On All Hallow’s Eve of 1517, Martin Luther, Augustinian friar and professor of theology, posted a broadsheet on the faculty bulletin board of tiny, provincial Wittenberg University in the German state of Saxony (which happened to be the door of the church attached to the local lord’s castle). The poster was no Halloween prank; it proclaimed, according to academic custom, his willingness to debate a series of propositions in public. Although he also sent copies of the same broadsheet to important statesmen, churchmen, and academics outside Wittenberg, no one seems to have taken up his challenge to a formal discussion. His propositions were too explosive for that; in blunt, forceful language, they questioned the basic beliefs of the church to which, as a Hermit of Saint Augustine, he had vowed his obedience.

Luther would say that his life’s turning point came two years later, when he had a sudden revelation about the nature of Christian salvation. For his contemporaries, however, the posting of his ninety-five theses in 1517 set off the spark that ignited the Protestant Reformation, and the Reformation in turn marked a fundamental stage in the forging of a collective German identity. To mark the event’s five hundredth anniversary, the Federal Republic of Germany has sponsored a series of Luther celebrations at home and abroad, which began in the fall of 2016 and continue throughout 2017. They include an ambitious series of Luther-themed exhibitions in the United States: major shows in Minneapolis and Los Angeles, with smaller versions of the Minneapolis extravaganza in New York and Atlanta, all providing a fresh, insightful view into Luther’s life and times and the vast, unpredictable forces his rebellion unleashed.

The exhibition catalogs—two impressive five-hundred-page volumes shared by Minneapolis, New York, and Atlanta, and a separate work for Los Angeles—cover a vast range of topics: Martin Luther and Martin Luther King, Martin Luther’s latrine, Lutherans in North America, Luther in Communist East Germany, the unintended consequences of the Reformation. The intensity of their focus is relieved by clever, colorful charts and a bountiful complement of illustrations. It is impossible, given our own recent past, to ponder the Reformation without also pondering its darker legacy of religious warfare, anti-Semitism, and lingering mistrust between Catholics and Protestants, German East and German West; and these are issues the catalogs face head-on.

Yet what drove the friar and his contemporaries to their drastic actions were ideas of transcendent beauty, including the profound inner music behind the cadences of Luther’s oratory and the stirring hymns that set his spiritual armies on the march. To understand this complicated, superbly talented man, and to make the most of the Luther exhibitions, it helps to have a good biography on hand, and Lyndal Roper’s Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet provides expert and spirited guidance. So, in a more specialized way, does Andrew Pettegree’s Brand Luther, a fascinating study of Luther’s pioneering relationship with the printing press that is especially helpful for understanding these exhibitions dedicated in large measure to books and other mass-produced printed works.

The Protestant Reformation took hold where it did and when it did for a variety of reasons, beginning with the blazing personality of Martin Luther himself. Strictly speaking, he was not a monk, though he is often described as one: he was a preaching friar who belonged to the largest Catholic religious order of his day, the Hermits of Saint Augustine. Rather than spending their time, as monks did, in secluded prayer in a monastery, the Augustinians lived in cities and moved from place to place. They trained to communicate the Christian message in what for the time was a revolutionary new style: borrowing techniques from the orators of classical antiquity and from contemporary preachers who gave sermons in colloquial languages rather than Latin, they appealed openly to the emotions of their hearers.

Friar Martin focused his ire (and most of the ninety-five theses) on one particular practice of the institutional church: the sale of indulgences. These papal dispensations, confirmed by paper certificates, grew out of a traditional medieval conviction that prayer, repentance, good works, and pilgrimage could atone in some measure for sin. It was even possible to do penance for someone else, as Luther did during his stay in Rome, kneeling on the steps of the Holy Stairs at Saint John Lateran to earn an indulgence for his grandfather. Giving alms or endowing a church could also earn remission from sins, reducing the amount of time a person would need to spend after death in the uncomfortable realm of Purgatory, where, in late medieval Christian belief, human souls were gradually cleansed of their iniquities until they were pure enough to enter the Earthly Paradise, there to await final admission to Heaven on Judgment Day. By the late fifteenth century, however, remission from sins could simply be purchased from a papal agent, for oneself or for another person, whether alive or deceased.

