The tax legislation that was just rammed through Congress makes it quite clear that Donald Trump’s first year in the White House has been much more damaging to the nation than that of any other president in modern times. Before this bill, it might have been possible, though wrong, to argue that as president, Trump had brought to his office more sound and fury than action. The notion took hold for much of 2017 that his failures in Congress, along with a series of court rulings, had limited his impact; the failure to repeal Obamacare and the courts’ blocking of the early versions of his travel ban were cited as examples of the supposedly constrained Trump presidency.

No more. The sweeping tax bill gives a huge tax cut to corporations and to wealthy individuals, and will add roughly $1 trillion over the next ten years to the federal deficit. It will widen further the already enormous gulf between the very wealthy and the rest of America. And it sets the stage for an attempt by Republicans in Congress in 2018 to shrink the federal deficit by cutting benefits to a large number of Americans through reductions in Social Security, Medicare, and other social programs.

The end-of-year tax legislation forces a reexamination of quite a few other ideas about the Trump presidency that have taken hold from time to time over the past twelve months. One is the assumption that the Republicans in Congress and their leaders Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan viewed Trump merely as a temporary tool. Once the Republicans got the tax cuts they were so desperately seeking (so this argument went), they would prove more willing to move against him, to condemn his excesses and his outrages. But now that the tax bill has been completed, they seem more wedded to Trump than ever; they will need his support for, among other things, their budget-cutting efforts to follow.

So, too, the passage of the tax bill suggests a new look at the question of what might happen if Trump were to be replaced by Vice President Mike Pence. There has been a sotto voce line of argument among liberals that Pence would be even worse for the country than Trump. The logic of this was that Pence seemed more conservative than Trump and more beholden to financial interests like those of the Koch brothers; at the same time, he is closer to congressional Republicans and thus would be more able to get legislation through Congress. But the tax bill underscores the fact that Trump himself can get spectacularly regressive legislation through Congress; the supposedly “populist” streak that he occasionally displayed during his presidential campaign is sheer fiction, at least when it comes to economic policy.

More importantly, although Pence stands on the far right of the political spectrum, he at least is on the spectrum of ordinary politics, while Trump is not. His tendencies veer toward authoritarianism and white nationalism, with an overlay of conspiracy theories and hucksterism. Pence is a conventional, even boring politician, and while deeply conservative, he would bring with him far less of the racism and far fewer of the attacks on enemies, truth, and the rule of law that have proved so incredibly damaging to the nation’s social fabric under Trump.

Even before the tax bill, Trump’s first year had caused great harm to the nation. It is worth examining where he has had the greatest impact and where he has failed. Until the tax bill, many of the domestic proposals to which Trump had accorded the highest priority had run aground; either Congress failed to approve them or they were blocked in the courts.

He said he was going to do away with the Affordable Care Act on the first day of his administration, but it remains on the books today. It is sometimes argued that Franklin Roosevelt’s Social Security program, created in 1935, did not become accepted as a permanent feature of American life until two and a half decades later, when Dwight Eisenhower, the first Republican president after Roosevelt, finished his eight-year term without seeking to abolish it. In a comparable way, historians may someday come to view the Trump presidency as the time when Obamacare (or at least some of its central features, like required coverage for preexisting conditions and allowing children to stay on their parents’ policies until age twenty-six) became an established part of America’s health system.1

The wall along the Mexican border that Trump ordered to be constructed as soon as he took office is nowhere close to being built. He has not persuaded Mexico to pay for it, and at this point Congress hasn’t agreed to fund it either. Trump’s original plan to restrict Muslim immigration into the United States was blocked for most of the year in the courts. The plan had to be revised not once but twice; then, in early December, the Supreme Court allowed the third version of the plan to go forward while legal challenges proceed. As Trump’s top-priority initiatives got bogged down in the courts, so too did some of his other campaigns. Last summer, he announced on Twitter one morning that he was barring transgendered Americans from the armed forces. That policy too has been blocked in the courts.

Advertisement

Nevertheless, even when the courts have ruled against him or Congress has failed to do what he wants, Trump has inflicted considerable damage on domestic policy through his appointments and executive actions. The effects have been clearest and most lasting on the federal judiciary.

For most of the past year Trump trumpeted his early appointment of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court as one of his greatest successes. That was a largely hollow boast, since the person most responsible for the appointment was Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who had blocked President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Court throughout the previous year.

