The writings of Donald Judd are triumphantly matter-of-fact. The sculptor, who died in 1994 at the age of sixty-five, was decisive even about his second thoughts and doubts. “Cocksure certainty and squirming uncertainty are both wrong,” he once wrote. “It’s possible to think and act without being simple and fanatic and it’s possible to accept uncertainty, which is nearly everything, quietly.” In the essays that he published over more than three decades, he turned even his equivocations into dictums as he explored subjects that included not only art, architecture, and the art world, but also urban development and national affairs.

What rescues even Judd’s most sweeping pronouncements from crackpot irascibility is the easy, pungent power of his prose. He arranges relatively simple nouns and verbs (and a minimum of adjectives) in sentences and paragraphs that have a plainspoken, workmanlike beauty. Judd’s direct, unequivocal writings are a perfect match for his sculptures, with their precisely calculated angles and unabashed celebration of industrial materials such as plywood, aluminum, and Plexiglas. This fiercely independent artist belongs in a long line of American aesthetes who embraced an unadorned style, including figures as various as Ernest Hemingway, Barnett Newman, Virgil Thomson, and Walker Evans.

Reading Judd’s prose two decades after his death, you will experience, amid the overheated and gaseous atmosphere of the contemporary art world, an invigorating blast of cold, clear air. Donald Judd Writings, although not the first collection of his prose, is the first to span his entire career. Edited by Flavin Judd, the artist’s son, and Caitlin Murray, the book includes, in addition to previously published work, selections from notes that Judd made over the years. All the way through, you hear the voice of a man who was never afraid to say no. It was not the refusal of an outsider, however, at least not in his earlier years of writing and exhibiting. Judd’s no is that of the dedicated avant-gardist—the man who leads the charge. This no is fundamentally positive and celebratory—a cry for the new.

Judd believed that the search for the new involved, both in his own work and the work of his contemporaries, a rejection of the conventions of painting and sculpture in favor of new forms, which were often aggressively curious or idiosyncratic and startlingly sized or scaled. Judd refused to favor either representational or abstract images. He was an enthusiast for Claes Oldenburg’s oversized quotidian objects, Lee Bontecou’s shaped canvas convexities, Lucas Samaras’s bedecked and bejeweled boxes, and Dan Flavin’s fluorescent geometries. He gathered these variegated works by his contemporaries under a singular rubric when he titled one of his most famous essays “Specific Objects” (1964).

Although Judd had a great deal to say about many varieties of art, architecture, and design, he was a man with one big idea. “Most works finally have one quality,” he wrote in “Specific Objects.” “The thing as a whole, its quality as a whole, is what is interesting.” In Judd’s grandest sculptures he certainly proved his point. I’m thinking especially of the hundred aluminum boxes gathered together in two buildings in Marfa, Texas, and the richly polychromed wall-hanging compositions of his later years.

While everybody who cares about the arts will agree that unity and complexity are both qualities to be admired, there is a fundamental divide between those who crave a complexity that may risk disunity and those who crave a unity that may give short shrift to complexity. Judd, although his heart was always with unity, knew that it was enriched by variety. His hundred aluminum boxes, although alike in their external dimensions, are subdivided inside in many different ways. His polychromed wall-hanging compositions dazzle with their playful, unpredictable color orchestrations.

In an essay entitled “Symmetry” (1985), Judd declared that “art, for myself, and architecture, for everyone, should always be symmetrical except for a good reason.” But he immediately went on to observe that “symmetry itself allows variation,” and that there are forms of symmetry that are “very close to asymmetry.” There are intricacies amid Judd’s simplicities. That’s what gives both his sculpture and his writing their staying power.

Judd grew up in New Jersey, served in Korea in 1946–1947, and attended the Art Students League and Columbia University, where he studied philosophy and graduated cum laude in 1953. The first three essays in Donald Judd Writings, previously unpublished, were written while he was doing graduate work in art history at Columbia later in the 1950s. They reveal a mind and a style almost fully formed. In these essays about a Peruvian wood carving, a marble relief by the seventeenth-century French sculptor Pierre Puget, and an Abstract Expressionist painting by the New York artist James Brooks, there is already the methodical attentiveness and the razor-sharp analysis.

