The “street” in “street photography” does not refer to a location or a subject; it identifies an idiom. A street photographer walks into situations nobody controls in order to discover what can be made of them as pictures. She commits to contingency as a coauthor, as war photographers do, but her object is art, not news. A street photographer is a central, even if unseen, character in every scene she records. Any human gesture in a street photograph—a swinging arm seen from this angle, a planted foot from that one—results from the posture and movements not of the subject alone but of two people, photographer and photographed.

The characteristic gestures in the street photographs of Helen Levitt marry grace with awkwardness—folded limbs, trailing skirts, feet acutely angled as someone turns around. The sidewalks in her world are dirty, the curbstones cracked, doors and walls pockmarked and chalk-marked. The vacant lots where kids go scampering are generations deep in shattered things.

Some of these features of Levitt’s work can be accounted for by her explanation—meant to repel any imputation of a do-gooder’s motives or, in her images of children, motherly tenderness—that she photographed in poor neighborhoods because that’s where life happened in the streets, and kids were simply the people she found out and about. But some of its features, too, must be declared matters of style. In an essay written in the 1940s for what would become Levitt’s first book, A Way of Seeing (1965), James Agee positioned her street pictures as “lyrical photographs” as opposed to “social or psychological document[s].” Levitt summarized the capacity that allowed her to make her pictures: “I can feel what people feel.”

A lifelong inner ear condition gave her what she called a “wobble”; she also had, as a jazz pianist or horn player might have, an affinity for irresolution, missteps, in-between shiftings of weight, the moment not at the apex of a jump but just after. Her pictures say: Things don’t line up. Bodies have minds of their own. People interact in a richer, more expressive way in life than they ever will on a stage; the hard and worthwhile part is catching them at it. In the 1930s Levitt sometimes outfitted her camera (as Ben Shahn and Walker Evans also did) with an angled prism that let her appear to be photographing 90 degrees off what her lens was taking in. This kept her subjects from reacting self-consciously to the camera, but it also must have gotten her at least half engaged in peripheral vision.