However, the harm to the judicial branch and Trump’s personal imprint on it are considerably greater when one considers the lower courts. By mid- December, Trump had appointed twelve judges to the US Court of Appeals, one level down from the Supreme Court, the most this early in any presidency since Richard Nixon’s. Virtually all of them are from the right. At the level of district or trial courts, Trump’s nominations have included figures like thirty-six-year-old Brett J. Talley, who has never tried a case and was unanimously rated “not qualified” by the American Bar Association. This proved too much even for Chuck Grassley, the Republican chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who refused to confirm him.

Meanwhile, a new proposal is being circulated by a right-wing legal scholar to expand the number of appellate judgeships (now 179) by two- or threefold, and to increase the number of district judges as well, with the avowed purpose of “undoing the judicial legacy of President Barack Obama.”2 In short, while the courts have served as an occasional constraint upon Trump during his first year in office, he is moving quickly to reshape the judiciary so that, in the long run, it may prove to be less independent and less constraining than it has been.

Elsewhere, across a range of environmental and regulatory agencies, Trump has appointed officials with a record of hostility to the idea that the federal government operates for the benefit of the public. The most prominent example is Scott Pruitt, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, who as the Oklahoma attorney general had repeatedly gone to court to block various EPA actions. Over the past year, Pruitt has introduced a series of initiatives favorable to the industries the EPA regulates, for example eliminating rules that limit carbon-dioxide emission. He has also repeatedly questioned the work of the EPA’s staff on climate change and other scientific issues.

It is a mistake to think that Trump has been causing damage only to a few specific regulations or areas of policy. The effects have been pervasive. One of the most detailed descriptions of what Trump has meant at the grassroots level comes from Michael Lewis, in a recent article in Vanity Fair about the Department of Agriculture.3 Inside the department, the effects of the new Trump era are registered division by division, program by program: cuts for the food stamp program, a weakening of the regulations governing school nutrition, looser rules for meat inspection, the politicization of the department’s science programs, instructions to the career staff to stop using the phrase “climate change.” All of this has taken place within Trump’s first year in office.