Advertisement

Judd abhors a mystery. He demands clarity. In describing an impossibly crowded Baroque battle scene, he cuts straight through the pileup of human beings in various states of stress, arguing that the painting is “organized through a virtual grid of diagonals of varying directions and prominence.” Judd took at least one course with the great art historian Meyer Schapiro at Columbia, which leads me to wonder if he was somehow influenced by Schapiro’s bold but methodical mind—by his combination of boundless curiosity, strenuous critique, and analytical precision.

“I leapt into the world an empiricist,” Judd wrote in 1981 in an essay about the Russian avant-garde. In the graduate school essay about James Brooks, he quoted David Hume’s ideas about “the nature of substance,” and commented that “much present American painting seems related to the indigenous pragmatic philosophy, especially Peirce, and its source, the similar British Empiricists.” Judd began with an empiricist’s taste for the concrete, the particular, and the specific. That taste never left him. He wanted to nail things down. He began his long discussion of Brooks’s lyrical abstraction with a simple declaration: “In the contemporary dichotomy of the dispersion or concentration of form, Brooks’s work is mediate.” In the next few sentences, he assigned particular places within this contemporary dichotomy not only to Brooks but also to Jackson Pollock, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and a Frenchman, Pierre Soulages. Judd, still a student, was very much in control—a young, masterful mind, sizing up the situation.

Beginning in the late 1950s, when many writers were still inclined to cast what was being referred to as the new American painting of Pollock, de Kooning, and Rothko in a romantic light, Judd argued that these artists weren’t dreamers and mythologizers but realists and pragmatists, albeit of an altogether different kind. Writing about Pollock in 1967, he complained that most discussions of Pollock were “loose and unreasonable.” No doubt thinking of the writers who had associated Pollock’s mazelike dripped canvases with mystical cosmologies or the hurly-burly of urban life, Judd observed that “almost any kind of statement can be derived from the work: philosophical, psychological, sociological, political.” He wanted to distinguish Pollock’s paintings from the expressionism of Soutine and van Gogh, which he saw as “portray[ing] immediate emotions.” This, so he explained, “occurs through a sequence of observing, feeling, and recording.” Pollock, Judd believed, wasn’t concerned with emotions but with “sensations.” Emotions were evolutionary; sensations were immediate. “The dripped paint in most of Pollock’s paintings is dripped paint,” he wrote. “It’s that sensation, completely immediate and specific, and nothing modifies it.”

For Judd writing became a way of reasoning his way through the world—of reconciling the singularity of his own artistic vision with the chaotic heterogeneity of the art and ideas that he encountered everywhere he turned. When he first collected his writings in 1975, he claimed that much if not most of what he had written between 1959 and 1965 for Arts magazine he had written “as a mercenary and would never have written…otherwise.” Writing had been little more than a way to eke out a living. “Since there were no set hours and since I could work at home it was a good part-time job.” I don’t think this can be taken at face value. While Judd was surely frustrated by having to write short reviews of the work of artists who interested him little if at all, there was a wonderful steadiness about his eye and his mind as he chronicled the sea changes that were overtaking the New York art world in the early 1960s. It was a tumultuous time, with contemporary art acquiring a growing prestige even as many artists and writers worried that the old modern ideas and ideals that had nourished the Abstract Expressionists were proving unworkable and perhaps totally irrelevant. Judd was eager to sort it all out and find a way forward.

