The story begins late on Christmas Eve, 2012. Édouard is twenty years old, and he has left the apartment of friends in northeast Paris, where they have had a few bottles of wine. He takes a share-bike as far as the place de la République, and then, to clear his head, he decides to walk the rest of the way to his little studio near the Canal Saint-Martin. In the large square, under reconstruction at the time, a man about a decade older tries to pick him up. Édouard resists at first, and then takes the man, Reda, home with him. They have sex five or six times over the next few hours, nap, shower. When Reda starts to leave, Édouard notices that his phone and iPad are missing. He accuses Reda in the gentlest way, and desire turns to ferocious violence: Reda strangles him with a scarf, pulls out a gun, and rapes him.

Except the story does not begin on Christmas Eve, 2012. It begins more than a decade earlier, when Édouard lived in the poorer north of France, and still went by his given name of Eddy. Endlessly bullied by classmates for his effeminate gestures, mocked by his brawler father, Eddy escapes only thanks to France’s elite education system, mastering the social codes that will bring him all the way to Paris, where he has remade himself as a bourgeois. Or the story begins decades earlier than that, in French Algeria, where Eddy’s grandfather fought, and from which Reda’s father migrated to Paris. The etiology of the crime, and the punishment that may follow, stretch past the experiences of two men in the 10th arrondissement. And the walls of the little studio apartment in which Édouard could have lost his life expand to encompass entire regimes of public and private cruelty.

