1.

No urban design project in modern American experience has aroused such high expectations and intense scrutiny as the rebuilding of the World Trade Center site in New York City. It has taken fifteen years since the terrorist assault of September 11, 2001, for the principal structures of this sixteen-acre parcel in Lower Manhattan to be completed. In a field where time is money in a very direct sense (because of interest payments on the vast sums borrowed to finance big construction schemes), such a long gestation period usually signifies not judicious deliberation on the part of planners, developers, designers, engineers, and contractors, but rather economic, political, or bureaucratic problems that can impede a speedy and cost-efficient conclusion.

For example, in contrast to this slow-motion rollout, it took less than a decade to erect the Associated Architects’ twenty-two-acre, fourteen-building Rockefeller Center of 1930–1939, accomplished without benefit of the countless technological advances devised since then. That swiftness was owed in part to the project being underwritten by the richest family in America during the Great Depression, when jobs were scarce and both designers and laborers were grateful for work, but it was a logistical triumph nonetheless. With Ground Zero (the popular name for the site that emerged in the attack’s immediate aftermath), the lengthy delay reflected the project’s divided and ambiguous leadership as well as the political tenor of the times.

Who was really in charge of the undertaking remained a persistent and vexing question. As the latest studies make abundantly clear, the transformation of the World Trade Center site was hampered to a shameful degree by the intransigent self-interest of both individuals and institutions. As a result, an effort ostensibly meant to display our country’s unified spirit in response to an unprecedented calamity instead revealed that communal altruism of the sort that helped America to survive the Great Depression and triumph in World War II had largely become a thing of the past. Although all major construction schemes face tremendous problems, the World Trade Center rebuilding encapsulates everything that is wrong with urban development in a period when, as in so many other aspects of our public life, the good of the many is sacrificed to the gain of the few.

The actual and emotional centerpiece of the new grouping is the magnificent National September 11 Memorial, the hypnotic pair of reflecting pools recording the names of victims by the architect Michael Arad, and the surrounding park by the landscape architect Peter Walker, which was dedicated on the tenth anniversary of the disaster.* In May 2014 came the adjacent National September 11 Museum, a much less successful design that resulted from a shotgun marriage between two wholly mismatched firms, the high-style Snøhetta (which designed the trendily off-kilter exterior) and the workaday Davis Brody Bond (responsible for the awkward interiors). This doomed division of labor produced a disjointed building that unintentionally reflects the continuing conflicts over the way the 2001 attacks should be interpreted and responded to.