Critical essays and reviews resurrected decades after they were first written can convey the atmosphere of a time, but they can also feel dim and obscure—the stakes once so high now registering as little more than stale skirmishes, with yesterday’s battle lines all but erased. I can understand readers dismissing as hardly more than ill-tempered backbiting and gossip Judd’s characterization of Clement Greenberg’s views as “little league fascism” or Michael Fried’s opinions as “pedantic pseudo-philosophical analysis.” But if Judd’s rhetoric sometimes reached a fever pitch, it was not without reason. A great deal was at stake as the authority of the Abstract Expressionists waned. Judd was one of a number of artists who felt the need to speak out and found themselves doubling as eloquent critics. In Art News and The Nation, the painter Fairfield Porter looked toward a revival of representational painting that might build on the strengths of de Kooning’s painterly abstraction. And writing alongside Judd in Arts, Sidney Tillim, although a painter little known today, vigorously articulated the sense shared by many that Abstract Expressionism had mostly degenerated into mannerism and affectation.

Advertisement

For all that Judd believed in the unity, wholeness, and singularity of works of art, he was equally convinced that the conditions that invited creation were variable, diverse, and unpredictable. In both “Specific Objects” and another essay written in 1964, “Local History,” Judd rejected any unified theory of the history of art. This was the heart of his disagreement with Greenberg—as well as with Fried, who even as he was extending and transforming Greenberg’s ideas launched a direct assault on Judd in his essay “Art and Objecthood.” Judd sensed an underlying and unwanted Hegelian idealism in Greenberg’s belief that any authentic artistic style, as Greenberg put it, “had its own inherent laws of development.” “The history of art and art’s condition at any time,” Judd wrote in 1964, “are pretty messy. They should stay that way.”

Judd disliked the simplification implicit in a stylistic label such as Abstract Expressionism. Indeed, he rejected the labels that were ascribed to his own work and that of close friends, such as Minimalism and ABC Art. “‘Crisis,’ ‘revolutionary,’ and the like,” he observed, “were similar attempts to simplify the situation, but through its historical location instead of its nature.” Judd, whatever the unified look of his own work, applauded the pluralism of the early 1960s. He saw a situation in which “a lot of new artists” had “developed their work as simply their own work. There were almost no groups and there were no movements.” He believed not in world history but in what he called local history.

