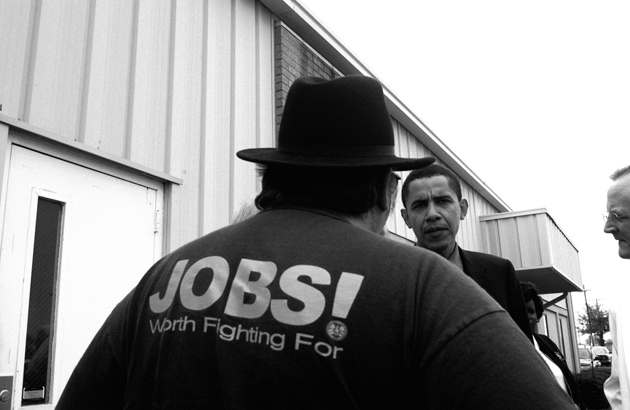

Jeff Madrick’s The Case for Big Government arrives when one might imagine that Wall Street has made the case quite persuasively on its own. By mid-February, the Federal Reserve’s once-gargantuan $29 billion rescue of Bear Stearns had been dwarfed not just by the government’s hotly debated $700 billion “bailout bill” last fall, or even President Obama’s nearly $800 billion stimulus package, but far more stunningly by the $7.6 trillion the Fed and Treasury had by the beginning of 2009 already pledged to contain the ever-widening collapse of the economy, and the additional sum of up to $2 trillion that the new administration said it would raise from public and private sources to rescue banks. Governments from London to Beijing have meanwhile rushed to provide vast sums to their own capital markets.

These figures are mind-numbing to voters—and to sophisticated investors and economists as well, and for good reason: fifty years ago the United States spent what in today’s dollars would amount to only $115 billion on the Marshall Plan to reconstruct all of Western Europe; the 1980s savings and loans bailout—at the time the largest financial rescue operation since the Great Depression—cost taxpayers a mere $130 billion. But while bailing out the financial system should urgently concern us, Madrick argues, what is fundamentally needed is a different conception of the role of government.

In the midst of this crisis, one can make cases for three very different kinds of “big government.” The first is the rescue of Wall Street, an immediate but temporary intervention, already in play; the second is for government to act as a general contractor in the economy’s reconstruction—the medium-term investment in infrastructure, from roads to schools, that Obama is now unveiling in his “recovery plan.” But the third possibility, which is the central concern of Madrick’s book, has not yet been the subject of serious public debate: to use government as long-term guarantor of America’s (and indirectly the world’s) economic stability, as provider of widespread opportunity, and as partner with the private sector in restoring long-term stable growth. Madrick, in a nuanced and wide-ranging fashion, makes the case for that third approach.

The book’s logic runs something like this: at the heart of the US government’s economic policies since the Nixon administration is a set of arguments that may cripple Obama’s ability to carry out more ambitious reforms, and has, in Madrick’s well-documented view, already damaged the well-being of most Americans when their lives are compared to those of previous generations and to citizens of other well-to-do countries. These arguments deride the idea of “big government” in any form, and are widespread and deep-rooted in our history; those who make them are well financed, often fiercely ideological, and committed to resisting policies that aim to increase the role of government in the social and economic life of the country.

“Market-based solutions,” in this new conventional wisdom, have become—for every Republican and Democratic administration since Jimmy Carter deregulated the airlines—the mantra for solving the big public policy issues of our times. Ronald Reagan, guided by such economists as Milton Friedman and Arthur Laffer, declared government “the problem, not the solution,” but it was Bill Clinton a decade later who, prodded by Robert Rubin and the Democratic Leadership Council, proudly announced that “the era of big government is over” before going on to back legislation for a balanced budget, welfare reform, and an ever-declining public workforce.

Leaders who have endorsed this bipartisan consensus running from the right to the center left don’t always agree fully on particulars, but tend to share a uniform enthusiasm for “market-based solutions,” whether the deregulation of transportation, utilities, telecommunications, and finance; the privatization of services from trash collection at home to security services in Iraq, as well as retirement savings and investment; the provision of vouchers for education and health care; or so-called cap-and-trade solutions to issues of the environment such as global warming.