Advertisement

The sale of indulgences became an industry only in Luther’s own lifetime and in his own lands, put into place by the “warrior Pope” Julius II and the Augsburg banker Jakob Fugger. After 1506, pope and banker directed the revenue from German indulgences toward the rebuilding of Saint Peter’s in Rome. “Martin Luther: Art and the Reformation,” a monumental exhibition that took inspired advantage of the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s spacious galleries, and “Word and Image: Martin Luther’s Reformation,” a scaled-down version of the Minneapolis show tailored to the intimate spaces of the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, displayed specially-made “indulgence chests,” iron-bound coffers with handy coin slots, the equivalent of immense, armor-plated piggy banks.

These heavy wooden boxes with their multiple locks demonstrate the extent to which the German states were exporting huge quantities of metal to Rome and receiving printed slips of paper in return, exchanging material wealth for the equivalent of checks that drew on the currency of heaven rather than earth. Jakob Fugger took a 3 percent cut—in coins, not release from Purgatory—on every shipment south. Is it any wonder that the man who finally pulled the plug on this improbable trade knew a thing or two himself about the value of metal?

In later life, in one of his famous dinner-table conversations, Martin Luther claimed to come from modest origins, and indeed his father, Hans Luder, ended his life in financial trouble. But in 1483, when Martin came into the world, the Luders were a prosperous family of copper smelters living in the foothills of the ore-rich Harz Mountains. Archaeological remains excavated from the family compound in Mansfeld, where Martin spent his childhood, tell a tale of affluence.

The exhibitions in Minneapolis and New York included fine glassware among the beer steins, as well as gold sequins and other ornaments from the Luder girls’ dresses, buried, perhaps, when plague struck the city in 1505 and killed two of the Luder boys. Dorothea Luder, Martin’s sister, had to sacrifice a monogrammed gold buckle along with her belt for fear of contagion. The family’s rubbish pit also yielded copper slag and an abundance of pig and goose bones, further signs of the household’s prosperity. Hand-rolled clay marbles may have been Martin’s own, along with bowling pins made of knucklebones with a metal weight sunk into one end.

To a remarkable extent, as these exhibitions reveal, Luther’s world, and Luther’s Reformation, revolved around metal. The silver, copper, lead, and iron mined from the Harz Mountains and smelted in small-scale factories like Hans Luder’s copper works took up only a corner of an international market in which Jakob Fugger was one of the most aggressive participants. Fugger may have been shipping coins by the cofferful to the pope in Rome, but metal was also flowing into his own treasury from his silver and copper mines in Tyrol and Bohemia.

Almost every aspect of these impressive exhibitions intersected with metal somewhere. Friar Martin, for instance, probably stuck his theses to the Castle Church door using glue or wax rather than expending precious metal to nail them. German expertise with metallurgy was so renowned in Renaissance Europe that Italian jewelers sought technical advice from their German colleagues.

At the same time, German artists absorbed lessons in style from Italians, so that Hans Reinhardt and Wenzel Jamnitzer became as internationally renowned for their gold- and silversmithing in the early sixteenth century as Albrecht Dürer was for his copperplate engraving, all three of them joining incomparable German craftsmanship to Italian-inspired flair. The metal typefaces that broadcast the arguments of Reformers and Roman traditionalists back and forth across Europe originated among German metalworkers, and so did the glittering weapons and guns that would soon be carrying out the butchery of new and vicious religious wars. The first treatise on metallurgy was written by an Italian, Vannoccio Biringuccio, but he gained his experience with lead and silver at the Fugger mines in Tyrol.

And metals, of course, meant money. Between 1508 and 1524, Fugger’s firm not only managed the business of indulgences for the German states, but also struck the coins produced by the papal mint in Rome, as Luther may well have learned (or known already) when he visited that city in the winter of 1510–1511. He certainly focused on money in his forty-fifth thesis:

Christians are to be taught that he who sees a needy man and passes him by, yet gives his money for indulgences, does not buy papal indulgences but God’s wrath.

And his forty-eighth:

Advertisement

Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting indulgences, needs and thus desires their devout prayer more than their money.

And his fiftieth:

Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the indulgence preachers, he would rather that the basilica of Saint Peter were burned to ashes than built up with the skin, flesh, and bones of his sheep.

