Rachel Cusk has been a prominent novelist for over twenty years in Great Britain, since her first book, Saving Agnes, won the Whitbread First Novel Award in 1993. She has since published eight more novels, including her new book, Transit. Until recently, however, it is for her three memoirs that she has been chiefly known in the United States.

The first, A Life’s Work (2001), is a witty and unsparing—some might say harsh—examination of the demands of new motherhood. The Last Supper: A Summer in Italy (2009) chronicles her family’s two-month sojourn in Tuscany: Adam Begley, reviewing the book in The New York Times, likened it to “a sour, highbrow pastiche of Peter Mayle’s books about Provence.” Her most recent personal chronicle, Aftermath (2012), was written after the breakup of her marriage. Frank, personal, and fierce in its critique of the underlying dynamics of the institution of marriage, the controversial book earned her passionate supporters and detractors both. She herself said, in an interview with Kate Kellaway in The Guardian, that “without wishing to sound melodramatic, it was creative death after Aftermath. That was the end. I was heading into total silence—an interesting place to find yourself when you are quite developed as an artist.”

Cusk, in this interview, speaks of frustration with the novel form, and of a concomitant sense that her autobiographical forays were finished, even though “I’m certain autobiography is increasingly the only form in all the arts. Description, character—these are dead or dying in reality as well as in art,” she said. As a writer, her response was to forge a new form for her work, a sort of semiautobiographical novel in which the first-person narrator is largely absent or erased, serving chiefly as the recorder of the lives—or more accurately, the stories of the lives—of others.

Transit is Cusk’s second novel in this new vein, following the highly acclaimed Outline (2014). A third novel is expected to complete the trilogy about a writer named Faye’s experiences following the breakdown of her marriage. Outline, set in Athens where she teaches a summer writing course, recounts Faye’s encounters with friends, acquaintances, students, and an unnamed Greek man she meets on the plane from London, who takes her out on his boat and shares with her his complicated family history. Transit, on the other hand, takes place in London, where Faye is renovating the former council flat she has purchased, to make a new home for herself and her two young sons. Here, too, the reader encounters the life stories of former lovers, of her friends and relatives, of her hair stylist and the builders working on her flat—but in Transit, glimmers of Faye herself emerge more clearly than they do in Outline, perhaps in part because in London—as opposed to Athens—she has a place in the city and a history; and perhaps because just as her flat is undergoing renovation, so too is Faye’s spirit: she is in transition to be sure, but hers is no longer a fully “annihilated perspective,” to use Cusk’s own language from the Guardian interview.

In Aftermath, Cusk writes:

Form is both safety and imprisonment, both protector and dissembler: form, in the end, conceals truth, just as the body conceals the cancer that will destroy it. Form is rigid, inviolable, devastatingly correct; that is its vulnerability. Form can be broken. It will tolerate variation but not transgression; it can be broken, but at what cost? If it is destroyed what can be put in its place? The only alternative to form is chaos.

She refers here to the institution of marriage, but her meditation applies also to artistic endeavor: navigating the tension between formal constraint and freedom is at the center of a writer’s undertaking. Familiar forms, shaped by convention, allow a certain flexibility (“it will tolerate variation,” as Cusk observes), but only within limits. Dissatisfaction with the form of the realist novel is not new (consider Flaubert, who wanted to write a book “about nothing,” and who claimed to “detest what is conventionally called ‘realism’”), but it is now widespread, and includes intolerance for artificial structures of character development, the willful machinations of plot, and the presumption of authorial omniscience. Attempts to find new ways of telling, and of telling more “honestly,” have turned, sometimes exhilaratingly, to the “autobiography” to which Cusk refers—notably in the fictions of Karl Ove Knausgaard or Sheila Heti, or in literary memoirs like Maggie Nelson’s, or Cusk’s own.

Outline and Transit, however, turn away from self-involvement and draw formal inspiration from a particularly powerful antecedent: the work of W.G. Sebald, whose revolutionary fictions eschew the familiar pleasures of animated characters in action and a rising narrative arc with a climax and dénouement; they rely, instead, on self-consciously crafted summaries of individual life stories. Sebald’s The Emigrants, published in English in 1996, is comprised of four such narratives, thematically linked in an illumination of the legacy of World War II and its trauma and loss. Sebald’s semiautobiographical narrator is both incidental and essential, largely self-effacing. He emerges—as does Cusk’s Faye—chiefly through what he chooses to relay about others.