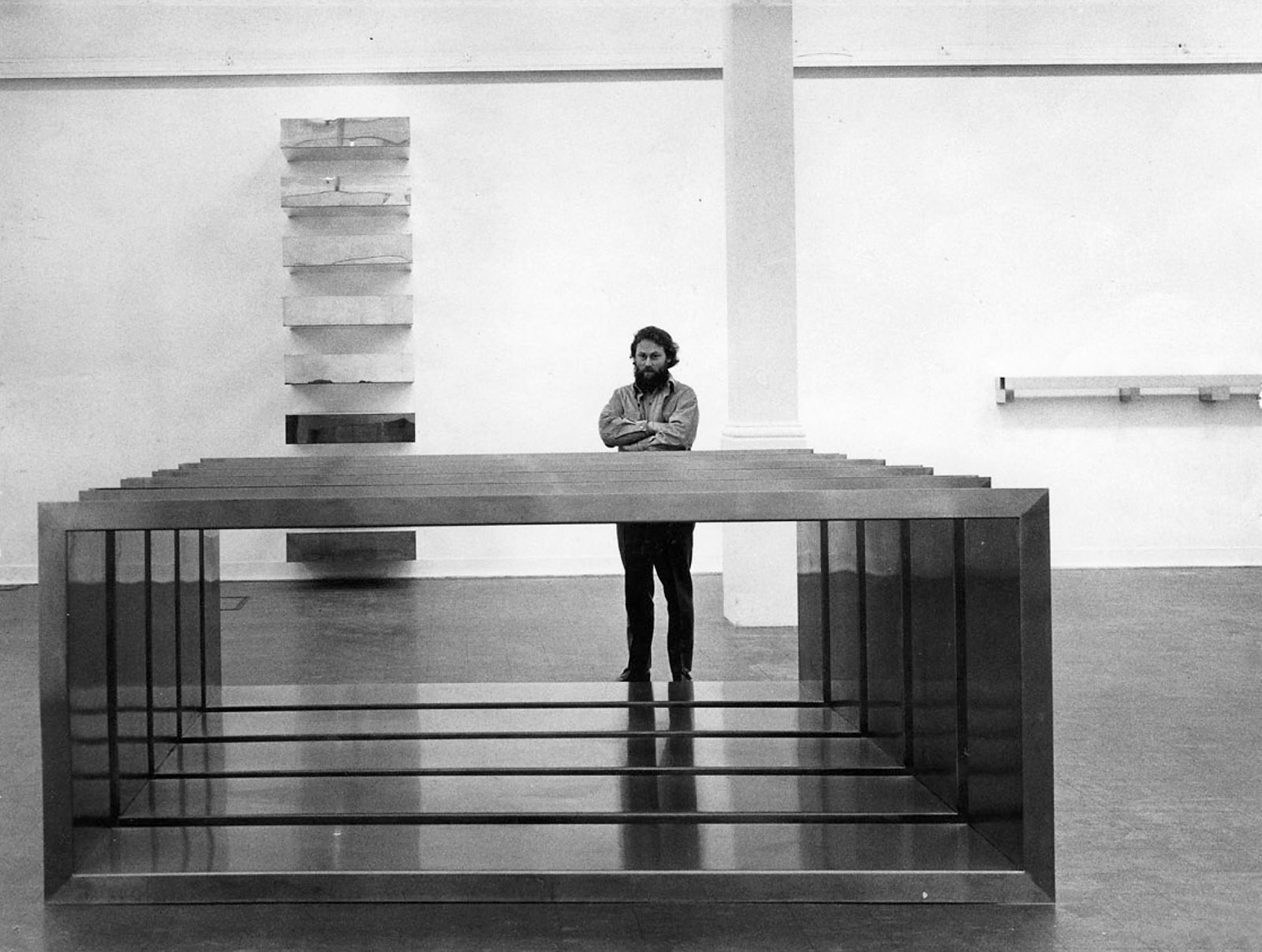

Judd had his first one-man show at the Green Gallery in New York in 1963, at a time when he was as active as a critic as he would ever be. He exhibited a number of works that hung on the wall and behaved rather like paintings, even as their curved and convex edges, insistently symmetrical compositions, and elements of galvanized iron and aluminum put gallerygoers on notice that they were dealing not with metaphors but with actualities. Perhaps even more arresting were a few works that Judd set on the floor. With their blunt, carpentered wooden shapes, they suggested enigmatic inventions not yet under copyright. The most striking was a right angle made of two pieces of wood painted cadmium red, with a black pipe fitted between them and also right-angled, so as to create a pokerfaced juxtaposition of right-angled red wood and right-angled black pipe.

The inscrutability of Judd’s work, which some might be tempted to describe as a Platonic cool, could more accurately be described as an impassioned particularity. The key to it is to be found in the distinction between emotions and sensations that Judd made when he wrote about Pollock. From the very first, he wanted to present gallerygoers with surprising sensations. In the early work exhibited at the Green Gallery, it was sensations of rectilinearity, right-angledness, curvedness, and redness. Judd turned his back on narrative or storytelling, which abstract artists from Kandinsky and Brancusi to de Kooning and David Smith had not so much jettisoned as reimagined in nonnaturalistic ways. Judd hungered for something sharp, clear, and immediate. He was for being, not becoming.

In 1989, looking back to the idealism of the early twentieth century, Judd remarked that “Mondrian tried to keep the larger view in mind, while I, we, are not sure that there is a larger view.” That “we” is striking—a declaration of a communal sense of diminishment. For all the aloof, mandarin elegance of his art, Judd was in many respects a characteristic figure of the later 1960s and early 1970s, when the initial hopes of the Civil Rights movement and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society had given way to despair following the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Robert Kennedy, the traumas of the inner cities, the struggles of the antiwar movement, and the ever-growing radicalization of the left. Judd’s work was fueled by a determination to create something extraordinarily lucid in a world where confusion reigned. He had no choice but to embrace the particular and enlarge it—ennoble it. Like so many men and women of his generation, he believed in beginning again, rethinking every aspect of human experience. There is something in Judd’s self-reliant, can-do attitude that brings to mind the sensibility of the Whole Earth Catalog, which was first published in 1968. Judd’s imagination, in which an instinctive skepticism is shot through with flashes of hope, makes him an exemplary artistic figure to contemplate in considering those troubled times.

