How insular a community is may be measured by its share of members who wish to appear on camera. When a casting call went out to New York’s ultra-Orthodox community, which numbers in the hundreds of thousands, to appear in Menashe, a feature film set in the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, only sixty people showed up. “I would call it un-casting,” Joshua Z. Weinstein, the film’s director, told an interviewer. Even after they agreed to participate in the film, many of the actors soon dropped out, citing rabbinical prohibitions or cold feet. A full cast list has yet to be released; the filmmakers are worried that even extras could face excommunication.

Menashe’s clandestine aspect—it was shot in secret entirely within the Hasidic community it depicts—has at least one salutary side effect: it lends the story an understated, naturalistic quality that might have been missing in a flashier production. That quality is heightened by the fact that most of its cast members are first-time actors, and many had never stepped inside a movie theater. Menashe is spoken completely in Yiddish, except for one brief but consequential scene in English (to which I’ll return). It loosely tells the real-life story of Menashe Lustig, the ultra-Orthodox actor playing the title character. Having been widowed for a year, Menashe wants to raise his ten-year-old son, Rieven, by himself. But his religious faith won’t allow it. As the Book of Genesis says: “It is not good that the man should be alone.” Until Menashe remarries, a rabbi decrees, Rieven is to be left in the custody of his uncle and aunt. But Menashe doesn’t wish to remarry, and the rabbi gives him a week to prove himself as a single father.

The plot takes place during that week, as Menashe, a devoted father but a helpless klutz, bumbles his way through his parental duties and his low-paying job behind the cash register of an ultra-Orthodox-owned supermarket. He is always short on money and on the verge of being fired. He gets drunk on a night out with his son, oversleeps, then gives Rieven Coke and cake for breakfast. Our desire to see Menashe win custody of Rieven is complicated by the fact that he is far from an ideal father. When Menashe’s stringent brother-in-law blames him for having neglected his wife when she fell ill, Menashe doesn’t dispute him.

Still, we find ourselves rooting for Menashe. It helps that Lustig is a born actor, with a rare ability to project comic expressiveness at key dramatic moments. One of the film’s most riveting scenes is without dialogue: we simply watch as Menashe moves about his cramped apartment, knocking over a plastic cup here, scratching his belly there. His physicality is thoroughly commanding—like a paunchy Chaplin with a yarmulke. So embedded are we within the strictures of Orthodox life that even when Menashe slaps Rieven for a small infraction, we quickly forgive him. When Rieven asks his father, who wears a black yarmulke and whose tzitzit, or prayer shawl fringes, dangle out from under his shirt like curtain tassels on a windy day, “Why don’t you wear a hat and coat like everyone else? You’d look much nicer,” I found myself thinking: Yeah, Menashe, why don’t you?

The lifelike feel of Menashe is further compounded by improvisation. Weinstein has said that because of his casting problems, the film’s script had to go through countless iterations. A large part reserved for Menashe’s father-in-law, for example, had to be scrapped: the actor playing the role pulled out after shooting began. Then there was the language barrier. Yiddish is the main language spoken by most ultra-Orthodox Hasidim (but not by Chabadniks or Lithuanian Orthodox Jews, who converse in Hebrew). Yet neither Weinstein nor his fellow writers speak it. So the actors were given free rein to translate the English script as they saw fit. The resulting dialogue comes across as refreshingly unpolished—the English subtitles rightly read like a translation, not like a superior original. The same unpolished veneer characterizes the film’s visuals. At one point, Menashe and Rieven look for decorations to liven up the bare walls of their apartment. Most pictures are out of the question. Instead, they settle on a watercolor portrait of a rabbi, set against a pinkish sunset. “Very authentic,” Menashe says approvingly.

For a film that focuses on parent-child relations in the wake of a tragic death, Menashe remarkably eschews sentimentality or lazy conjecture. You may, for example, presume, as I did, that Menashe does not wish to remarry because he is still in love with his late wife. You’d be wrong. Their marriage, we find out, was not a happy one. The couple met through a matchmaker on a mutual trip to Israel, and spent most of their time together fighting. Even a moment of tenderness, in which Menashe gives his son a fluffy little chick, isn’t saccharine. As Rieven pets it, his father belts out a song in Yiddish: “Tomorrow we’ll have you in the chicken soup.” Both father and son laugh. Menashe thus follows the very best of Yiddish literary tradition—Sholem Yankev Abramovitsch (known by his alter ego Mendele the Book Peddler) comes to mind, as does Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich (Sholem Aleichem)—in which gallows humor is the surest salvation from kitsch.