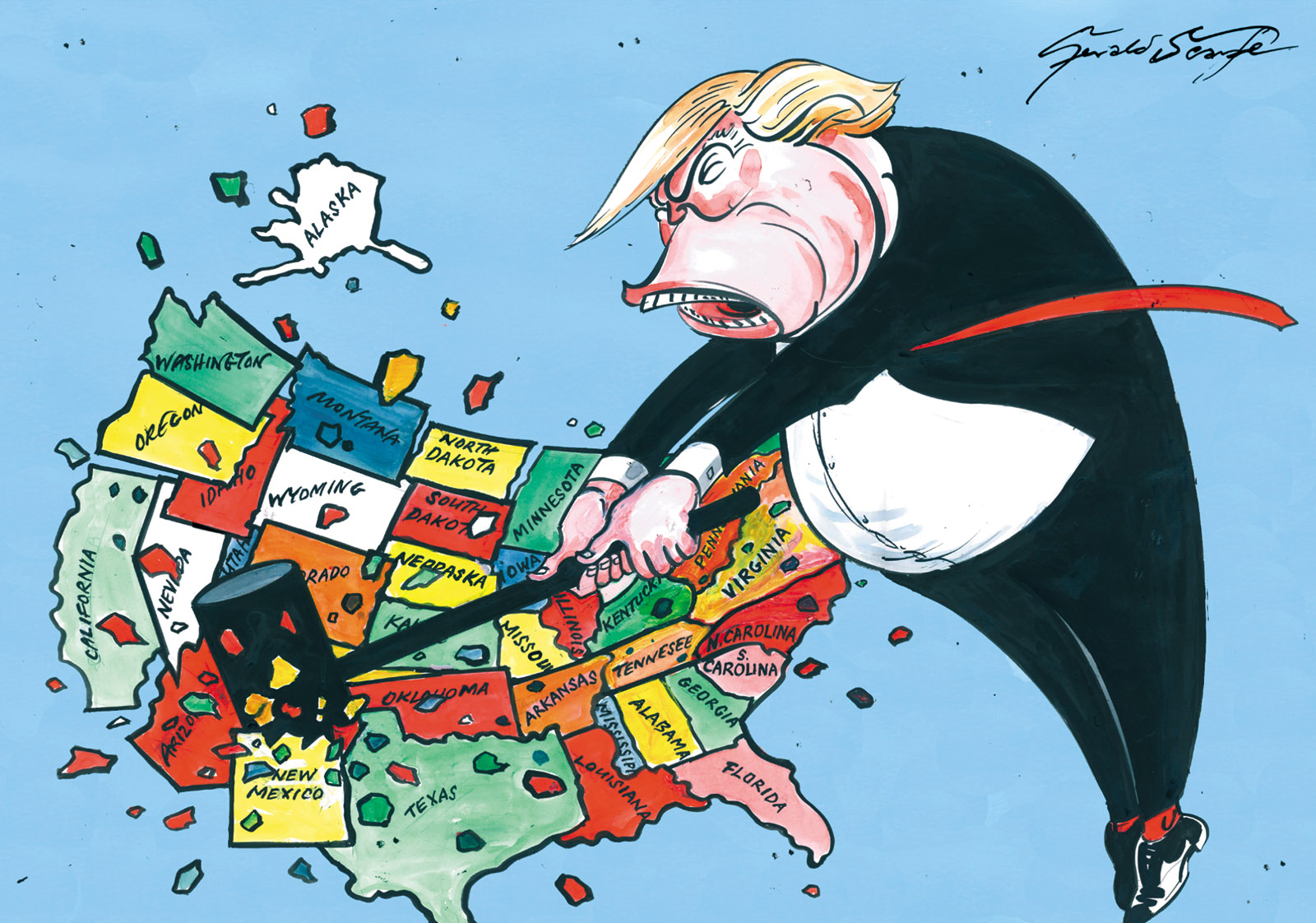

When it comes to dealing with the rest of the world, Trump has been a one-man wrecking ball, destroying many of the understandings, agreements, and relationships that have served as the foundation for American foreign policy for a half-century or more. The damage is not confined to specific policies: Trump has gone after the institutions that guide American foreign policy, especially the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency.

This has been a yearlong campaign, starting immediately after Trump took office. In his first week as president, he announced that the United States would withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the trade agreement the Obama administration had negotiated that was aimed at strengthening America’s ties with eleven countries in Asia and elsewhere. That decision strengthened perceptions in Asia of the US as a nation in retreat and thus helps China in its ambitions to become the leading power in the region. In December, Trump tore up decades of US policy by deciding to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. This threatens to harm America’s relations with nations in the Middle East that have long supported US policy, such as Jordan and Egypt. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas said following Trump’s announcement that there will no longer be a role for the United States in the Middle East peace process.

Advertisement

Far-reaching as they were, the decisions on TPP and Jerusalem merely served as bookends for the many foreign policy changes in Trump’s first year. During 2017, he also withdrew the US from the Paris accord on climate change. He became the first US president to waver on America’s commitment to NATO, refusing to say on his first trip to Europe whether the US would abide by Article V of the NATO treaty, which provides for collective defense. (In that case, he later came around after repeated prodding by his foreign policy team.) He roiled America’s closest neighbors by ordering a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Beyond this undermining of past policies and agreements, Trump conducted himself in ways that eroded America’s friendships with other countries and their leaders. His penchant for confrontation extended even to America’s closest allies (indeed, more to allies than to adversaries, since he mostly held back from challenging Vladimir Putin or Xi Jinping). Eight days after he was sworn in, he engaged in an icy phone-call standoff with Australian Prime Minster Malcolm Turnbull. (“I have had it. I have been making these calls all day and this is the most unpleasant call all day. Putin was a pleasant call. This is ridiculous,” the new president told the leader of America’s closest friend in the Asia-Pacific region.) In late November, Trump outraged the British public and drew a public rebuke from Prime Minister Theresa May when he retweeted incendiary, inaccurate anti-Muslim videos posted by a leader of the far-right group Britain First.

Along the way, there were Trumpian dustups with Mexico, Germany, and South Korea, among others. Trump regularly suggests that America is paying too much for its alliances and agreements, and that other countries aren’t paying enough. It sometimes seems as though he believes that we don’t need allies and would be better off without them. America’s closest partners have responded accordingly. Early in December Sigmar Gabriel, the German foreign minister, said that the Trump administration has come to view Europe as a “competitor or economic rival” rather than an ally and that relations with the United States “will never be the same.”

