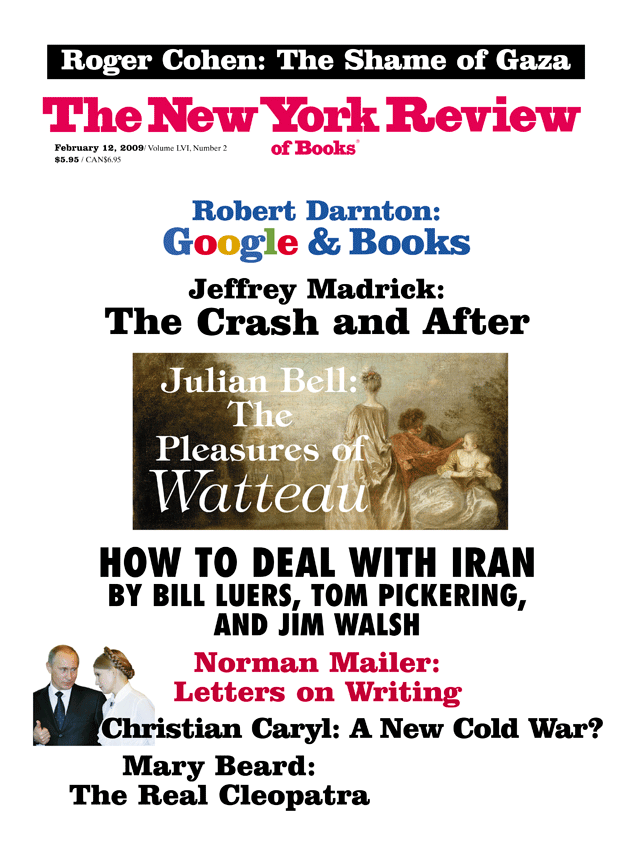

Antoine’s Alphabet, the new book by the New York art critic Jed Perl, is a set of reflections centered on the painter Antoine Watteau. Some sixty short texts are laid out according to the alphabetical order of their headings. These spell out some themes that anyone familiar with the painter might expect—“Actors,” “Commedia dell’arte,” “Rococo”—and some others they might not—“Beardsley,” “Flaubert,” “Kleist,” “New York City.” The alphabet, in fact, turns out to be a minimum handhold on a bus ride that lurches and deviates, rattling along on sheer intuition.

In a prologue Perl tells us he is going to write about his “favorite painter.” Decades passed in Watteau’s sustaining imaginative company have given him an expanded sense of what might be “Watteauesque”: he is happy to proclaim affinities, strike up correspondences, and explore parallels in whatsoever direction he fancies. Watteau, in his eyes, seems to add new insights into the personas of Diaghilev and Katharine Hepburn. His assured sense of that master’s oeuvre encourages Perl to sketch out little fictions about other painters—giving voice, for instance, to Cézanne’s feelings as he travails over his Pierrot and Harlequin.

Describing his passion for the artist also involves Perl in telling us about his friends and a little about his childhood. One entry becomes a short prose poem on the flavor of New York evenings; another concerns a nineteenth-century chocolate advertisement that reproduces a Watteau painting; and then there are sundry freestanding aphorisms on art and culture. However one approaches it, the little volume in which all these impulses are collected stands sui generis —a personal testament, a labor of love. What it will not really stand up as is a viewer’s guide. While underpinned by study of the best relevant scholarship, it only obliquely yields up the facts about the actual historical Watteau.

In 1709, just as his foot was planted on the art-world ladder, Watteau briefly went back home to Valenciennes. He soon thought better of it, but not before he had sketched material for his most laconic group of pictures, scenes of soldiers camped in makeshift countryside bivouacs. The troops he drew were probably returning from the Battle of Malplaquet, one of the series of French defeats that darkened the national mood during the last years of the long reign of Louis XIV.

The pictorial veins that Watteau went on to work catered to a craving for imaginative escape that surged among Parisians, who had long been leery of Louis’s domineering and bellicose statism. City dwellers, whether aristocratic or bourgeois, found their common language for in-jokes and badinage in the theater. Fashionable taste around 1710 favored shows by the unlicensed players’ companies: these featured harlequins and pierrots, in the face of an official ban on Italian commedia dell’arte and of a royal monopoly granted the Comédie-Française. The pursuit of pleasure sent the same crowds out of town on suburban excursions, taking for instance the boat ride down the Seine to Saint-Cloud with its château, its park, and its bowers.

