Other colossi crumble or are dragged off their pedestals by angry students and dismissive dons, or you don’t notice them anymore because they are so sadly weathered. But Winston Churchill is still up there, if anything more firmly anchored as the years go by, glaring out at posterity with unquenched pugnacity.

This miraculous preservation has not been an entirely natural process. Churchill laid the foundations of his own monument: five volumes on the Great War, then another six volumes on World War II, making good on his threat to the House of Commons in 1948 that it was “much better…to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.” He confided to William Deakin, one of the many brilliant research assistants he plucked from academe, “This is not history, this is my case.”

By and large, the case still stands. Even the more thoughtful critiques, such as Robert Rhodes James’s Churchill: A Study in Failure 1900–1939 (1970) and John Charmley’s Churchill: The End of Glory (1993), have not left much of a dent. Any cracks in the façade were sedulously repaired by the eight-volume official biography (1966–1988), the first two volumes by Churchill’s son, Randolph, the remainder by Sir Martin Gilbert, which is simultaneously scrupulous, awestruck, and forgiving.

Now comes Andrew Roberts’s Churchill: Walking with Destiny. No biographer could have a more intimate, even sensuous grasp of the whole Churchillian milieu, from his birth in Blenheim Palace to his state funeral in St. Paul’s ninety years later. Roberts intends the book as an ultimate act of homage, but the material is so abundant and so candidly presented that you can come away, certainly from the first five hundred pages, with rather different conclusions from his. Only rarely do we find him glossing over or omitting examples of Churchill’s brutish and vindictive side.

The book is necessarily huge, with a narrative that skims along yet has the self-confidence to dally on every endearing detail: the old music-hall songs that Churchill sings, tunelessly, at moments of stress, his velvet boiler suits and square-crowned bowler hats, his intense application to duty while giving the impression that he was always doing exactly what he wanted, his long and mostly happy marriage to a wife he didn’t go on holiday with, the four children whom he adored, three of whom came to sad ends, his insatiable money-grubbing, his inexhaustible delight in each new pastime—polo, fencing, butterfly-collecting, painting, flying aircraft (often over the Channel in wartime, though never a fully qualified pilot as far as I can see), foxhunting, poetry, which he learned large chunks of, despite his patchy education.

One of Roberts’s great merits is his readiness to quote long passages from Churchill’s speeches and letters to bring home his ever-springing vivacity, his ability to switch from soaring Augustan flights and archaic language to plain prose and earthy slang. Nothing, too, can convey better the sheer awfulness of his childhood than to read the horrible letters his parents wrote to him at boarding school. In material terms, he was spoiled all his life. He was heir to the dukedom of Marlborough for a couple of years after his father died. He never boiled an egg; he rarely went anywhere without a valet, even to the battlefields of the Boer War and Flanders. But emotionally, he was starved into greatness.

Lord Randolph and his American wife, Jennie Jerome, were faithless and feckless darlings of late-Victorian society. Her father, Leonard Jerome, was hugely rich. But the Randolph Churchills were always short of cash. Jennie had plenty of time for her numerous lovers, but she seldom bothered to visit Winston at school, though he never stopped craving her affection. After her death, he poignantly wrote of her, “She shone for me like the evening star. I loved her dearly, but at a distance.”

