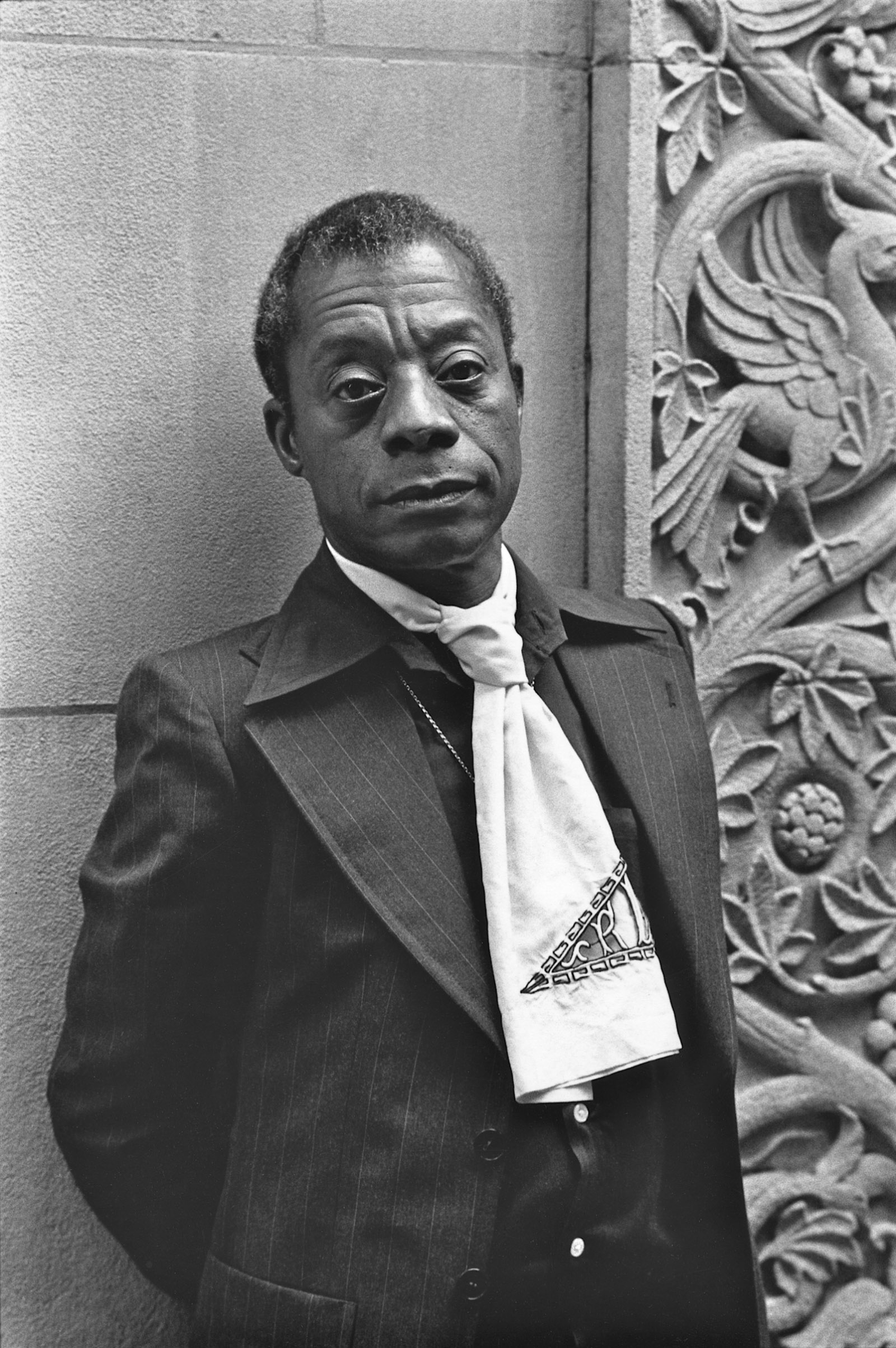

When James Baldwin died in 1987, at the age of sixty-three, he was seen as a spent force, a witness for the civil rights movement who had outlived his moment. Baldwin didn’t know when to shut up about the sins of the West and he went on about them in prose that seemed to lack the grace of voice that had made him famous. But that was the view of him mostly on the white side of town. Ever-militant Amiri Baraka, once scornful of Baldwin as a darling of white liberals, praised “Jimmy” in his eulogy as the creator of a contemporary American speech that we needed in order to talk to one another. Black people have always forgiven and taken back into the tribe the black stars who got kicked out of The Man’s heaven.

