The tousled strands of a deep pile rug give a painter a pleasant rhythm to mimic. Curling every which way in little wavelets from the confines of the carpet backing, they offer an orderly disorder for the brush to reinvent. There are three particularly inviting rugs among the 135 works—from paintings and drawings to photographic composites and multiscreen installations—assembled in the retrospective of David Hockney’s work now at the Metropolitan Museum. One of them snuggles around the bare feet of a fashion designer friend of Hockney’s in Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, a ten-foot-wide canvas from 1970–1971 that has lodged in the British imagination as an icon of a modern London at ease with itself, its heritage suavely renovated. A swish young couple pose, cocksure yet winsome, in a Victorian piano nobile that they have decluttered: little interrupts its pastel expanses but a white telephone, a vase of white lilies on a white modern table, Percy the white cat, and the off-whites of the shag pile into which those toes are sinking in woolen warmth—a single sensuous incident singing out from the cool, impeccable acrylic rendering.

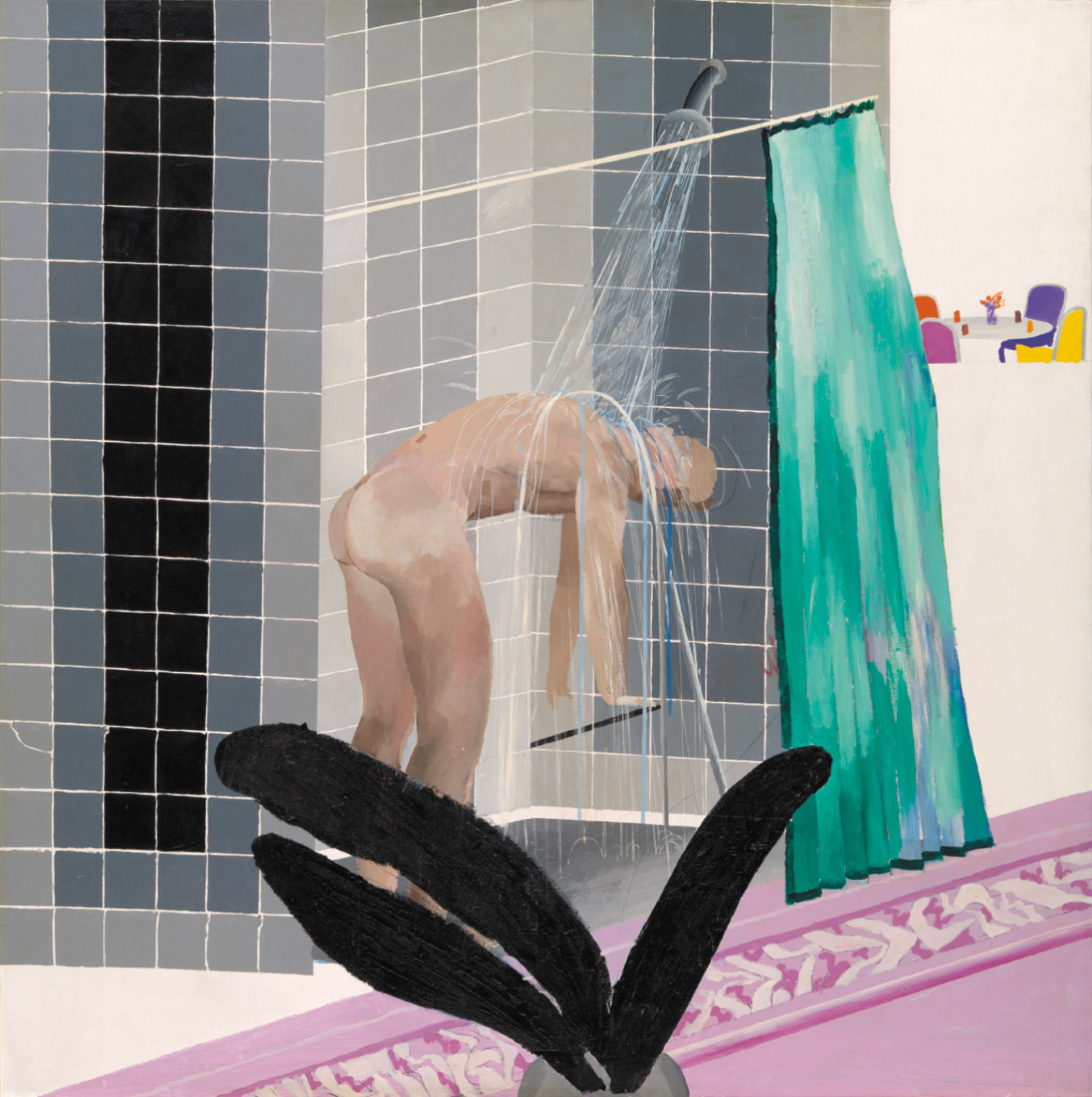

Figure and floor don’t meet in The Room, Tarzana, which was painted as Hockney turned thirty in 1967 and which is surely the most erotically charged image in the show. Instead, Hockney’s young lover turns to stare at him from a bed within a similarly spotless interior, here dimmed to the blues of the night: he is lying prone on the sheets in his white T-shirt and his white sport socks, his left hand tensely opening and his bare buttocks gleaming in the moonlight. More tactile, though, than the painted boy and the stiff bed on which he lies is the fluffy mat beside it, where the brushwork frisks and teases.