One aspect of the scene complemented the other for, in the argot of theater scripts, that downriver rendezvous for picnics and tumbles in the bushes turned into “Cythera,” the legendary homeland of the goddess Venus. And this fancy of a charmed, erotically charged elsewhere was acompanied by a fashion in behavior—“galanterie,” a floating notion of the light, the easy, and the flirtatious in which both nobles and commoners, equally averse to Louis’s stern militarism, could participate.

Tokens and encapsulations of that fleeting grace became Watteau’s stock-in-trade. With a winning facility at rendering satins, with a constant supply of figure studies fostered by his zeal for sketching, he could conjure up variation after variation out of the stock units of amorously inclined man, amorously susceptible woman, and bosky parkland—often swelling the numbers into a party ( une fête ), commonly introducing one or more stage personas and very likely a guitar. These novel compositions disarmed the board of the Académie Royale, which admitted him as a member in 1712, and through this elevation Watteau might have moved over to work on the exalted, properly noble scale—executing the seven-foot classical tragic narratives that had been the Académie’s mainstay since its founding in 1648—had he so wished. But he let the delectable little fêtes galantes preoccupy him through the five following years, ignoring the Académie’s repeated reminders to deliver the big reception piece that was its due.

Advertisement

Finally, a grandiose transmogrification of the trip to Saint-Cloud was submitted, to fix Watteau’s art for once and for always in people’s minds. Since 1717 The Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera, with its curling ribbon of fine-dressed lovers and its gilded barque at the woodland waterside, has had an almost permanent place in the Louvre (which in those days supplied the Académie with its exhibition space).2 This ambitious piece was probably followed by Watteau’s other great work in the communal memory— Gilles, the full-length portrait of a pierrot in white satins, brimming with a strange passivity (see illustration on page 14).

Did these canvases show an artist at last trying, as he neared his mid-thirties, to make a serious impression in Paris? If there was such a strategy, it had to be discontinued: in 1719 Watteau departed the city, to spend a year in London seeking the services of a famous English medic. Tuberculosis had set in. The services proved ineffectual. When he returned, he begged his picture-dealer friend Gersaint to let him paint the shop sign for his premises on the Pont Nôtre-Dame. Gersaint’s Shopsign, this wry capsize of categories—academician turns artisan? artists’ oils on the streetfront? (passersby loved it, but Gersaint had to take it down after two weeks)—proved not only his largest painting, a ten-foot pan of the picture-shop interior and its clients, but his next-to-last. A crucifixion, now lost, was painted for the friend in orders who administered the last rites a few weeks later in July 1721.

Artists came to see that his canvases were joyful in their very absence of academic method—in the way that Watteau freely slung together sketches from his stash that happened to fit in order to get a composition going. A wider audience came to see that they were joyful in their avoidance also of academic subject matter. Rather than some solemn Wrath of Achilles, say (a theme deemed proper around the same time by Antoine Coypel, the director of the Académie), Watteau was painting guitars and masks and taffeta, fans and bouquets, comical lechers, pretty girls galore—above all, love.

In fact here was, as it turned out, the pictorial apostle of the great rush to hedonism that French society permitted itself after Louis XIV finally expired in 1715—the period known as the Regency (since the new king was in his minority), marked by its reckless free-spending, constant partying, and satire, with the banned commedia dell’arte returning to town. All of which Watteau himself half-acknowledged in his final bow to that society, Gersaint’s Shopsign —in which we see a shophand unceremoniously packing away a portrait of the gloomy old grand monarque, disdained by a clientele far more interested in exquisite consumer desirables.

As the art of Watteau itself became a consumer desirable, it had an effect on French painting at large throughout the mid-eighteenth century—not just because the imitators Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater helped disseminate its look, but because the enormously productive king’s painter François Boucher was responsive to its new ways of sketching and composing. Thus, retrospectively, Watteau became “rococo”—the label coined for Boucher and his associates at the century’s end, when their irregular and “frivolous” aesthetic had fallen right out of critical and political favor. It was at this point that some student radical, one of the Académie’s “Primitives,” got “carried away by his antipathy” for The Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera and “raised himself upon his bench and vigorously punched the painting to destroy it” (according to a contemporary’s memoirs).3 Very likely its pictured galants — so fancy, so feminized—seemed an affront to his revolutionary virility. The canvas was withdrawn to the Louvre’s attics.