In cases where his policies aren’t entirely new, Trump’s style—his pattern of tweets and personal insults—has added a new dimension to them, with unpredictable results. The biggest foreign policy challenge of his first year came from North Korea’s rapidly developing nuclear weapons program. Trump’s threats to use force against North Korea were not a departure from past American policy; under the rubric of “coercive diplomacy,” previous administrations have also considered possible military action against North Korea. But Trump went a step further by taunting North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, calling him “Little Rocket Man” not only in tweets but in formal settings including the United Nations General Assembly. He even threatened that he would “totally destroy” the country.

In the midst of these policy upheavals, Trump was responsible for the most unstable foreign policy team of any president since World War II. His first national security adviser, Michael Flynn, lasted less than a month in office before he was forced to resign, and by the end of the year had pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI. At this writing, it appears that Tillerson may also be headed for a tenure shorter than any secretary of state in modern times: a series of reports in early December said that Trump would be replacing him within weeks. While Tillerson is still there, Trump has consistently undermined him. One day Tillerson states that the US is ready to talk to North Koreans. The following day, the White House says the exact opposite.

US foreign policy can survive some personnel upheavals, but Trump has done institutional damage as well to the organizations that are responsible for shaping America’s relations with the rest of the world. At the time he took office, Trump’s principal target was the CIA, which he and his supporters accused of being part of a “deep state” conspiracy against him, an attack prompted by the agency’s reports on Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election. He continued throughout the year to attack the CIA, accusing it of being partisan or biased and its former leaders of being “political hacks.”

The harm at the State Department was worse. Tillerson appeared to be the sort of corporate hatchet man who is brought in from outside to cut the staff as drastically as possible, before he is himself transferred away. With Trump’s evident support, he left a wide array of senior positions vacant for most or all of the past year. That meant, for example, that he dealt with North Korea without either an assistant secretary of state for East Asia or a US ambassador in South Korea; the US still does not have an ambassador to Egypt, whose government is beginning to deal with the Russian military once again. The result of the State Department’s short-handedness is that ever more policy is being made by overtaxed officials at the National Security Council and the White House, which is apparently the way Trump wants it. The vacancies are merely the top of the heap of rubble at the State Department; Tillerson has acceded to a wave of deep budget cuts that eliminate large numbers of positions throughout the department.

Worst of all has been the harm Trump’s America First foreign policy has caused in the realm of ideas. Over the past seven decades, the United States at least professed to stand for principles of human rights and democracy (although American policies did not always live up to those ideals). Under Trump, the ideals have been all but abandoned. He seems to believe only in commercial advantage, and rarely if ever makes even a touchstone reference to human rights. The major countries he has courted most assiduously, avoiding confrontation wherever he can, have been autocratic regimes: China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Whether coincidentally or not, these also happen to be three countries with large sums of public or private money to invest overseas.

The greatest damage done during Trump’s first year concerns neither domestic nor foreign policy, but something far deeper: it is the harm he has caused to America’s political system and to the democratic norms that underlie it. No evaluation of the impact Trump has had as president could be complete without addressing his attacks upon the rule of law, upon notions of political and racial tolerance, upon national unity, upon the freedom of the press, upon civil discourse, upon truth itself. The result has been to fray the bonds that hold American society together.

Trump has abandoned the very notion of civil discourse by refusing to accord his political opponents even a minimum level of respect. No other president in modern times has so insistently portrayed his adversaries as dishonorable. The usual practice of ordinary democratic give-and-take seems alien to him. At various times, usually through his Twitter account, he has responded to criticism by lashing out at Republican senators such as John McCain, Mitch McConnell, Bob Corker, and Jeff Flake, as well as his attorney general Jeff Sessions, disparaging their motives, their character, their height (Corker, Marco Rubio), or their ancestry (the US district judge Gonzalo Curiel, impugned because of his Mexican-American background). Other presidents have aspired to become moral leaders; Trump has become America’s chief thug.

He has seriously undermined the rule of law and the very principles of democracy by calling for the investigation and prosecution of his political adversaries. The cries of “lock her up” that marked his 2016 campaign against Hillary Clinton (which were denounced at the time, even by prominent Republicans, as typical of a banana republic) have evolved in 2017 into his repeated suggestions that the Justice Department should go after her (with, now, the support of many Republicans).