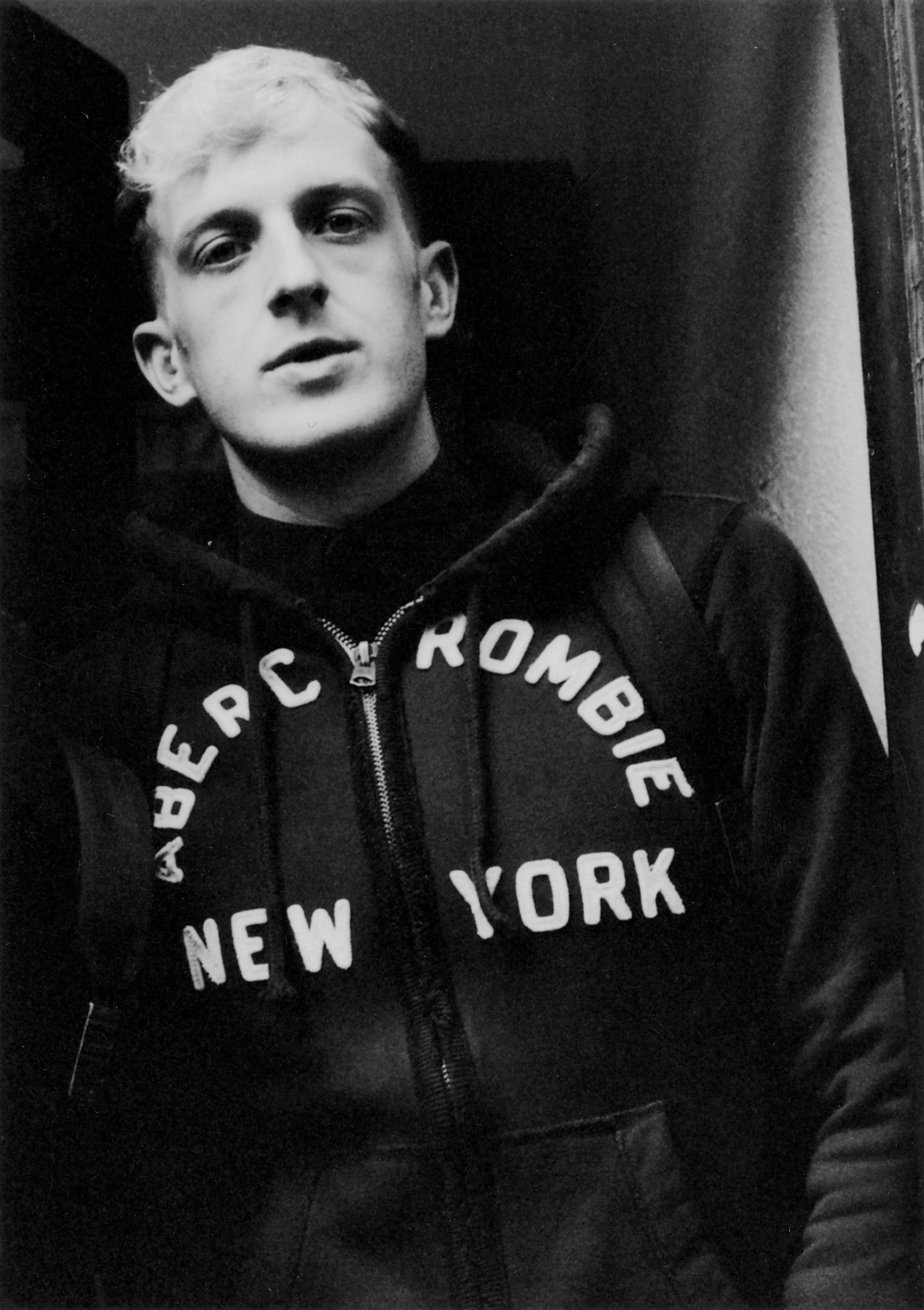

“Édouard” and “Eddy” are both Édouard Louis, and the savagery of that night spirals back and branches forward in History of Violence, his second autobiographical novel. It’s a treatise on class, race, and sexuality intertwined with an agonizing testimony of crime, recounted in a prismatic fashion that fractures those horrible minutes of Christmas 2012 into shadows and reflections. Since its publication in France in 2016—where it drew both raves and furious denunciations—History of Violence has become an international success; last year it was adapted for the stage by Thomas Ostermeier of the Schaubühne, one of Berlin’s leading theaters. It also afforded its author a public renown that he has eagerly embraced, with aims that go well beyond literature.

Louis has since emerged as the French literary world’s most implacable, immoderate opponent of Emmanuel Macron, the young president whose promises of national renewal have lately run aground. Having endorsed the far-left anti-European candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the 2017 presidential election, Louis has gone on to flay Macron as “ultra-violent” and as “someone who hates poor people,” and to insist that Macron and indeed the entire political class have “blood on their hands.” When a report appeared that Élysée officials had taken an interest in Who Killed My Father, a polemical tract Louis published last May, he rose up in fury. “I write to shame you,” he wrote on Twitter to @EmmanuelMacron—a “J’Accuse…!” that fit into 280 characters.

Who Killed My Father is a short pamphlet of fewer than a hundred pages, with none of the precision or seriousness of his two novels. It was released in France when a majority of the country still supported Macron, but arrives in English as the president’s approval ratings have sunk to the same abysmal level that limited his two predecessors to a single term in office—and as he has become the object of hatred for a small, furiously angry movement of working-class French people. Louis has enthusiastically embraced the gilets jaunes, and in the English-speaking world Who Killed My Father looks destined to become a vindication of these anti-Macron protests, whose participants live largely outside the capital and whose average incomes hover just above the poverty line. For Louis is the boy who escaped the boondocks yet became its spokesman. He is a passionate writer, and outspoken on behalf of minorities in a country that pretends they don’t exist; he is also impetuous, self-regarding, and—at a moment of alarming crisis in France and across Europe—all too willing to support populist reaction over sincere political engagement.

Louis was born Eddy Bellegueule in 1992 in Hallencourt, a village in the northern region of Picardy. (The nearest city is Amiens, Macron’s hometown.) His brutal, poverty-stricken childhood and the intense homophobia of his family and schoolmates were the subject of his first book, The End of Eddy, which became an unexpected best seller in 2014. “From my childhood I have no happy memories,” it begins, and its plainspoken pages recount a youth marked by abject privation, spit-hocking bullies, rampant alcoholism, and newborn kittens pounded to death in plastic bags. It’s a hard-knock life, though Eddy does not fully wish to escape it; when he wins his admission to the lycée in Amiens, where he studies theater, he feels at once that he’s escaped a nightmare and betrayed his family. Louis, having moved to Paris and renamed himself, published The End of Eddy while a student at the École Normale Supérieure, the grande école of France’s most rarefied elite.

