S.Y. Agnon (1888–1970), who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1966, is the one modern master among writers of Hebrew fiction. Jeffrey Saks has undertaken a heroic task in assembling the Agnon Library, using existing translations, which generally have been revised, and commissioning English versions of previously untranslated books. It is not quite a complete works because some books could not be included for reasons of copyright or on other grounds. The most unfortunate omission is Agnon’s modernist masterpiece, Only Yesterday (1945), a wrenching and richly inventive novel about a naive young Zionist’s failed attempt to take root in the land, which unfolds in Jaffa and Jerusalem in the early years of the twentieth century.

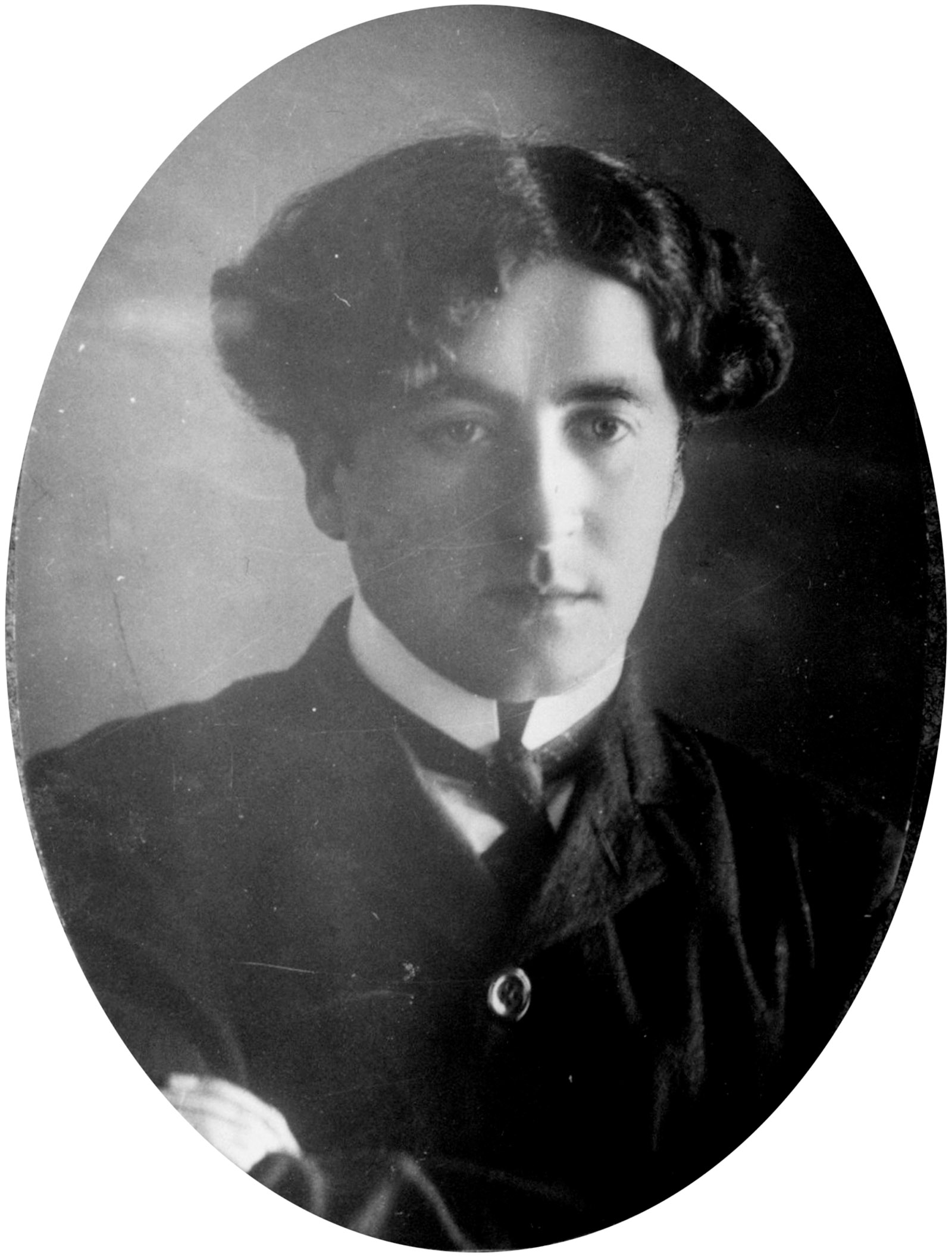

Shmuel Yosef Agnon (his original family name was Czaczkes) was born in Buczacz, a town of about 15,000, over half of whom were Jews, that at one time belonged to Poland, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from the late eighteenth century until the end of World War I, and is now in western Ukraine. In an Orthodox home, under the supervision of his learned father, he was given a thorough education in the classic Jewish texts, from the Bible with its medieval Hebrew exegetes to the Talmud, and he would draw on this background extensively throughout his career. But his family also engaged a German tutor for him, and he read Goethe, Schiller, and other German writers with his mother. The adolescent Agnon was drawn to Zionism, a movement then less than ten years old, and in 1908, when he was nineteen, he immigrated to Palestine.

Like most of the young Zionists of that era, he proceeded to abandon the religious practice of his childhood. The Hebrew stories he began to publish in Palestine quickly attracted attention, the first being Agunot (“Abandoned Women”), a story of unhappy lovers written as if it were a folktale, from which he took his rather somber new name.

In 1913, for reasons that remain obscure, he moved to Germany. Whether or not he intended a long stay, he was caught there by World War I, and he did not return to Palestine until 1924, married and with two children. He settled permanently in Jerusalem and returned to Orthodox observance. He appears to have used his German years to immerse himself in European culture while continuing to write Hebrew fiction. He also did some teaching at Franz Rosenzweig’s Frankfurt Lehrhaus, collaborated with Martin Buber in collecting Hasidic tales, and began a lifelong friendship with Gershom Scholem, the great historian of Jewish mysticism.