Trump fired the FBI director, James Comey, after he resisted Trump’s pleading to go easy on Michael Flynn. At this writing, it is not clear whether he will try to fire Robert Mueller, the special prosecutor who took over from Comey the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. But by early December, his supporters were engaged in a campaign, with his evident support, to undermine the legitimacy of both Mueller personally and the FBI as an institution. When his travel ban was blocked in the courts, Trump responded by denouncing the judges. So much for the independence of and respect for the judiciary.

Trump has shown even less willingness to respect the constitutional validity of another American political tradition: an independent press as a restraint and watchdog on government. Any stories he doesn’t like are dismissed as “fake news,” along with the news organizations that have published or broadcast them—the very word “fake” underscoring that he refuses to recognize their legitimacy. Beyond the press, Trump seems to reject the concepts of objective truth, rational discourse, and scientific expertise, the Enlightenment ideals on which this country was founded. From the earliest days of his administration, he has asserted his own contrary-to-fact versions of events even when plain, verifiable evidence proves otherwise. Consider, for example, his claims that the crowds at his inauguration were bigger than those for President Obama, or his insistence that he won the popular vote in the 2016 election.

Finally, Trump has sought, repeatedly and deliberately, to sow divisions. He has attacked one group after another: Mexicans, Muslims, protesting black athletes. In the process, he has brought to the surface some of the raw, ugly emotions of hate in America that in ordinary times lay more or less suppressed, and has given presidential validation to racism and nativism, along with hostility toward education, science, and professionalism.

The effects are poisonous. If the United States were to face some sudden crisis—an attack overseas or at home, an economic collapse—Trump, like any president, would need to summon forth a sense of national unity in response. He would instead confront the sullen, divided nation he has so steadily provoked. Even if there is no such national emergency, the divisions he has created could last, harming the nation for years after he leaves office.

It is frequently said that through his incessant bellicosity, Trump is “playing to his base,” but that explanation raises more questions than it answers. His base represents less than 40 percent of the country. The election results of the past two months, particularly in Virginia and Alabama, demonstrate the limitations of merely exciting his base; by themselves, his core supporters are usually not enough for victory. Why, then, does Trump not try to expand his support in the way that other presidents have often done? (Bill Clinton’s strategy of “triangulation” comes to mind.)

One unsettling possibility is that Trump believes that somehow, in some future crisis, his polarizing approach may succeed in galvanizing the country into some new political constellation in which his base of 35 to 38 percent will suddenly jump to a majority. Another possibility, even more disturbing, is that we are witnessing a strategic embrace of rule by minority: Trump may believe that his judicial appointments and his favoritism toward the donor class of the wealthiest Americans, when combined with political tactics like gerrymandering and voter suppression, will enable him to govern and win reelection without ever gaining anything close to a popular majority. The third possibility is that there is no strategy at all; Trump cannot expand his support simply because he is by nature unable to do so. He can manage to convey only anger, resentment, and prejudice; he lacks the ability to heal divisions, to win over those who oppose him, to seek common ground.

On the day after Trump was sworn in, more than a million Americans turned out in protest demonstrations in Washington and other cities across the nation. The harm he has caused to the nation since then is severe enough to justify demonstrations many times that size. Street demonstrations, though, cannot remove Trump from office. He will stay on, most likely, for four or eight years, until he is defeated at the polls or removed from office through impeachment or the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. There are now extensive debates among Trump’s many opponents about which of these approaches to pursue. They involve serious questions of tactics and strategy that are beyond the scope of this article.

After Trump’s first year in office, what is clear beyond doubt is that the damage he is causing to the nation, to its domestic and foreign policies, and even more to the rule of law, to its constitutional system, to its social fabric, and to its very sense of national unity, is piling up week by week. The longer he stays, the worse it will get.

—December 21, 2017

This Issue

January 18, 2018

Divine Lust

This Land Is Our Land

-

1

Both Trump and the Republican Congress have sought to weaken the Affordable Care Act, Trump with an executive order eliminating some subsidies to insurance companies and Congress in a provision of the tax bill eliminating mandated coverage. But the law still stands. ↩

-

2

See Linda Greenhouse, “A Conservative Plan to Weaponize the Federal Courts,” The New York Times, November 23, 2017. ↩

-

3

“Inside Trump’s Cruel Campaign Against the USDA’s Scientists,” November 2017. ↩