Louise Erdrich’s novels, many of them set on Native American reservations, take seriously Faulkner’s notion that the past is neither dead nor buried nor, even, past. In the words of Erdrich herself, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and the author of more than twenty books, “history works itself out in the living.” Her most recent books—The Plague of Doves (2008), The Round House (2012), and LaRose (2016)—form a loose trilogy that share a setting (a reservation on the Ojibwe territory of North Dakota), characters (including Mooshum, the randy ancient patriarch in Doves and Round House), and a preoccupation with inheritance.

Violins, grudges, memories, and tribal membership are passed down through generations, striking each recipient with the full force of their origins, sometimes even transcending the borders of one novel to reach into the next. Oppression, too, is imparted: the lives that Erdrich depicts are fundamentally shaped by continuing injustices that many Americans—living on stolen land and reaping the rewards of stolen labor, while embracing an ideology of meritocracy that assures us that we deserve our privilege—prefer to think of as strictly historical. When the federal legal system fails, in Erdrich’s books, to recompense Native victims of crimes, justice is pursued outside the law. A boy kills his mother’s rapist; an accidental murderer lends his own child to the grieving parents of the boy that he killed.

The Future Home of the Living God shares the concerns of Erdrich’s earlier work, but transposes them into an imaginary future. The history that “works itself out in the living” is our present moment, and the crime that is extra-legally punished is the violence that humans have wreaked on the environment. For millennia we’ve manipulated the planet to our benefit—cutting down forests, drilling deep, mockingly camouflaging mountains of trash and cell towers with grass and leaves—and now it is seeking revenge. “Mother earth,” one character says, “has a clear sense of justice. You fuck me up, I fuck you up.”

This new novel, Erdrich’s first explicit foray into nonrealist fiction, is the diary of Cedar Hawk Songmaker, addressed to her unborn child and written with the intention of documenting a momentous period in history. “Apparently,” Cedar tells us in her first entry, “our world is running backward. Or forward. Or maybe sideways, in a way as yet ungrasped.” The novel remains frustratingly vague about what exactly this entails, but according to DNA experts whom Cedar watches on television, “small-celled creatures and plants have been shuffling through random adaptations for months now.” This shuffling is apparently compromising the reproductive process. For some time dogs have stopped “breeding true,” and rumors abound of similar problems in humans—a stark concern for Cedar, who begins the book four months pregnant.

Against the novel’s background of genetic rearrangement, Cedar experiences an upheaval of her own, as she visits her Ojibwe birth mother for the first time. Growing up in Minneapolis, she had idealized her origins. Her adoptive parents, Glen and Sera Songmaker—“happily married vegans” and “Buddhists, green in their very souls”—gave her a conspicuously Native American–sounding name, kept her hair in braids, and celebrated her identity as an “Indian Princess.” At school, she was

mentioned in the setting of reverence that attended the study of Native history or customs. My observations on birds, bugs, worms, clouds, cats and dogs, were quoted. I supposedly had a hotline to nature.

This stereotype-woven scrim comes apart when Cedar goes to college and meets other Native American students, who tell her about the crises around which they grew up: “Addictions. Suicides.” A letter that Sera gives Cedar from her birth mother, Mary Potts, further disrupts her self-conception. The Pottses, it turns out, are neither “the romantic imaginary Native parents” Cedar had invented, nor the poor, alcoholic parents she learned about in college. “We were bourgeois. We owned a Superpumper”—a gas station supermarket.

Defying the wishes of her adoptive parents—who warn her of debates in Congress about “confining” certain people in response to the recent genetic discovery—Cedar drives to Mary Potts’s house on a reservation in northern Minnesota to “pump the family for genetic information” that might be relevant to her pregnancy. The Potts family makes a motley team: the ancient Mary Potts Senior, reminiscent of the wise centenarian matriarchs and patriarchs who populate Erdrich’s other novels; Eddy, Mary Potts’s husband and Cedar’s stepfather, who reads Dostoevsky at the Superpumper and is writing a Knausgaardian memoir, parts of which are transcribed in the text, in which he enumerates his daily reasons for not committing suicide; Little Mary, a moody teenager whose breath smells like drugs and whose bedroom floor is covered in layers of crusty clothing two feet deep; and Mary Potts herself, called Sweetie, who takes care of the family, has a pretty face and a heart-shaped butt, and uses overtly intelligent words like “feckless.”

Advertisement

During her stay, Cedar again encounters a discrepancy between the pervasive spirituality associated with Native life and its socioeconomic reality, as, for instance, when Sweetie goes before the tribal council to present an earnest proposal for erecting a shrine to “Kateri Tekakwitha, Lily of the Mohawks, patron saint of Native people” to attract the tourism money of pilgrimage crowds: “The sacred oval of earth lies between the north and south parking lots.” The “sunset tour of the reservation” consists of walking “up the candy and condiments aisle, down the utilities and snack foods aisle” of the Superpumper.