Advertisement

Cusk’s primary concern is familial relationships—the constant, impassioned, and often agonized dance between men and women, between parents and children—and she deploys Sebaldian techniques (without adopting his distinctive use of old photographs) to explore these broad concerns. In Outline, Faye’s own life is almost entirely absent—with the exception of phone and text communications from her absent sons (“Where’s my tennis racket?”) and from Lydia, the mortgage broker calling from the UK about Faye’s application to increase her loan (and tellingly the only person in the novel to utter the narrator’s name). Faye, in a rare moment of self-revelation, asserts:

I had come to believe more and more in the virtues of passivity, and of living a life as unmarked by self-will as possible. One could make almost anything happen, if one tried hard enough, but the trying—it seemed to me—was almost always a sign that one was crossing the currents, was forcing events in a direction they did not naturally want to go…. There was a great difference, I said, between the things I wanted and the things that I could apparently have, and until I had finally and forever made my peace with that fact, I had decided to want nothing at all.

In Transit, the reader becomes more acutely and recurringly aware of Faye as a particular individual. Her two sons are no less remote than they were in Outline, in this case sent to their father’s house for the novel’s duration, present once again only on the phone; but in this instance, their absence seems to lend Faye a more, rather than less, distinct sense of self. While she remains largely in the background—in a highly entertaining section about her participation on a panel at a literary festival, she recounts over almost twenty pages the self-indulgent autobiographical bloviating of her two male counterparts, and concisely records her own contribution thus: “I read aloud what I had written”—she nevertheless emerges as a person with a will, opinions, and a capacity to act.

She buys a flat against the advice of her real estate agent and embarks on its renovation. She encounters Gerard, a former boyfriend, and as he tells her about his life in the intervening years and about his family, she declares that “it seemed to me that most marriages worked in the same way that stories are said to do, through the suspension of disbelief,” thereby acknowledging her distinct perspective. She asks Dale, her hair stylist, “whether he could try to get rid of the grey.” And out on a date with a man (“someone I barely knew”), she portrays her vindictive downstairs neighbors in ways that imply that she herself is, indeed, as much a character in a story as are any of the others in her narrative:

On top of that, I said, there was something in the basement, something that took the form of two people, though I would hesitate to give their names to it. It was more of a force, a power of elemental negativity that seemed somehow related to the power to create. Their hatred of me was so pure, I said, that it almost passed back again into love. They were, in a way, like parents, crouched malevolently in the psyche of the house like Beckett’s Nagg and Nell in their dustbins.

This gesture toward the mythical is palpable elsewhere also: whereas in Outline, Faye seemed to be filtering the stories of her friends and acquaintances through the lens of their marriages, with a particular focus on the repeated failure of those relationships, both romantic and familial, in Transit she elicits accounts of coping, of the ways in which, in spite of limitations, her subjects have managed to persevere and even upon occasion transcend their failings. Dale the stylist explains a recent period of crisis “in which every time he saw someone he knew or spoke to them…he was literally plagued by this sense of them as children in adults’ bodies.” He dates this state from a New Year’s Eve gathering where he felt “there had been something enormous in the room that everyone else was pretending wasn’t there.” Faye asks what it was: “‘Fear,’ he said. ‘And I thought, I’m not running away from it. I’m going to stay right here until it’s gone.’”

Advertisement

While Dale’s story is one of apparent triumph—he has come to feel at ease in his skin, alone—others are less unequivocal. But any grain of self-awareness has about it a feeling of triumph, as when Faye’s tutorial student Jane describes her flirtation with an older, married photographer, and, pressed by Faye, explains that its allure lay in “the feeling of being admired…by someone more important than me. I don’t know why, she said. It excited me. It always excites me. Even though, she said, you could say I don’t get anything out of it.”

Faye unstintingly brings others’ personal stories to the reader: she offers us Gerard, her long-ago lover, who still lives in the flat they once shared, now with his professionally driven Canadian wife Diane and their daughter, Clara, the focus of his life. We encounter Faye’s old friend Amanda and her troubled builder-boyfriend Gavin, who keeps promising to move in but keeps living instead with his sister in Romford because “it’s easier to run his business from there, but I know it’s because he can watch telly and eat a takeaway and no one expects him to talk.” There is, too, Pavel the Polish builder, whose wife and family are back in Poland in the dream house in the forest that he built for them, a house that is the cause of a painful rift with his father. Finally, there is Faye’s cousin Lawrence, his second wife Eloise, and the guests at their fogged-in rural dinner party—each of them prepared, in spite of the brouhaha and distractions of children and their bickering, to divulge their personal stories. As a woman named Birgid puts it to Faye, “‘I like it that you ask these questions,’ she said. ‘But I don’t understand why you want to know.’”

There may be, we surmise, numerous reasons: in order that Faye may feel less isolated, or may better understand her own situation, or in the hope that she may find courage or wisdom heretofore unimagined, or indeed as part of a broader morality play for Faye’s edification and the reader’s. Or again, perhaps Faye teases out these stories in order simply to hide behind them, using this literary form, too, as “both protector and dissembler,” obscuring herself in the superior safety of the listener (which is, of course, always the position of a book’s reader).