Baldwin left behind more than enough keepers of his flame. Even so, his revival has been astonishing. He is the subject of conferences, studies, and an academic journal, the James Baldwin Review. He is quoted everywhere; some of his words are embossed on a great wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Of all the participants and witnesses from the civil rights era, Baldwin is just about the only one we still read on these matters. Not many pick up Martin Luther King Jr.’s Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958) or The Trumpet of Conscience (1967). We remember Malcolm X as an unparalleled orator, but after the collections of speeches there is only The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1964), an as-told-to story, an achievement shared with Alex Haley. Kenneth Clark’s work had a profound influence on Brown v. Board of Education, but as distinguished as his sociology was, nobody is rushing around campus having just discovered Clark’s Dark Ghetto (1965).

Baldwin said that Martin Luther King Jr., symbol of nonviolence, had done what no black leader had before him, which was “to carry the battle into the individual heart.” But he refused to condemn Malcolm X, King’s supposed violent alternative, because, he said, his bitterness articulated the sufferings of black people. These things could also describe Baldwin himself in his essays on race and US society. He may not have dealt with “this sociology and economics jazz,” as Harold Cruse complained of him in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967), but the reconstruction of America was for him, even in his bleakest essays, firstly a moral question, a matter of conscience. And at his best he simply didn’t need the backup of statistics and dates. When it came to The Fire Next Time (1963), the evidence of his experience, the truth of American history, he could take perfect flight on his own.

Nothing breaks the spell cast by James Baldwin in Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro. One of the things that makes Peck’s documentary so intense as a portrait of Baldwin, the engaged black writer, is that there are no talking heads, no one else making judgments or telling anecdotes about him or what he did. This is his public self, yet somehow deeply personal. Footage from fifty years ago has King, Malcolm X, Harry Belafonte, the head of a white citizens’ council, and J. Edgar Hoover talking to the camera. Yale philosophy professor Paul Weiss is a fellow guest on The Dick Cavett Show and doesn’t know what hit him. But the film’s attention is on Baldwin, his words above all others.

There is wonderful black-and-white footage of Harlem in the late 1950s and early 1960s when we hear Baldwin’s words about missing his family while he lived in France, but the film has little in the way of biography and it is not structured chronologically. For a documentary that hardly discusses his work—there is a shot of “Letter from a Region of My Mind,” the longer essay from The Fire Next Time, as it appeared in The New Yorker in 1962—Peck’s commitment to Baldwin’s voice is total. Not just anyone can hold your attention for two hours, which is perhaps why it does not matter how much the viewer does or does not know about James Baldwin.

Everything he says on camera is interesting, moving—his face so expressive, his diction original and precise. In his accent, his way of speaking in rapid clause clusters, he sounds like Leslie Howard, the romantic British actor of the 1930s.

Peck shows how riveting Baldwin’s writing is, like his speaking voice, “tough, dark, vulnerable, moody,” how inspired his ear. I Am Not Your Negro is divided into sections and so the screen will say, “Paying My Dues,” “Heroes,” “Witness,” “Purity,” and “Selling the Negro.” Maybe they are meant to introduce different themes, but each section is composed of the same elements, old and new clips of police confrontations, shots of city streets at night or river banks or views of skies as seen up through the trees of different places where the restless Baldwin traveled. Moments of the blues alternate with show tunes or Alexei Aigui’s music written for the film. It comes together as a general emotional intensity, largely because of the sheer personality of Baldwin’s language.

Advertisement

We have Baldwin, apologizing for sounding like an Old Testament prophet, but mostly we hear the actor Samuel L. Jackson in unhurried voice-over reading—or saying—long passages from Baldwin. He starts with a letter Baldwin wrote in the early summer of 1979 to his agent, proposing a book to be called Remember This House that would examine the lives of three black martyrs of the freedom struggle: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King. It would mean a journey back to the South and painful memories, concentrating on the years from 1955, when we first heard of Reverend King, to King’s death in 1968.

Peck tells us that Baldwin left only thirty pages of notes on the proposed book. (If the film has information the viewer needs, then Peck will impart it by means of typewriter noise producing white letters on a black screen.) Peck composed his script by drawing from some of Baldwin’s uncollected writings, maybe a bit from The Fire Next Time, as well as from two extended essays, No Name in the Street (1972) and The Devil Finds Work (1976), both included in Baldwin’s collected essays.

In the beginning of his film, Peck juxtaposes smoky black-and-white and Technicolor footage of Baldwin with high-resolution still photographs of Black Lives Matter demonstrations. A line from Baldwin heard later in the film is about how history is not the past; history is the present. Throughout, Peck makes connections between what is going on today and what Baldwin was protesting decades ago. His urgency had a point, and still does, the clip of a Ferguson, Missouri, riot says.