Agnon is in some respects an anomalous modernist. Early on, he had an affinity for European gothic writers, and gothic motifs such as the Dance of Death, ghostly brides, and revenants occur in many of his stories. He might, one conjectures, have been drawn to Thomas Mann’s recurrent theme of the conflict between eros and the calling of the artist and to Mann’s use of narrative leitmotifs. The dreamlike surrealist stories Agnon began to write in the 1930s are in some ways reminiscent of Kafka, though in one interview he vehemently denied any connection, saying that he had only one or two books by Kafka on his shelves and that the main thing for him as a writer was what the Holy One inspired in his heart. With characteristic slyness, he added that his wife, on the other hand, owned Kafka’s collected works.

In a 1916 letter to Salman Schocken, the department store magnate and, later, publisher who became his patron, he expressed his profound admiration for Flaubert, whom he would have read in German translation. This was a writer, he said, “who mortified himself in the tent of art,” pointedly substituting “art” for “Torah” in a well-known rabbinic idiom. Flaubert was his model for the painstaking devotion to the writer’s craft—Agnon assiduously revised much of his work, and in the years immediately after World War I he transformed some of the effusive stories of his first decade of writing into beautifully disciplined prose. I suspect that he also learned from Flaubert the narrative technique of free indirect discourse, in which a character speaks through the voice of the narrator, which he frequently used as an instrument of psychological characterization.

Despite all this, Agnon often wrote as a traditional teller of Hebrew tales for whom the corpus of European literature was remote. In one of his stories he refers to “Homer, the master [rav] of the poets of the Gentiles,” using paytan as the word for “poet,” a term that usually designates a composer of liturgical verse. The stylistic pretense here is that Homer belongs to an unfamiliar realm, though in Agnon’s haunting novella Betrothed he has an important part in the protagonist’s fateful passion for the sea and the Mediterranean world of origins. Scholem, in an interview on Israeli television a few years after Agnon’s death, was asked by the critic Dan Miron what he made of Agnon’s Orthodoxy. Scholem shrewdly responded that for Agnon art was the crucial consideration and that he was religious because it served his purposes as an artist.

