In 1854 Gustave Courbet sent his patron and friend the rich philanthropist Alfred Bruyas a self-portrait, accompanying it with a letter:

It is the portrait of a fanatic, an ascetic. It is the portrait of a man who, disillusioned by the nonsense that made up his education, seeks to live by his own principles. I have done a good many self-portraits in my life, as my attitude gradually changed. One could say that I have written my autobiography.

This statement was somewhat premature (he was only forty-five at the time), but it is true that he was fascinated by his own appearance and some twenty self-portraits are extant. In the 1860s, when Emile Zola was trying to sum up Courbet’s achievement, he wrote that he saw him as “simply a personality.” Certainly Courbet made much of his own personality, and the revolution that he effected owed more than a little to the vividness of his presence and to the myth that he very soon succeeded in building up around himself.

In fact, at the time Courbet was sure of his principles and of the way he felt he must manipulate his career. In the restless political climate of the decades following the Revolution and right through until the 1870s, Courbet’s views were consistently as far to the left as it was possible to be. In a letter to the writer Francis Wey and his wife in 1850 he declared himself thus:

I must lead the life of a savage…. The people have my sympathy. I must turn to them directly,…and they must provide me with a living …so that their judgement won’t be influenced by gratitude. They are right. I am eager to learn and to that end I will be so outrageous that I’ll give everyone the power to tell me the cruelest truths.

The publication of Courbet’s collected letters in 1992, edited and translated by Petra ten-Doesschate Chu,1 put an end to the popularly held view of Courbet as a somewhat boorish provincial who had taken Paris by storm with his pictorial genius. Now Chu has published an interpretative study of his art, The Most Arrogant Man in France (the title is from a quote by Courbet himself), with the subtitle “Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture.” The letters and the book, taken together, make a splendid diptych and, along with T.J. Clark’s pioneering Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the Second French Republic of 1973, will surely become essential for all future Courbet studies.

The title of Chu’s book is self-explanatory, but in the exploration of her theme, she inevitably casts light on the artist’s character. Courbet was certainly arrogant to the highest degree. But he was intelligent and literate, albeit in a slightly quirky way. He had a sound if somewhat selective education in his native Franche-Comté; his letters from boarding school in Besançon to his parents back in Ornans criticize gaps in the curriculum and the shortcomings of some of his teachers. He was a born rebel and remained one until his death in exile. He was totally self-centered yet capable of warmth and affection toward his family.2

As his career progressed he indulged in much litigation. He could be duplicitous but could also show loyalty to friends and generosity to younger artists; he lent money to Monet. Yet the contradictions in his behavior and personality do not indicate a complex character but rather simply reveal a monumental self-absorption. His vainglory was so open as to be candid. He could be a liar on such a scale as to be quite engaging. Discussing the itinerant Irishwoman suckling a baby who appears in his great Atelier of 1855 he claimed to have seen her on the streets of London. Apart from the fact that there is no documentary evidence to support a London visit, he also claimed to have had an interesting conversation there with Hogarth, who had, of course, been dead for over forty years.

Courbet reached Paris in 1839. Nine years later he moved into a studio in the rue Hautefeuille, a few paces away from the Brasserie Andler in the Latin Quarter, which became almost a second home to him. The Andler was perhaps the most famous meeting place of the day for writers of all sorts in the city. By far the most distinguished of the habitués was Baudelaire, who was to be important for Courbet in the 1840s despite the incompatability of their characters. At the Andler Courbet also encountered, among a host of others, Théophile Gautier, Champfleury (a pseudonym),3 Jules Castagnary, and Alfred Murger, who are relevant to the painter in different ways.

Gautier, a confirmed Romantic, was perhaps the most celebrated art critic of his time. Courbet flirted with him by post, perhaps hoping to be mentioned in a review; there was no response. Gautier subsequently wrote unfavorably about Courbet’s art. Courbet, however, had long since realized that unfavorable reviews could be just as helpful in attracting public attention as those that flattered. Champfleury, a realist novelist and art critic, was initially the most enthusiastic champion of Courbet’s art, until they quarreled. Castagnary stepped into his shoes and remained staunch to the very end. Murger’s somewhat vapid Scénes de la vie de Bohème (1852) gives us an insight into the sort of life Courbet and his friends were leading; it was a roman à clef and Courbet knew personally the prototypes for its principal characters.

