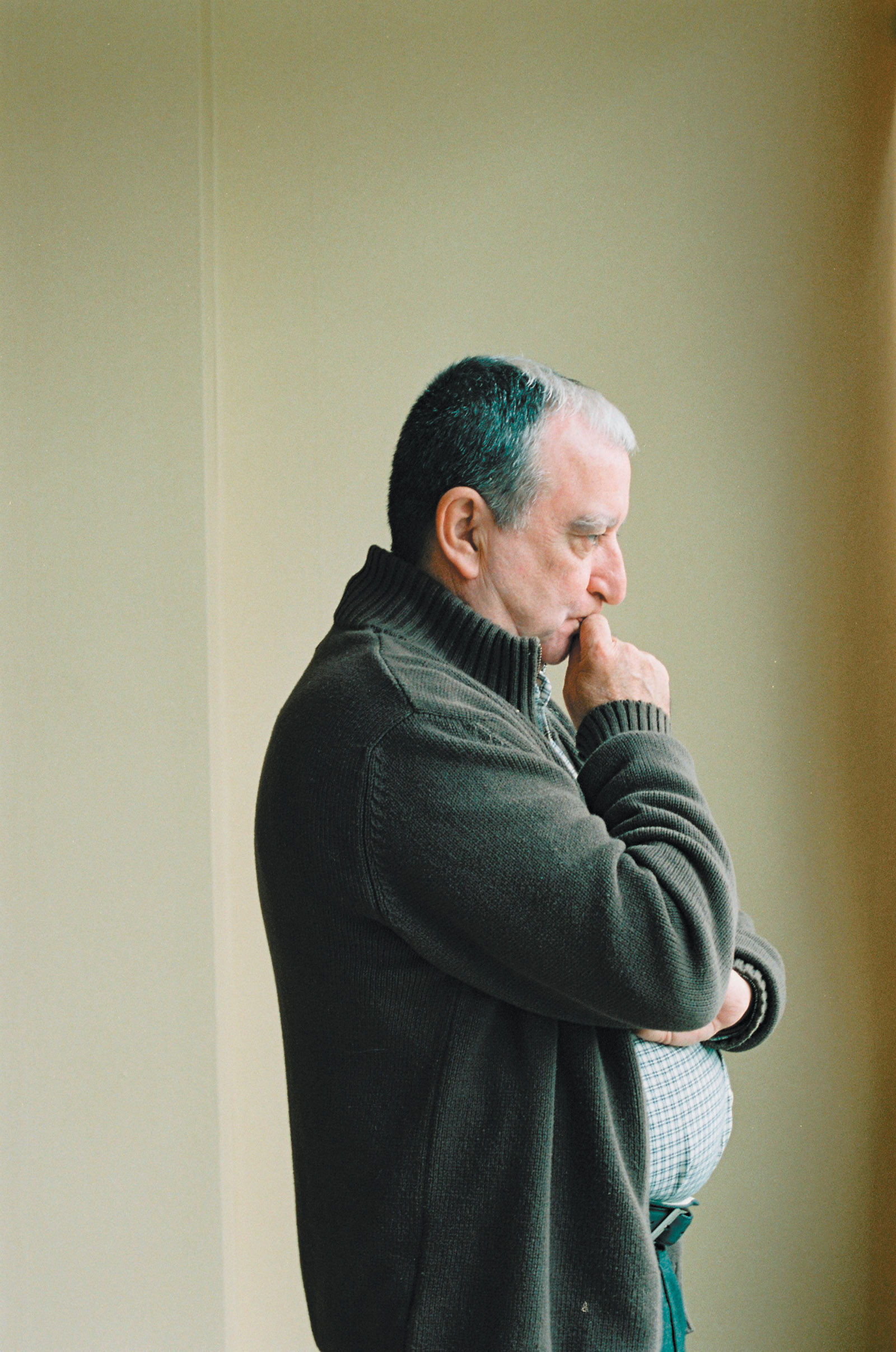

Rafael Chirbes is a writer new to me. He died last year at sixty-six, having in the last quarter of his vagarious life become an esteemed and greatly honored literary figure in Europe and Latin America. He is a densely powerful writer whose work can be daunting. When I commented to my wife that I was surprised at how little of his work has been translated into English, she half laughed and replied, “Well, this book, at least, seems to be a complete downer entirely about sociopaths, and it has no plot, and it’s long.” I hope in what I’ve written here I have contributed to forestalling a reaction like hers: a book written with art and force need not depend on pleasing subjects. In fact, the tension underlying art and often unhappy narratives can provide a confoundingly elevating aesthetic experience.

There are correspondences between the fictional life of Esteban and the actual life of the author. Chirbes was the son of Republican railway workers. Before that, his father had been a basket maker. While still young, he committed suicide. Chirbes’s mother was forced to turn over her eight-year-old son to an orphanage. Chirbes managed to go to college outside of Valencia. He did graduate work in history, and he entered writing through journalism. He was politically active, and was briefly imprisoned during the last days of the Franco regime. He began writing novels in the late 1980s.

A quip of Alexander Herzen’s came to my mind as I was reading Chirbes, a bleak assessment of life in Spain after Franco: “The Latin world does not like freedom, it only likes to sue for it; it sometimes finds the force for liberation, never for freedom.”

There are nine more novels and four books of essays still not translated into English. An early candidate for translation would seem to be the big trilogy on the Spanish civil war and the end of the Franco regime, which has been translated in Germany, where Chirbes has a strong popular following.

5.

In On the Edge Rafael Chirbes has set his characters to work against the background of two great spectacles. The foreground spectacle is the earth-shaking financial collapse of 2008. The accompanying background spectacle is of deep-rooted political disillusion. One spectacle is intensely topical. The other goes back to the 1930s. Periods of disillusion have given rise to some of the best novels in the modern canon—think of the disillusions of African independence, Russia under Stalin, post-Soviet Eastern Europe, India after the Raj, to name just four at random. In On the Edge I found something peculiarly gripping. When I finished it, I wanted to read it again to see whether there was something in it I’d missed.

I think it must be that the thematic conjunction of the topical and the damnably eternal is especially potent today. We don’t entirely comprehend 2008. Has there been a change in the way the neoliberal dispensation works? We are still measuring the consequences of that debacle, still trying to judge whether it’s over. Since 2008 the world has gone unsteady, and not only in the economic sense. Some academically respectable but apocalyptic readings of the crisis are in circulation. One is Wolfgang Streeck’s “How Will Capitalism End?” (New Left Review, May–June 2014). Streeck sees a destructive convergence of three fixed trends in late capitalism: a declining rate of economic growth, soaring overall indebtedness, and rising economic inequality in both income and wealth. His work interlocks with recent dark conclusions by Robert J. Gordon, Thomas Piketty, and Wendy Brown, among others.

With all its Valencian particularities, On the Edge resonates in a paradoxically bracing (because it’s clear-eyed), apposite way with today’s uncertainties and moods. On the Edge may work as powerfully as it does precisely because it is not a protest novel in the tradition of Zola’s Germinal, Sinclair’s The Jungle, Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle, or Hugo’s Les Misérables. There’s not a shred of hope here, or any emerging social force to which to appeal, and that feels about right.