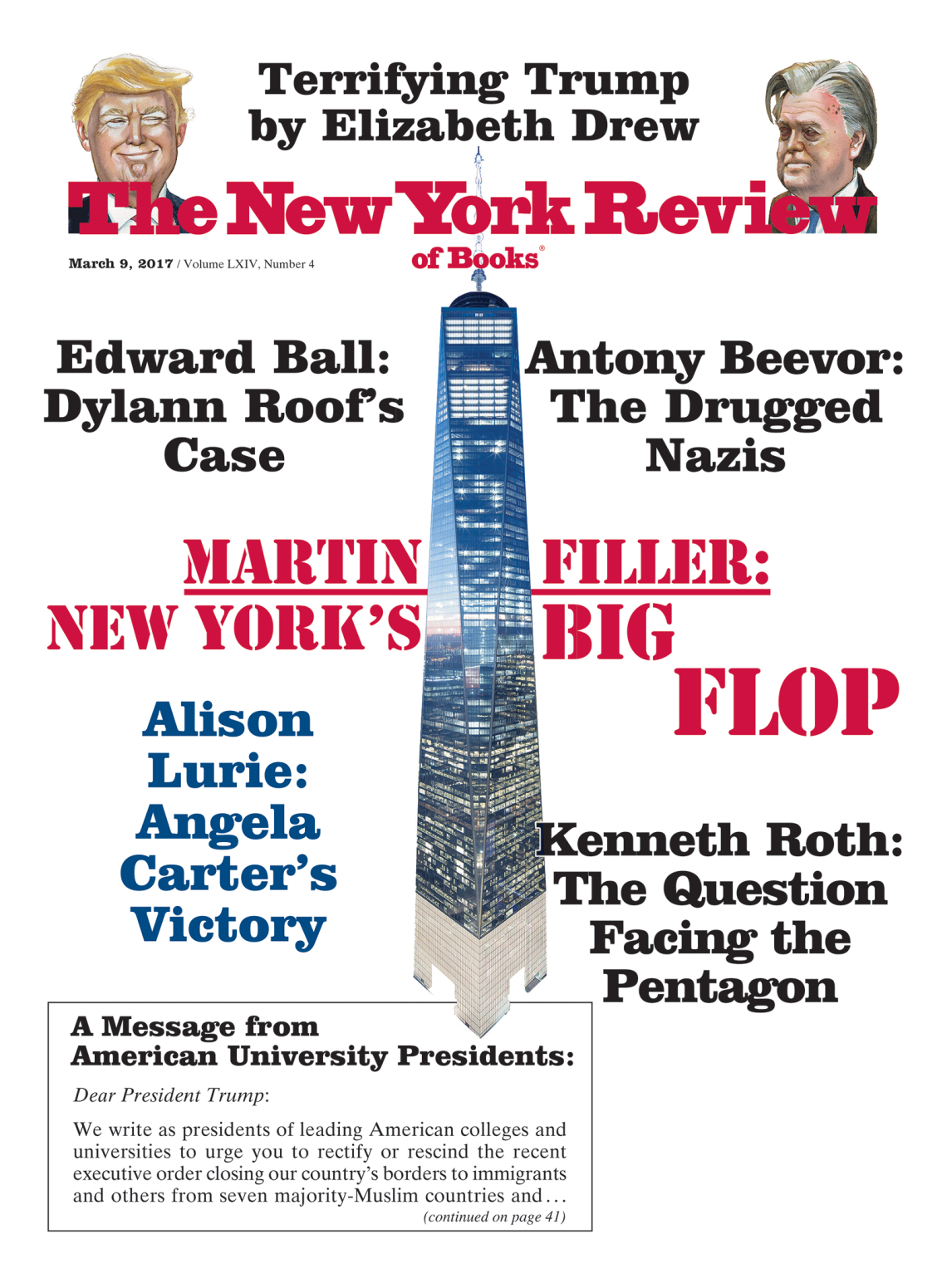

Three of the five reflective, glass-skinned office towers that will ultimately surround Arad’s pools have thus far been finished: the vapid 7 World Trade Center (2006) by David Childs of SOM; the equally disappointing 4 World Trade Center (2013) by Fumihiko Maki; and the Western Hemisphere’s tallest skyscraper, Childs’s One World Trade Center (2013), a 1,776-foot-tall monolith that supplants Minoru Yamasaki’s Twin Towers of 1966–1977. Not as bad architecturally as it is conceptually, One World Trade Center is faute de mieux the best of the lot.

The chief virtues of this building—which was dubbed the Freedom Tower by New York Governor George Pataki but later “rebranded” to tone down jingoistic associations that might scare off potential tenants—are that it effectively addresses the huge open space to its south, including Arad and Walker’s memorial, and overpowers its lackluster neighbors. Though hardly an intriguing work of architecture, it nonetheless succeeds in anchoring the unruly scrum of contiguous lower structures through the sheer force of its gigantic scale and simple sculptural presence.

The building’s symmetrical, upwardly tapering prismatic contours make it stand out clearly against the Lower Manhattan skyline, especially when slanting sunlight gives its four angled corners a clear contrast against the rest of its mirror-like glass cladding. If not ideally proportioned in its height-to-mass ratio, Childs’s tower comes close enough to being an agreeable composition, and is a notable improvement over the architect’s other conspicuous Manhattan skyscrapers—the bloated Postmodern campanile of his Worldwide Plaza of 1986–1989 in Midtown West (which occupies the entire city block between 49th and 50th Streets and Eighth and Ninth Avenues) and his glitzy twin-towered Time Warner Center of 2000–2003 on Columbus Circle.

Advertisement

Unparalleled security concerns required that the reinforced concrete-and-steel base of One World Trade Center, approximately nineteen stories high, be as impenetrable as a 1950s atomic bomb shelter. In a dubious attempt to prettify this fortification, Childs originally intended to cover it with two thousand clear prismatic glass panels and welded aluminum-and-glass screens. However, after $10 million had been spent on this decorative flourish, it proved technically daunting to execute and more conventional glazing was substituted. In the end, One World Trade Center cost $3.9 billion, more than twice the price of Western Europe’s tallest building, Renzo Piano’s $1.9 billion Shard of 2000–2013, on London’s South Bank; this is the world’s most expensive skyscraper by a wide margin.