Advertisement

But the two most important influences on Courbet’s thought were surely Max Buchon (a friend since school days), an author of rural novels and a confirmed, even fanatical, republican (a position that forced him into exile in Belgium for a considerable period), and above all Pierre Joseph Proudhon, the philosopher and revolutionary thinker, most famous perhaps for his statement of 1840, “Qu’est-ce que propriété?” (“What is property? Property is theft”), which shot him to notoriety and made a strong impression on Courbet. Together they planned a book on the visual arts.

Throughout his life Courbet seems to have preferred the company of writers to that of other painters. One of the few disappointments of the Letters is that he almost never discusses any art other than his own, which he deals with almost entirely in financial terms; money is one of the leitmotifs of his correspondence. He recognized the achievements of Delacroix, whom he viewed with a certain grudging admiration, touched by envy. He knew Corot and was aware of the landscapes of the Barbizon School—he sometimes set up an easel there himself. He acknowledged Millet by lifting a pose from him. In 1856 he worked next to Whistler in Trouville, at the time a newly fashionable resort on the Normandy coast.

But basically he felt more at home with lesser artists who presented him with no challenge. He didn’t read all that much but was aware of what was going on around him in the world of letters. In an early stage of his career he had produced some pictures based on famous books, probably hoping the subject matter would impress the jury of the Salon. However, as Chu demonstrates time and again, it was the popular press that he studied most devoutly; after his death in Switzerland in 1877 a large cupboard in his rooms was found stuffed with newspapers.

The Courbet exhibition on view at the Grand Palais in Paris came as close to being definitive as seems possible. (Most but not all of the pictures will be on show beginning this month at the Metropolitan Museum, which also displays several paintings not in the Paris exhibition.) Of all French nineteenth-century artists Courbet was the most physical in his handling of paint, and his distinctive artistic presence filled the galleries in an almost palpable fashion. Wandering through them one was struck by the variety of ways he uses paint, stroking it, smudging it with rags, occasionally even using his bare hands to manipulate it. It seems that he treated paint as if he were touching human flesh, caressing it, kneading it, at times even assaulting it; and this is true not only of the nudes and figure pieces but even of many of the still lifes, the flower pieces, and the more verdant landscapes.

Courbet was a productive artist and the exhibition is very large. Despite the consistency of his political views and his adherence to Realism, his iconography expanded as did his treatment of it, so that his aesthetics shifted somewhat, too. The exhibition’s organizers, while they adhere roughly to chronology, have broken the display down into successive sections dealing with separate themes—“From Intimacy to History” or “The Manifestos”—like chapters in a book, and a similar sequence is to be followed in New York.

The first section deals predictably and rightly with Courbet’s early self-portraits. Before he visited Amsterdam in 1844 Courbet had already fallen under the spell of Rembrandt’s self-portraits and the visit confirmed him in his devotion to the Dutchman, who was perhaps his closest visual attachment in the early years of his career. Certainly the example of Rembrandt is overt in several of the first self-portraits, and his ghost hovers over the series as a whole. A comparison is revealing. Although Rembrandt often showed himself in different forms of costume, sometimes exotic, his eyes always hold the viewer’s own: as he looks into a mirror he also looks at us, and we sense him looking down into his own psyche, searching for ways to further penetrate his identity in order to seek new aspects of his character and hence expand his art.

Advertisement

Courbet’s self-portraits, on the other hand, are pure theater. His eyes seldom lock with ours; rather he enacts for us a series of impersonations. The two portraits of himself with his black cocker spaniel, both of 1842, are still overtly Rembrandtesque: in the first he presents himself as cultivated and slightly aloof; in the second, he looks positively princely, and so in a sense he was. Social distinctions in the provinces were every bit as complex as those in big cities. The Courbets were the first family of Ornans and very much aware of that fact.