We hear lines from No Name in the Street, in which Baldwin is remembering the fall of 1956, when he was living in Paris:

Facing us, on every newspaper kiosk on that wide, tree-shaded boulevard, were photographs of fifteen-year-old Dorothy Counts being reviled and spat upon by the mob as she was making her way to school in Charlotte, North Carolina. There was unutterable pride, tension, and anguish in that girl’s face as she approached the halls of learning, with history, jeering, at her back.

It made me furious, it filled me with both hatred and pity, and it made me ashamed. Some one of us should have been there with her!… It was on that bright afternoon that I knew I was leaving France. I could, simply, no longer sit around in Paris discussing the Algerian and the black American problem. Everybody else was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.

Meanwhile, Jackson is speaking over those photographs of Dorothy Counts. We get to look into her face, and wonder how light-skinned she was, but we also can see clearly the faces of the white boys taunting her.

A few of the images may be familiar from other documentaries: deputies prodding King and Abernathy onto the pavement with batons, probably in Selma; a black man shoved up against a wall in Watts in 1965 gets in a blow at a surprised cop and is answered by three or four wildly swinging batons; they are swinging again in 1992, beating Rodney King, and not just for a few seconds of video either. Then there is Ferguson, Missouri. I Am Not Your Negro climaxes in what are probably mug shots of the Scottsboro Boys from 1931 that lead into recent images of police struggling with black men and assaulting black women. At another point, the faces and names of recent child victims of police killings fade in and out.

But one of the strongest features of Peck’s film is how much we see of ordinary white people and their violent resistance to integration in the 1950s and 1960s. In the course of the film, we see howling young white males, some mere boys, carrying signs painted with swastikas and tracking demonstrators; the National Guard escorting black school children through the gauntlet of angry faces in Little Rock. One of the most shocking sequences shows white men attacking what must be lunch counter sit-in protesters. It is color footage from 1960 or 1961. The violence has not been choreographed. It is sudden and raw. The hatred of black people is out there. The unguarded face of the South contrasts with images that play when Jackson is reading what Baldwin has to say about the myths and ignorance reinforced by American cinema.

Advertisement

The Devil Finds Work is a memoir of Baldwin’s childhood and youth in the form of his reflections on films that made an impression on him or that express something about how dangerous American innocence is when it comes to race. Jackson’s voice-over: “I am about seven. I am with my mother, or my aunt. The movie is Dance, Fools, Dance.” Suddenly, there she is, dancing away with her long legs in that 1931 film:

I was aware that Joan Crawford was a white lady. Yet, I remember being sent to the store sometime later, and a colored woman, who, to me, looked exactly like Joan Crawford, was buying something. She was so incredibly beautiful…and looked down at me with so beautiful a smile that I was not even embarrassed. Which was rare for me.

About his schoolteacher, Orilla Miller, as Baldwin recalled her in The Devil Finds Work:

She gave me books to read and talked to me about the books, and about the world: about Spain, for example, and Ethiopia, and Italy, and the German Third Reich; and took me to see plays and films, plays and films to which no one else would have dreamed of taking a ten-year-old boy…. It is certainly partly because of her…that I never really managed to hate white people—though, God knows, I have often wished to murder more than one or two….

From Miss Miller, therefore, I began to suspect that white people did not act as they did because they were white, but for some other reason, and I began to try to locate and understand the reason. She, too, anyway, was treated like a nigger, especially by the cops, and she had no love for landlords.

While we have been listening to Samuel Jackson, among the images we have also been watching are black-and-white photographs of black children at their school desks; a young Haile Selassie and his court; German children waving Nazi flags; film of Nazi book burnings; and lastly a still photograph of Miss Miller herself:

It is not entirely true that no one from the world I knew had yet made an appearance on the American screen: there were, for example, Stepin Fetchit and Willie Best and Manton Moreland, all of whom, rightly or wrongly, I loathed. It seemed to me that they lied about the world I knew, and debased it, and certainly I did not know anybody like them—as far as I could tell….

Yet, I had no reservations at all concerning the terror of the black janitor in They Won’t Forget. I think that it was a black actor named Clinton Rosewood who played this part, and he looked a little like my father. He is terrified because a young white girl, in this small Southern town, has been raped and murdered, and her body has been found on the premises of which he is the janitor…. The role of the janitor is small, yet the man’s face hangs in my memory until today.

And there is the scene of the janitor in his cell, on his bunk, filmed from above, the white faces looking down at him not visible to the audience. He cringes, sweats, and begs, a scene followed by footage from a silent film of 1927, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Baldwin’s words that because Uncle Tom refused to take vengeance he was no hero to him as a boy:

In the case of the American Negro, from the moment you are born every stick and stone, every face, is white. Since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose you are, too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6 or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians and, although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.

The photographs of the massacre at Wounded Knee are a surprise when they turn up.