In the first flush of fame, when some New York real estate was still relatively affordable, Judd bought a cast-iron building at 101 Spring Street. The year was 1968, decades before SoHo became the shopping mall it is today. Judd was one among a group of artists who were determined to preserve the old industrial neighborhoods of downtown New York and revitalize them as artists’ neighborhoods. Here was local history in action. “Everything that can be stopped, started, run by a community should be run by that community,” he wrote in 1971. “The decision to delegate something to a wider area, say the city or the county, should be very carefully made.” Judd had an almost utopian vision of human society; he wanted to get back to basics.

The building he bought was a beautiful, simple structure, five stories high, on the corner of Spring and Mercer Streets, with the cast-iron grid of the façade framing expansive planes of glass. Twenty years later, he wrote lovingly about this structure, designed by Nicholas Whyte, “whose only other cast-iron building is in Brazil.” He noted the ruinous state of the interior when he bought it, and how he carefully restored it. He characterized the building as “a right angle of glass. The façade is the most shallow perhaps of any in the area and so is the furthest forerunner of the curtain wall.”

He described it as if it were one of his own sculptures. “The given circumstances were very simple: the floors must be open; the right angle of windows on each floor must not be interrupted; and any changes must be compatible.” In this building, which Judd speculated had been used for the manufacture and sale of some sort of cloth, he found an aesthetic that somehow prefigured his own. He argued for this not as some grand historical continuum but as a particular affinity—an artist of the later twentieth century sensing some connection with an architect of a century earlier.

“Finally,” Judd wrote in 1988, “the only ground you have is the ground you stand on.” It was that search for something steady—some foundation on which to build and live—that inspired not only Judd’s fascination with downtown New York but also his increasing involvement with the life and landscape of the American Southwest. He was already becoming interested in cacti and Native American ceramics and rugs in the early 1970s, when he began looking for a place where he might spend time and work and perhaps display some of his larger compositions along with some by his friends. He found his way to Marfa, Texas, a town south of El Paso, near the Mexican border. In an essay about Marfa that he wrote in 1985, Judd brought a laconic passion to his description of the land. “The area of West Texas was fine, mostly high rangeland dropping to desert along the river, with mountains over the edge in every direction. There were few people and the land was undamaged.” For Judd, this measured, steady description was high praise indeed.

Ever entrepreneurial when it came to finding a way forward with his work, Judd soon enough bought a number of buildings in the practically abandoned town of Marfa and then took over an old army base, which he turned into the Chinati Foundation. Much of the writing of his later years—whether done in Texas, New York, or Switzerland, where he also spent time—concerns his evolving vision of places to work, exhibit art, and live. He became interested in designing furniture and architecture and wrote about the differences between functional and nonfunctional objects, often looking back with a critical eye to the experiments of the Bauhaus and the De Stijl movement in Europe. He sounded off about the state of contemporary architecture, praising Louis Kahn and raging against the postmodernism that Philip Johnson was advocating for at the time. Johnson became a bête noire. Even his Miesian Glass House, almost universally admired, came in for criticism; Judd called it “discreetly vulgar.”

Some of the most interesting of Judd’s later writings are about artists whom he admired and whose work he eventually exhibited at the Chinati Foundation. He wrote about artists of his generation and devoted a long essay to an enormous horseshoe, Monument to the Last Horse, by Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, which was set up at Chinati in the 1990s. His taste remained unpredictable. He took a great interest in a Swiss geometric painter, Richard Paul Lohse, who has remained relatively unknown in the United States. And at a time when Josef Albers had come to be seen by many as a somewhat outdated figure, Judd embraced his work with considerable vigor.