This tryst in a nice neighborhood continues a romantic allegiance to Los Angeles set in motion in 1964. That year the young Yorkshireman, having sold out his first London show, traveled to the city of his hedonistic dreams and returned to recall his encounters with it in the studio. In California Art Collector (1964), it is the unfamiliar luxury of long-fiber carpets, as much as that of private swimming pools, that seems to have snagged his attention. Patches of wavy, watery brush rhythms ruffle the creamy primer at the base of the six-foot canvas, abutting other, denser paint patches—notably the chunky white and buff of an armchair fabric with floral patterning and the flamboyance of a carnation-pink wall. Between armchair and wall, we see the green of the collector’s dress surmounted by her head in profile, which turns to commune with a modernist sculpture while behind it another head, that of another sculpture, turns to face the opposite way.

Patches abutting, or patches laid side by side on a warm accommodating ground: these are ways that Hockney’s pictures are often pieced together. They become floors on which rugs have been strewn. Hockney displays a childlike delight in setting one type of content against another. In California Art Collector, floral chintz against green velour, the three discrete color blocks of that modernistic snowman, the stage-prop rainbow wedged between wall and distant pool; or in Hockney’s subsequent pictures of California pools, grids against undulations, translucent splashes against dense sun-soaked blues.

There is often also a certain mischief in his placing of pieces. The California Art Collector has sparks of friction where the crown of the carved head nearly nudges the roof edge and where the dowager’s bob doubles up as its beard. And arch, arty subtexts may attach to them: those in the know might recognize the former effect as adapted from Bridget Riley’s Kiss, a painting exhibited in London in 1962, just as the device of the lean-to roof alludes to the Piero della Francesca Nativity in the National Gallery. But the visual wit remains relatively innocent. That elderly art-adoring Californian might possibly be preposterous, a Margaret Dumont–style dimwit, but she also remains a thing of wonder, hieratic and alien. The young gay Englishman who conjures up her profile may be a flamboyant performer, but he is at the same time removed and circumspect, by nature an observer.