Thus the Goncourts set up a line of interpretation that has been orthodoxy ever since. Watteau became the visual poet of yearnings that might never be consummated, of youth that is foolish and brief, of fine charades that tremble with anxiety, of trysts that may end in tristesse. Somehow, the neuroses of the man himself, of which his friends could see no trace in his art, were belatedly discovered to lurk there after all, just beneath the bright colorful surface. No doubt a factor in this turnaround is sheer temporal distance—the sense that the ancien régime as epitomized in Watteau’s work is the great “before,” on the other side of the Revolution and industrialization and the Romanticism that spawned the very nostalgia we bring to our viewing, imbuing his images with a pathos beyond their maker’s conception. But is that tinting by hindsight to be argued away? In a monograph published in 1984, the art historian Donald Posner tried to counter the transformation of Watteau into a poet of fragility and angst and restore the canvases to what he believed was their original, shadow-free coloration.

Advertisement

“Robust and virile,” Posner termed the art—but those labels won’t stick. Watteau’s new advocate is anything but a historical purist. Jed Perl wants to steep the paintings in the world he currently inhabits, and vice versa; in the process, Watteau’s own moment of novelty gets overlaid with the many versions of the modern that ensued. The portrait of the pierrot Gilles may record a certain stage act of the 1710s, but equally it taps us into the revival of mime theater in 1830s Paris and the resuscitation of that revival in Marcel Carné’s great film of 1945, Les Enfants du Paradis —not to mention Cézanne’s pictorial dalliances with pierrots in the 1880s, and Picasso’s after the Great War. And these give us a larger sense of what Watteau was up to, for when Perl bounces back at length to consider the original figure, he can argue that in the great blank of his suit of white satin and the small blank of his radically irresolute face, Gilles suggests a characteristically modernist anxiety:

White equals possibility—the white paper to write on or draw on or compose on, the white canvas to paint on, but also the white of the empty gallery and the empty stage. For artists, this is the deep, primitive fascination of the white clown…. Gilles is raising a question about the possibilities of creation. How can I move from the nothingness of a beginning to the completeness of a work of art?… The quizzical, uneasy look on the clown’s face is the look of the work of art that is not yet created, that is still wondering what it will be.

That interpretation stirs, whether or not it wholly satisfies. At the least, it seems to rise to address the enigmas posed by Watteau’s extraordinary image in a way that no purely historical examination of the primary evidence could. Surely we walk galleries such as the Louvre in the hope that they will pounce on us surprises that override time, pasts that assail our present. But we may need some preparatory softening up of our defenses. It’s a task at which Perl excels.

It almost goes without saying that arguing for Watteau involves recruiting him as an embodiment of “modernity,” the omnipresent word that conveniently resists definition. That is how nearly all art writers instinctually proceed. Gersaint’s Shopsign with its “poetics of shopping” becomes “the greatest painting of modern life ever done.” Inevitably also, Watteau is co-opted as a spokesman for the cause of emotional complexity:

Our feelings about things, our perceptions of things are always multiplying, or at least they are always slipping into other feelings, other perceptions—this is what Watteau wants to tell us.

Equally,

Watteau is fascinated, above all else, by the impossibility of ever being sure of who you are, at least for more than a very brief time. He is a master of in-between situations….

Those speech-bubbles in the mouth of a painter whose thoughts lie almost wholly unrecorded are fairly cheeky—still more, the supposed letter to a friend that Perl invents in his name.

Yet the history of French painting will broadly bear them out: Watteau introduced just such a change of accent. His improvisations bade farewell to the objectives of completeness and coherence spelled out by Poussin in the previous century. Hints and indeterminacies dangled in their stead. A wonderful tiny canvas in the Louvre known as The Two Cousins features a park lake at evening (see illustration on page 12). One couple is flirting by its bank, another lingers between distant statues reflected in its waters; but all turns on the back of a lone blonde in a shimmering yellow gown, standing at an anomalous angle to those others and presenting a vacant yet potent vehicle for our empathy. She is another blank, comparable to that offered by Gilles. At such moments, writes Perl, “what we are witnessing is something like the death of storytelling.”