Advertisement

Menashe’s depiction of Hasidic society is likewise nuanced. Weinstein, whose background is in documentary, is interested in life as it is, not in life as it should be. (Nor is he interested in bogging down his story with explication: we watch Menashe and his neighbors feed a growing conflagration with no commentary on its being Lag BaOmer, a holiday celebrated by lighting bonfires.) Despite Menashe’s small rebellions—his informal attire, his refusal to remarry—there is no question of his leaving the confines of his religion, no matter how unfair its rabbinical edicts. Whether or not Menashe gets to raise his son, the film makes clear, he will remain within the rigid boundaries of Borough Park—home to one of the largest Hasidic communities outside Israel.

Hasidism, a spiritual movement that grew out of ultra-Orthodox Judaism in the eighteenth century, is comprised of different sects, each with its own tzadik, or “righteous” leader. The majority of Borough Park residents are Bobover Hasidim who originated in Galicia, in today’s southern Poland. The Bobovers are credited with establishing a major ultra-Orthodox community in the United States after a near-complete annihilation of their sect in the Holocaust. Much like the Satmars of Williamsburg, they belong to a zealous, antimodernist branch of ultra-Orthodox Judaism, though one that is less vocal against the State of Israel than the Satmars. Lustig himself is a member of a far smaller sect, called Skver, that is based in New Square, a village in Rockland County, New York, where men and women walk on separate sides of the street.

Women often occupy a paradoxical position in Hasidic life—a position Menashe deftly portrays. They are largely absent from civic life, yet hold much power when it comes to the home. In some Hasidic circles, they are even employed in fields that are considered too modern for men, such as computer work or design. This is particularly true in Israel, where Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, women serve as their households’ main breadwinners while more than half of Haredi men don’t work and spend their days studying the Talmud. An old Jewish joke tells of a devout woman who says that her husband is in charge of the “big things,” such as going to war or relations with the king, while she is responsible for the “little things”: their livelihood, their children’s education.

This ambivalent status of ultra-Orthodox women—outsized yet marginalized—can be summed up in one sentence that Menashe utters matter-of-factly partway through the film. Why marry, he asks his rabbi, if a stepmother wouldn’t be allowed to touch his son anyway? In other words, a woman’s presence is so vaunted that a man cannot be expected to raise a child without her, but she is also deemed ritually impure and cannot touch even a young boy who is not her blood relative. Such is the plight of ultra-Orthodox women.

Unsurprisingly, the dialogue in the film is spoken almost exclusively by men. A rare exception is a scene in which Menashe goes on a blind date organized by a community matchmaker. The meeting is cold, like the ice cubes in the couple’s Coke glasses. As befits Orthodox custom, they barely make eye contact. “Besides marriage and children, what else is there?” Menashe’s date asks him solemnly. Menashe sighs. Oy.

Not only are women otherwise largely missing from the film, but so is secular life. Unlike the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, which is famous for its outreach, the majority of ultra-Orthodox Jews shun non-Hasidic society. Only once do we see Menashe interact with anyone outside his community, and to hear him suddenly speak in English (a halting English, at that) is so jarring that we forget this has been New York all along. He is seen sitting with two Hispanic employees of the supermarket after a long day’s work. All three are sipping beer from forty-ounce bottles as the men invite Menashe to join them on a night out. Menashe laughs. With them he feels welcome, at ease. And yet part of the joke is precisely the impossibility of their proposition: Menashe will not be joining their fiesta, of course. Though he may find his religion suffocating, its pull is too strong for him to resist.

Advertisement

Menashe ends exactly as it begins, with a long shot of Menashe pacing the streets of Borough Park, drowned out by a sea of other people—with one difference. He now wears a long coat and black hat. Not only will he not be rebelling against his community but he seems to have taken to heart their criticism of him and to be eager to do better. It may not be the lesson we were hoping for, but this, after all, is life.