“Pictures with People In,” that first sell-out show of Hockney’s was called—a title that made it clear which of the two terms had priority. Pictures might potentially contain all sorts of things. The current retrospective of over sixty years of work—reaching back to a teenager drawing what he saw in the mirror in 1954—brings together portraiture, landscape, and still life in every kind of combination. It reveals a wonderfully resourceful artist, but one whose working moods have seemed to veer between studious and strident. The neat descriptive draftsmanship of that first sheet from provincial Bradford was succeeded by the declamatory mock-dumbness of canvases done at London’s Royal College of Art—We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961), for instance, with its Dubuffet-like puppet figures—that outrageously proclaimed a sexual allegiance British law was still intent to suppress.

Advertisement

The sweet-tempered and hugely popular productions of Hockney’s later twenties and thirties, epitomized by that 1971 London interior with the cat and the carpet, tilt back toward descriptive decorum. In the later galleries of the retrospective, the mood continues to oscillate. Between the ages of sixty-eight and seventy-six Hockney devoted much of his energy to rural scenes from his native Yorkshire. On the one hand, the venture led to pounding melodramas such as the sixteen-foot-wide May Blossom on the Roman Road (2009), with its gigantiform shrubs and super-vibrant hues, a Carl Orff orchestration of a placid English backwater. On the other, a 2013 sequence of drawings of lanes through a woodland are virtuoso solos of steady, quiet lyricism—charcoal’s whole gamut of streaking, stippling, and stumping attuned to the interplay of ground, foliage, and sunlight.

There is an inspiring buoyancy to Hockney’s act. Here is an artist who reckons he can get marks to perform however he pleases. His force of attention seldom slackens, and there will always be more to do. Picturing is his element, stretching in all directions. Each picture, in his own words, is “an account of looking at something,” but each has “a limit to what it can see” and thus tantalizes with the prospect of further viewpoints. Hockney might here be talking about the works of which this retrospective is composed, but he might equally be talking about the units of which they themselves are composed, the variegated patches of attentiveness.

The tension between acts of looking and their limits has thus worked in two ways. Between the debonair playfulness for which his painting became famous during the 1960s and the defiant energy with which he has been filling canvas after canvas over recent years, the happiest discovery of Hockney’s middle age was the “joiner,” or photographic patchwork, a procedure he hit on in 1982. Before this, painted portraits and landscapes—Mr and Mrs Clark, for instance—had often leaned heavily on camera shots, but here, multiplicities of little Polaroid snaps were themselves pasted onto boards, grid-wise or overlapping, each of them zooming in on aspects of the subject from slightly variant angles.

This straightforward tactic has proved highly adaptable. Among his Yorkshire landscape ventures, Hockney mounted nine video cameras on a jeep driven slowly down a wooded lane, repeating the journey through four seasons. The resulting four-wall, thirty-six-screen installation with its shuffling and shimmering disarray of foliage—fresh, full, falling, then snow-supplanted—is a delicious highlight of the show’s later rooms. The novelty of the sensation dispels any resistance we might have to the clichés about the annual round that lie behind it. Likewise, it is not exactly that a multiplication of Polaroids gives us greater insight into the artist-and-writer couple who sat for Don + Christopher, Los Angeles, 6th March 1982. It admits us, however, into the playful space of Hockney’s friendship with them with a breathiness unforeseen by his earlier, more formal double portrait of the same pair on canvas. The pile may not be particularly deep: nonetheless the rug has been ruffled.

Equipped with the versatility to picture however he pleases, Hockney chooses to picture whatever pleases him. He celebrates his friends and lovers, their agreeable homes and gardens, and places and particulars (an ashtray, a lampshade) that snag his workmanlike curiosity and ask to be disassembled and customized pictorially. If Hockney has thus become a recorder of styles and mores, he has been so unsystematically. After what he now calls his “homosexual propaganda” pictures of the early 1960s, little about the work has seemed specifically political: his responses to the AIDS crisis, for instance, can only be inferred obliquely. This is not to say that Hockney is without ideas about his art’s human purposes. On the contrary, his recent book written with Martin Gayford, A History of Pictures, argues that approaches to picturing such as his own aim to emancipate our imaginations, which might otherwise fall back into a “prison,” a disengagement from the world through which we move, a blinkering that makes it “look duller.”