Extolling Watteau as the kind of modernist who subscribes to “the questioning of meaning as a new form of meaning,” Perl finds an ally in Samuel Beckett, who, he claims, sensed in the painter’s images “a tragic sense of the mismatch between the figure and the environment.” Do the lake waters and shadowy trees harmonize (as they might in a Poussin) with the characters’ emotions, or isn’t it rather a case of a mute indifference confronting a stalled hesitancy? That “unalterable alienness of the 2 phenomena,” as Beckett expressed it, could be a structural question in the composition of any painting. Figures, of necessity, must be located somehow or other in space. But Watteau’s methods, splicing his theatrical scenarios together from disparate sketches, lent the conjunction a new self-consciousness. A bower in a painted backdrop, an avenue in some Paris mansion’s garden, statues in the park of a château: Weren’t they all equally arbitrary, equivalently unreal? Perl describes the implications:

There is a sense in which every painting is a kind of stage, and Watteau explored this dimension of painting as thoroughly as any artist who ever lived, until the framedness of the painting, the forcefulness of the rectangle, was capable of sharpening, accenting, italicizing the meaning of the most casual human behavior.

Reaching for that epithet “italicizing,” his criticism is at its nimblest. Always ready to deploy old-fashioned formalist analyses, Perl here uses them to suggest an exact and startling metaphor for the Watteau figures such as that blonde with her back to us. Yet maybe there is also a social aspect here that he does not investigate. A small-town boy come to the big city, with the theater scene as his one sure foothold, is giving us a wry, equivocal response to the spaces that city sets aside for its amusements, with their ornamental and nearly functionless versions of “nature.” Watteau becomes “modern” also in evoking this sense of suburban leisure: the organic descendant of The Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera, with its holiday dalliances, its dandyism, and its vaguely busked backdrop, is arguably Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Cythera is never merely Saint-Cloud, just as Manet does not tie us down to the Bois du Boulogne, yet in each case the image’s keen arresting edge surely stems from specific local stimuli.

The human mind is artless, elegant, clumsy, penetrating, chaotic, obscure, a hopeless mix of serenity and hysteria, the lofty and the low-down, clarity and murk, and Watteau pulls his drawings and paintings straight out of this messy material, these moment-to-moment shifts in perception, apprehension, and feeling. His paintings suggest a mind that is, like all our minds, at once self-indulgent, unreliable, relentless, lucid, obtuse, unruly. And like the rest of us he allows his thoughts to drift, his moods to shift, his focus to go out of focus.

This bluster has a kind of bravado, but it’s facile. Anyone can zap the totality of the mind with adjectives and then refine the resulting splatter of truisms until it delivers something loosely germane to a certain artwork. Perl’s piece on The Pilgrimage goes on to discuss the pastoral tradition that informs it (he’s good on such art-historical themes), to analyze the composition’s “powerful undulating lines,” and to quote the Goncourts’ encomia at their lushest. Nowhere, though, does he bring us close to Watteau himself at work. I don’t need to be reminded that this image is in the highest degree magical; I want to learn something of what it can have been like to paint it. Perl does not seem interested in telling me.

One of the limitations of his Alphabet —for all that it’s as lively as anything written on the artist since Watteau’s friend the Comte de Caylus penned a sharp little memoir back in 1748—is that Perl doesn’t wholly think his way into the paint on the canvases. It seems a strange blind spot, but perhaps it’s strategic. As I’ve mentioned, Perl declares in the prologue that Watteau is his favorite painter. He then adds that whenever he reveals this passion of his, people seem surprised. He supposes they’d prefer him to nominate “Rembrandt or Goya, or some other figure whose work has a certain darkness about it.” Maybe, he later speculates, they can’t get on with Watteau’s sense of color; and he counters that prejudice with a poetic, indeed highly persuasive defense of the subtle “disunity” of his palette.

But this is to evade the obvious reason why Watteau makes an unlikely candidate for number one painter: that for all the poignant originality of his vision, he is a fairly uneven handler of the brush. Always he is translating a three-crayons technique of sketching, at which he truly is a master, into an oil medium that evidently pleases him less. Deft with satins, punctilious with faces, he contorts himself when it comes to hands, while his renderings of nude bodies slither and bodge, unsure what to treat as contour and what as fleshly expanse.