Advertisement

Two older writers, also northerners who came to the capital, hovered over The End of Eddy and continue to shape the aims of Louis’s literary disclosures. One is Annie Ernaux, who has spent decades exploring the psychological price of class distinction in such autobiographical works as A Man’s Place (1983) and The Years (2008). The other, to whom The End of Eddy is dedicated, is Didier Eribon, a sociologist working in the tradition of Pierre Bourdieu, whose marvelous book Returning to Reims (2009) plumbs his dissociation from both his working-class roots and his new bourgeois life. Like Louis, Eribon distanced himself from his family through the French education system, writing a biography of Michel Foucault and becoming a professor in Amiens, where he and Louis met. Eribon’s family were reliable left-wing voters in the past but now, like Louis’s, support Marine Le Pen.1

Even more than The End of Eddy, History of Violence is indebted to Eribon: it is a book that puts sociology in the service of autobiography. And Eribon, or “Didier,” is a character in it. It’s his apartment that Édouard is leaving on the night of December 24, toting two books Didier gave him as Christmas gifts (like a cocky normalien he drops the authors’ names, Nietzsche and Claude Simon) when Reda chats him up in the place de la République. “I wanted to take his breath in my fingers and spread it all over my face,” Édouard remembers. He tells us of his curiosity about Reda, of “when we were lying together in bed and I was begging to know more about him, about his life,” but in fact we learn very little.

Reda is Algerian, of Kabyle ethnicity. He does odd jobs as a plumber, or so he says. We get tiny reflections of his body and hints of who he might be through mirror images of the narrator’s past—Édouard imagines Reda goofing off in school as his own cousin did, and if Reda has stolen his phone and iPad, well, Eddy Bellegueule stole in his youth as well.

Our only real glimpse into Reda’s inner life comes from a long description of the suffering endured by his father in the early 1960s, at the end of the Algerian war. His father, Reda tells Édouard, lived in a Paris banlieue in a squalid factory hostel, managed by a “violent and tyrannical” veteran who thought his service in the former colonies meant he could “understand the psychology of the immigrants.” In the hostel, the immigrants slept in tiny rooms subdivided with plywood, and “their misery comes out in [the] noise” of creaking beds and scream-eliciting nightmares. What little the novel provides to fill in the cipher of Reda, beyond the “Arab male” designation in Édouard’s police report, comes from this colonial legacy, passed from father to son.

Yet Louis makes hardly any effort in History of Violence to examine the psychic or emotional consequences of colonialism, whose effect on Reda he describes principally in terms of social categories, social privileges, social disadvantages, and social stereotypes. There’s nothing wrong with this; Stendhal, Balzac, and Zola all used the novel to paint society in broad strokes. Louis, though, uses sociology as a narrative tool, in ways that flatten much more than they illuminate. (Even the book’s title has the sound of a definitive academic statement, rather than a memoir of a particular trauma.) Consider this passage on higher education, which Édouard describes as

pretty much the only way I could get away from my past, not just geographically, but symbolically, socially—that is, completely. I could have gone to work in a factory like my brother, three hundred kilometers from my parents, and never seen them again; that would have been a partial escape. My uncles, my brothers would still have lived inside me: I’d have had their vocabulary, their expressions, I’d have eaten the same things, worn the same clothes.

Louis wants us to know that all lives are “symbolically, socially” conditioned, that the life of a factory worker in Picardy will differ from one in Alsace or Brittany only in superficial ways. The outward manifestations of individuality are but excrescences of a social order whose disadvantages most cannot escape. And if tastes, actions, and beliefs are wholly socially determined, that extends even to the author’s own rape, which Louis casts as just one act of violence in a cascade of aggression extending back to Reda’s father’s suffering in the banlieue, and before that to colonization and war in Algeria. Though Édouard recounts the moments of his rape with unflinching detail, the book avoids all the therapeutic strains in American writing on sexual assault and asks instead whether someone who’s forced to “endure what you never wanted to endure” can and should understand the social roots of his attacker’s wrongdoing—and thus refuse to advocate for his punishment.

Advertisement

The debate over the degree to which a criminal is responsible for his actions, and to which societal disadvantages can diminish one’s personal guilt, is a staple of a hundred Law and Order episodes; and in France, too, left-wing appeals to social explanations of crime face off against a right-wing insistence that individuals must be held to account. (Nicolas Sarkozy won the French presidency in 2007 on exactly this tough-on-crime, no-social-excuses platform.) But Louis stacks the deck in favor of social determinism by reducing his characters to cutouts that closely resemble right-wing stereotypes—whom we are then obliged to give the benefit of the doubt. The short-tempered North African criminal and the poor, hard-drinking northerners must be the way they are for unjust reasons; otherwise they would be racist or classist caricatures, and that couldn’t possibly be the case in the book we’re reading.