It is hence most powerful—and pleasing, for the reader as for Faye—when the man with whom Faye is on a date finally takes her arm, and she steps out at last from behind the emotional arras:

A flooding feeling of relief passed violently through me, as if I was the passenger in a car that had finally swerved away from a sharp drop.

Faye, he said.

Later that night, when I got home and let myself into the dark, dust-smelling house, I found that Tony had put down the insulating panels….

Just as, in Outline, Lydia the mortgage broker was the first and only person to call Faye by her name, almost at the novel’s end (and in a question: “Is that Faye?”), so too, late in Transit, this suitor is the first and only person to name our protagonist. That he does so not as a question nor in a larger sentence, and not even in quotation marks, feels significant: here, at last, Faye is seen for herself. Which of course in turn implies that she has a self to see—that she is no longer “annihilated.”

Cusk allows her silences to speak too, and the line break between the speaking of Faye’s name and “Later that night” is filled with import: we gather by the novel’s end, albeit obliquely, that this man, this source of relief, is unlikely to disappear. (Of course, the contradictory implications of this development are worth analyzing: that Faye herself, and the reader too, should experience pleasure and relief at the prospect of the protagonist’s romantic attachment, however sparingly described, is strictly speaking at odds with Cusk’s broader enterprise, which presents itself as a rebellion against conventional narrative satisfactions.)

Faye tells her date not only about the dreadful downstairs neighbors, sickly John and his vindictive spouse Paula, most vividly described:

She was a powerfully built, obese woman with coarse grey hair cut in a bob around her face. Her large, slack body had an unmistakable core of violence, which I glimpsed when she suddenly turned to take a vicious swipe at the shrivelled dog—who had been yapping ceaselessly throughout my visit—and sent him flying to the other side of the room.

She also tells him about her shifting understanding of her own agency:

For a long time, I said, I believed that it was only through absolute passivity that you could learn to see what was really there. But my decision to create a disturbance by renovating my house had awoken a different reality, as though I had disturbed a beast sleeping in its lair. I had started to become, in effect, angry. I had started to desire power, because what I now realised was that other people had had it all along, that what I called fate was merely the reverberation of their will, a tale scripted not by some universal storyteller but by people who would elude justice for as long as their actions were met with resignation rather than outrage.

Faye’s ruminations pertain to her own life, but like much in these novels, they echo outward, articulating wisdom about human experience more universally. Faye’s adopted passivity in Outline is not more or less true than her apprehension of willfulness (her own and others’) in Transit: and both affect not only her own choices but those of all whose stories she records. In this way, Cusk pulls off a rare feat: richly philosophical fiction—addressing nothing less ambitious than how to live in relationships with others—in which ideas are so successfully and naturally embedded in the quotidian that the reader can choose whether or not to acknowledge them.

Outline and Transit are being hailed as masterpieces, not without cause; if anything, the new book is even stronger than its predecessor. Cusk has long been one of the finest and most invigorating stylists writing in English, graced with scientific precision, meticulous syntax, and a viperous wit. I take enormous pleasure in her sentences. In the opening pages of Outline, she writes about Faye’s seatmates on an airplane:

On one side of me sat a swarthy boy with lolling knees, whose fat thumbs sped around the screen of a gaming console. On the other was a small man in a pale linen suit, richly tanned, with a silver plume of hair. Outside, the turgid summer afternoon lay stalled over the runway….

This thumbnail sketch displays a delight in its diction that is both evocative and musical—those “lolling knees,” that “silver plume”—and a certain humorous frank cruelty—those “fat thumbs” speeding—that recalls Muriel Spark.

But while Cusk’s fiction has, from the first, been replete with stylistic felicities; and while she has previously challenged fictional form in intriguing ways (her novel The Lucky Ones (2003), a necklace of linked narratives, is formally reminiscent of Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad (2010), which it predates by seven years), the novels failed, somehow, to reach a broad readership in North America. Her memoirs fascinate and provoke, but can seem too tightly filtered through her intense, often ungenerous, perspective. She has found, in these latest books, a mode of narration that affords vital leeway for her formidable intellect, innate wit, and keenly observant eye, while reining in any excesses of malice or hints of self-indulgence.

With the second volume now to hand, it proves inaccurate to suggest that Outline and Transit have no traditional narrative arc. While it remains subtle, couched in scintillating, substantive digressions—summaries of decades in adult lives, potted histories of famous artists, explanations of dog breeding, painfully accurate renditions of family squabbles—Faye’s own evolution emerges: a woman undone by the end of her marriage, painstakingly reconstructing a new, ever-contradictory, self. In Outline, Faye reflects, watching a family enjoy a day’s outing on a boat:

When I looked at [them], I saw a vision of what I no longer had: I saw something, in other words, that wasn’t there. Those people were living in their moment, and though I could see it I could no more return to that moment than I could walk across the water that separated us. And of those two ways of living—living in the moment and living outside it—which was the more real?

