A seventh-grader I know slipped a copy of Substitute from my bag and buried her nose in it through an entire restaurant dinner with her parents. When I retrieved the book, I asked what she thought. “The writer does a good job of communicating how despicable he thinks these children are,” she said darkly.

This is patently 180 degrees wrong. But kids say the darnedest things, as Nicholson Baker reminds us many times in Substitute, his tightly focused account of twenty-eight days of substitute teaching in Maine public schools in the spring semester of 2014:

“Smells like marshmallows in here.”

“If you say Yankees in this class, it’s a swear.”

“We have to go with him [to the restroom] because he makes bad choices in there.”

I don’t know how Baker managed to record so much speech—the book is more than seven hundred pages, most of it dialogue—while trying to control his classes and get some teaching done. A Moleskine notebook is mentioned, and yet Substitute reads like a lightly curated, benign surveillance tape, somehow capturing all the downtime, chaos, non sequiturs, and lost-in-the-infosphere weirdness of a modern American schoolroom.

Baker has a prodigious talent for illuminating minutiae, established brilliantly in his first novel, The Mezzanine (1986), which takes place entirely within the antic mind of an office worker named Howie during a single escalator ride in an office building lobby, and since deployed, often to hilarious effect, in book after book, both fiction and nonfiction. He likes to set extreme narrative challenges for himself: Vox (1992) is a novel about a single phone call, the ultimate he-said she-said, with scarcely a line of narration; Human Smoke (2008) is a pacifist reading of World War II built almost entirely on primary sources. For Substitute, Baker confines himself to the school day, making each one-day assignment a chapter, while renouncing virtually all of his enormous descriptive gifts.

The subject matter may have forced this renunciation. Baker feels obliged, understandably, to change the names of students, teachers, and schools, and to omit identifying physical traits. So we are left with an extremely large cast of featureless characters and aggressively bland settings. A chapter begins, “Buckland Elementary was another one-story eighties brick school in the middle of a nowhere of pine trees.” That’s it. A secretary hands him a clipboard. The presence in his class lists of French and Scots surnames that evoke the region’s history is noted, with no examples or elaboration. There are brief flashes of the old verbal flair, as when a hole puncher leaves “a flutterment of paper dots on the carpet” or a class becomes loud and “the noise was like orange marmalade.” When Baker allows himself a dip into his own memories of learning to read—he recalls “weeping over the unphonetic wrongness of the word dark (dah-erk?)”—the precision and tender detail are reminiscent of Nabokov, one of his early heroes.

But these moments are the exception, and they reminded me of a self-mocking passage on careerism and literary style from his 1991 ode to John Updike, U and I: A True Story:

If you begin as something of a mannerist and phrasemaker, you offer yourself the hope of gradually disgusting yourself into purity and candor; if on the other hand you start by affecting a direct Saxon scrubbedness, then when a decade or so later you are finally ready to cut through the received ideas to say something true, the simplicity will feel used up and hateful and you’ll throw yourself with a wail on the OED and bring up great dripping sesquipedalian handfuls while your former admirers shake their chignons in pity.

Has Baker entered his Saxon scrubbedness period? I don’t think so. His story here is morally complex and exhausting, and the subjectivity of the teacher-narrator colors every line. And yet the reality of the kids demands a maximum of attentive transparency, which means a minimum of writerly flourish. What’s required is less eye-as-a-camera than a perfectly pitched ear and a high emotional IQ.

Baker has these in spades, and with them captures the flow of banter, amusement, squabbling, dire boredom, perfectly pitched demotic speech, small lurches of actual learning, and scenes of minor heartbreak that fill a school day. What he doesn’t have is developed characters, and that’s because he’s a substitute who rarely sees the same kids twice. He teaches, what is more, all grades, from kindergarten to high school seniors, which makes for stark discontinuities of mood and pedagogic approach. The reader may feel a frequent need to double-check—wait, are these kids seven or seventeen? For Baker, teaching elementary school is actually more frightening, he confides, than high school. It feels more consequential.