The tower’s interior is far stranger than its straightforward exterior, understandably because of urgent protective measures. Visitors to the observatory on the 102nd floor (2.3 million came during its first year) are shepherded through a labyrinthine series of unnervingly lighted and plastic-feeling walkways and holding areas on the ground floor, where security checks are made before they arrive at the Sky Pod Elevators. These lifts propel them to the summit in forty-two seconds, while an animated time-lapse video, brilliantly designed by the California firms Blur Studio and Hettema Group, plays on nine seventy-nine-inch high-definition screens that line the cabs.

This simulation imagines how an eastward outlook from the site appeared during the past five centuries, beginning with lightly forested marshes circa 1500 and, a century later, gabled Dutch houses that pop up and vanish. In due course the skyscrapers that made Manhattan world-famous shoot heavenward and are replaced by ever taller ones. Finally, for a fleeting four seconds, we catch a peripheral glimpse of one of the vertically striped Twin Towers, which swiftly vanishes, happily without any sign of what took place. One exits from this intense ride thankful for the majestic panoramic views that extend peacefully in every direction beyond the glass-walled rooftop gallery.

Without knowledge of Ground Zero’s terrible history, Childs’s design would seem even less exceptional, just another super-colossal, shiny skyscraper made possible by all sorts of advanced engineering marvels but unmistakably a thing of the past because of its fundamental lack of forward-thinking urban planning ideas. It seems impossible to see this as anything other than a place-holder for half of what once stood in its approximate place, a feeling reinforced by the eloquent voids of Arad’s heart-rending memorial right in front of it.

The most architecturally ambitious portion of the ensemble, Santiago Calatrava’s World Trade Center Transportation Hub (commonly called the Oculus), opened to the public in March 2016, though with no fanfare whatever, doubtless to avoid drawing further attention to this stupendous waste of public funds. The job took twelve years to finish instead of the five originally promised, and part of its exorbitant $4 billion price will be paid by commuters in the form of higher transit fares. The fortune spent on this kitschy jeu d’esprit—nearly twice its already unconscionable initial estimate of $2.2 billion—is even more outrageous for a facility that serves only 40,000 commuters on an average weekday, as opposed to the 750,000 who pass through Grand Central Terminal daily. Astoundingly, the Transportation Hub wound up costing more than One World Trade Center itself.

Calatrava’s budgetary excesses were already well known among professionals by the time he received this commission in 2003. But the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC)—the joint city-state body established to carry out the reconstruction effort—had just gone through a bruising public struggle to select a master planner for the site, and in its eagerness for an architectural showpiece, it paid insufficient attention to the Spanish architect’s troublesome track record and fell for the maudlin sentimentalism of his design.

What was originally likened by its creator to a fluttering paloma de la paz (dove of peace) because of its white, winglike, upwardly flaring rooflines seems more like a steroidal stegosaurus that wandered onto the set of a sci-fi flick and died there. Instead of an ennobling civic concourse on the order of Grand Central or Charles Follen McKim’s endlessly lamented Pennsylvania Station, what we now have on top of the new transit facilities is an eerily dead-feeling, retro-futuristic, Space Age Gothic shopping mall with acres of highly polished, very slippery white marble flooring like some urban tundra. Formally known as Westfield World Trade Center, it is filled with the same predictable mix of chain retailers one can find in countless airports worldwide: Banana Republic, Hugo Boss, Breitling, Dior, and on through the global label alphabet. (The Westfield Corporation is an Australian-based British-American shopping center company.) Far from this being the “exhilarating nave of a genuine people’s cathedral,” as Paul Goldberger claimed in Vanity Fair, Calatrava’s superfluous shopping shrine is merely what the Germans call a Konsumtempel (temple of consumption), and a generic one at that.