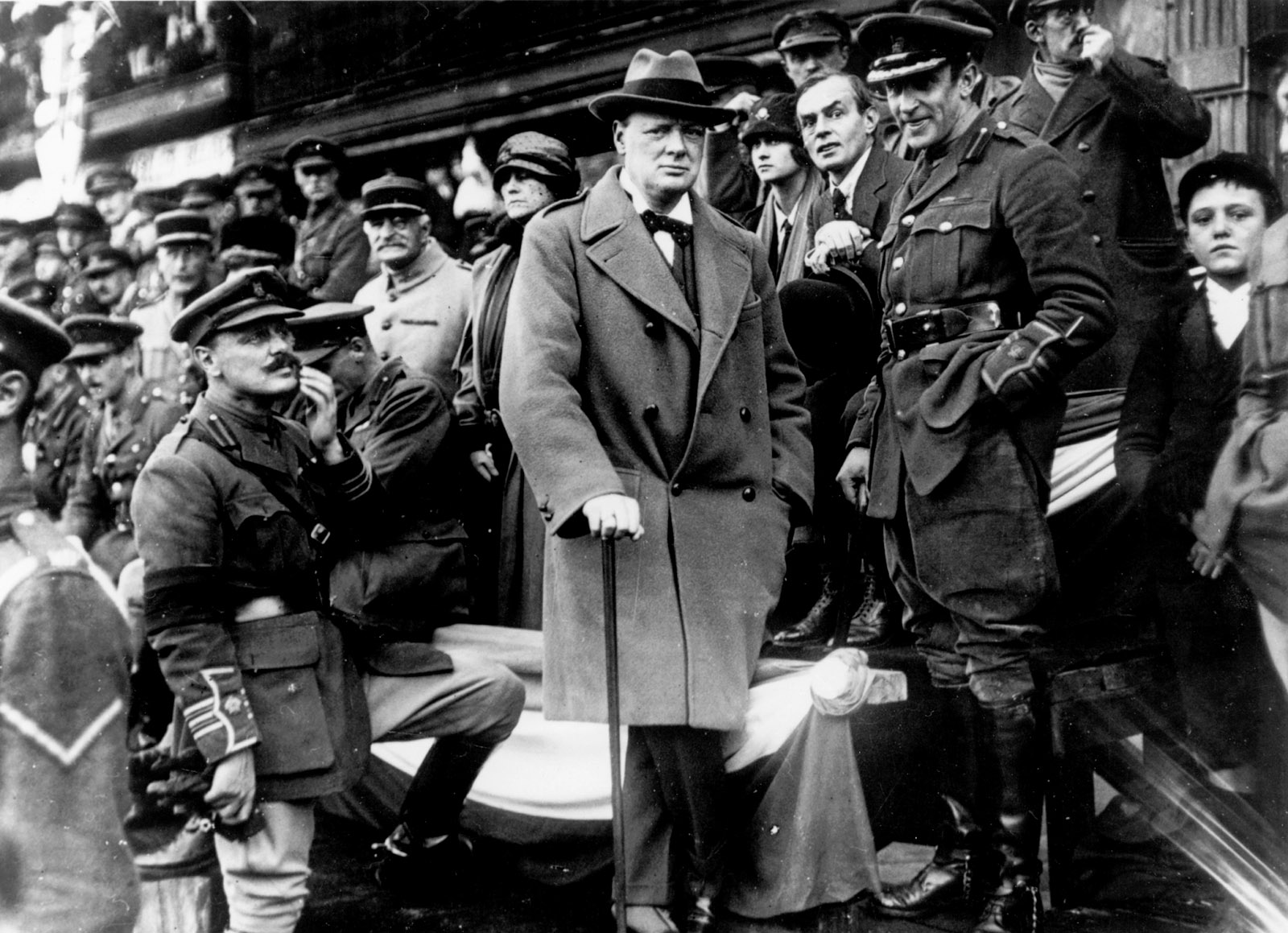

“Few have set out with more cold-blooded deliberation to become first a hero and then a Great Man,” Roberts declares. Churchill was not the first man to seek fame in small wars abroad in order to parachute into politics at home, but few successful politicians can have enjoyed soldiering quite as much as he did. He scoured the globe to find a shooting war he could be in on, either as correspondent or combatant: Cuba first, then the North-West Frontier of India, the Sudan, and finally the Boer War.

The reports and books he wrote out of these dubious adventures still have the tingle of a frosty dawn. The Malakand Field Force of September 1897 was a typical punitive expedition on the North-West Frontier to burn the tribesmen’s villages and crops, chop down their orchards, fill up their wells, and destroy their reservoirs. “Financially it is ruinous. Morally it is wicked,” he told his mother, “but we can’t pull up now.” Afterward he wrote, “It was all very exciting and, for those who did not get killed or hurt, very jolly.” The next year, at the Battle of Omdurman against the Dervishes of the Sudan, he took part in the last great cavalry charge: “Talk of Fun! Where will you beat this?” he wrote later.

Advertisement

Churchill did speak of war as cruel and barbarous, but like Charles de Gaulle, he thought of it as a normal and even socially progressive part of life. At the end of 1917, after the most frightful slaughter in human history, he told the poet Siegfried Sassoon that “the present war…had brought about inventive discoveries which would ameliorate the condition of Mankind”—in sanitation, for example. Twenty years later, he still thought the same. He told his private secretary in October 1940, “A lot of people talked a lot of nonsense when they said wars never settled anything; nothing in history was ever settled except by wars.”