The exception, of course, is Édouard, the only fully developed character. It’s Édouard who surprises Reda by speaking a few words of Kabylian, a language he studied; it’s Édouard who gets to express his plural identities in the bourgeois and working-class worlds; and it’s Édouard, above all, who gets to correct the assumptions and misprisions of a justice system that reduces Reda to an “Arab male” and himself to the victim. “They want to lock you up inside a story that’s not your own,” Édouard says at one point. But if History of Violence attempts to reclaim Reda’s story from the justice system that has taken it from him, Louis declines to afford such individuality to others; their role, like the players in a Brecht Lehrstück, is only to illustrate the workings of violence at a societal scale.

History of Violence is a novel. And yet, as the author told the French booksellers’ magazine Livres Hebdo upon its release, “In this book, there is not a single line of fiction.” While earlier generations of gay writers, from André Gide and Jean Genet to Edmund White and Hervé Guibert, drew on their own emotional and romantic experiences to animate their fiction, Louis’s first two books are closer to the recent nonfiction novels of Karl Ove Knausgaard, Sheila Heti, or even Chris Kraus—novels that are shot through with the feel of memoir and claim increased moral consideration by being “based on a true story.”

Louis’s alleged attacker, Reda (or Riadh; like Louis, he has used multiple names), has always denied raping him, although he has admitted to stealing his iPad. He had already served almost a year in prison for an unrelated crime, and he was arrested a few days after the publication of History of Violence for cannabis possession. Subsequently he was indicted for the attack on Louis, and as of March 2019 the case is ongoing; the judge has reduced the charges from rape to sexual assault, and she has stated that, regardless of Reda’s objections, Louis’s accusations are supported by both medical evidence and witness testimony. (The novel has not been entered into evidence.) Louis has refused all judicial summonses, and now he wishes—despite having pressed charges hours after his attack—that the case would be thrown out. “I cannot bear the thought,” he says, “that my story has been used to imprison anyone.”

In History of Violence, too, Édouard hates the thought of imprisoning Reda. He at first refuses his friends’ entreaties to go to the police, and later finds himself so disgusted by cops’ racism that he wishes he had never reported the crime. More than Reda or the northerners, the truly stereotypical characters in History of Violence are the police officers, who cast doubt on his testimony, have never heard of gay cruising, can’t understand that Reda is not Arab but Kabyle. (The most famous person in France, the soccer star Zinedine Zidane, is Kabyle.) Louis describes the police as not only racist but also stupid and fat:

I can hear the compulsive racism that, in the end, seemed the crucial bond between them, the only bond they had—apart from their too-tight uniforms—the only glue that held them together, because for them Arab didn’t refer to somebody’s geographical origins, it meant scum, criminal, thug.

What elevates History of Violence beyond the limits of its social determinism is the marvelous structure of its narration. It is style, much more than characterization, that gives the novel its moral and political force. “Tell it in the order that it happened,” one police officer tells Édouard, but Louis does nothing of the sort. The novel begins after the crime, back in Picardy, where Édouard is staying with his sister Clara. We jump from there back to the morning after the rape, then forward to the police station, then months into the future. Édouard and Reda meet on page 45 but don’t get to the apartment until page 80. The novel’s climax is not the rape, which occurs about halfway through, but rather the argument over whether to go to the police. Fracturing the account this way does more than a hundred Bourdieu-parroting apothegms to establish the social stakes of the novel, and to demonstrate how violence stretches past the personal.

Much of this comes to us not through Édouard’s first-person narration but through quotations from Clara, whom Édouard eavesdrops on back in Picardy, “hidden on the other side of the door” while she recounts the crime to her husband, “her voice compounded, as always, of fury, resentment, irony too, and resignation.” It is not only that: Clara speaks in a demotic, regional French that flouts grammatical rules and brims with class markers. Far more than The End of Eddy, this book uses popular speech as a compositional tool; Édouard’s Christmas nightmare returns to him, and comes to us for the first time, in the French he abandoned along with his given name. Indeed, Louis often interrupts Clara’s working-class French with italicized asides in Édouard’s more formal language, the better to underscore their social distance.

This grinding between registers of French is the crucial trick of History of Violence. Hundreds of Clara’s sentences use a common colloquial form in which the subject of the sentence is followed by a redundant pronoun—for example, Reda il criait, literally “Reda he was shouting.” (This grammatical tic is called, in a coincidence some of Louis’s political opponents might appreciate, dislocation à gauche.) She uses nonstandard contractions like t’es or t’aurais, she uses the highly conversational quoi for emphasis, and she uses regional, lower-class pronunciations that Louis renders with misspellings (pis instead of puis, “then”). Multiple sentences are run together with commas or with no punctuation at all. As for Édouard’s own speech, more polished, more Parisian, Clara describes it as sounding “like some kind of politician” (“son vocabulaire de ministre”). Their father, in The End of Eddy, thought of such correct French as the language of “faggots.”