Advertisement

Still to come are 2 World Trade Center by the Bjarke Ingals Group (BIG) and 3 World Trade Center by the office of Richard Rogers. Plans are doubtful for a putative 5 World Trade Center (to replace the former Deutsche Bank Building, which was irreparably damaged by debris from the collapse of the Twin Towers and laboriously dismantled) and no architect has been selected. There will be no 6 World Trade Center to replace that eponymous eight-story component of Yamasaki’s original five-building World Trade Center ensemble, also destroyed on September 11.

2.

The enormous public interest in the resurrection of Ground Zero quickly prompted three books about the first phases of the effort, all aimed at a general readership and published within four months of each other around the disaster’s third anniversary. Goldberger’s Up From Zero: Politics, Architecture, and the Rebuilding of New York (2004) was one of his typically well-reported but never indiscreet overviews. Philip Nobel’s Sixteen Acres: Architecture and the Outrageous Struggle for the Future of Ground Zero (2005) offered a juicier, more anecdotal account of the same events. Both books suffered from a lack of adequate illustrations, a shortcoming rectified by Suzanne Stephens’s pictorially rich compendium Imagining Ground Zero: Official and Unofficial Proposals for the World Trade Center Site (2004). However, even though the recently issued One World Trade Center: Biography of the Building by Judith Dupré is as glamorously visual as one could imagine, her breathlessly boosterish tone makes it seem more like a promotional event than a serious monograph.

Now, more than a decade after the initial flurry of books, we have what is likely to remain the definitive account of this tortuous and unedifying saga, Lynne B. Sagalyn’s Power at Ground Zero: Politics, Money, and the Remaking of Lower Manhattan. Sagalyn, who retired as a professor of real estate at the Columbia University Business School, insists that there are no heroes or villains in her narrative. However, her meticulous and exceptionally clear exposition of the essential facts provides more than enough evidence for readers to come to their own, and often damning, conclusions, especially about the real estate developer Larry Silverstein, who bought a ninety-nine-year lease on the World Trade Center from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey just six weeks before the disaster.

Sagalyn’s exhaustive research has revealed some fascinating interrelationships in the upper echelons of the city’s power elite, which will be unsurprising to those who know how the financial and cultural capital of the US really works, and insider glimpses are rarely revealed as directly as she does here. For example, she tells how the well-connected attorney Edward Hayes, a “New York political infighter” and “go-to guy,” urged Pataki, a former Columbia Law School contemporary of his, to pick Daniel Libeskind’s scheme in the competition for the site’s master plan.

Hayes had been introduced to Libeskind and his business-manager wife, Nina, by Victoria Newhouse—an architectural historian and the wife of the publishing magnate Si Newhouse—who was avid to see Libeskind win the commission. Pataki reassured Hayes that he was already in favor of Libeskind’s proposal and indeed intervened at the last moment to ensure that he was chosen. It was a Pyrrhic victory for the architect, however. Libeskind assumed that winning the contest would also entitle him to design the Freedom Tower, but because of his limited experience with such large-scale projects he was forced to collaborate with Childs, who edged him out of the commission with Machiavellian dispatch.

Si Newhouse resurfaces later in the story when the question of who would actually occupy the Freedom Tower becomes an urgent matter. Newhouse’s Condé Nast Publications was identified as the ideal “anchor tenant” by Silverstein’s longtime leasing broker, Mary Ann Tighe of CBRE, the world’s largest commercial real estate services firm, who had known the publisher for decades. Given the perceived danger of another terrorist attack, this would not be an easy sell, but Tighe recalled that Condé Nast had been previously receptive to an undesirable address at the right price when it relocated from its longtime Madison Avenue headquarters to the newly built 4 Times Square in 1999, when that area still had a seedy aura. (The developer of 4 Times Square, the Durst Organization, received tax incentives estimated at more than $280 million, which allowed it to give Condé Nast very favorable terms, a classic example of corporate welfare at taxpayer expense.) Durst partnered with the cash-strapped Silverstein on One World Trade Center once it became an active, risk-free proposition, and Condé Nast agreed to move to Ground Zero when it was offered yet another sweetheart deal on a property widely deemed to be very difficult to rent.