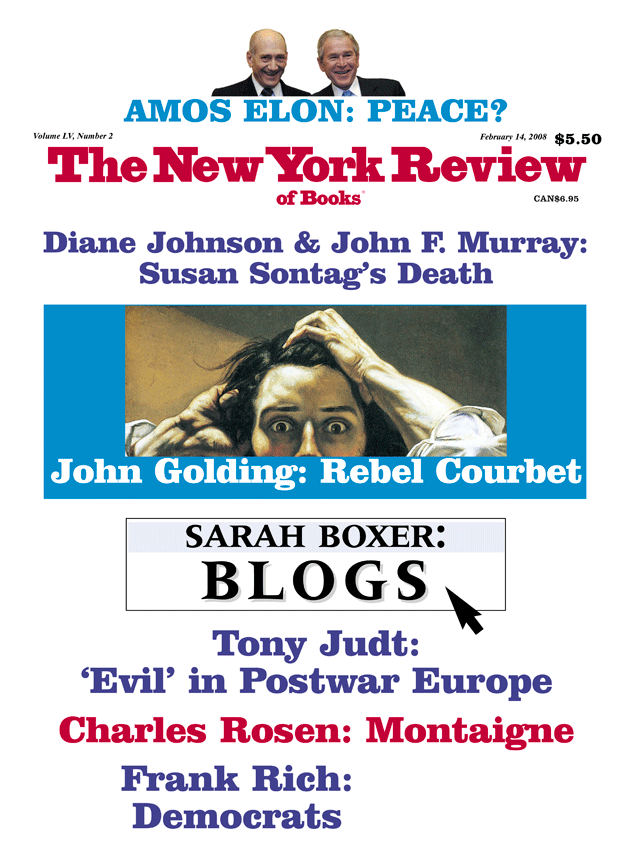

Other, slightly later self-portraits show Courbet as disheveled and dreaming, one even as wounded; these suggest Romantic conceptions of the misunderstood artist, neglected and abused. In by far the most dramatic depiction of himself, known as Despair (1844–1845), he stares past us wild-eyed and distraught, tearing at his hair.4 The portrait that closes this sequence is the most straightforward and one of the least known. It was painted in 1852, a year after the sensation caused by the Burial at Ornans at the Salon of 1851. This time Courbet strikes us as slightly defiant, proud of his new notoriety and of his physical beauty. Taken together these portraits tell the story of one of the world’s great love affairs, that of Courbet with himself.

Courbet gained fame with a series of large “manifesto” paintings. An After-Dinner at Ornans shows his father and three family friends in the kitchen of one of them, Urbain Cuenot; another friend, Alphonse Promayet, entertains the small group on his fiddle. The picture is large (77 x 101 inches) and was attacked as a blown-up genre painting, which is exactly what it is; but it is genre made monumental (the only truly valid parallel is with the monolithic seventeenth-century peasant pictures of the Le Nain family). The figures, boldly rendered in heavy chiaroscuro, have an extraordinary gravitas, and surely owe a lot to Spanish seventeenth-century painting; in Paris at this time there was great enthusiasm for Spanish culture. The depiction of the third friend, Marlet, seen from the back and slightly angled into shallow depth, is counteracted by the position of the hunting dog asleep under his chair. This figure looks straight ahead to Cézanne’s late card players of the 1890s.

The Burial at Ornans is an even larger painting, strongly horizontal. Because of the subject it is ceremonial in feeling, and it reveals a totally new aspect of history painting. Its ambitions match its scale. The Parisian public were baffled by it because they thought it difficult to situate socially and hence possibly subversive.5 The citizens of Ornans, who originally were anxious to volunteer as models, became unhappy after they heard the reactions in the capital. The picture is factually descriptive. The pallbearers advance from the left but are visually pressed forward by the rocky outcrops of the terrain above them, so that the composition is very flat and frieze-like.6 It is saved from any form of emotionalism by the fact that we see only a corner of the empty grave in the center of the picture. To the right are the mourners. They are not peasants but rather rentiers or landowners. Some of them may wear peasant smocks by day, but here they appear in their Sunday best.

If the figures of the After-Dinner emerge out of the shadows, the faces of the personalities here emerge from above the black of their garments. The scrubbiness of the paint may reflect the fact that while the largest wall of Courbet’s studio in Ornans was wide enough to contain the picture, the room had little depth and he would have been unable to study it from a distance. Despite the fact that Courbet would have placed the picture in his own category of “ironic” works, there is little overt social comment except in the portrayal of the clergy, who come out of it predictably badly, their faces red and bloated from self-indulgence.

In a third painting of 1850, The Stone Breakers (now lost),7 Courbet lightened his tonalities, almost to blondness, in order to paint in greater detail; the effect borders on the photographic. Proudhon was to classify this work as the first socialist painting and as “a satire on our industrial civilization…which yet is unable to to liberate man from the most backbreaking toil.” Courbet was later somewhat evasive and claimed he had simply recorded something he had seen but added proudly that he had stirred up “the social question.” A fourth painting, The Bathers of 1854, caused a scandal of a different kind; viewers at the Salon were shocked by the ample proportions of the model seen from the back. The Empress Eugénie compared her to one of Rosa Bonheur’s workhorses and the emperor actually struck the painting with his riding crop.