Advertisement

His religious identity is clearly inseparable from the unique path he chose as a Hebrew stylist, and that in turn poses a constant challenge for translating his work. “My language,” he writes, “is a simple language, the language of all the generations that preceded and of all the generations to come.” His Hebrew is essentially the Hebrew of the early rabbis, which means the Hebrew of the Mishnah and the Midrash compiled early in the Common Era, with at some moments a trace of Yiddish inflections and occasional limited concessions to the modern language. His hyperbolic invocation of “the language of all the generations” reflects his classicizing bent: for him, rabbinic Hebrew is as living and subtly expressive a vehicle as it was eighteen hundred years ago, and by using it he means his works to be similarly long-lasting.

It is scarcely the language of the most recent generation of Hebrew speakers. When I taught a graduate seminar on Agnon’s novellas at Berkeley a few years ago, several of the students were young Israelis with whom I had to spend some time in class explaining rabbinic terms and idioms and identifying the allusions to biblical and later texts. Agnon’s Hebrew, of course, is wonderfully apt for all the stories and novellas that use the device of a traditional teller of tales—who often proves to be ironic or subversive beneath the mask of tradition. In the novels and stories that deal with people in modern settings, the prose often has the effect of generating pervasive ironies because of the cultivated discrepancy between the Late Antique coloration of the Hebrew and the world of the characters, often characterized by secular values, the ambiguities of sexual freedom, and the ravages of modern war.

In view of the distinctive charm and force and the literary echoes of this writing, I sometimes have suspected that Agnon may be one of those writers, like Pushkin, who are absolutely brilliant in the original and don’t come across very well in translation. But this could not be altogether true. Walter Benjamin, reading Agnon in the German translations of his early work in the 1920s, was convinced that he was a great writer. Edmund Wilson, the first American critic to draw attention to him, came to the same conclusion in an essay for The New Yorker in the late 1950s.

The many translators Jeffrey Saks has gathered for his series by and large respond creditably to the challenge, though there is, understandably, some unevenness. Even a single ill-considered word-choice can throw a translation out of kilter. In one story, when a ragged stranger appears at a synagogue in Buczacz, we realize before long that he must be the Elijah of Jewish folklore. Again and again in this English version, he is called “the vagrant,” but the Hebrew heilekh means no such thing. A heilekh is a wayfarer, a traveler on foot, with none of the negative connotations of vagrancy, which would scarcely suit the harbinger of the messiah. Elsewhere, translations are at points marred by errors in English idiom or grammar (even “like” for “as,” or “who” for “whom.”) This is unfortunate because Agnon’s Hebrew is meticulously correct and exhibits perfect pitch in the rabbinic idiomatic usage it has adopted. These are, however, no more than small flaws.

The anomaly of Agnon as a modernist is manifested in the two quite different aspects of his fiction. Many of the novels and stories with a modern setting have a mastery of form that shows Agnon as a peer of Mann, Hermann Broch, and modernists such as Faulkner and Joyce whom he may or may not have read. (When I visited him as a student at his home in 1960, there was a copy on his desk of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, just then translated into Hebrew.) But there are also works, including one important novel, A Guest for a Night (1941), that seem loosely associative, anecdotal, episodic. In texts written by some writers of the Jewish Diaspora, the critic Benjamin Harshav writes,

each detailed observation is treated for its autonomous value. Every detail is taken out of its narrative chain and observed close up; it does not lose the reader’s interest, for it belongs to one total universe, which endows each detail with rich meaning and depth.

Harshav links this kind of discourse with traditional methods of Talmud study as they have been “folklorized” in Yiddish-speaking culture, and he finds its aftermath in the writings of Freud, Kafka, Saul Bellow, and others.

Advertisement

In some cases, Agnon uses such episodic discourse to good artistic effect, as in A Guest for the Night, which doesn’t have much of a plot but nevertheless creates a powerful portrayal of the devastation wreaked by World War I on the narrator’s hometown, to which he has come from Jerusalem for an extended stay and where he finds a world of maimed bodies and people with the bleakest prospect for any collective future. He calls the town, here and elsewhere, Szybusz, an obvious substitute for Buczacz, which sounds like a Polish name but in Hebrew means “breakdown” or “distortion.” In other instances, the cultivation of Jewish discourse seems a little self-indulgent and can be annoying to the reader, as in his posthumously published novel, In Mr. Lublin’s Store, set in Leipzig during World War I.