In the first part of the novel, while nature’s devolution remains rather foggy and before it significantly affects Cedar’s story, Erdrich masterfully builds an eerie environment in which everything is just a little amiss. When Cedar reassures the Potts family that she’ll be able to find their house on GPS, they respond: “We ain’t on no GPS, and Siri’s dead. You don’t know?” It’s never made clear what Cedar doesn’t know, and Siri’s death never comes up again, but the effect is chilling (and the fact that a computerized woman’s death reads like an apocalyptic event suggests that we ourselves have come close to the future as earlier science-fiction writers envisioned it).

Watching TV shortly before reuniting with her adoptive parents, Cedar is panicked by its homogeneity: all the people she sees onscreen are “white with white teeth”;

there are no brown people, anywhere, not in movies not on sitcoms not on shopping channels or on the dozens of evangelical channels up and down the remote. Something is bursting through the way life was.

This impression of whitewashed media will feel familiar to anyone who has watched cable TV in America. But it is presented as an alien development, symptomatic of something gone horribly wrong. A week and a half later, Cedar calls her adoptive parents, but the “overly pleasant voice” on the other side of the phone is “not my mom’s, but it is familiar. Fulsome, full of inquiry, too avid.”

The science-fiction conceit continues to unfurl at a slow, creepy, meditative pace. Cedar observes haunting symptoms of the world’s crisis and reflects on its philosophical and religious implications. (“Where are we bound? Is it any different, in fact, from where we were going in the first place?”) Erdrich seems to be setting up questions that will later be answered, but soon after Cedar returns from visiting her birth parents, all of the dramatic uncertainty that Erdrich has so deftly accumulated funnels suddenly into a blunt, action-packed plot: the government calls for a state of emergency, broadens the Patriot Act, and begins detaining pregnant women in prisons to monitor any fetal abnormalities (allegedly the state keeps the successfully birthed babies).

The father of Cedar’s unborn child, Phil, comes to live with her. Soon after, officers break into her house and she wakes up in a hospital. In one passage, Cedar looks out the window and we momentarily return to the eeriness of the novel’s first half:

Beyond us, trees and more bunches of trees glowing in fall colors all along the river…. The thing is, I don’t think the leaves had changed yet when I was captured.

But this oddity immediately receives a rational explanation: “Come to think of it they must be giving me drugs.”

The rest of the novel is taken up with Cedar’s escape, aspects of which resemble a spy thriller: Cedar and her hospital roommate, Tia, unravel their blankets in order to make a rope; Eddy gives Cedar a portion of his diary with an encoded message; Sera writes escape guidelines on rice paper so that Cedar can eat them afterward; when they climb out of the window, Cedar and Tia set up a tape recorder that will “start responding to anybody trying to open the door, so that nobody thinks we’re gone yet.”