All his life, he was a convinced imperialist. He stubbornly continued to believe that the Indians could never govern themselves or form a lasting nation, long after all but the blockheaded diehards had abandoned the cause. Roberts offers a careful but only half-convincing defense of Churchill’s involvement, or lack of it, in the relief of the terrible Bengal famine of 1943–1944, in which millions died. The anguished pleas from the incoming viceroy, General Wavell, still leave one with the feeling that someone who cared more for the Indians than Churchill did would have done more.

Roberts is a little indulgent, too, toward Churchill’s flirtation with eugenics, on the grounds that so many of his respectable contemporaries also fell for this noxious fad. But Social Darwinism remained a nasty miasma in his mind. Giving evidence in March 1937 to the Peel Commission, which was investigating unrest in Palestine, he declared unashamedly:

I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to those people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, or, at any rate, a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.

Accordingly, the Jews had the right to take over the whole of Palestine, a view from which he never retreated. He was a violent and persistent Islamophobe.

In some ways Churchill was deaf to the future, in others brilliantly prescient. In his second speech to the Commons, on May 13, 1901, he electrified the House with his prophecy that “a European war could only end in the ruin of the vanquished and the scarcely less fatal commercial dislocation and exhaustion of the conquerors.” He had made six drafts of this speech and then memorized it, which was to be his practice for the rest of his long career.

At that moment, he was opposing the plans of the secretary for war, St John Brodrick, to increase the size of the army by 50 percent. Churchill wanted the money to be spent instead on pensions and welfare. He was an enthusiastic ally of David Lloyd George in laying the foundations of the welfare state. In the same spirit, as prime minister, he led the wartime coalition in support of the Beveridge Report and the founding of the National Health Service. It was largely due to him that the postwar Conservative Party accepted and developed the welfare state that the Attlee government had claimed as its own after the war. If we were not so preoccupied with his glories as a war leader, we would recognize him more clearly as a crucial figure in the Liberal Conservative tradition of social reform.

But his bellicosity never lay quiet for long. By October 1910, he was talking of “the coming war with Germany.” No sooner had he become First Lord of the Admiralty the following year than he started preparing for one. He set up a Naval War Staff and embarked on a program of building new battleships with fifteen-inch guns, the largest caliber then afloat. He urged a program of building 60 percent more warships than Germany, arguing to Admiral Jacky Fisher in February 1912 that “nothing would more surely dishearten Germany than the certain proof that as a result of all her present and prospective efforts she will only be more hopelessly behindhand.”

Roberts declares that this early example of deterrence strategy “proved to be the correct one”—though just why he believes this is not made clear. He makes much of Churchill’s offer of “a naval holiday”—a promise not to build five super-dreadnoughts if Germany held back too. Churchill renewed this offer to the kaiser twice in 1913, but the kaiser rejected it as a publicity stunt. As a result, Churchill found himself leading an energetic arms race that continued right up to the final hours in the summer of 1914 when he mobilized the fleet without Cabinet authority. The Australian historian Douglas Newton, in The Darkest Days (2014), his hour-by-hour history of the run-up to war, says that “Churchill succumbed to a temptation to frogmarch events.”

Advertisement

Unfair, perhaps, but that was certainly the impression of close colleagues such as Lloyd George, who saw Churchill’s humiliation after the failure of the Dardanelles or Gallipoli Campaign in 1915–1916 as “the Nemesis of the man who has fought for this war for years.” As war loomed, Churchill wrote to his wife, Clementine, with rare self-knowledge, “Everything trends towards catastrophe and collapse. I am interested, geared-up and happy. Is it not horrible to be built like that?” His gaiety did not slacken as the horrors of the trenches began to sink in. He told Margot Asquith in January 1915, “Why, I would not be out of this glorious, delicious war for anything the world could give me… I say, don’t repeat that I said the word ‘delicious’—you know what I mean.”