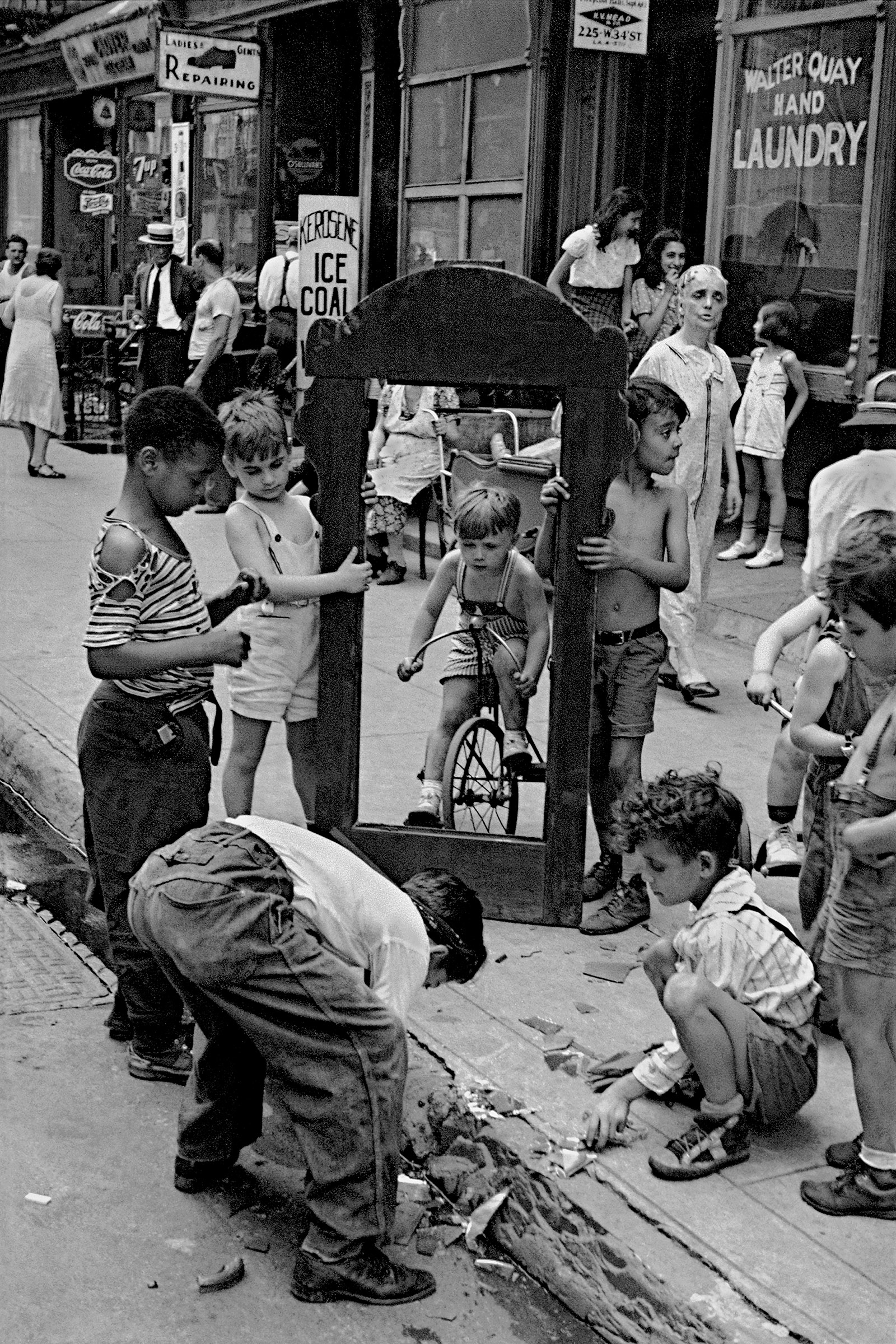

A photograph Levitt made around 1940 has the kind of elegant internal logic that invites protracted discussion and tempts bloggers and teachers of art history surveys to let it stand for her work as a whole. Nine children on a summer sidewalk are playing with the scavenged parts of a half-length mirror. The photographer, standing a few feet out in the street, has a nearly straight-on view through the heavy wooden frame, which is held upright (reasserting the format of the overall image) by two shirtless boys to its left and right. Within and behind the frame—taking the place of the artist’s reflection—is a boy on a tricycle, who looks through the frame and down at an older boy in the foreground, stooping to collect shards from the gutter. In the background, a world of adults and older children occupies itself amid storefronts and signage, underlining the self-containment of the scene. Every detail of the photograph contributes a note to its fullness, without ostentation or overlap or, most remarkably of all, the least whiff of premeditation.

If anything is wrong with using this endlessly remarkable photograph as an epitome of Levitt’s art, it is that apotheosis seems foreign to her nature; most of her images traffic in the simpler, looser observations of an unbiased eye on the move. A new collection of Levitt’s photographs, One, Two, Three, More, errs on the everyday, miracle-free side of her work. A few dozen of the book’s previously unpublished images might even prompt longtime admirers to ask: Is this picture a failure that should have been left in the box? Or on the contrary: If Levitt had published this image decades ago, would I ever have questioned how remarkable it is?

At the center of one such photograph, a figure is darkly reflected in a vertical pane of glass—a shop door that stands slightly ajar. (See illustration above.) Even on repeat viewings I want to read the reflection as the photographer’s. In fact it belongs to a woman who stands to the left of the door, raising a handkerchief to her face in a gesture that recalls that of a camera operator. She and the man beside her gaze toward something out of sight, beyond the left edge of the image. In the lower-right corner of the scene, a seated man casts his glance in the opposite direction, out of frame to the right. If the children, entranced by their empty mirror frame, embody the collective absorption of a tribe, these adults are the very image of distracted anomie. The glass-faced storefront behind them forms a frieze of seven narrow facets that only just fail to cohere.