Another portrayal of the pressures on young religious people to marry can be found in Srugim, an Israeli drama series that premiered a decade ago and streams with English subtitles on Amazon. Though decidedly less insular than the ultra-Orthodox of Borough Park, Israel’s national-religious movement, known outside of Israel as Modern Orthodox, still tends to view secular television and cinema with a combination of skepticism and distrust.

Srugim was written by two religious filmmakers, and deals with the dating lives of single religious Jerusalemites: Yifat, a genial graphic designer; Hodaya, a rabbi’s daughter who undergoes a crisis of faith; Nati, a heartthrob doctor; Amir, a divorced Hebrew teacher; and Reut, a no-nonsense accountant. In an early episode, Yifat and Hodaya, who have been best friends since their days in Bnei Akiva, a religious youth movement, are squinting in front of a computer, bemoaning the fact that nearly all religious parts on Israeli commercials and TV are performed by nonreligious actors.

Hodaya: “That religious kid smiling next to the Coke bottle?”

Yifat: “I don’t think an Orthodox family would allow its son to shoot a commercial for Coca Cola.”

Hodaya: “The ultra-Orthodox guy from Visa?”

Yifat: “I think he’s Swedish.”

Hodaya: “Why is it? Don’t we deserve models from the sector?”

The irony, as Israelis will pick up on, is that the two well-known actresses offering this bit of dialogue—Yael Sharoni and Tali Sharon—are themselves nonreligious, as are the other actors. And yet when it came out, Srugim proved a hit among religious Israelis—as well as a hit generally: the newspaper Yediot Ahronot called it “a rare instance of superb television.” While Menashe will not be watched by the very community it portrays, Srugim is a more mainstream affair. In a way, Srugim can be seen as the reverse of Menashe: written by “insiders,” cast with “outsiders,” and watched by both insiders and outsiders alike.

Srugim means “knitted” and is short in Hebrew for kippot srugot, or “knitted yarmulkes,” the ones worn by Israel’s national-religious Jews. To say of a group of people that they are srugim conjures in Israel a specific segment of society: people who take an active part in all of the country’s institutions (military, parliament, universities) while also adhering to the strict interpretation of Jewish law. They keep the commandments; they observe the Shabbat; they do not touch members of the opposite sex before marriage.

Active participation in political and civic life has been the main distinction between the Zionist religious Jews and the Haredim—the ultra-Orthodox—since the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, an event that tore religious Jews apart. Leaders of the ultra-Orthodox community rejected the nascent country as an “attempt to replace divine agency with human agency,” in the words of Moshe Halbertal, a scholar of Jewish philosophy, whereas national-religious Jews came to regard Israel’s founding with rapture—as a hastening of redemption and of the arrival of the Messiah. If secular Israelis defined the country’s early decades (David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, the kibbutznik pioneers), the Zionist religious Jews are likely to define its future. Their ranks, due to very high birthrates, are swelling: about a quarter of Israelis identify as national-religious, according to 2014 statistics from the Israel Democracy Institute. Interestingly, only 10 percent of Israelis described themselves as religious when asked solely about religiosity without adding nationalism to the mix, suggesting that the definition is fluid and that Zionism plays an important role in their self-perception.

Srugim has been described, not outlandishly, as the Israeli Friends (though it’s not a sitcom). Most of its scenes take place inside an apartment in the Old Katamon neighborhood of Jerusalem, and the focus never veers from the group of five singles at its center. But because this is Israel, politics are never far away, either. Yifat attempts to clear her head and escape city life by moving to a West Bank settlement—a move that is presented as rational and commonplace. In a 2008 interview with a religious Israeli publication, Laizy Shapiro, the co-creator of the show, who lives on a settlement himself, took pride in having bussed the entire production team “across the Green line” for the shoot, calling it a “great accomplishment.” Only twice, and briefly, do we see Arabs mentioned on the show: once when Nati gets rid of a nonkosher sandwich by handing it to an Arab doctor, who quips, “I hope it’s not poisonous.” Another time, Yifat and Amir think they see an Arab man and run away in fear, only to discover that the man was, in fact, a neighbor’s relative.