Before Peck’s film ends, Richard Widmark will scream, “Nigger, nigger, nigger” in a clip from No Way Out (1950), a radical movie for its time, also starring Sidney Poitier, whom Baldwin does not blame for the ridiculousness of the films The Defiant Ones (1958), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), or In the Heat of the Night (1967). A scene from another Poitier film, Raisin in the Sun (1961), moves into Baldwin’s memoir of the play’s author, Lorraine Hansberry, and one of the last times he saw her on her feet, at a historic confrontation with Robert Kennedy, in June 1963. After a frosty farewell to the attorney general, Hansberry walked out of the meeting. Hansberry was thirty-four years old when she died of cancer. Baldwin remembers how young everyone was in those days, even Bobby Kennedy.

The use of clips is clever and they in themselves are often marvelous. We can hear a serious point being made about, say, the American idea of democracy as material abundance and the screen will fill with something like a mad dance at a picnic from the 1957 musical The Pajama Game. Or Doris Day could be singing along after some sharp analysis concerning America’s infantilism. The clips complement Baldwin’s way of moving from paradox to paradox.

But American identity and its consequences are not just commented on through Hollywood cliché. Part of what makes Peck’s film visually captivating is how unexpected some of his images are: a Department of Commerce film from the 1950s reminding retailers not to neglect the lucrative market of a new Negro middle class is somewhat bizarre, for example. Color footage of hangar-size supermarkets of the 1950s, of white boys as well as white girls at poolside beauty pageants—a world made possible, Baldwin would say, by the blacks we see working in the cotton fields and in the photographs of the lynched. Whites want to see the happy darkies of their food and appliance magazine and television ads, including Godfrey Cambridge singing the Chiquita banana song.

Some of the most moving footage in the film captures Baldwin in debate with William F. Buckley Jr. at Cambridge University in 1965. Peck leaves out Buckley’s side entirely. We don’t even see his face. Peck takes what he needs—just Baldwin speaking to the motion before the house, “Is the American Dream at the Expense of the American Negro?” It is footage that Peck returns to in his film, ending with the whole Cambridge Union Society on its feet for a startled Baldwin. Those white British students had probably never heard anyone say such things before. “What has happened to white southerners is much worse than what has happened to Negroes there.”

What I Am Not Your Negro cannot do is tell us much about Baldwin’s relationship to Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, or Martin Luther King Jr., because Baldwin couldn’t either, really. He met them, interviewed them, supported them, appeared with them, and loved them, he said. But he didn’t really know them, much as he identified with them, especially after their deaths. Baldwin was probably closer in temperament to Malcolm X, another son of the Harlem streets and renegade from his church, than he was to King.

Evers, an officer of the NAACP in Mississippi where he was investigating the murder of a black man in his county, was killed in 1963. “Then the music stopped, and a voice announced that Medgar Evers had been shot to death in the carport of his home, and his wife and children had seen that big man fall.” Malcolm X was killed in 1965. “The headwaiter came, and said there was a phone call for me.” King was killed in 1968. “The phone had been brought out to the pool, and now it rang.” The essay No Name in the Street is Baldwin’s attempt to describe, maybe even to cope with, his grief following the chances that were lost to the country after so many murders and so much political violence.

Many people had become more militant in the years between the March on Washington in 1963 and H. Rap Brown’s assertion in 1967 that violence was as American as cherry pie. I Am Not Your Negro reminds us of King’s opposition to the Vietnam War. Baldwin sometimes talked about the thin line between being an actor and a witness. As a survivor, he became a kind of keeper of the flame himself, but at a cost. He wrote, “‘Vile as I am,’ states one of the characters in Dostoevski’s The Idiot, ‘I don’t believe in the wagons that bring bread to humanity.’” It’s interesting that Peck has assembled his script not from the early essays, “classic” Baldwin, so to speak, but mostly from the spleen of his late work and articles that were once dismissed. You didn’t have to be a Marxist or a black cultural nationalist to be radical. Peck’s film, based on one of Baldwin’s unrealized works, is a kind of tone poem to a freedom movement not yet finished.

Twenty-five years ago, when Spike Lee released his film Malcolm X, which was based, in part, on the screenplay Baldwin had given up on around the time King was killed, articles appeared expressing worry that the film might incite black youth to violence. But Black Lives Matter can do without the macho. It represents a generation in agreement with Baldwin when he said that he no longer believed in the lies of pretended humanism. Activists today start where he ended up. At the core of his message was always the assertion that there was no Negro problem; there was the problem of white people not being able to see themselves, to take responsibility for their history, and to ask themselves why they needed to invent “the nigger.” “I am not a nigger. I am a man,” Baldwin says toward the end of the film, cigarette smoke escaping from him.

This Issue

March 23, 2017

What Trump Could Do

Fierce, She Got Outside the Moment