Advertisement

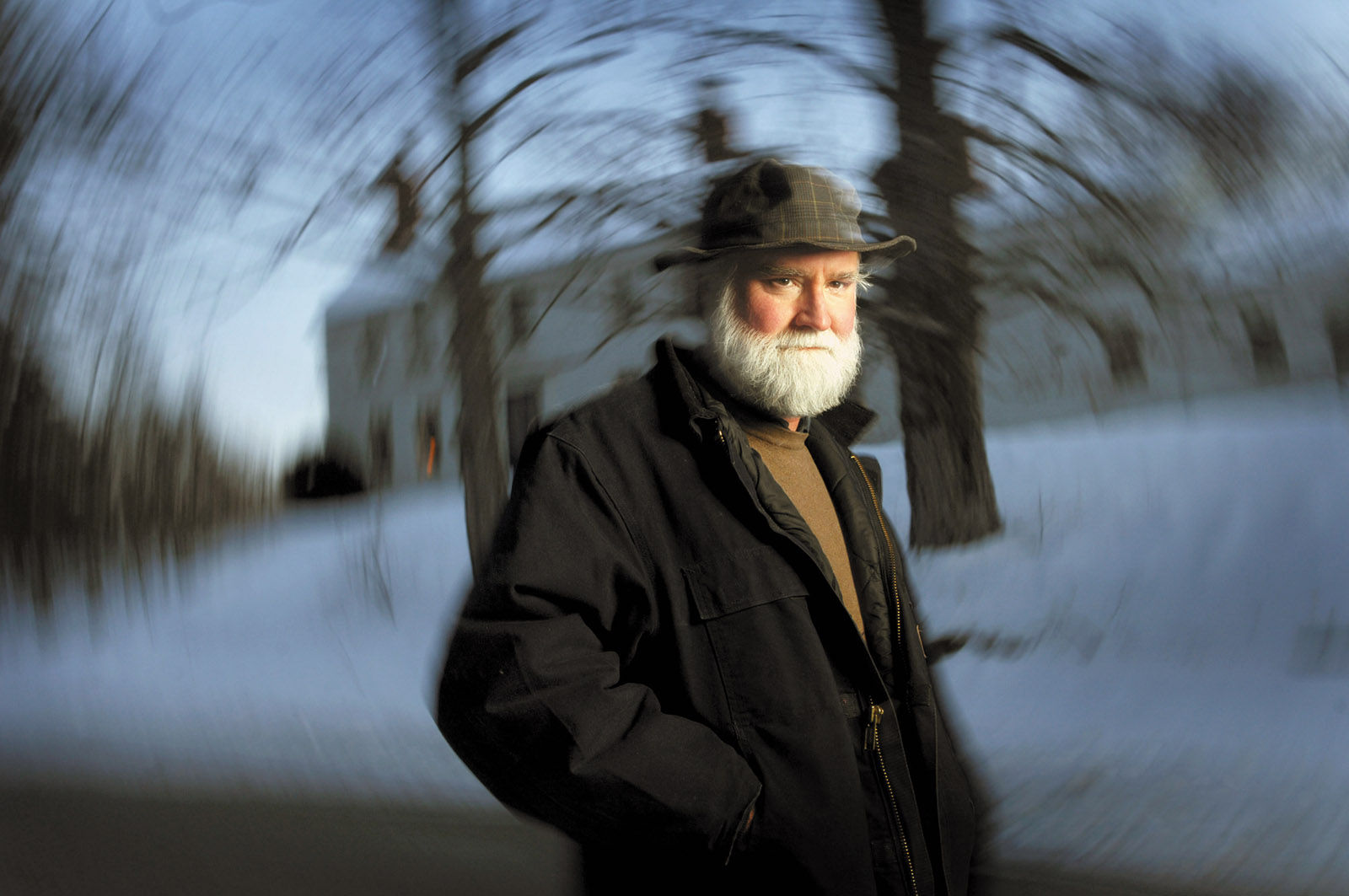

And it is the tall, white-bearded substitute’s emotions, his eagerness and dashed hopes, his anxiety and his elation in the fleeting moments when things go well, that form the connective tissue that makes Substitute more than a heroic reporting feat. We suffer alongside him through the lessons that don’t work, the longueurs and deflating nonresponses from faceless students with made-up names—Misty and Kiefer and Jayson: “Mhm,” says Melvyn. “My waist hurts,” says Agnes. “It’s boe-ring,” says someone named Joseph. Somehow, a sly comic timing lurks in even the bluntest ripostes:

“Great idea!” I said. “Did you come up with that?”