The immediate culprit that Hockney names is the photograph. We err if we identify its evidence-packed surface with our own lived experience, because “the camera sees geometrically but we see psychologically.” But Hockney argues that this geometrization did not begin in 1839, when the invention of photography was announced: rather, Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti had devised the prison over four centuries earlier, when they developed the principle of single-point perspective implicit in any “account of looking at something” isolated by a fixed frame, whether that frame belongs to a camera lens or to the pictorial “open window” of which Alberti wrote.

Advertisement

Hockney’s hypothesis, first aired in Secret Knowledge (2001), is that the Western painting tradition from the fifteenth century onward leaned heavily but covertly on the visual texture of images isolated in this way and transcribed by artists from lens or mirror projections. One route by which artists might escape the resulting constriction of vision was by merging many transcribed projections into a continuous but nongeometrical composite. This, Hockney contends, is what we encounter in the high-definition paintings of Van Eyck or Caravaggio, which he regards as analogues to his own so-called “joiners.” More radical alternatives were offered at one end of art history by Picasso—for Hockney, his Cubism is an invigorating ruffling of the tradition’s otherwise glass-smooth picture surface—and at another by Chinese landscape handscrolls with their ever-roving viewpoints.

These were alternatives toward which Hockney turned in the paintings of his middle age. The retrospective includes a big jumbled interior, assimilating his Los Angeles house to Picasso’s Juan-les-Pins, and accounts of road journeys in which California and Yorkshire get remodeled as the Yangtze valley. They are weirdly unhappy projects. The old Chinese painters liked to invite the mind in, their emptinesses and near monochromes allowing it to roam without hindrance. By contrast, color in painting’s twentieth-century mainstream opted to blare boldly outward, the canvas as boombox.

This opposition of etiquettes was instinctively resolved when the younger Hockney detained cheeky gatecrashers—that carnation pink, for instance—within an affable foyer of off-white or raw linen. But a winding roadway sent through jangly patchwork topographies of viridian, orange, and cobalt presents viewers with little but sullen noise, neither welcoming nor challenging. The only way to move on from this, so it seems, was to pump up the volume. Hockney’s canvases of the Grand Canyon from the late 1990s glower vast and inert in their supersaturated reds, textbook demonstrations of the adage “more is less.” Hockney has been ever-nimble with a line, and a natural with every newly arrived technology (as a selection of merry little iPad drawings displays*), but at this stage, someone should have taken out an injunction to forbid him access to paint tubes.

How did such an honorable hard worker, one so alert to others’ high achievements, hit his head against this wall? Perhaps the problem arose out of romantic disappointment with the medium that had been so helpful to him in the happy paintings of his youth. “Photography has failed,” Hockney roundly declared afterward, when asked what was wrong with it: failed by comparison to handscroll painting in relaying lived experience and failed by comparison to oil painting in delivering memorable images. These, I note, are not expectations placed on photography by other painters of Hockney’s era. Gerhard Richter, Luc Tuymans, and others have been interested in camera images exactly because of their otherness from subjective vision and their haunting lack of substance.

Hockney, however, wants all images, however produced, to commit to a felt-for, moved-through world—for there is ultimately no other, he likes to think. “‘Reality’ is a slippery concept…because it is not separate from us,” he writes in A History of Pictures. The book is partly a lover’s quarrel with a seductive lens image suspected of backsliding on that commitment. At one moment in its informal but more or less chronological interpretation of art history, the camera obscura is credited with lending an added precision to the shadows in Chardin’s miraculous still lifes: three pages later, it gets blamed for the “dullness” of Thomas Jones’s Italian vistas.