Courbet’s Atelier, or, to give it its full title, The Painter’s Studio: Real Allegory Summing up a Seven-Year Phase of My Artistic Life of 1855, is one of the greatest masterpieces of the nineteenth century. It is vast (142 x 236 inches) and it dominated the extensive one-man exhibition he mounted in a large pavilion built at his own expense on the avenue Montaigne; it ran for six months and attracted hordes of visitors. (The picture is too large and fragile to come to New York.) Other artists had staged solo exhibitions, but never on this scale. Space had always been Courbet’s weak point; the middle grounds of his pictures are often unconvincing and can give the eye a hard time. But in the Atelier the space is dreamlike, so vast and amorphous that it cannot be taken in all at once. To the right of the painting stand important figures from his life: Champfleury (representing prose), Max Buchon (Realist poetry), Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (socialism), Alphonse Promayet (music), Alfred Bruyas (patronage), Charles Baudelaire (fame?), two lovers (free love), and a bourgeois couple (his audience).

On the left-hand side are allegorical figures representing various strata of society: the Irishwoman (poverty), a traveling salesman of used clothes (exploitation of the gullible poor), a huntsman (healthy rural life) and so on; at their feet lies a dagger, a troubadour hat, and a guitar, presumably standing for the discarded trappings of Romanticism; behind them is a painting of an écorché, a flayed body, and below it a skull, signaling the demise of academic methods. Both flanks of the painting lead the eye toward its center; the right-hand side is in strong recessive perspective, while the left curves inward more gently. And there, of course, is Courbet, still very handsome, at his easel. Behind him is his muse, one of the most beautiful of all his nudes. In front of him, with his back toward us, is a small boy with his cat, representing, presumably, the homage of future generations and Courbet’s love of domestic animals. Courbet himself admitted that he was out to mystify, and added that every viewer was free to bring his own interpretation to what he was looking at. Yet this is the last great painting of the century that can be read by using the kind of references that would hitherto have been reserved to elucidate the content of large-scale historical scenes.

The section of the exhibition following the Atelier is dedicated to “Landscapes.” The earliest of these, depicting the country outside Ornans, are painted with love and belong to a tradition of French landscape painting ranging from Claude through to the early Corot. One of the most famous of the landscapes, The Oak of Flagey (1864), is in fact a mighty portrait of a famous landmark and is awe-inspiring. Other landscapes would look at home in a display of the Barbizon School. Most immediately striking are the “source” paintings depicting the sources of the Loue River. Here Courbet’s palette-knife technique comes into full play; the rocky surfaces are pressed forward and our eyes seem to actually touch them.

Period photographs are liberally scattered throughout the exhibition. Many of them are simply documentary; others are beautiful, although I doubt whether they would have been classified as works of art at the time. The photographs, like the individual paintings, are given short essays on their own; they seem very relevant here, as do the the ones of nude models in subsequent sections. It has long been known that Courbet sometimes worked from photographs but clearly he relied on them more frequently than has hitherto been recognized.

Used in the seascapes, the palette-knife passages are often less successful—the spume or spray sometimes looks slightly too solid. The seascapes tend to divide opinion, and many of them were produced to sell easily, but at their best they are magnificent; whatever the motives for producing them, when in front of the easel Courbet was entirely his own man. He was a natural painter, and he was in love with paint and the endless possibilities of its effects. He spoke of being overawed by the vastness of the ocean; and here there was no middle ground to cope with as the seas recede into infinity. Courbet was a big man in every sense of the word and in visual matters he thought big, too. And he worked unafraid.

The next section was somewhat bafflingly entitled “La Tentation Moderne.” (In New York it will be called “The Painter of Modern Life.”) After all, by the late 1850s Courbet had established himself as the most controversial, important, and radical painter in France, possibly in Europe. The section is introduced by a short quote from Champfleury: “Our Friend has lost his way. He has tried too hard to feel the pulse of the public, He is trying to please it.” (Hence the breakup of a close friendship.) There is more than an element of truth in this. And despite the wonders still to come, the truly gripping revolutionary years were over. The portraits shown here are duller than the ones that precede them. The men are clearly important or affluent, although the large posthumous depiction of Proudhon (1865–1867), who was out to destroy social distinctions, strikes a very different note.