If all this sounds riling to a liberal sensibility, Srugim was also met with criticism from ultra-religious groups in Israel who argued that the series had “crossed many red lines,” as one review on Arutz Sheva, a news site identified with the religious right, put it. The show’s transgression? “Saying prayers in vain, having a woman bless the wine in front of men, and, above all, breaking many of the modesty precepts between men and women, from touching to more blatant acts.” That the series should be rebuked by religious Jews for not being modest enough is unsurprising. What is surprising is the opposite: that its creators managed to bring to Israeli prime time a show about dating where the most “blatant acts” include nothing more than a rare kiss or a daydream of jumping on a bed with one’s love (on a bed, not into bed), and one scene in which sex is portrayed only by showing a married couple in bed, fully covered, after the fact.

If anything, Srugim makes a rather convincing case for religious Judaism, with an emphasis on family and on a tight-knit sense of community. By contrast, the picture that emerges of secular life revolves around lighthearted bromides about food. Secular people, we are told, eat fancy cheese and “fly off to Barcelona to eat squid” and complain about store-bought cake. On the one hand, Hodaya’s growing disillusion with religion is presented sympathetically—in one of the show’s most affecting scenes, she has an exchange with a formerly religious writer who tells her: “All the laws and the commandments and the fact that everyone knows what to do all the time, I felt like that’s the furthest thing from God.” On the other hand, there is a nagging implication in the series that secularism equals selfishness. As Hodaya questions her faith, she repeatedly turns down job offers and romantic partners, deeming them all beneath her. “Stop looking down on everything,” Yifat berates her at one point. “Stop thinking that you’re so special.”

I confess that I may be bristling at the show’s depiction of nonreligious life more than is warranted. To be fair, one of the most endearing characters is Avri, a secular Ph.D. with whom Hodaya falls in love. But since I grew up in a secular family in Jerusalem only a few blocks from where the series takes place, watching Srugim felt strangely personal to me, like a home video beamed out to the world. The series namechecks little havens of nonreligious life that my friends and I used to frequent: Smadar cinema, Café BaGina, Emek Refaim Street in the German Colony.

But such places are disappearing at a dizzying pace (or else turning glatt kosher). Today, 35 percent of Jerusalem residents define themselves as Haredi while only 21 percent say they are secular—an increase of 5 percent and a decrease of 7 percent respectively compared to a decade ago, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics. This in itself would not be an issue were it not for the growing realization that secular people are increasingly unwelcome in the city: the process of Jerusalem’s “Haredization” peaked a few years ago when all images of women were scrubbed from the city’s billboards. It’s no coincidence, perhaps, that when Hodaya and Avri affirm their love, they’re on the beach in Tel Aviv.

Srugim at times feels contrived, heavy-handed. More than once it suffers from what I’ve come to think of as a tendency in Israeli productions to cram in “and, and”—in this case, to deal with divorce and homosexuality and infertility and losing one’s faith, sometimes in a single episode. I suspect this has to do with the richness of Israeli society and the attempt by Israeli writers to encompass it all, to check every box on its multitude of layers. All the more so in recent years, when so much of Israeli television is being made with an eye overseas, where a larger audience and big money beckon. (Such productions have a proven track record: Homeland originated in Israel, as did HBO’s In Treatment; the thriller Fauda, about a special forces unit of the Israeli military, is available on Netflix; the excellent drama Shtisel, about a Haredi family, is currently being adapted by Amazon.)

But it’s not often that a TV show centered on romantic entanglements—that most hackneyed of tropes—comes across as bracing. “There’s no place for single life in the religious community,” Shapiro said when the show’s first season aired in Israel. “If you don’t have a family or a wife, you barely have an existence in religious society.” Dating, for the characters of Srugim, isn’t casual or diversionary: it is existential. A sense of high drama drives their encounters—chaste as they are—emphasizing just how high the stakes are. No milestone is dreaded on the show quite like turning thirty alone. And so the characters date aggressively: speed dating, online, through acquaintances, even at synagogue. (“You pray at Yakar, but all the girls are waiting at Ohel Nehama,” Yifat tells Nati). They are desperate to start a family, but are not willing to give up on love in the process, or on professional fulfillment. When Reut realizes that her boyfriend resents her earning more than him, she promptly breaks up with him. And that, in the end, may be the show’s quietly radical stance—one that is also echoed in Menashe. Love and marriage, yes. But at what cost?