“No.”

Baker the character is vulnerable, curious, expansive, self-critical. He gets a mortifying nosebleed. He has a habit of addressing himself in the restroom mirror—“You hopeless jackass.” Or in the decompression chamber of his car—“I’m hurtin’ real bad,” he says aloud, and we’re hurtin’ with him, even as we grin. Baker can be nakedly candid with students, who reliably flatten him with fine irony. Here he is addressing a group of high school kids eating lunch in his classroom:

“The thing that’s hard—I’m sorry to interrupt you guys, but I’m lonely—the thing that’s hard is that if you’re a regular teacher, you actually have to get the kids to learn something. That’s hard. A substitute can just enjoy it. People say funny things, do amazing projects, and I just take it in.”

“It’s a dream job,” said Jill; Penelope laughed.

At the end of a middle school class that goes wondrously well, achieving a “mystically whispery mood,” the kids depart, and Baker reports, “Nobody said goodbye to me, which hurt my feelings slightly.”

Another class, of fourth-graders, goes well after Baker starts riffing on inventions, one of his favorite topics. Gunpowder, glasses, mirrors, the iPhone, the SmartBoard, the pencil sharpener:

“Someone invented school,” said Jasper.

“Ah,” I said. “Who invented school, and WHY?”

“I’m looking for who invented homework,” said Jared. “I’m mad at him.”

“Whoever did that is bad,” said Tina.

Baker loves knowing precise, surprising things. Yet another successful lesson consists of reading from books of “weird facts.” Kids blink about five million times a year. Panda droppings can be made into paper. Slugs have three thousand teeth and four noses. Even as these little info bombs are flying around the classroom, we hear exchanges of ineluctable accuracy:

I said, “Spiders have clear blood, people. Know that!”

“Then how come when you smush them, it’s like ull?” said Jade.

Baker, for my money, may be the only writer in America who could catch that “it’s like ull.”

“Let’s learn another fact, shall we?”

“No-ho-ho-ho!” said Sunrise, putting her head in her arms and pretending to weep.

Baker does not overestimate his own impact. With a class of alienated “special-needs” high-schoolers, he concludes, “My role was to function as straight man, to give these kids the pleasure of avoiding meaningless schoolwork. And that was maybe a useful role.” He dazzles first-graders with a sleight-of-hand trick called the Chinese egg drop, which his father taught him. It becomes a student favorite. “This magic trick was the most successful piece of teaching I’d ever done. Thank you, Dad!”

Baker often shares classrooms with other teachers, either substituting for an “ed tech”—responsible for children within a class who need individual attention—or teaching a class that includes an ed tech. His fellow teachers receive fuller descriptions than the students, and while some of them come across as wry comrades and effective teachers, the more memorable seem ineffectual, annoying, or both. They’re preoccupied with opaque education jargon (“Activate Prior Knowledge! Identify Text Structure! Monitor Comprehension!”), dubious educational software, obtuse assignments, and reprimanding and punishing kids for small infractions. THEY TEND TO BELLOW in all-caps at their charges, and they drive both Baker and the reader slightly crazy. He recognizes that his own job is relatively effortless—“It was easy for me to be ‘cool’ by making a few mildy subversive references, but they had to keep a lid on the lunacy day after day”—and yet he can’t resist doing some scolding of his own:

I found myself wondering whether Mrs. Thurston would want to be treated the way she treated her students. “Do Unto Others” is a lovely maxim, but the golden rule doesn’t operate fully in school: The children have no choice. They must go. Teachers are paid and choose to work there; children are unpaid and must endure rhombuses and homophones and tally marks and recess punishments whether they want to or not. Teachers have total power over their lives, and some of them are corrupted by it.

Baker has the unremarked advantage of an education broader and deeper than what is offered by the notoriously undemanding system of American teacher education. Still, even the laidback, cool-dude substitute loses it sometimes. An obnoxious ninth-grader sets him off:

Advertisement

“God dang,” I said. “What’s up with you? Just get some homework out and pretend to do it. Put a piece of paper or a freaking iPad in front of you and do something with it. Don’t poke. It’s ridiculous!”