I found Louis’s rendering of Clara’s French winning in many places, hammy and overdrawn in a few. But the distinct linguistic registers disappear in Lorin Stein’s English translation, which makes almost no effort to reproduce them. A sentence of Clara’s like “L’usine elle embauche plus,” with both a redundant pronoun and a nonstandard negative, appears in English as the stiffly correct “They’ve stopped hiring at the factory.” “J’ai rien dit moi” becomes “I just kept my mouth shut.” Clara’s tumbling, unpunctuated run-on sentences get chopped up into bite-size morsels; conversational repetitions are omitted; colloquial ça’s and quoi’s get vaporized. All this makes the dozens of pages in which Clara, not Édouard, recounts what happened that Christmas Eve—at a personal, social, and linguistic remove—tonally indistinguishable from Édouard’s narration.

If Stein has smoothed out Clara’s demotic French, he has coarsened the book’s tone in other ways. “Fuck” is deployed liberally, and every sexe becomes a “cock,” even in the midst of rape. In Stein’s most inexplicable choice, he has rendered a repeated line of Reda’s with a crude gay sentiment it lacks in the original, and one that sullies the novel’s engagement with violence and society. Over and over, as he prepares to rape Édouard, Reda threatens, “Je vais te faire la gueule”—gueule is a colloquial word for “face,” and it is also half of Louis’s real last name. A fair translation would be “I’m going to beat your face in,” or, less literally, “I’m going to fuck you up.” In Stein’s rendering, however, Reda’s threat becomes: “I’m going to take care of your ass.” This is a lacerating mistake, and grafts base sexual desire onto a crime motivated by humiliation and vengeance. (The men, after all, had already had consensual sex all night.)

Stein is certainly no homophobe; that much is clear from the sensitivity he brings to the expressions of gay desire elsewhere here, including a moving passage in which Édouard, only hours after his attack, nearly begs a friend to make love to him “so that Reda wouldn’t be the last person this has happened with.” He also produced an excellent translation of La meilleure part des hommes (2008), a novel of AIDS and gay separatism by the (straight) French novelist Tristan Garcia. I am at a loss to explain this distortion, which I must assume the author, a fluent English speaker, approved of.

Louis was riding high last summer. History of Violence had come out in English and its theatrical adaptation was on stage in Berlin; he was holding court at Harvard at a seminar billed as “The New French Intellectuals”; he was on the cover of Les Inrockuptibles and the magazine of Le Monde. And he had a new book to promote: Who Killed My Father, whisper-thin but thick with fury. Unlike his first two, this one does not present itself as a novel; it’s a political pamphlet in the form of a vindication of the father he left behind. This may surprise those who remember the father’s portrait in The End of Eddy as, like almost everyone in that book, a violent, alcoholic, racist homophobe who supported the far right. He was someone whose very name Louis wanted, as the original French title had it, to “have done with”—his new name is in partial tribute to his substitute father figure, Didier Louis Eribon. In this new book the son eulogizes his real dad as both father and martyr, and then pivots at the end into an enraged, even hysterical denunciation of the entire French political class. In The End of Eddy Louis undertook a symbolic assassination of his family; in Who Killed My Father, the devastation is more corporeal, and the attackers don’t know or care what they’ve done. (Louis’s father is not dead. Upon the book’s release he was only fifty.)

“When I went out at night and met men in bars,” Louis writes,

and they’d ask how I got along with my family—it’s an odd question, but they ask it—I would always tell them I hated my father. It wasn’t true. I knew I loved you, but I felt a need to tell other people that I hated you. Why?

The End of Eddy offered a few reasons: regularly calling his son a “pussy,” for one. But now we meet the father who puts gifts under the Christmas tree even when money is tight, who shares sweets with his son at the local bakery, who sings Céline Dion songs “at the top of your lungs” in the family car. “It often seems to me,” Louis writes, “that I love you.”

The haters have other names. Louis’s father suffered a terrible accident at work; initially he qualified for disability benefits, but later he was forced to take menial part-time jobs far from home after Sarkozy’s government replaced traditional unemployment benefits with a workfare scheme. Sarkozy was “breaking your back,” Louis writes, as his father stooped to pick up trash, and soon François Hollande “asphyxiated you” with further labor reforms; as for Macron, he “is taking the bread out of your mouth” through a withdrawal of housing subsidies. Sarkozy, Hollande, Macron; right, left, center: all of them stand accused of violence, even of murder. “I want to inscribe their names in history, as revenge.” (Stein has translated this book too, with no troubles.)