Whereas, by Transit’s conclusion, there is the prospect of a new beginning:

Through the windows a strange subterranean light was rising, barely distinguishable from darkness. I felt change far beneath me, moving deep beneath the surface of things, like the plates of the earth blindly moving in their black traces.

It might be naive to call this “hope”; but at the least, Faye’s cousin Lawrence deems it “truth”: “Fate, he said, is only truth in its natural state. When you leave things to fate it can take a long time, he said, but its processes are accurate and inexorable.” However long it takes, Cusk’s readers will be ready to wait.

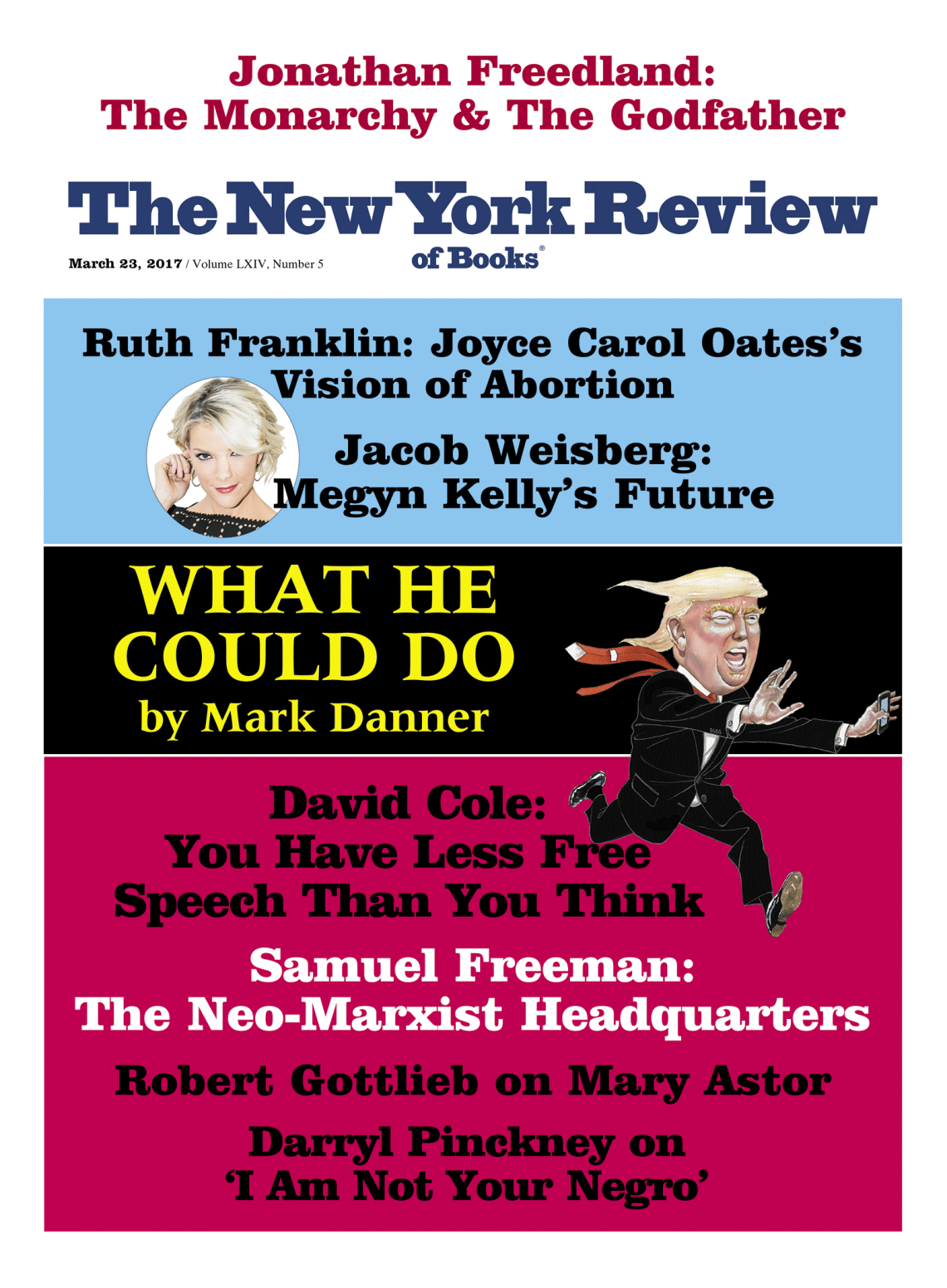

This Issue

March 23, 2017

What Trump Could Do

Under the Spell of James Baldwin