By the end of his tenure, he is even sometimes driven to all-caps. “VOICES AT ZERO!” “MY FRIENDS, IT’S TOO LOUD.”

Baker is largely uninterested in generalizing. He may have more experience in American public schools than, say, Betsy DeVos, our new secretary of education, and yet he is not here to weigh in on the debates about standardized testing, school choice, national standards, market-based reforms, or a national curriculum. We are all aware, at least vaguely, that US schools have fallen dismally in international rankings for math, science, and reading, underperforming many countries in East Asia and Europe, including some that spend far less on education per student.

This awareness begs a question—about why American schools are in decline—that Baker answers obliquely by conveying so carefully the addled particulars of various classrooms that we may take as a fair sample of American schooling. At times, he tries to answer it more directly. “The basic problem was that we live in a jokey, chatty world—which is a good thing—but a room full of eighteen jokey, chatty children is an inefficient place to learn.” This observation occurs in a second-grade class. It seems, if anything, even more germane to middle and high school.

In a ninth-grade classroom, Baker allows himself a riff on class size and efficiency:

One grownup can’t teach twenty digital-era children without spending a third of the time, or more, scolding and enforcing obedience. What if we cut the defense budget in half, brought the school day down from six hours to two hours, hired a lot of new, well-paid teachers who would otherwise be making cappuccinos, and maxed out the class size at five students? What if the classes happened in parental living rooms, or even in retrofitted school buses that moved like ice cream trucks or bookmobiles from street to street, painted navy blue? Two hours a day for every kid, four or five kids in a class. Ah, but we couldn’t do any of that, of course: school isn’t actually about efficient teaching, it’s about free all-day babysitting while parents work. It has to be inefficient in order to fill six and a half hours.

Baker’s policy views, however eccentric, tend to rise directly from the battlefield—from, that is to say, the classroom—and thus have a certain authority. The ubiquitous iPad?

The means [that students] had available to pass time productively had improved dramatically because of the iPad. In the old days, they would have made spitballs, or poked their neighbors—now they could watch mudding videos, which actually interested them, or take pictures of each other, or play chirpy video games. The iPad had improved their lives.

Teaching the parts of speech?

This was all lost time, it seemed to me, and for some kids it spread confusion and jitteriness, which on a normal day would then have led to their being “clipped down” and deprived of recess. Adjective—what an unlovely word for something juicy and squeezable and wild and elusive and fungible and adamantine and icy-blue. There were nouns and verbs and adjectives in play many thousands of years before anyone took the time to sort and name these abstractions. An eon of language precedes linguistics. You can write a three-decker novel or a whole history of Transylvania without knowing or caring in the least what the parts of speech are—and in first grade, unless you’re an unusual little person who takes an Aristotelian pleasure in verbal classification, it’s an unnecessary encumbrance and a distraction.

The same goes for do-it-yourself phonetics. It’s supposed to build self-esteem but it does the opposite. Baker much prefers old-fashioned spelling instruction. Homework? Another huge waste of precious childhood time. “My homework-free generation has done just fine.” Reading novels and stories for English—excuse me, for Language Arts—is spoiled from the outset by brain-deadening “analysis sheets” that accompany each assignment:

The people to blame were educational theorists who thought that it was necessary for all students to do literary criticism. If you want unskilled readers to read, I thought, make them copy out an interesting sentence every day, and make them read aloud an interesting paragraph a day. Twenty minutes, tops. If you want them to take pleasure in longer works, fiction or nonfiction, let them read along with an audiobook. Don’t fiddle with deadly lit-crit words like tone and mood.

His distaste for the lit-crit approach to teaching hits a nadir on a May morning when his students are made to watch a video called Auschwitz: Death Camp. Oprah Winfrey interviews Elie Wiesel at Auschwitz, with historical footage of utmost horror: “pictures of piled, starved, naked Jewish bodies, bodies being bulldozed, bodies tossed into trenches full of more bodies.” The assignment sheet that accompanies this film is terribly complicated, asking for an essay about different ways to tell a Holocaust survivor’s story, with assorted “criteria” and “multipliers.” Baker writes:

The Holocaust assignment conformed to the following standards: Text Structures Level 6, Opinion/Argument Level 7, and Writing Process Level 5. It used the mass murder of Jews to evaluate the efficacy of various media.