On an epic scale in Minneapolis, an expansive scale in Los Angeles, and an intimate scale in New York (I was unable to see the exhibition in Atlanta), the aesthetic refinement and technical mastery of German metalwork stood out in all its dazzling virtuosity. Hans Reinhardt’s intricately layered, delicately textured medal depicting the Holy Trinity is probably the most complex example ever created of this popular Renaissance art form. Albrecht Dürer’s triumphant series of engravings from the first decade of the sixteenth century—The Knight, Death and the Devil, Melencolia I, and Saint Jerome in His Study—use black lines on white paper to suggest every possible nuance of light and shadow, along with the dense fur of Saint Jerome’s contented lion, the loose, mangy skin on the ribs of Death’s skinny horse, sunbeams streaming through the glass panes of Saint Jerome’s window, and the ambiguous sunrise in the distance beyond a dark-complexioned Melancholy (Greek for “black bile”). Los Angeles displayed an opulent casket by the Jamnitzer workshop, an enormous piece of jewelry in itself: enameled, engraved, studded with saucy sphinxes and tiny lions, gleaming in silver, gold, and royal blue, with pull-out drawers.

German artists excelled in other media as well. Los Angeles displayed two wooden sculptures by Tilman Riemenschneider of Würzburg: a tender Virgin Mary and a Saint Matthew whose sensitive hands make one wonder what the sculptor’s own must have looked like. (The story that Riemenschneider’s hands were broken by Lutheran iconoclasts is a nineteenth-century myth, one of many vicious rumors spun by both sides of the Reformation.) Priestly vestments of wool and damask (a mixture of wool and silk) hung in elegant folds in New York and especially Minneapolis, embroidered in wool, silk, and metallic wire of silver and gold. Minneapolis and Los Angeles displayed whole suits of armor, the wasp-waisted corrugated panoply of Prince Wolfgang of Anhalt-Köthen standing out among breastplates forged to accommodate multiple chins and beer bellies.

What drove Friar Martin to post his theses, however, was a spiritual insight, a realization so overwhelming that it prompted him to alter his name from Martin Luder to Martinus Eleutherius—“Martin the Free.”* The Christian hope for eternal life, he had come to believe, was a divine gift that no human being, no matter how virtuous, could ever deserve—there was no penance for sin that could truly merit divine indulgence. Salvation, therefore, was not a reward, but an outright gift from God, bestowed out of the sheer abundance of his love for his creation.

For years Friar Martin had chafed at the idea of a judgmental God who lay in wait to punish sinners. But now a phrase that had always irked him, “the righteousness of God,” struck, as he would later say, “like a thunderbolt”:

It is written, “He who through faith is righteous shall live.” There I began to understand that the righteous [person] lives by a gift of God, namely by faith. And this is the meaning: the righteousness of God is revealed by the gospel…with which the merciful God justifies us by faith…. There a totally other face of the entire Scripture showed itself to me.

His thirty-seventh thesis asserted:

Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

He posted his theses, as the broadsheet declared, “Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it.”

Luther’s message swiftly found followers, especially in the German states: on the spiritual level with his doctrine of justification by faith, and on the practical level with his attack on the alliance between religion and capitalism that had turned remission of sins into a commercial enterprise. He survived the religious and political firestorm he ignited not only because of his courage and eloquence, phenomenal though they were, but also because the local sovereign, Elector Frederick III of Saxony, decided to side with his renegade friar rather than his bishop. Nicknamed “the Wise,” Frederick was as shrewd as he was pious. Over the years he had amassed a staggering number of saints’ relics, some 18,970 by 1520, which he displayed once a year in Wittenberg Castle, each one lovingly installed in an opulent, beautifully wrought metal reliquary (several of which were on view in Minneapolis).

Pilgrims flocked to see the collection and left their offerings of coins and valuables, ensuring that metal continued to flow into Wittenberg rather than Rome, and keeping Frederick free, unlike his bishop (and his nominal liege lord, the Holy Roman Emperor), of colossal debts to Fugger. Frederick the Wise never entirely sided with Luther’s revolution (he remained Catholic), but neither did he oppose it. And at one crucial juncture in 1521, he saved Luther’s life by hiding him away in Wartburg Castle disguised as a bourgeois layman named “Junker Jörg.”

Luther’s bishop, Albert of Brandenburg, archbishop of Mainz, was one of his first and most powerful detractors. Albert received one of the first copies of the ninety-five theses and reported on them to Pope Leo X. The archbishop had good reason to worry: he was responsible for the sale of indulgences in his metal-rich diocese, and he was hopelessly in debt to Jakob Fugger, who had financed his campaign for office. The pope, duly informed, summoned Friar Martin to Rome to answer for his actions, but it was soon clear that the renegade had no intention of playing into the pontiff’s hands.