Anyone who looks, even cursorily, at the first thirty years of Churchill’s life in politics must recognize that his imperviousness to the opinions of others and to facts that didn’t suit him could have the most devastating consequences. Roberts does not shy away from all this, though where he can he palliates Churchill’s ruthlessness, which could be breathtaking. He dismisses, for example, as “completely false” the accusation that, in order to draw the US into World War I, Churchill somehow directed the Lusitania into the path of the U-boats, resulting in the loss of 1,400 lives. But he does not shirk from quoting what he calls Churchill’s “injudicious letter” to Walter Runciman, president of the Board of Trade, urging that “it is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores, in the hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany…. We want the traffic—the more the better; and if some of it gets into trouble, better still.” “Injudicious” seems a rather inadequate adjective.

The trouble was that Churchill’s forcefulness in argument was so often unstoppable. In those grim early months of 1915, he more or less single-handedly persuaded the Cabinet to send the expedition to the Dardanelles as an alternative to “sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders.” Clement Attlee, who fought bravely at Gallipoli, was convinced to his dying day that, if properly led and supported, the operation could have succeeded. Quite a few Churchillians still think the same. But only four years earlier, Churchill himself had said, “It is no longer possible to force the Dardanelles, and nobody should expose a modern fleet to such peril.” The admirals were skeptical too, and Churchill behaved scandalously in pretending that he had their support. At the same time, he was also arguing that “Germany is the foe, and it is bad war to seek cheaper victories and easier antagonists.”

There remain a few supporters also of Churchill’s intervention in 1919 on the side of the White Russians to crush the Bolshevik Revolution. General Denikin was only a few miles from Moscow, it is argued, so surely a bigger push could have sent the bloodthirsty Reds packing and saved Russia and the world from seventy years of misery. But where were the extra troops to come from, and would a war-weary public have agreed to send them? What would the outcome have been—at best an anti-Semitic military dictatorship bent on revenge?

In January 1920 there appeared a cartoon in The Star by the great David Low, entitled “Winston’s bag” and showing Churchill in plus-fours brandishing a shotgun, with five dead cats at his feet labeled “Antwerp Blunder,” “Gallipoli Mistake,” “Russian Bungle,” etc. Thus at the age of forty-five, precisely halfway through his life, Churchill was a byword for rash and costly expeditions. Low could have added a couple more: the decision in 1911 to send troops to quell the miners’ strike at Llanelly and the national railway strike, and his decision in 1920 to send a bunch of roughneck war veterans to reinforce the police and the army against the Irish rebels. The so-called Black and Tans left a trail of murder and mayhem across Ireland, burning small towns and villages and part of the city of Cork. Before the war Churchill had sent eight battleships to smash the Protestant rebellion against Home Rule. He thus has the unique distinction of terrorizing both communities in Ireland at different times.

More momentous was Churchill’s pioneering part in the development of bombing civilians. Fascinated by the technology of war, he was quick to see the potential of the bomber as well as the tank. As early as 1917, he submitted a Cabinet paper advocating the dropping of “not five tons but five hundred tons of bombs each night on the cities and manufacturing establishments” of the enemy, in order to end the war as soon as possible. Hugh Trenchard, the founder of the Royal Air Force, persuaded Churchill that money could be saved if Iraq was “policed from the air,” as Roberts delicately puts it. At the Cairo conference of 1921, egged on by Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence, he sent a force to bomb the villages of Mesopotamia into submission. Afterward Churchill wrote in a memo that if reports of the bombing were to be made public, “it would be regarded as most dishonouring to the air force and prejudicial to our work and use of them. To fire wilfully on women and children is a disgraceful act.” You can almost see the embarrassment steaming off the page. Roberts says nothing of this first bombing of Iraq.

In 1939 both Britain and Germany agreed to FDR’s appeal not to bomb civilian targets outside combat zones. The moment Churchill took over in May 1940, any such inhibitions melted almost overnight, as Richard Overy makes clear in The Bombing War (2013) and Roberts really doesn’t. The new prime minister seemed little bothered by the moral issue. In arguing, vainly, with the Chiefs of Staff to drench the cities of the Ruhr with poison gas, he said that it was just like the bombing of cities, which was viewed as unacceptable in World War I, but “now everybody does it as a matter of course. It is simply a question of fashion changing as she does between long and short skirts for women.” Only when the obliteration of Dresden raised a public outcry did he go through the motions of reconsidering. In an extraordinary aside, Roberts appears to place part of the blame for the huge civilian slaughter at Dresden on an “incompetent local Gauleiter” who “had not provided shelters for more than a small minority of the city’s population.”