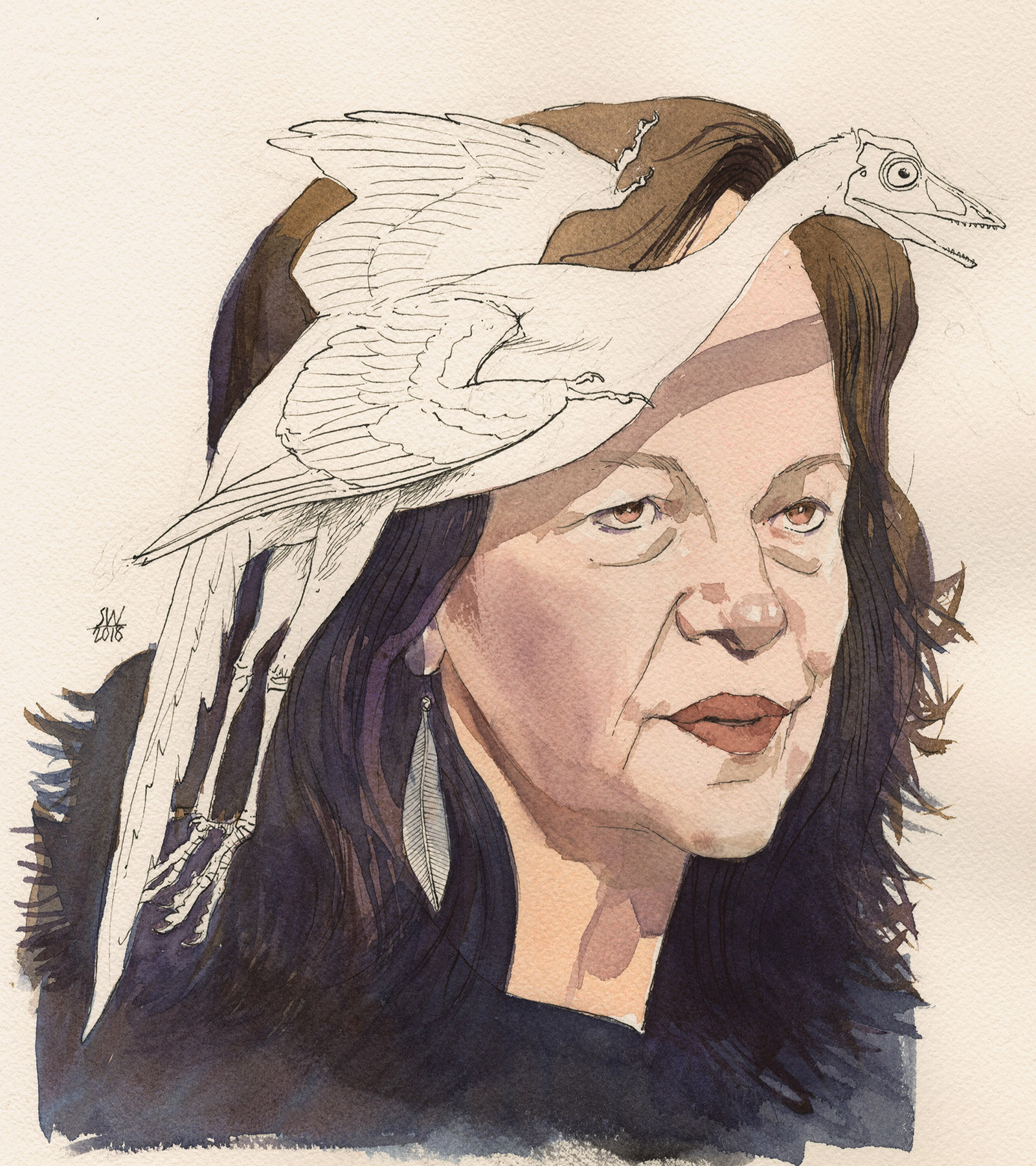

While Erdich’s narratives are often suspenseful, the action in Future Home falls somewhat flat, unsupported by the elegance and subtlety that characterize her previous works. Cedar witnesses two pieces of concrete evidence of evolution’s regression: an archaeopteryx (the ancient transitional species between dinosaurs and modern birds) and a “saber-toothy cat thing” that eats a chocolate Labrador. It strains credulity, even on the book’s own terms, that a biological phenomenon that has so recently been observed in “small-celled creatures and plants” would manifest immediately in these large prehistorical beasts. The response of the government is similarly implausible. In addition to strengthening the Patriot Act, practically overnight it becomes a theocracy, “the Church of the New Constitution,” and all of the streets are renamed after Bible verses.

Advertisement

These changes take place alongside various anomalies that predate the events of the book: winter is already a “ghost season”; the northern and southern borders of the United States have been sealed off; translucent “Jellyfish” float around parks and yards collecting cell phone information for big corporations. In establishing the setting of her novel, Erdrich uses the permission of speculative fiction to imagine the future outcomes of early-twenty-first-century predicaments—global warming, surveillance, omnipotent corporations, nationalistic isolationism. The result is something like an uncontrolled experiment; when you add an unknown variable to an already unfamiliar set of conditions, it’s hard to keep track of what’s causing what and what comes first.

The book’s form—a diary intended to be read by others—further constrains the reader’s ability to understand the actual mechanisms and effects of evolution’s disruption and the government’s crackdown. We are restricted to the perspective of a single captive person who is kept uninformed. At one point, Cedar is told that “all of the prisoners in the country have disappeared. Most people say they have been euthanized…. The prisons are for women.” This development—which would (on the basis of the current prison population) amount to the mass execution of more than two million Americans—is passed over with unsettling speed. This is not to say that Cedar, or Erdrich, is uninterested in the plight of these millions, but rather that even enormous consequences of the novel’s conceit are subsumed by the necessarily narrow concerns of one persecuted woman and her unborn child.

The galley of Future Home of the Living God included a note from the author, left out of the finished edition, in which Erdrich says explicitly that the idea of genetic backwardness was inspired by her sense of things moving backward politically:

In 2002, a year after I had given birth to my youngest daughter, the false intelligence leading to the war in Iraq was being assembled and President George W. Bush had signed what is known as the global gag rule. Regressive times. I started wondering why evolution started and what would happen if, just as mysteriously, it stopped.

She set the manuscript aside until the 2016 election, when things had “circled back to 2002, only worse”—she specifically cites the new global gag rule, which “cruelly cuts off US funds from international family planning [and] eliminate[s] HIV testing, Zika testing, and birth control.” So the halting and reversal of genetic evolution stand in for what Erdrich sees as the halting and reversal of political progressivism. The sabertooth cat in Cedar’s backyard is, like the swastikas in Charlottesville, something we never thought we’d see again, a symptom of a widespread backwardness.