The portraits of women are almost invariably finer than those of the men; apart from other, obvious reasons, Courbet was seriously interested in dress and fashion. One of the most beautiful of all is Jo, la belle Irlandaise, a particular favorite of Courbet’s. It depicts Joanna Hifferman, a mistress of Whistler’s, who after she broke with the brilliant but tiresome American returned to France and, one assumes, to Courbet.

A large, truly subversive picture, Les Demoiselles des bords de la Seine (été) (1856–1857), demonstrates that Courbet could still upset the Salon applecart when he chose to do so. It depicts two somewhat gross young women, presumably of easy virtue, enjoying an afternoon off on the riverbank; one of them has removed some of her clothes. Chu’s analysis of the ambiguities of this picture is particularly brilliant: she notes, for example, that even though the depiction of a woman in her underwear was unusual “before and even after Courbet,” no contemporary reviewer mentioned it, perhaps because “male critics were so little attuned to the details of fashion that they confused underwear with the newly fashionable white dress of the mid-1850s.”

The nudes of the 1860s are among the grandest ever painted. In 1866 Zola was to extol Courbet as a painter of flesh who could claim kinship with Veronese, Rembrandt, and Titian, and again Zola was right. Two of the finest life-size nudes are in the exhibition, both of 1866: Le Sommeil and La Femme au perroquet. Yet inevitably, attention is drawn to a smaller picture, L’Origine du monde (also 1866), which has become perhaps the most notorious painting of the nineteenth century. It is in effect a portrait of a woman’s exposed genitalia seen from slightly below and almost certainly taken from a photograph (there were lots of them around at the time to choose from). It is the subject of a book-length biography all its own, by Thierry Savatier, a writer specializing in nineteenth-century French literature and its erotica. In its third edition, it reads like a high-grade detective novel.

Appropriately enough, the picture had an active, if secret, life. It was originally painted for Kalil-Bey, Ottoman ambassador to Paris in the 1860s. The ambassador had tried to buy Courbet’s Venus and Psyche of 1863, yet another controversial piece because of its lesbian undertones. This had already been sold (and has subsequently disappeared from view). Courbet offered to paint a sequel to it, Le Sommeil (before and after the love act), and then threw in the Origine as an extra. It adorned the ambassador’s palatial bathroom, hidden behind a green baize curtain. Kalil-Bey was eventually forced to sell his substantial collection to meet his more than substantial debts.

In the following decades the painting was presumably viewed furtively; then in 1913 it traveled to Budapest, to be housed once more in an opulent bathroom, that of Baron Ferenc Hatvany. It was now in a specially designed frame, which meant that when not being enjoyed the Origine could be shielded under a harmless Courbet winter landscape. At the time of World War II, when the city was threatened by advancing Russian forces, the picture was placed in a bank vault, only to be looted by the invaders. It was subsequently restored to its owner and eventually passed into the hands of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who kept it in his study masked by a quasi-abstract painting by his friend André Masson of the same subject, but veiled and opaque.

Courbet himself had been characteristically modest about his achievement:

You think this beautiful…and you are right…. Yes, it is very beautiful, and listen, Titian. Veronese, THEIR RAPHAEL, I MYSELF, none of us have ever done anything more beautiful….

The picture is certainly unforgettable, and has invoked comparisons with Courbet’s “source” pictures—moist, mossy surfaces protecting yet also revealing secret orifices which invite exploration.8

Courbet had always been interested in politics. But it was only during the Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of the Commune in March 1871 that he became actively involved in them. For a while he was in his element. In April 1871 he writes to his family:

Here I am, thanks to the people of Paris, up to my neck in politics: president of the Federation of Artists, member of the Commune, delegate to the office of the Mayor, delegate to [the Ministry] of Public Education, four of the most important offices in Paris. I get up, I eat breakfast, and I sit and I preside twelve hours a day. My head is beginning to feel like a baked apple.

He now saw himself as, in a way, ruling the art scene of Paris. But it was to prove his undoing. Much has been written about his 1870 proposal to the pre-Commune government to dismantle the column in the Place Vendôme—seen by many as a symbol of Napoleonic imperialism—and reinstall it at the Invalides. In fact, it was toppled by the decision of the Commune, with Courbet present. He had advocated retaining the bronze reliefs that adorned it, and they were preserved. The Commune was suppressed on May 28, 1871, and on June 13 Courbet was arrested.