How and to what degree such “market-based solutions” will end up influencing the Obama administration is much debated. So far the members of his economic team have not reassured some of his more progressive supporters. Announced by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner on February 10, for example, the administration’s strategy for the banking crisis includes the establishment of a Public Private Investment Fund, or “bad bank,” to buy up and hold as much as $1 trillion in bad assets, as well as further capital injections in banks and a vast expansion of a lending program to finance student loans and consumer debt. But it does not go as far as some economists would like in imposing conditions on the financial sector of the economy. Together with Geithner, the appointments of Lawrence Summers as head of the National Economic Council, Jason Furman as his deputy, Austan Goolsbee on the Economic Recovery Advisory Board, and Christina Romer as chair of the Council of Economic Advisers have collectively prompted disquiet among such economists as Robert Reich and Paul Krugman, even as their selection reassured capital markets—however unevenly and briefly.

Advertisement

Madrick himself is not a declared political partisan. He is a former economics columnist for The New York Times, the author of several well-regarded books on contemporary economic policy, and he writes frequently in these pages. During the past decade, he has grown increasingly alarmed about the direction of economic theory and policy, and he puts forward large-scale alternatives for government action. But his goal here is not to persuade conservative commentators such as George Will or disciples of Milton Friedman, but rather journalists, academics, policy intellectuals, and politicians who have embraced the earlier “public marketeering” consensus—as well as members of a younger generation who may be unfamiliar with past achievements of government and the potential of the public sector.

Madrick first provides a short history—a primer, really—of government’s often-forgotten but central role in the nation’s long economic rise from the 1770s to the 1970s. He then assesses how the economy, the nature of competition, and living standards have changed over the past thirty years. Although he completed his book last summer before the scope of the current collapse became visible, he concludes that there are deeply worrisome signs of a sharp and accelerating deterioration in the quality of American life. The book closes with a prescriptive essay, “What to Do,” in which he outlines how the federal government could substantially increase current revenues, and where to spend them to greatest long-term effect.

The book’s opening historical essay reminds us that from the American Revolution to the Great Depression, government’s share of GDP—that is, federal, state, and local public spending as a proportion of the nation’s total income—was quite small. It was probably about 1 or 2 percent in 1800, and 7 to 8 percent a century later. Yet its influence was disproportionately large for several reasons. First, upon organization of the Northwest Territory in 1789, the federal government became the nation’s largest landowner—a fact not reflected in conventional GDP calculations. And over the next century and a half the federal government was able to shape economic growth through its land distribution policies: for example, it used sales and leases of its land to foster small-scale farming, promote free primary (and later higher) education, encourage forestry and mining, and finance the nation’s vast transportation network.1 Second, state and local governments from the beginning of the Republic actively promoted large-scale investments in infrastructure, notably in roads and canals, and subsidized America’s primary education system, which made the young nation the most literate in the world—an enormous advantage in utilizing the new technologies on which mass production was founded.

Between the Civil War and World War I, moreover, governments at the federal—but especially the state and local—level all steadily expanded their regulatory powers to meet the challenges posed by the surging immigration, urbanization, and industrialization that made the United States the world’s largest economy by the 1890s. Although primarily at state and local levels initially, government intervened actively and repeatedly in matters of business organization, consumer rights, working conditions, new technology, utilities, public health, agriculture, urban design, and private and public finance.2 Particularly impressive, for example, was the construction of large-scale sanitation systems in cities throughout the nation.

As Madrick makes clear, the effect of all this government intervention was to enhance the country’s overall rate of growth even as it helped equalize income and wealth distribution. Government legislation helped create an educated workforce and build crucial infrastructure, guaranteed enforceable contracts, reduced corruption, opened new markets domestically, sponsored scientific and technological research and development, and globally, through expanded trade agreements and gradually reduced tariffs, made America an international economic giant.

The Great Depression began a substantial shift from a predominantly regulatory state to a revenue state. The public’s demands for economic security meant that government would need to invest large amounts of money in the economy to assure stability and near-full-employment growth. In consequence, the government’s 7 to 8 percent share of GDP at the start of the century tripled over the next fifty years. As Madrick explains, our vastly overheated debates about today’s “big” versus yesterday’s “small” government rarely focus on that simple fact: since the late 1950s, American government —federal, state, and local—has annually spent approximately 30 percent of GDP, and neither Democrats nor Republicans have altered that by more than a percent or two, upward or downward. Indeed, the size of government, as a share of GDP, reached its greatest extent since World War II not under Kennedy, Johnson, or Clinton, but under Ronald Reagan, and on average has been higher under Republican presidents. (Long the champion of “fiscal responsibility,” GOP presidents since Eisenhower have not been able to balance the federal budget.)