The closing essay in the new collection, “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular” (1993), is a magnificent piece of writing in which Judd reaches far and wide as he explains the thinking behind his own opulently colored late wall-hanging works. He explains: “The last real picture of real objects in a real world was painted by Courbet.” The real, the immediate, is always what he’s after. “Color is like material,” he writes at one point. “It is one way or another, but it obdurately exists. Its existence as it is is the main fact and not what it might mean, which may be nothing.” Here we see the core of Judd’s vision, a purity that’s precisely not Platonic, that’s anti-ideal—a purity of the real. Thinking about Mondrian, Malevich, and Van Doesburg, he finds himself wondering why “it is idealistic—even what does that mean—to want to do something new and beneficial, practical also, in a new civilization.” Judd wanted to liberate the search for the new from the search for some ideal.

The new volume, beautifully designed, would have certainly pleased Donald Judd. There are more than eight hundred pages of text and more than a hundred of illustrations, contained in a format so compact and well constructed that it can easily be held in the hand. The bright orange canvas covers are strong but flexible. And the orange is beautifully set off by the cerulean blue endpapers, for an effect that has some of the drama of Judd’s own late polychrome works. The pages of his private notes, often quite brief, are a welcome addition to the writings we already know. They offer a different kind of reading experience—quick, glancing, sometimes witty. Judd can illuminate an entire era in a few sentences. This is what he has to say about Bernini, that commanding figure of the Roman Baroque: “Bernini made religion, supposedly the nature of the world, personal. And so religious art and architecture ended; after that it was sentimental and academic.” Judd is suggesting that a genius can, all at once, brilliantly transform and catastrophically terminate a tradition.

I wish this new collection included some of the short reviews that Judd published in Arts in the early 1960s, because they reflect the reach of his imagination. Although they are part of the Complete Writings 1959–1975—which is now back in print—they would have helped give a fuller picture of Judd’s thinking in what is bound to become the essential collection of his prose. Those short reviews are certainly of more significance than the seventy-page critique of the collector Giuseppe Panza included here, in which Judd lays out an altogether credible indictment of this Italian who took it upon himself to make unauthorized versions of some of his work. Judd in high dudgeon is fun to read, but his vehemence is most exciting when grounded in deep thought. When he entitled a two-part essay “Complaints,” he knew that he could get away with that almost self-mocking title because he was a person who didn’t just complain. There was substance to his gripes. He was spot on when he complained about the banality with which his art and the art of his friends was exhibited in most galleries and museums. The eloquent installations of his own work in Marfa prove that he knew of what he spoke. Judd was a visionary—a visionary of the real.

Reading Judd, I am reminded of the prophetic voices of certain nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century artists and writers—of Gauguin, Kandinsky, Pound, and Lawrence. Whatever Judd’s skepticism about the idealism of early-twentieth-century abstraction, he admired the great modern visionaries, especially Malevich and Mondrian, and he brought some of the quickening power of their manifestos into his own writing. Prophetic figures who castigate the societies that formed them are almost inevitably paradoxical figures. Judd was certainly aware that a prophet can set off complex, even masochistic reactions in his contemporaries, who embrace (or at least half embrace) his criticisms as a way of expiating what they may be inclined to regard as their own sins. What is perhaps Judd’s most famous diatribe, the two-part “A Long Discussion Not About Master-Pieces but Why There Are So Few of Them,” originally published in Art in America in 1983 and 1984, can still send a shiver of excitement and confusion down the spines of people who first read it more than thirty years ago. No wonder Judd had an ambivalent relationship with so many critics, curators, and collectors. Even as he gleefully pointed out their mistakes, they lionized him and made him a wealthy man.

Judd began his “Long Discussion” with a line from Gertrude Stein: “Everything is against them.” Judd was emboldened by a battle. But in his art, his writing, and his life, he was never anything less than a man of affirmations. He affirmed the astonishing beauty of what some might dismiss as ordinary things: a box carpentered of plywood; an aluminum construction painted in shades of red, yellow, blue, orange, and black; a simple declarative sentence. He reminds us that the ordinary can be extraordinary. If a man can be a pragmatic utopian, that man is Donald Judd.

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

The Adults in the Room

Dialogue With God