Eventually an interview was arranged in Augsburg in 1518, in conjunction with the meeting of the electors of the Holy Roman Empire, the very German statesmen who faced the spreading religious rebellion among their citizens. From the papal point of view, Cardinal Tommaso de Vio da Gaeta (usually known as Cajetan, “the Gaetan”) must have seemed like the ideal man for the job: the former head of the Dominican order and one of the most influential prelates of his era, he was also a trained inquisitor under instructions to make Luther recant or to arrest him and drag him back to Rome.

The meeting between the friar and the cardinal took place in Fugger’s Augsburg house. Cajetan was a master of Scholastic reasoning, the elaborate medieval system of theology, thought, and rhetoric that had developed with the first universities—the very system that new universities like Wittenberg and orders like Luther’s Augustinians were dedicated to overthrowing for new kinds of inquiry and expression. Luther hated Scholasticism and its pedantry at least as passionately as he hated the mixing of religion and business, and few people have ever hated with Luther’s white-hot intensity. Gaunt, ailing, and urgently aware that he might be risking a death sentence, he stood his ground against the cardinal, who lectured him about a few of the theses and let him leave Fugger’s house untouched. The cardinal realized that it was too late for an arrest to solve the problem. Luther already represented a movement. He was not an isolated heretic who could be whisked away in secret.

If he had written little before, now Luther went into overdrive, proclaiming his theology in torrents of prose and poetry in both Latin and German, and spreading his ideas as widely as the printing press could reach. He forged two indispensable partnerships, one with his colleague Philipp Melanchthon, the professor of Greek at Wittenberg, and one with Elector Frederick’s court painter, Lucas Cranach. Melanchthon gave the burgeoning movement its intellectual rigor, and Cranach, together with Luther, turned tiny, remote Wittenberg into a center for publishing; his own workshop became the crucible of Lutheran art.

Cranach already managed a sizable enterprise from his house in the center of Wittenberg, producing portraits, altarpieces, allegories, and history paintings for private patrons as well as for Elector Frederick and his family. His state portraits show that Luther was supported throughout his life by a series of imposingly large men: Frederick the Wise, his brother and successor John, and John’s son John Frederick, whose wife, the slender, cat-eyed Sibylle of Cleves, captivated Cranach. One portrait displayed at the Morgan Library shows the veins beneath her porcelain skin; in another painting, of a hunting expedition that never happened, Sibylle, in her pearl-studded dress, shoots off a massive arquebus with the aplomb of a Renaissance Annie Oakley.

As the Reformation took hold, Cranach continued to work for Catholic patrons as well as Lutherans, but his efforts for Luther were inspired and revolutionary. Quickly the painter and the friar devised a standard format for their publications: quarto books (the size of a large modern paperback) with titles in crisp Gothic letters above a large woodcut image from the Cranach studio, tailored to the new Lutheran vision of heaven and earth. (One popular theme was the contrast between life under the old law and life under the rule of grace, where the old law is both Jewish and Catholic.) Even before Luther’s impassioned words could sink in for readers of his tracts, the black-on-white clarity of their visual presentation already cut as sharply as a sword.