Much of his longer fiction, however, follows the patterns of the European art novel, as do his exquisitely wrought novellas—And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight (admired by Walter Benjamin), Hill of Sand, In the Prime of Her Life, Betrothed, and Edo and Enam. The most striking example of Agnon as a “European” writer is the novel A Simple Story (1935), set in Szybusz at the beginning of the twentieth century. Like many of Agnon’s stories and novels, it is a tale of doomed love. Hirshl, the passive protagonist, is hopelessly in love with his poor cousin Bluma Nacht—“night flower” in both German and Yiddish—who has come to work as a servant in his parents’ house. As prosperous bourgeois shopkeepers, however, the parents arrange a marriage for him with the daughter of an affluent farmer. After the wedding, Hirshl’s obsession with Bluma continues to grow and his mind deteriorates until he has a psychotic breakdown, brilliantly rendered by Agnon. In the end, he returns to sanity and reconciles with the wife his parents have chosen for him, but it is a reconciliation suffused with bitter irony, for it entails succumbing to their world of coin-counting, social conventionality, and complacent materialism.

A Simple Story is the most Flaubertian of Agnon’s novels, and in keeping with its French model, it is the most perfectly constructed. He often draws on Flaubert’s technique of free indirect discourse to represent Hirshl’s consciousness and his habitual failure to recognize the real nature of his own desires. Also Flaubertian is the reiteration of motifs—roosters, geese, cigarettes, coins, and much else—that have their own fraught presence and help pull the novel tightly together. And Agnon surely would have sympathized with Flaubert’s animus against the bourgeoisie. All the bourgeois figures in the novel are Jews, but they are also preeminently European, and this is a thoroughly European novel. Written between the two world wars, it feels rather like a nineteenth-century European novel. By this time, Agnon had already begun writing experimental fiction, but his major modernist novels and novellas still lay ahead.

Readers who make their way through Jeffrey Saks’s series will see that Agnon is often deeply immersed in the ancestral world of piety. He sincerely loved the sacred books that were its foundation, and he shows genuine reverence for his forebears’ devotion to God and Torah. Nevertheless, the pious impulse in his writing is not always what meets the eye, and it is well to keep in mind Scholem’s observation that the religiosity ultimately served Agnon’s aims as an artist.

A case in point is the large cycle of stories A City in Its Fullness, edited by Agnon’s daughter after his death. The stories, some folkloric, many realistic, all take place in a Buczacz of centuries past. Agnon wrote them relatively late in life, brooding over the fate of his hometown, where almost the entire Jewish population was slaughtered on a single day by the Nazis. Though the stories are from time to time punctuated by angry denunciations of the killers, one must agree with the American scholar Alan Mintz that for Agnon “the truest response to the Holocaust is to create literarily the fullness of Jewish life before that dark shadow was cast.” Several of the early stories in the cycle are virtually hagiographic, celebrating prodigies of devotion to Torah scholarship and to the scrupulous observance of all the minute details of rabbinic law.

As the book progresses, however, we begin to encounter shocking tales of vindictiveness, greed, gluttony, and the heartless exploitation of the helpless poor. Even a story that ostensibly extols an extreme act of piety, about a man who dies of hunger in the forest, though he has food, because he refuses to eat in the absence of water for the ritual washing of hands, makes piety look like craziness. A City in Its Fullness, at first glance a loving commemoration of the ancestors whose descendants were murdered, turns out to have a subversive undercurrent, as in much of Agnon. As an artist he was too deeply committed to an unblinking vision of things as they are to sustain an aura of reverence.