A more visible display of influence was orchestrated by Herbert Muschamp, the New York Times architecture critic from 1992 to 2004. As his friend Frank Gehry told the writer Clay Risen, they dined together in Manhattan the night before the Twin Towers attack, and the catastrophe so traumatized the critic that he felt unable to leave his forty-fourth-floor Tribeca apartment, several blocks north of Ground Zero, for some time afterward. Thus Muschamp deprived the Newspaper of Record of his immediate insights on the biggest architectural news story of modern times for nearly three weeks. Perhaps to compensate for this glaring lapse, he organized a special issue of The New York Times Magazine that presented his notions of how the site ought to be reconfigured, which was published the Sunday before the first anniversary of September 11.

Muschamp had been dismayed that several months earlier the LMDC and the Port Authority (which owns the Trade Center site but leased the now-vanished Trade Center buildings to Silverstein) selected the architectural and planning office Beyer Blinder Belle (BBB) to develop a master plan. Although that partnership had won universal praise for its exemplary restoration of Grand Central, Muschamp deemed BBB insufficiently adventurous for this assignment. Accordingly he invited many of his favorite practitioners—older figures of the New York avant-garde as well as younger trendsetters—to submit their own ideas and assigned parts of the project to them.

The fact that these hypothetical schemes lacked even the most basic information that architects need to draw up design proposals—a budget and a functional program beyond vague designations (school, arts center, and the like)—seemed not to bother either Muschamp or his nominees. As Sagalyn writes in one of her rare overt expressions of disapproval:

This was not city building. Architecture may be art and city building calls for art-like understanding of the fabric of a place, but a city is not a blank canvas to paint at will as Muschamp was advocating with his study project, most unrealistically….

Irresponsibly, Muschamp had preemptively pronounced his personal opinion of what was likely to result before BBB had even drawn a single line. Did this belong in the news section [sic] of the paper? Where does the press cross the line between presenting the news to inform the public and aiming to become a player by advocating a particular vision—other than on the editorial page?

Yet this self-appointed planner was scarcely oblivious to urban design realpolitik. (Nor were the LMDC and the Port Authority, which withdrew the commission from BBB and announced a competition to find a new planning firm.) Immediately after Libeskind’s master plan was chosen over Rafael Viñoly’s proposal—which was centered by a scaffold-like, smaller reiteration of the Twin Towers that the Times critic championed, but that Pataki tactlessly likened to a pair of skeletons—Muschamp made an astonishing volte-face and wrote that the best scheme had won after all.

3.

This aesthetic influence-peddling, whether in the back corridors of government, the salons of the powerful, or the nation’s most prestigious newspaper, was nothing compared to the nonstop machinations of the pivotal figure in this drama, Larry Silverstein, who before September 11 had been considered a fairly minor player and something of a bottom-fisher among the big deal machers of the New York real estate establishment. Although Sagalyn’s portrait of Silverstein accords with the general outlines of previously published reports, here he emerges even more unfavorably as his actions are recounted in greater detail than ever before, thanks to the author’s extensive interviews and her informants’ willingness to speak candidly about him (an indication of how much rancor he aroused).

At the heart of the matter was Silverstein’s unshakable determination that all ten million square feet of office space lost in the Twin Towers’ collapse be replaced, a position driven by his desire to protect the maximum future profitability of his investment. However, this did not accord with the changing economic realities of postmillennial Lower Manhattan, and his sheer stubbornness struck New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the technocratic urbanists around him as fundamentally uninformed and misguided (to put it in the most polite terms).

Sagalyn quotes Daniel Doctoroff, Bloomberg’s deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding, as pointing out that “Lower Manhattan before 9/11 had a growing residential population, but it had been losing worker population since 1970,” even as the construction of the original World Trade Center was still underway. The changing demographic needs of this part of the city, said Doctoroff, “were swept under the rug in the wake of 9/11 by this kind of nostalgia for the World Trade Center and the tremendous emotion that existed.” The Bloomberg administration favored a varied mix of components with far less emphasis on offices and more housing units, in line with the growing residential character of the Financial District, where many old commercial buildings no longer suitable for today’s high-tech businesses have been converted to apartments, often very costly ones.

But Silverstein’s representatives (including Mary Ann Tighe) aggressively pressed his case for a full ten-million-square-foot build-out, and hammered home the questionable assertion that the boom-or-bust nature of New York City building cycles demanded readiness for the next inevitable upswing (this was before the international market crash of 2008). Conveniently omitted by the developer’s team was the financial history of the World Trade Center. The complex was built during a recessionary period, and it took until the 1980s for it to finally turn a profit; it did so only because of the artificial life support of state government agencies that had been transplanted to the Twin Towers by New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, brother of that quixotic scheme’s mastermind, David Rockefeller.