He observes that the documentary, fetched from YouTube, is actually well made, but

as I watched the kids sitting slack-faced, in plump-cheeked, polite silence, surreptitiously checking their text messages every so often, glancing up at the screen and away from it to think their own thoughts, adjusting their hair, while laughter and shouts floated in from the hall, I knew that this was the wrong documentary to be showing to a group of choiceless, voiceless high school kids at eight-thirty on a Monday morning, in connection with a compare-and-contrast media-studies essay assignment.

Baker’s sympathies, pace my suspicious young dinner companion, are always with the kids. “Loud bad funny brilliant sullen blithe anxious children. If I were a real teacher, I would go completely nuts. I love them.”

A handful of students emerge as actual characters in Substitute. There’s Jade, a self-described “science nerd” who is determined that the reason fingers get wrinkled after soaking in water is to increase their grip. Baker disagrees, but Jade will not be dissuaded. Class rolls on, and later, “Jade, tapping a page she’d found in another book, whispered to me: ‘Improved grip.’” Jade persists as a class wit and reliable fount of weird facts. Carson, a sixth-grader, is a wired disrupter who, after a painful contest of wills, gets under Baker’s skin so thoroughly that the substitute marches him down to the guidance office. Afterward, Baker, rattled, reflects, “Middle school was destroying him. I was part of the machine of his destruction.”

Sebastian is a math whiz with insomnia, a sweetheart who’s being disturbingly overmedicated. Lucas is a tough guy who’s been in jail. He fascinates a class with tales of solitary confinement and inmate suicide, and later infuriates Baker with his refusal to work or accept help. Then there’s Paloma, the middle-schooler who says, after Baker counsels her not to let “them” break her spirit, “I kind of break my own spirit sometimes.” Paloma is an artist with a mordant turn of phrase. Her father, we learn quietly, died recently.

I once taught secondary school for a year, and these more fleshed-out students reminded me sharply of my long-ago students—the way some kids, as you came to know them, absolutely pierced you with their individuality, their vulnerability. The school where I taught couldn’t have been more different, at a glance, from these computer-glutted Maine schools. It was in a “coloured” township outside Cape Town during the bad old days of apartheid. The school was miserably underfunded. Our students went on strike for three months, protesting apartheid in education, and we improvised an alternative curriculum, abandoning the “brainwashing” of the state-mandated course material. The deep question during those months, asked with steady ferocity by campus activists, was “What is school for?” This, as it happens, is the same question Baker considers, from various angles—in a radically different setting, of course—in Substitute.

But the political setting for American public education is changing rapidly now. President Trump talks about “failing government schools” and has proposed spending $20 billion to help families move away from them. Education will clearly be a critical front in his administration’s planned assault on the American public realm—a comprehensive effort to privatize everything from roads to prisons to air traffic control. Betsy DeVos is an evangelical Christian and billionaire whose father-in-law cofounded Amway. She is a lifelong exponent of private, parochial, and for-profit charter schools, and a major force behind the charter school movement in her home state of Michigan. DeVos is, as Stephen Henderson, of the Detroit Free Press, points out, not an educator at all but, in effect, a lobbyist for the charter school industry.

Michigan’s charter schools, meanwhile, are among the least regulated and worst performing in the nation, and their impact on public schools in poor districts has been ruinous.* At her confirmation hearings, DeVos was clearly unfamiliar with both basic federal education law and long-running debates about accountability in public-funded education. She declined to say whether guns should be allowed in schools, noting that they might be needed in states like Wyoming to deter “potential grizzlies.” Her performance at the hearings reminded me of some of the more hapless, ill-prepared students in Substitute. Then she was confirmed.

-

*

See David Arsen, Thomas A. DeLuca, Yongmei Ni, and Michael Bates, “Which School Districts Get into Financial Trouble and Why: Michigan’s Story,” Education Policy Center at Michigan State University, November 2015. ↩