A History of Pictures is in many ways a cherishable book. It is handsomely illustrated, and the art writer Martin Gayford, who has published a previous book based on exchanges with Hockney, here provides a linking commentary between the artist’s own remarks that is deftly phrased and researched with infectious enthusiasm. Gayford has an eye for out-of-the-way curios of art history and an ear for its campus talk. Moreover Hockney himself offers illuminating practical aperçus from a career that has taken in theater design and magazine graphics among much else, and that enables him to appreciate superior craftsmanship whether it comes from Rembrandt or Walt Disney. There is a great deal to learn from either author, if you open this volume at almost any page. Nonetheless, on reading it through I conclude, rather reluctantly, that its central premise is wrongheaded.

The factual issue of whether European painters employed projected images as much as Hockney claims we can leave to scholars—my own hunch being that Holbein (unmentioned here) surely did lean on them, whereas Chardin surely didn’t. Of more consequence is Hockney and Gayford’s wish to recategorize the painting tradition. We have become accustomed to regarding it as “art”—and thus attaching it to intellectual agendas that run from the Renaissance to conceptualism—but they argue that in a wider view, painting is better seen as a department of “pictures”—a bag it shares not only with photography but with cinema and illustrations of all forms. This is an understandable bid from a practitioner who, having reached a plateau of recognition in the art world during his youth, fell out with its increasingly conceptual mainstream from the 1970s onward and never wholly regained its critical approval, but who still has proved a robust survivor able to reach a public so wide that he is virtually immune from intellectual condescension. Look, he is effectively saying, my practice runs rings around your highfalutin theories.

But the maneuver hits two linked obstacles. One is that if, as Gayford rules, “abstraction…is outside our history of pictures”—excluded from it for not “looking at something”—then that history so patently lacks a handle on twentieth-century painting that it can be little more than whimsical. Figurative and abstract modes have intertwined at least as frequently and productively as canvases have with snapshots, California Art Collector, with its nod to the abstractionist Bridget Riley, being a minor instance to hand.

The other, adjacent problem repeatedly hovers in the margins. For instance, Hockney, discussing the almost undisputable use of lenses by Vermeer, adds that he

probably used similar techniques to many other artists. He just painted his pictures better.

Understanding a tool doesn’t explain the magic of creation. Nothing can.

We can all agree with that. But it is useful to give a cohesive term to such mysterious recognitions of quality, which is the point at which the word “art” gains its force. We dangle that notion over and above the extant records of production, those flattish rectangular objects, positing a principle higher and perhaps deeper than any particular picture of something.

At a time when such a notion of art feels particularly tenuous, with a sense of onward direction uniting few working artists, this Hockney retrospective in all its expansiveness could be taken as thoroughly apposite. Here is a model of a lateral approach to visual affairs, in which the video and the iPad lie side by side with the canvas and photo composite, all surfaces intended to please: for it is a fact of behavior that “people like pictures,” as Hockney remarks, and the more varieties of attentiveness that are laid out for inspection, the better that taste is serviced. The ground on which they are laid feels mildly warm and seldom hard, for resistant realities have no place here. Yes, Hockney, in marked opposition to nearly every major artist of his day, is an apostle of niceness and kindness.

Yet experience of the exhibition surely complicates this typecasting. To go from work to work is to discover how some rugs sink deeper than others, and that worthwhile art turns on depth, not on breadth. What flickers through the show’s finest pieces, flaring most vividly into life in images from 1960s California such as The Room, Tarzana but intermittent to this day, is an alternating current between attention and affection: a yearning that somehow to make could be to have and to share, checked by a suspicion that it can’t be. Marco Livingstone, a scholar with a thorough knowledge of Hockney, writes well in the exhibition catalog when he invokes “the key role played in the best of his art by the most admirable of all human emotions: love.”