It is not as if this aggression softened with old age. In Churchill’s last years as prime minister, he enthusiastically supported the CIA/MI6 coup in Tehran, which overthrew the elected government and paved the way for the return of the shah and, in the longer term, for the Islamic Revolution. He told the CIA operative who organized it, “Young man, if I had been a few years younger, I would have liked nothing better than to have served under your command in this great venture.” When the Suez Crisis loomed, he told then prime minister Anthony Eden to snatch back the canal and turf out Nasser without waiting for any allies, though he later changed his mind, saying, “Never be separated from the Americans.” If Britain is still the Little Satan in large parts of the Middle East and remains a prime target for Islamic and Irish terrorists, there is no single person more responsible than Winston Churchill.

In most of the biographies, all this is not quite ignored, but it is brushed aside or partly excused. The recurring snafus do not fit into the Churchill legend, which has room for only one grand turning point, as the man himself highlighted in the conclusion to The Gathering Storm, from which Roberts draws his subtitle: “I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

Roberts is at his best in recounting these unforgettable scenes and reproducing long passages of those immortal speeches from Churchill’s prime ministership. I must confess that reading the familiar words after a long interval, I often found them painfully moving, their impact all the more irresistible because of their interweaving with my own memories. As a child, for example, I had on my bedroom wall a large colored map of London dating from the late 1940s, called the Bastion of Liberty map. At the top, there was a scroll quoting Churchill’s broadcast of July 14, 1940: “We would rather see London laid in ruins and ashes than that it should be tamely and abjectly enslaved.”

What Roberts brings out so well is the interaction between Churchill and the service chiefs, notably the brilliant, exasperated Field Marshal Alanbrooke, who led them. Due to his axing of elderly and unfit commanders, the prime minister’s military advisers were almost all of the highest caliber. At the age of sixty-five, Churchill finally developed the most un-Churchillian characteristics: a willingness to listen, to be argued out of crazy ideas, and—the most difficult of all for him—to be patient.

This newfound tact, diplomacy, and readiness to give ground are beautifully shown in The Kremlin Letters, an Anglo-Russian collaboration that tells the history of the war through the series of telegrams exchanged among the three Allied leaders, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin. Sometimes stilted or mangled in translation or muddied in the drafting by several hands, these messages nonetheless leave a vivid impression. In passing, Stalin sometimes shows his brutality, blaming the Nazis for the mass murder of Polish officers in Katyn Forest, or saying airily of the kulaks, “they went away.” But most of the time, he is simply a desperate war leader, throwing millions of men into battle while the British can commit only thousands. Churchill never forgets the enormous sacrifices the Russians are making, but at the same time he is never seriously deceived by Stalin’s promises of a free, democratic Poland after the war: “Although I have tried in every way to put myself in sympathy with these Communist leaders, I cannot feel the slightest trust or confidence in them. Force and facts are their only realities.”

Much of the dialogue consists of a prolonged series of demands for a second front from Stalin and a series of excuses from Churchill. Delaying D-Day from the initially hoped-for 1942 into the promised 1943 and the eventual June 1944 was the greatest strategic maneuver of Churchill’s career and the product of a lifetime’s hard-won learning. Here at last his matchless courage and his inextinguishable pugnacity were—the only word is—channeled.

Nobody could deny that this was Churchill’s finest hour. Yet even in the years leading up to that extraordinary moment and more so in the years afterward, a less attractive side to him was revealed. He could not resist harping on the theme that it was not only Britain who stood alone in 1940, but he himself. His lone struggle against the myopic and craven appeasers became an obsession, and almost all his biographers have caught the bug. Roberts is no exception. Again and again, in describing events long after the war, he tags Churchill’s colleagues as Appeasers or Anti-Appeasers, sometimes several times on the same page.

As with the lives of medieval saints, the ups and downs of the early years are described with a relative freedom and candor, but after the wayward youth finds the true faith and performs the deeds that sanctify him, nothing but the most groveling pieties may be rehearsed. Churchill himself laid down the guidelines for his hagiographers. His famous Iron Curtain speech at Fulton, Missouri, on March 5, 1946, not only codified the cold war, it also embedded the appeasement narrative:

Last time I saw it all coming and cried aloud to my own fellow-countrymen and to the world, but no one paid any attention. Up till the year 1933 or even 1935, Germany might have been saved from the awful fate which has overtaken her and we might all have been spared the miseries Hitler let loose upon mankind. There never was a war in all history easier to prevent by timely action than the one which has just desolated such great areas of the globe.