Advertisement

The book’s most anomalous image portrays a trio of women, dressed for hot weather and bending over to search in the mud at the marshy edge of a body of water. They occupy the immediate foreground in profile, Babylonian-style, holding three poses that are sufficiently alike to signify their engagement in a common cause. Behind them, a stand of rushes carries one’s eye to a rocky bluff in the distance, upon which other figures appear, outlined against the sky. This is no Manhattan scene, nor is it clear where we are in time, but Levitt’s voice comes through in the kind of attention the image pays—not exactly to the women (one doesn’t see enough of them to wonder who they are) or to the place (no photographer ever cared less about landscape), but to the way a space is defined by the human things going on in it.

Levitt was born in Brooklyn in 1913. She was in her early twenties when she began thinking of the camera as a possible way into art. Her inspiration was seeing Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery. At that time, the mid-1930s, advertisements promised that the Leica 35mm camera, which Cartier-Bresson used, would enable anyone to “catch the ‘fleeting moment.’” In 1952, Cartier-Bresson’s landmark monograph, Images à la Sauvette (Unlicensed Images), would be published in English as The Decisive Moment. Starry formulations such as “the fleeting” and “the decisive” lay far from Levitt’s down-to-earth view of her métier, but from the early years of her career to the present “the moment” has continued to be regarded as the crucible of meaning in street photography. In a street photograph, an artist of quickened senses appears to have extracted, in real time, enduring art from the inchoate actions of passersby.

But if a photograph is the deposit of the instant stored in the negative, it also reflects insights and actions from before and after that moment, enacted on less hurried scales of time. Some of those choices, though just as specific to the medium as a shutter’s instantaneity, get downplayed in heroic accounts of the photographer’s art.

After deciding where to be with the camera (Mumbai, say, or Midtown), an artist decides when and how often to press the shutter release. This act does not always indicate a “decisive” grasp of what is happening; it might be a way of asking a question. Later come decisions about which negatives to print and which to suppress—choices that can be revisited throughout a photographer’s life, and even after it. At any time, too, one can decide or redecide whether and how to crop the original composition, and how to manage in the darkroom countless subtleties of contrast and emphasis. The artist, or someone, has to decide how large to print a picture, and subsequently publish it. No less substantial are decisions about how to pair, sequence, caption, title, or otherwise give a structured setting to the image. All of these choices—some based on others preceding, others quite independent—can add up to a substantial revision of the camera’s ostensibly “momentary” account.

Levitt’s case provides an occasion for recognizing the contrast between the “moment,” in which photographic criticism has invested so much, and the long, unusually elastic timescale that photographic authorship allows for. Right up until her death in 2009 at age ninety-five, Levitt was continually revisiting the exposures she had made on the street sixty or seventy years earlier—work that continues to come to light in books such as One, Two, Three, More. She had every right, of course, to remain engaged with her early negatives, but it is sensible to distinguish between the young artist doing her first street work, the middle-aged one shaping it into book form, and the nonagenarian approaching it with a lifetime’s experience.

Masters of street photography tend to move around a lot. Restlessness figures in their public image: their creativity looks indivisible from wanderlust and from the portability of the handheld camera. Beginning in Africa in 1931, Cartier-Bresson traveled widely and constantly, creating pictures so intimate and subtle that the entire world seemed to have fallen under his artistic spell. In the course of two rambling road trips between 1955 and 1956, Robert Frank produced a sequence of images that reads like both a highly personal travel diary and a pictorial concordance to American sensibilities. Lee Friedlander has been photographing continuously since the early 1960s, extending the reach of his art with each thematic project. (His recent subjects in book form have included show-window mannequins entangled in reflections of the skyline outside and roadside views framed in the driver’s-side windows of rental cars.)