The explicitly allegorical motivation behind Erdrich’s premise goes some way toward explaining the looseness with which she sees it through; realistic physical manifestations are less essential to the novel’s project than the sheer concept that “our world is running backward.” The impossible sabertooth cat and archaeopteryx should, then, be understood not as the most likely products of Erdrich’s posited genetic mutation but as representations of an idea. They have this in common with animals in her other works (the folkloric buffalo to whom the eponymous Round House is dedicated, for instance).

Yet the allegory is circular: evolution’s symbolic reversal both stands in for and results in the same thing. The limitation of women’s access to reproductive health care, which Erdrich rightly views as a turning back of social and political progress, is symbolized by the genetic reversal of evolution (the turning back of biological progress), which, in turn, results in the novel in the limitation of women’s reproductive rights. The allegory does not help us better understand the problem it represents; it brings us back to where we started.

Perhaps the biggest source of disappointment in Future Home of the Living God is that Erdrich’s conceit constrains one of her greatest literary strengths: her acute sensitivity to the randomness of human existence. In The Round House, the protagonist’s father tells a story about the local priest, Father Travis Wozniak, who had been in Dealey Plaza in Dallas on the day of John F. Kennedy’s assassination. According to Travis, shortly before the motorcycle escorts drove up, a dog “ran out into the middle of the street and was quickly recalled by its owner”:

It often bothered Travis afterward to think that if only the dog had got loose at another time, perhaps just as the motorcade passed, messing up the precision and timing of things, or if it had thrown itself under the wheels of the presidential convertible in an act of sacrifice, or leapt into the President’s lap, what followed might not have happened. This so gnawed at him on some nights that he lay awake wondering just how many unknown and similarly inconsequential accidents and bits of happenstance were at this moment occurring or failing to occur in order to ensure he took his next breath, and the next. It gave him the sensation that he was tottering on the tip of a flagpole. He was poised on circumstance.

Occasionally Erdrich’s preoccupation with chance events reaches almost supernatural extremes, as in Tales of Burning Love (1996), in which a trapeze act is interrupted by a bolt of lightning that strikes at the exact moment that the two gymnasts are suspended in the air, killing one of them but not the other. The one that survives is the mother of a character in the novel. This same character, who owes her existence to exceptionally random good fortune, speculates on the development of consciousness: “Of course it could be a mistake—consciousness that is…. A mistake of natural selection, a glitch, a dead-end mutation.” Maybe all of us, all of culture, all of human history, are the products of an incidental glitch.

In Future Home of the Living God, Erdrich leaves little room for the idiosyncratic interference of chance. Cedar’s story is overdetermined. Once the government gets involved, there is only one way for it to end: in captivity. This can be seen as a warning—a demonstration of the government’s power and willingness to deny its citizens their right to fully and fearlessly live out their unpredictable and meaningful lives. As a member of a persecuted minority herself, Erdrich is familiar with this dangerous reality. But it is unfortunate that this warning about the government’s restrictive force results in the restriction of the novel’s own narrative possibilities. The strongest features of Future Home of the Living God—the vibrant Potts clan, Cedar’s relationship to her birth and Native identity, her growing bond with the strange fetus inside of her—are not so much enhanced as eclipsed by an apocalyptic idea whose effectiveness is primarily symbolic.

Even Erdrich’s keen impressions of her characters’ experiences get muffled by her premise. Ordinary grievances are presented as casualties of the world’s biological demise. In one scene, Cedar sits with Glen and Sera in the backyard:

The deep orange-gold of the sun is pure nostalgia. An antique radiance already sheds itself upon this beautiful life we share. I grow heavy, rooted in my lawn chair. Everything I say and everything my parents say, the drift of friends, the tang of lemonade, the wine on their tongues, the cries of sleepy birds and the squirrels launching themselves…all of this is terminal. There will never be another August on earth, not like this one.

This striking description of the nostalgia brought on by setting suns in August is cast as a tragic consequence of the world’s end, but all gorgeous evenings spent with aging parents tend to make one feel an impending sense of things ending. Elsewhere, Cedar says:

I want to see past my lifetime, past yours, into exactly what the paleontologist says will not exist: the narrative. I want to see the story. More than anything, I am frustrated by the fact that I’ll never know how things turn out.

But no one ever knows how things turn out, and not because of climate change or earthly catastrophes but because we rarely live long enough to see our children grow old, because we can never reach outside our own narrow perspectives, because we can never anticipate all of the “inconsequential accidents and bits of happenstance” that will affect the course of our lives and histories. The failing earth here becomes a scapegoat for the tragedy of the human condition.

This Issue

April 5, 2018

Bang for the Buck

Beware the Big Five

As If!