“In the Forest and in the Town,” a story first published in 1938 and not yet included in the Agnon Library (it should be translated in one of the two remaining volumes), offers an instructive clue to Agnon’s larger enterprise. The first-person narrator, an adolescent, has abandoned his Talmud studies to go wandering every day in the forest outside his town, presumably Buczacz. He takes with him a copy of the Hebrew Bible but informs us that he is reading the Prophets and the Writings, possible sources of poems and stories, and not the Torah, the compendium of laws and the primary point of departure for the Talmud. He is the artist as a young man.

There is an obvious antithesis between the town, where people constantly worry about making a living, and the forest, which is represented as both edenic and wild. (The use of opposites is also suggested in the Hebrew words for “forest” and “town,” which are anagrams of each other.) In this forest, however, there lurks an escaped multiple murderer called Franciszek. That the killer bears the same name as the gentle saint who spoke to the birds is one of several reversals of received notions in the story.

The narrator’s parents are, of course, alarmed that their son should insist on continuing his visits to a dangerous place, but he is not in the least frightened by the prospect of encountering the murderer, which as readers we sense will occur. First, however, he meets an enigmatic old man who decides to tell him—their conversation would have to be in Polish—what happens in the initial chapters of Genesis, concluding with “Abel rose up and killed Cain. Of course, Cain could have killed Abel, but he who must die, dies.” The narrator makes no comment on this startling switch of killer and victim, though it will be recalled at the end of the story.

When the narrator finally comes upon Franciszek, the two speak amicably, and the escaped murderer offers the young man a swig of schnapps from the flask fastened to his belt. The narrator accepts, but before he drinks, because he is, after all, an observant Jew, he pronounces in Hebrew the requisite blessing, which ends with the words “for everything comes about through His word.” Franciszek asks him to translate and then has him repeat the words in Hebrew, shehakol nihyeh bidvaro. He ponders what the young man has told him the words mean, repeatedly muttering, “Maybe it’s so.” Then he tries to parrot the Hebrew, managing only a mangled version of the first word—tchokl. The narrator goes home, careful to reveal nothing of his meeting in the forest.

After a time, Franciszek is captured and subsequently led out for a public execution with much of the town’s population present. The townspeople show mixed feelings toward the condemned man, some wanting to see him killed, others finding themselves strangely sympathetic toward him. “But since man’s imagination,” the narrator strategically remarks, “cannot match the attribute of cruelty he possesses, they accepted despite themselves the verdict of the judges.” The narrator ends up standing close to the gallows, and as the noose is about to tighten around Franciszek’s neck, he is heard to utter a single word, tchokl. The other bystanders are perplexed, but the narrator thinks he understands: when the killer first heard the declaration “for all comes about through His word,” he wondered whether it was true; now, at the moment of death, he accepts his fate, affirming that even the cycle of violent crime and inexorable punishment is part of a divine plan.

The story turns conventional ideas upside down. The serial killer is a kind of rude philosopher; everyone, as the narrator observes elsewhere in the story, has the potential to be a killer; Abel was fated to murder Cain, though it could have been the other way around. In the forest, the narrator, manifestly Agnon’s surrogate, performs a ritual gesture prescribed by religious law in reciting the blessing, but it is the killer rather than the young Jew who thinks hard about the meaning of the words. In the wild beyond the town, a secret pact is sealed between the future artist and the criminal.

That, I would contend, is the underlying paradox of Agnon’s multifaceted project as a writer. He often presented himself to his readers and to the public eye as a modern avatar of Jewish tradition, writing in the very Hebrew in which it had been fashioned, expressing reverence for its sages and saints. But he also had a sense that there was a kinship between the artist and the outlaw. Agnon certainly cherished the knowledge that could be attained from sacred texts, and also, as an autodidact and the friend of modern scholars, he evinced some admiration for secular scholarship as an instrument of knowledge.

Yet he conceived art—as becomes clear in Shira, his posthumously published novel about eros and art, art and disease—to be the vehicle of a more profound, more perilous and painful order of knowledge than could be attained through any institution of learning, pious or secular. Endorsed by a community, whether in a yeshiva or a research library, such learning could lead one only so far. It is, finally, in his view, the artist who is prepared to take the dangerous last step into the forest where ultimate contradictions must be confronted, where he must put himself beyond the pale of received values, like his secret brother, the outlaw.