Advertisement

Amid this company, Helen Levitt is notable for having photographed almost nowhere but in the streets of two neighborhoods in New York City. Except for a 1941 trip to Mexico and working expeditions by subway (with her friend Walker Evans in 1938 and on her own after 19781), she created nearly her entire published body of work on the sidewalks of Harlem and the Lower East Side, as often as not photographing children. In the introduction to A Way of Seeing, James Agee translated the narrowness of Levitt’s beat into the makings of a photo-mythology: in their roughness and anonymity, he wrote, her street settings stand for “the world.” That world’s denizens—Levitt’s people tend to be powerless, poor, and, in his dubious phrase, “pastoral”—pantomime the adventures of the soul at large in a mortal realm with no fixed home or occupation. For Agee, Levitt’s work is about humanity’s tenuous claim on a state of grace that is embodied in the play of children. Thus, for example, he describes a sequence of images that segues from the rampages of children to scenes of awkward adolescence: “Subtly, ineluctably, the quality of citizenship in this world where all are kings and queens begins to shift and, almost invariably, to decline and to disintegrate.”

Agee’s perspective on Levitt’s work, as he conceded, was willfully personal and “extravagant.” It stands in contrast to her own remark on street work: “It was like collecting. When you see something you grab it.” Different as the two accounts are, they are not irreconcilable; one might even say that Levitt’s best pictures stick in the mind by sustaining a mental dialogue between something like Agee’s register of metaphor and Levitt’s own radically literal perspective on what her pictures disclosed. When Levitt said, “All I can say about the work I do is that the aesthetic is in reality itself,” she was either effacing her part in it or bragging, or both.

The plates in One, Two, Three, More are preceded by a note: “The photographs in this book were made between 1934 and 1946, mainly in New York City.” These years define the first phase of Levitt’s street work; she would take up the still camera again in the late 1950s, after years making a living as a film editor. From the start her work was characterized by a canny unshowiness. Many street photographers seize on easy visual dramas between up-close and far-off by wading into the middle of the action. Levitt tended to hold back, letting her people occupy an arm’s-length, middle-ground zone, where it was easy to keep them clear of the camera frame. Her spacious, lucid staging habits lend the gravity of theater to the simple actions that attracted her, such as looking across the street or resting on the fender of a truck. Finding fault in her street scenes would be as contrarian as telling a rock critic you have no use for the Beatles.

If Levitt’s hands-off manner has aged better than the higher-energy methods of street photographers as various as Lisette Model, William Klein, or Garry Winogrand, her reputation has benefited, too, from her rigor as a self-editor. Levitt did not live by publishing magazine features or books, and she released new work only when satisfied with it. A series of mishaps delayed the publication of A Way of Seeing until twenty-two years after the 1943 exhibition it reflects (“Helen Levitt: Photographs of Children” at the Museum of Modern Art), and that book served for roughly another two decades as the main public record of her work. (A second edition in 1981 added twenty-four plates; a third, in 1989, twenty more.) Otherwise she published sparingly, despite ongoing activity in both color and black-and-white and a run of museum and gallery shows that began with a 1974 MoMA exhibition of new street work in color. Only in this century, when she was in her eighties and nineties, did Levitt at last publish substantial new collections of work, which she gathered from throughout her career, relying on the printer Chuck Kelton to meet her demanding specifications in rendering the images.2

These late-in-life volumes remained faithful to a format Levitt established for her books in A Way of Seeing: a brief, literate, unillustrated preface, followed by an unbroken sequence of uncaptioned photographs, one per page at matching scale. As a mode of presentation, this formula is (as the artist herself was) almost invisibly low-key, but it nonetheless conveys a message by casting the holder of the book as a reader. As you make your way through these volumes, encountering photographs two at a time, you never run up against any kind of showy graphic gesture; each image simply holds its page, facing its partner civilly, like the anthologized works of a short-form poet.

By contrast, Evans and Frank, in their respective monographs American Photographs (1938) and The Americans (1959), positioned their pictures on right-hand pages only. Dates and titles (always minimal: usually just a place name) are present but set apart from the pictures, in section lists or at the bottom of a facing page. This is the template for an art book or a museum catalog, and its earnest theatrics (all those blank left-hand pages holding their breath) would be wrong for Levitt. So too would the picture-magazine-based format Cartier-Bresson employed in his oversize monographs, in which the spreads accommodate anywhere from one “double-truck” image spanning the gutter to four photographs at a time. Levitt’s books decline to be catalogs or magazines; instead, they are Levitt’s way of showing that looking at her photographs, or looking around the city, is like reading a book.