Bloomberg and his advisers repeatedly tried to gain control of the project and impose the focused leadership and purposeful direction it lacked. Their most ingenious attempt was a Solomonic solution advanced by Roy Bahat, a twenty-four-year-old aide to Doctoroff, who suggested a swap of the land underneath Kennedy and LaGuardia airports—the city owns that real estate but the Port Authority runs the facilities on it—in return for the Trade Center acreage, which is owned by the Port Authority. This would have allowed the city to invoke eminent domain, cancel Silverstein’s lease, and be done with him. Although the Times praised it as “the most creative idea to arise from the Lower Manhattan redevelopment process so far,” the trade-off foundered not only because of the tangled economics of how evaluations for the respective assets would be calculated, but also because it was stymied by officials who foresaw themselves losing power if the deal went through.

As is typical of such betrayals of the public trust, there was more than enough blame to go around. Sagalyn names names, and they include Port Authority Vice Chairman Charles Gargano, described by the author as “‘a loyal Pataki soldier’…said to be riled by the swap proposal, a threat to his influence; he had already been ‘a loser in a bid to control the [LMDC]’. In the end, it was a political decision—for Governor Pataki.” At that time Pataki harbored presidential ambitions and felt that his continuing involvement in rebuilding Ground Zero would elevate his national reputation. As a result of these and other complications, the swap died in June 2003.

Whatever one might think of Bloomberg’s often high-handed approach to urbanism, which tended to favor corporate interests at the expense of other concerns, there can be little doubt that he did a number of very good things for New York City, and would have been a far better overseer of the World Trade Center redevelopment than any other major figure on the scene at that time. Among the institutions involved in the rebuilding, none is portrayed more critically by Sagalyn than the Port Authority, and rightly so. Its preference for investing in chancy real estate speculations instead of focusing on an overburdened transportation system and crumbling regional infrastructure has been a long-running scandal. A thorough overhaul of that bistate agency would seem to be the only solution to correcting the abuses detailed so appallingly by Sagalyn in her quiet way.

High among other factors that greatly complicated the rebuilding of the Trade Center site are recent advances in DNA verification methods. The conjunction of those new capacities with the 2001 catastrophe is the basis for a thoughtful and solidly informed meditation, Who Owns the Dead?: The Science and Politics of Death at Ground Zero by Jay D. Aronson, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and director of its Center for Human Rights Science. Because it is now easier than ever to identify human remains found at sites of mass disasters, expectations ran high among many families bereaved by the Twin Towers attack that they might reclaim some corporeal vestige of their dead relatives. It was once expected that those lost at sea would lie forever asleep in the deep, much as soldiers killed in foreign wars would be buried near where they fell. However, modern science has encouraged a broad belief that the retrieval of physical matter, no matter how tiny, is essential to attaining “closure”—that obsessive yet elusive goal of contemporary grieving.

As of last autumn, remains of 1,113 of the disaster’s victims—or some 40 percent of the death toll—continue to be unidentified. At several points during the slow, painstaking, dignified, and respectful recovery process, officials announced that the search had concluded, but family members who had not yet been given definitive physical proof demanded further forensic investigation.

As it turned out, spot checks confirmed that minute amounts of residue from the victims were still discernible in the surrounding area, a finding that prompted an even more microscopic search that in some areas went inch by inch through newly discovered concentrations of possible physical evidence. This late phase was pursued with a vigilance that the participating experts vouchsafed was much more thorough than any they had witnessed before, verging on the exactitude of an archaeological dig. And indeed, additional names were associated with the powdery particulate. But to what end was this increasingly obsessive search? As Aronson writes:

The thought of unidentified remains is unnerving, especially for a society that wants to believe it has the technical capacity to provide some measure of certainty in an uncertain world…. It is ironic, then, that the individualization of the victims of the World Trade Center has made it more politically palatable for the US government to engage in a seemingly perpetual war that has created innumerable casualties in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, and elsewhere.

This Issue

March 9, 2017

Terrifying Trump

Is Consciousness an Illusion?

-

*

See my “A Masterpiece at Ground Zero,” The New York Review, October 27, 2011. ↩