Yet as Robert Rhodes James remarks in Churchill: A Study in Failure, “It is never difficult to speak grandly of a policy of ‘firmness’; it is less easy to spell out where, when and how such a policy could best be applied.” What exactly, for example, should or could Britain have done about Hitler in 1933? As soon as you tiptoe into the argument, you come up against the ambiguities in Churchill’s own position. In August 1919 he supported the introduction of the Ten-Year Rule, which stipulated that Defence Estimates should henceforth be based on the assumption that “the British Empire will not be engaged in any great war during the next ten years and that no Expeditionary Force is required for this purpose.” In 1928, as chancellor of the exchequer (where even he admitted he had been a disaster), he persuaded the Committee of Imperial Defence to make this a rolling rule, rather than one subject to annual review. It was abolished only in March 1932, just before Hitler came to power, but, as Roberts points out, considerably less than ten years before the outbreak of the next world war.

So Churchill had first vigorously opposed any substantial increase in defense spending before both world wars, and had then switched, more or less overnight, with equal vigor to the opposite view. In any case, the early 1930s brought an inconspicuous but steady increase in the British defense budget, as far as the constraints of the straitened economy and war-weary public opinion would allow. The question really comes down to: Was it better to rearm noisily or quietly? Containment, in the shape of dreadnoughts and encircling alliances, hadn’t worked in 1914. How likely was a far more poisonous German militarism to be “disheartened” by more vigorous British preparations for war?

As for the timing, Rhodes James notes what a tame response Churchill offered, as a member of Parliament, to the German occupation of the Rhineland in 1936 (partly because he was then hoping, vainly, to be made defense minister). He had also been willing to contemplate some readjustments to the borders of Czechoslovakia. At Munich, did Chamberlain buy a precious extra year at the expense of national shame, as his few admirers still argue? Or should he have declared war over the Sudetenland rather than over Poland, assuming—a large assumption—that he could have secured the backing of Parliament and the public? The old questions are made no easier to answer by the rancor injected into the debate, not least by Churchill himself.

If you want to see how that rancor continues to poison politics eighty years later, you have only to paddle in the septic waters of the Brexit debate, to which Churchill is by no means irrelevant. Roberts is at pains to point out that though Churchill was wholeheartedly in favor of a European Union after the war, he did not want Britain to be “an ordinary member” of it. “We are with them, but not of them,” he said in the House of Commons in 1953. On this point, Boris Johnson, the leading figure in the Leave campaign, and Roberts are quite correct. Churchill consistently believed that Britain must be friends and sponsors of any such union, but that its destiny lay elsewhere: “We cannot subordinate ourselves or the control of British policy to federal authorities.” When General Montgomery visited Churchill in the hospital in the summer of 1962, he found the great man in bed smoking a cigar and fulminating against Britain’s proposed entry into the Common Market.

His mother’s American blood never ceased to throb in his veins. The crux of the Fulton speech, Churchill said, was “the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples. This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States.” This vision, or illusion, continues to captivate Brexiteers today. The conservative member of Parliament Jacob Rees-Mogg has spoken longingly of closer ties with Donald Trump. Roberts himself is a devotee of what he calls “the Anglosphere”—a major theme in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900 (2006). After what he called “the British people’s heroic Brexit vote,” he wrote that he hoped to resurrect “Winston Churchill’s great dream” of a federation between the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Today, Brexiteers are increasingly eager to make a clean break with the EU and come out with no deal, for as Simon Nixon wrote in the Times, “The real problem is that Brexiteers know that a deep free-trade deal with the EU would preclude their real prize: a deep free-trade deal with the US.” They don’t mind being “vassals,” to use their Churchillian term of abuse, so long as they are American vassals. Underlying all this is an incurable English exceptionalism, which can be traced back to 1940. That brief imperishable moment in our island story—how easily one slips into the lingo—is still the defining moment. Standing alone is the essence of our nationhood. As a vision, it retains the true Churchillian imprint. As a reality, the Brexiteers may yet have to learn the knack of walking away from disaster as if it had nothing to do with them. That knack too was part of Churchill’s secret.