Eribon’s Returning to Reims meticulously and movingly analyzed the political and social distance between a gay son and the parent whose social milieu he has left. Who Killed My Father jabbers and slashes, and its discussions of the laws that have “killed” Louis’s father could fit into a couple of tweets. These politicians, he now avers, are not just executioners; they are also directly responsible for the horror show that coursed through The End of Eddy, and their monstrousness offers his family an absolution from the racism, sexism, and homophobia he recounted and escaped. “If my father is racist,” Louis told James McAuley of The Washington Post upon the book’s release, “it’s the fault of Emmanuel Macron, the fault of François Hollande, the fault of Manuel Valls [Hollande’s right-leaning prime minister], the fault of Sarkozy.”

The social determinism of History of Violence has hardened into dogma now, and in Who Killed My Father Louis takes it to extremes. “The world was responsible” for his grandfather’s alcoholism. At one point Louis actually writes the equation “Hatred of homosexuality = poverty,” which suggests he has not spent much time with France’s old traditional right. If he really believes that tolerance is the natural manner of society and hatred only a consequence of the dominance of elites, all I can conclude is that he never got around to reading the Nietzsche volume Eribon gave him that fateful Christmas Eve.

Between its publication in French and its arrival in English, though, this book has taken on a new relevance thanks to the gilets jaunes movement, whom Louis has marched with and defended on air and in print.2 The movement’s intense personal hatred of Macron surely appealed to him, and in interviews he has suggested that its anti-environmentalism and intolerance were just venial sins that could be expunged if the left got involved. Whatever their demands, democratic or authoritarian, the rage of the gilets jaunes was its own justification, and those who bridled at the right-wing elements within it were, in Louis’s view, just out to silence the people who brought provincial misery to Paris, people who resembled his own father (though most of them are middle to lower middle class rather than below the poverty line). On December 4, a few days before the most violent episodes of the movement, Louis thundered in a long Twitter thread: “When the ruling classes and certain media outlets speak about homophobia and racism among the gilets jaunes, they aren’t really talking about homophobia or racism. They are saying, ‘Shut up, poor people!’”

Certainly some in the French media have cited the racism, homophobia, and anti-Semitism of the gilets jaunes to delegitimize their call for institutional change. But observing this in bad faith does not mean it’s false, and Louis’s support for the gilets jaunes exhibits the same flattening social determinism he brings to History of Violence, a flattening now so extreme that it permits a gay left-wing militant to march alongside Holocaust deniers, not to mention flagrant homophobes.

Something similar happens at the end of Who Killed My Father, after Louis names and shames the establishment politicians who have rent his father’s body and stamped on his dignity. “You’re right,” responds his father, “what we need is a revolution.” But what kind of revolution would that be? Marine Le Pen—the top vote-getter among the future gilets jaunes, twice as many of whom voted for her as for Mélenchon—promised a revolution during the 2017 election, and after she made the second round Louis wrote in The New York Times that his father had surely voted for her. Louis “imagined him bursting with joy in front of the TV” when she made the runoff, “the same joy he felt in 2002 when Jean-Marie Le Pen…also made it to the second round. I remembered my father shouting, ‘We’re going to win!’ with tears in his eyes.”

Louis is only twenty-six. He has time enough to step back from the sudden fame centered on his own autobiography and to formulate a politics that treats racism and homophobia, not to mention rape and attempted murder, as more than epiphenomena. Louis thinks it’s an act of justice to exculpate his father (and his rapist) through their social circumstances, but his totalizing view of power denies his subjects any true agency or inner life, and precludes a full reckoning with the humanity of those Louis would have us treat as more than stereotypes.

One way to afford others this full recognition is through literature, “a mirror carried along the high road” that, Stendhal wrote, always also reflects the mire at our feet, but so far the only three-dimensional Frenchman in Louis’s novels is “Édouard.” It is selfish, and not very solidaire, to treat people this way, as if their loves, their hatreds, their whole lives have no deeper roots than economics. Denying human fullness to those you write about is also a kind of violence.

-

1

Louis included both Ernaux and Eribon in his first book, an edited collection of essays on Pierre Bourdieu. A new edition of Returning to Reims, with an introduction by Louis, was published in France last year. ↩

-

2

See James McAuley, “Low Visibility,” The New York Review, March 21, 2019. ↩