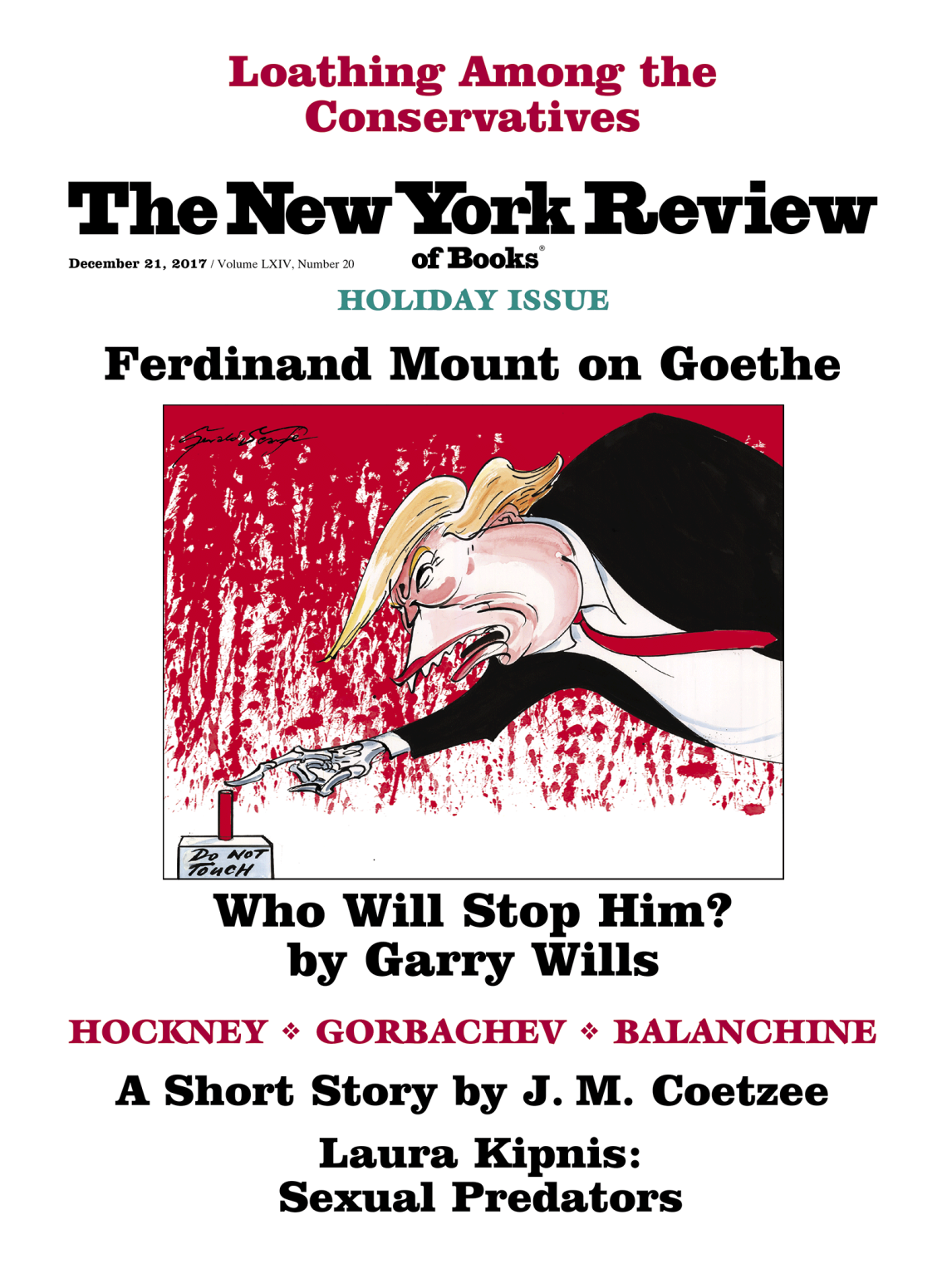

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna

-

*

Several of his earlier iPhone drawings were published in The New York Review; see Lawrence Weschler, “David Hockney’s iPhone Passion,” October 22, 2009. ↩