A National Public Radio correspondent, Melissa Block, has recounted that in a 2001 visit to Levitt’s apartment, she spied a box of working prints labeled “Here and There.” (The book of that title would appear two years later.) When Block asked to peek inside the box, Levitt replied: “Nope. Cause I’m unsure about it. If I was sure that they were worth anything, I’d show it to you. But I can’t.” It sounds as if the box contained proof prints, of the kind Levitt made for herself as a way to audition exposures, new or old, and decide whether they merited further attention.

The images in One, Two, Three, More are drawn from among Levitt’s proof prints, some signed, others not. By my informal count, about twenty of the 176 photographs in the book have appeared in print previously. Around a dozen more are variants—neighboring moments—of frequently published images, including a group of Halloween maskers descending a stoop, an angel-faced boy cradling a toy pistol, three kids chasing one another through an empty lot with a tree branch, and two nuns in conversation on an East River pier.

These outtakes afford valuable glimpses of Levitt’s working methods in the field. They undercut the notion that she seldom pressed the shutter more than once at a given scene, even while they confirm the rightness of her original instincts about which negative to print. (Kelton, to whom Levitt would bring strips of film for printing, observes that she seemed to work both ways without favoring one over the other. A memorable frame might show up on a whole roll of one-offs; in other cases Levitt would shoot a dozen frames or more in one spot, or stalk a likely prospect through the streets.)

How would Levitt feel about the airing of her also-rans, and how should we? Geoff Dyer’s warm but dispensable introduction does not raise the question. One imagines that the artist—whose strong suit was never printing—would have been better served by a presentation that put these images forward as leaves from a notebook, rather than undiscovered but (as too frequently they are) unremarkable works. By way of explaining her success rate, Levitt once noted that she “never had a project”; every moment, every subject, had to earn its way into her attention. So it is, counterintuitively, fascinating to see all these graphically negligible lonely dog-walkers (seven of them), emotionally ambiguous couples, and amorphous gatherings on stoops. Young artists might feel cheered to discover that Levitt had slow days when she shot more or less by rote, and what is more, that she was still asking herself seventy years later whether she’d got anything good.

The book’s title refers to the four sections into which its plates are divided. One realizes with dismay that those numbers indicate how many people are in the pictures. Thus fifty-five loners (One) are followed by fifty-three pairs, thirty-five trios, and thirty-seven groups of four and up. This clumping of photographs on such a simple basis undermines the subtlety of Levitt’s art for what feels like a trivial and distracting trick, flattening 180 diverse images into chapters that often grow tedious. Why do this? (The book’s editor, accidentally uncredited on the colophon, is its designer and Levitt’s longtime co-editor, Marvin Hoshino.)

Though perhaps intended only as a fresh variation on the format of a Levitt book, this choice has one more effect, possibly unintended but, in the end, worthwhile. You will not want to read One, Two, Three, More straight through, as if it were just another Levitt book. As of course it is not: the author is gone. Think of it, instead, as something more modest, individual, and intimate: an appendix of half-rejected, half-resuscitated exposures, an afterword, a commentary, a loving farewell, to be dipped into here and there and adventured in, like a neighborhood where you enjoy going walking to watch the people.

This Issue

February 22, 2018

God’s Own Music

The Heart of Conrad

Doing the New York Hustle

-

1

Some of these photographs have just been collected in Manhattan Transit: The Subway Photographs of Helen Levitt, edited by Marvin Hoshino and Thomas Zander with an introduction by David Campany (Cologne: Walther König, 2017). ↩

-

2

See Crosstown, with an introduction by Francine Prose (PowerHouse, 2001); and Here and There, with a foreword by Adam Gopnik (PowerHouse, 2003). ↩