Caylus wrote, very believably, that his friend’s dissatisfaction with his own work arose from being “in the situation of a man who thinks better than he acts.”5 Behind the purveyor of the little fêtes galantes lay a truly ambitious student of Rubens and the Venetians who only fully came into his own in three or four large late canvases. That important issue of scale gets rather elided in Antoine’s Alphabet, along with other specifics of facture. The prose skates briskly away from the paint surface, abstractly glancing at its blends of “velvetiness and steeliness” and of “insouciance and seriousness.” The charming ancien régime engravings by Watteau chosen to illustrate the volume do nothing to acquaint the reader better with the physical facts. Rather than objects, the book deals in images; rather than brushmarks, it turns toward reveries.

A will to romance, in fact, is the other burden that dogs the project. Perl does not simply write out of love, he writes with a determination to emote. He chases after Watteau’s elusive belles, “goddesses on the lam”; he has the artist invite one of their number to “join him in the dance of life, dancing oh so slowly, as the world passes by”; verbally, he caresses that feminine ideal: “alone in her bed, her flesh shimmering like jewels on dark velvet.” He draws up party lists, conceiving “a Parnassus where all the daydreamers meet.” Giorgione and Bonnard are gathered in that garden; Verlaine and Wallace Stevens, “the poets who love the commedia”; Schoenberg with his Pierrot Lunaire ; Nijinsky and Baryshnikov; Matisse, “accompanied by a gorgeous young woman who’s wearing the Harlequin dress, beautifully crafted, that he likes to have his models try on. And let us not forget Picasso….”

At such moments I hear not so much a sentimentalist in paroxysms as a self-possessed commentator dallying in a devil-may-care fashion with his capacity to exasperate. Mischief is a vein that courses right through this captivating, stimulating, and occasionally foolish venture—mischief springing from the diversionary instincts of a generation of Parisians weary of a patriarchal regime, and issuing here in the faintly incorrect daydreams of a critic turning aside from a frustrating art world. Is Antoine’s Alphabet a little precious? It is hardly pretentious. It is one man talking quite democratically with others about the pictures that happen to stand before them, pictures whose ambiguities run to the root. Those fringe theater troupes from whom Watteau drew so much of his material were pestered by constant official restrictions. For several years their actors were not even allowed to speak on stage; and so they put up placards, inviting the spectators to supply the speeches instead.6 The custom has been gracefully reanimated.

This Issue

February 12, 2009

-

1

The most comprehensive one-volume source for facts about Watteau is the catalog of the 1984 exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., Watteau: 1684–1721, edited by Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Pierre Rosenberg. This contains François Moureau’s illuminating essay ” Watteau in His Time,” on which I particularly draw. ↩

-

2

The possible political implications of the imagery of “Cythera” are explored in a challenging new study by Georgia J. Cowart. Her book, The Triumph of Pleasure: Louis XIV and the Politics of Spectacle (University of Chicago Press, 2008), addresses the cultural dynamics of a reign that lasted from 1643 to 1715, focusing in detail on the music of Jean-Baptiste Lully and the dramaturgy of Molière. In her final chapter, Professor Cowart proposes an ideological interpretation of Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera, tying it to the freethinking or “libertine” school of thought that had been repressed under Louis. She will curate an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, “Watteau, Music, and Theatre,” this September. ↩

-

3

The quotation is from P.-N. Bergeret, Lettres d’un artiste sur l’état des arts en France (Paris, 1848). It is cited in the previously mentioned catalog Watteau: 1684–1721, p. 398. ↩

-

4

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, “La Philosophie de Watteau” (1856), quoted in Donald Posner, Antoine Watteau (Cornell University Press, 1984), p. 7. ↩

-

5

Comte de Caylus, “Life of Watteau,” as translated by Robin Ironside in Art in Theory, 1648–1815: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, edited by Charles Harrison, Paul Wood, and Jason Gaiger (Blackwell, 2000), p. 360. ↩

-

6

This is described in the above- mentioned essay by Moureau, “Watteau in His Time,” in the catalog Watteau: 1684–1721, p. 486. ↩