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

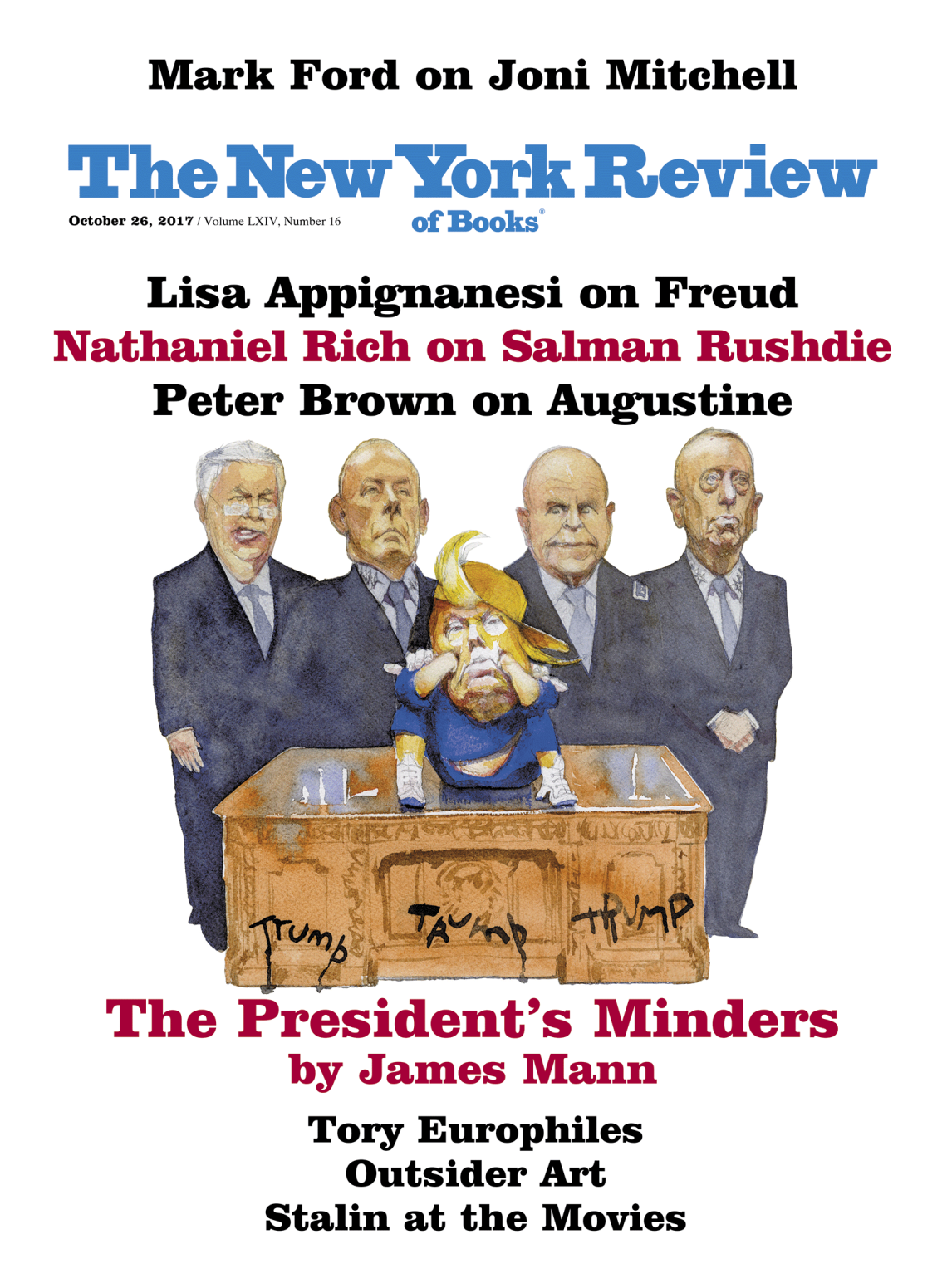

The Adults in the Room

Dialogue With God