He was by now being pilloried in the press and his supporters were falling off fast; even the hitherto loyal Bruyas was distancing himself. Courbet was manacled and led through the streets, and there is surely something genuinely tragic in the spectacle of the great, bearlike figure being brought to bay by the forces of reaction. He was thrown into a series of prisons, most notably the notorious Saint Pélagie, where he found some solace in painting still lifes of the fruit brought to him by visitors. He was released in early 1872, but further prosecutions followed and he was charged with the expenses of reinstalling the column. In July 1873 he went into self-imposed exile in Switzerland. He took with him a team of four assistants, all of them indifferent artists. Many of the Swiss landscapes that poured out from his studio never felt the touch of his hand except for the signatures they bear.

The penultimate section of the exhibition contains a galaxy of large pictures of hunting. It was a sport in which Courbet had always reveled. At their best, as for example in the gigantic Spring Rut, Battle of Stags (1861), these pictures show extraordinary technical virtuosity, and pulse with a physicality that can at times be almost disturbing. Some, on the other hand, have a stitched-up quality; borrowings from other artists, especially Frans Snyders, and, closer to him in time, Edwin Landseer, can be a little obvious and artificial. The final section has about it a muted, valedictory air. It includes some truly lovely small still lifes, of 1871–1872, which convey a sense of wistfulness, almost of humility, and a couple of Swiss landscapes that are almost certainly Courbet’s own and radiate a sense of loneliness in their somewhat glacial atmosphere. There are three beautifully painted pictures of dead trout, their mouths open as if still gasping for air.

In his Swiss exile, well-wishing friends unwisely supplied Courbet with barrels of brandy, which seem to have gone down at an alarming rate; he was also now onto absinthe. Toward the very end his once-fine body had become grotesquely inflated, and he cherished the fantasy that if only he could be lowered into the cold waters of the lake that lay below him, things might still come right for him. He died on December 31, 1877, of dropsy, induced by drink.

The catalog is the work of a team from the Musée d’Orsay and, although somewhat unwieldy, it makes an invaluable addition to Courbet scholarship. It is also good to have the collected writings on Courbet by Linda Nochlin, long a pioneer in this field, collected into a single volume.

This Issue

February 14, 2008

-

1

University of Chicago Press; see Julian Barnes’s fine review in these pages, “↩

-

2

In the last stages of his life, he did however develop a black hatred toward his eldest sister Zoë. ↩

-

3

His real name was Jules-François-Félix Fleury-Husson. ↩

-

4

This is the image that was chosen for the traditional banners that Paris sports to advertise major exhibitions. It would have pleased Courbet to be presiding over hundreds of thousands Parisians as they roamed through the streets of the capital. And the fact that this relatively small picture survives magnificently the test of being blown up to twenty or thirty times the size of the original testifies to its power and the beauty of its paint effects. It will be seen in the exhibition and on posters in New York. ↩

-

5

The After-Dinner had won a gold medal at the previous Salon. This meant that Courbet no longer had to submit future entries to the jury; if it were not for this the Burial would probably have been rejected. ↩

-

6

Champfleury was already writing about the importance to Courbet of the “flat” images d’Épinal—prints of popular subjects named after a nineteenth-century printing house that made them—and other popular images reproduced mostly from woodcuts. ↩

-

7

The picture when last seen was housed in the Dresden Kunsthaus and was presumably destroyed in the wholesale bombings of the city by the British during World War II. ↩

-

8

After Lacan’s death his widow Sylvia (she had been previously married to Georges Bataille, famous for his own erotic writings) lent it to a few exhibitions, none of them in Paris. In 1995, after Sylvia’s death, it was accepted by the state in lieu of estate taxes and was put on show at the Musée d’Orsay the following year, accompanied by much publicity. In the Grand Palais the picture, together with relevant additional matter, was housed in a pavilion in the center of the room dedicated to nudes, presumably to allow the guards to deny access to parties of schoolchildren. This had the unfortunate effect of not allowing one to stand far enough back to fully appreciate the splendors of the two great paintings, the nudes of 1866, mentioned above. It is to be hoped that when the exhibition reaches New York the Metropolitan Museum will find a more satisfactory solution to this problem. ↩