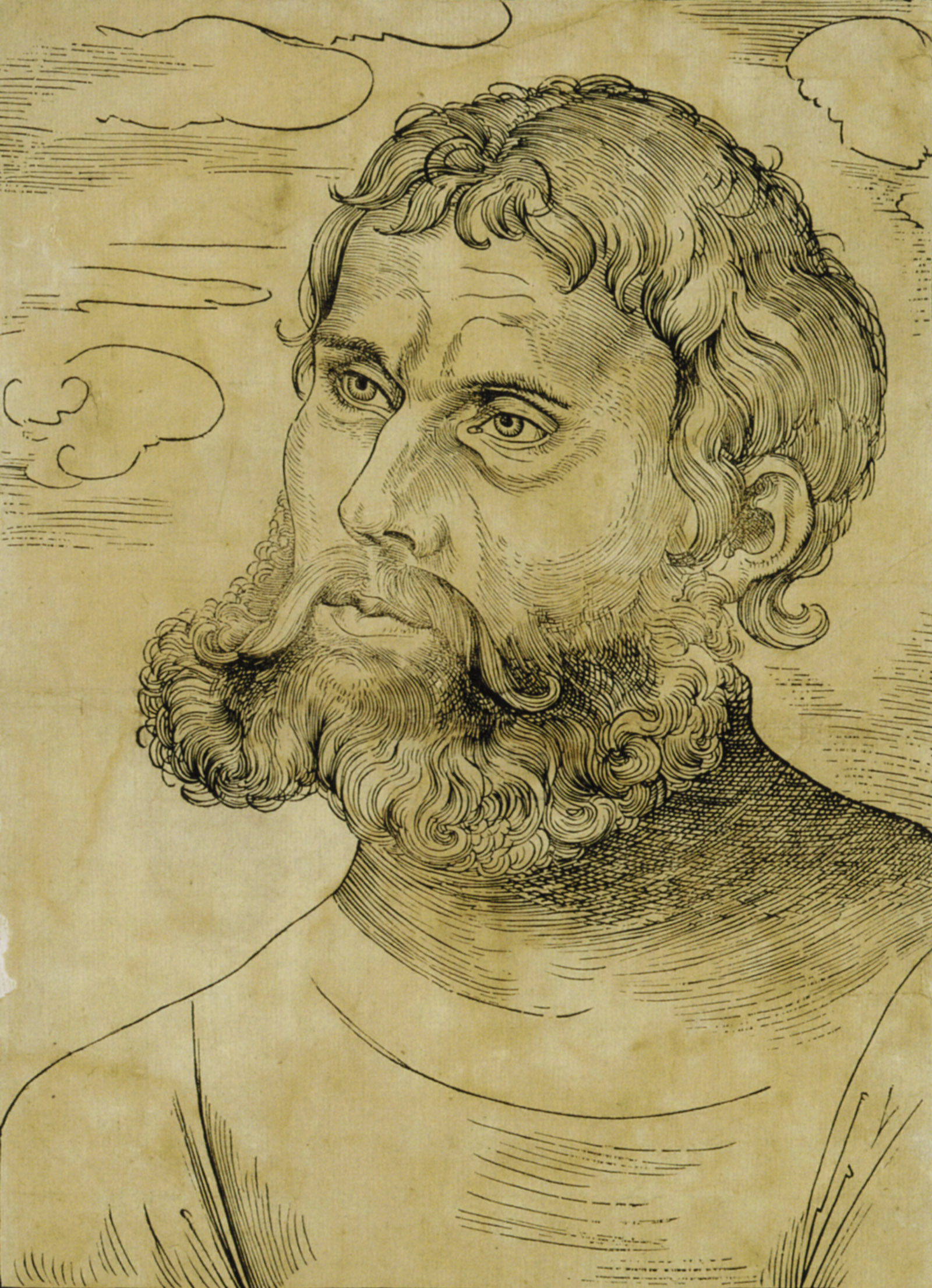

At the same time, Cranach worked on the image of Luther himself. His first portraits of the Reformer show a thin, clean-shaven friar with hollow cheeks, an Augustinian tonsure, a sunburst behind his head, and a look of blazing concentration. As the years go on, he grows in bulk and authority, culminating in the deathbed portrait of a man finally at peace.

Satires, cartoons, and broadsheets followed closely on the stream of tracts and Luther’s translation of the Bible for the first time into German (illustrated by Cranach), with the Protestants almost always striking a clever blow one step ahead of their adversaries. There was nothing refined about Martin Luther’s sense of humor; if he called the world a sewer (cloaca) in Latin, in German he called it (and many of its phenomena) a pile of shit. Freed from his Augustinian vows (which had never included poverty), he continued to live in the same convent in a bachelor’s chaos until 1525, when he married the runaway nun Katharina von Bora.

Luther soon discovered the range of his wife’s talents: she cleaned up the sprawling house, brewed excellent beer, set up a pig farm and a hospital, entertained a host of students at dinner, bore him six children, and cared for four orphan children besides. Archaeological excavations of the Luther household reveal glassware from Venice, broken beer steins, and an abundance of pig bones. For his part, Cranach developed an image of Martin and Katharina as the ideal Christian couple through a new series of portraits, small enough for faithful Lutherans to keep at home, complemented by huge, less expensive, paper images of Luther and Melanchthon that could be posted on walls, presenting both the portly Reformer and the weedy professor as Titans.

Roper’s biography and the exhibition catalogs squarely confront the legacy of Luther’s searing hatred, of Jews especially, but also of papists, Calvinists, and anyone else who failed to see the truth as he did. But what these impressive exhibitions show most of all is an inspired man with an earnest mission in a complex world of money and alchemy, sublime art and music, and burning questions about how faith should fit into a society that had burst its immemorial boundaries.

-

*

Because “Luder,” the family name, could mean “loose woman,” the ninety-five theses already spell Friar Martin’s name as “Lutther.” When, after a few months, Martinus Eleutherius reverted to a more normal name, it was to our familiar “Luther.” ↩