Advertisement

Having carefully established the long-running and generally beneficial effects of “big” government, Madrick turns to the intellectual claims of figures such as Milton Friedman, whose work was central to creating the new “small government is better government” consensus. In fact, Madrick writes, the Chicago economist “offered much ideology but little evidence” that big government undermined economic growth. Friedman claimed in the 1970s that the corrosive rate of inflation at the time was caused by rising public spending and the growth of the money supply. In reality, however, the government’s share of GDP didn’t rise during this time, and far larger budget deficits under later Republican presidents produced no noticeable increase in inflation. International comparisons likewise have shown that big government does not undermine a nation’s ability to produce more efficiently. Citing the economist Peter Lindert, who spent years compiling his data on the effects of the welfare state on economic growth, Madrick writes that there is a stark “conflict between intuition and evidence” on this topic. As Lindert wryly observed, “It is well-known that higher taxes and transfers reduce productivity. Well-known—but unsupported by statistics and history.”

Madrick, like everyone else, recognizes that corrupt and inefficient governments, of whatever size, damage not only growth but freedom. But he presents persuasive evidence that

big or small government is not the critical criterion in economics. To the contrary, government’s management of change is what is critical. And government is a key and arguably the main agent of change…. In the laboratory of the real world, the governments of rich nations have on balance been central to economic growth, and in the process have retained their citizens’ faith in their nations’ promise and social values…. If what we think of as big government is necessary to manage change, and in a complex society it may well be, then we should pursue it actively and positively, and make it function well.

Among the rich nations of the world, he points out, there really haven’t been any “small” governments for nearly a century. Among the wealthy OECD countries, for example, the public- sector share of GDP averages roughly 40 percent (the US’s 30 percent is the lowest of the group). It is no coincidence, in Madrick’s view, that the US leads the OECD in income and wealth inequality, poverty, crime, hours worked, and infant mortality.

Since the 1970s, Madrick shows, the US economy has grown more slowly than in the thirty-year period after the end of World War II, but also very likely more slowly than in any other period in the nation’s history. For many years economists attributed this reduced growth to a difficult-to-explain slowdown in business productivity. But as Madrick points out, even after productivity growth returned in the mid-1990s, average wages—which had stagnated for twenty years—continued to stagnate. In fact, between 2001 and 2007, wages grew not at all, something unprecedented in any previous recorded business recovery.

In the second section of his book, Madrick points to a number of by now familiar changes that have occurred in the last three decades. The percentage of women in the workforce has grown dramatically. Manufacturing has declined precipitously; and health care costs have tripled as a share of GDP (and now exceed manufacturing’s share). Consumer, business, and government debt have all soared. Household debt, for example, has risen from fifty cents per dollar of family income to $1.20 per dollar. The federal government’s total debt over the same period doubled from a third to two thirds of GDP. At the same time, the social safety net, public and private, has deteriorated badly, not only for the poor but for the middle class and even parts of the upper-middle class. Pension savings are now largely the responsibility of individuals, health care premiums are rising much faster than the overall cost of living, higher education costs have soared, and mortgage payments have reached an all-time record, measured as a share of household income.

Two of the most critical factors behind these fundamental shifts, according to Madrick, are the changing distribution of income between men and women and the changing distribution of income by education. From the 1970s onward women have modestly narrowed the wage gap with men, although the gap is still wide. The nature of that differential, however, has changed: in fact women’s gains have come in part because of a perverse convergence. Wages for men have been deteriorating at the same time that women’s wages have been rising. Among women, all income levels have made some progress, but below the top 10 percent of female earners, the progress has been much more slight.

Among men, the effects of stagnating income have been felt especially by those without a college education, although even men with college educations have not fared well. The median hourly wage for all males has actually fallen since the 1970s—unprecedented in American history—while the income for college-educated males has risen barely 10 percent, also a new historical low.

The fact that so many women work has, while closing the gender earnings gap, ironically contributed to widening inequality among families—especially between households with two high-earning workers and those with a single median- or minimum-wage earner. For historical comparison, the average family income between the end of World War II and 1973 doubled, in inflation-adjusted terms. Since then, the gain among two-parent families has risen only slightly (and almost entirely during Clinton’s second term). After George Bush took office, there were modest gains only for families with two workers; for families with one earner, there was no gain whatsoever. As Madrick bluntly summarizes:

Families now work longer hours—about two and a half or three months a year more of work on average. They often live farther from work, thus spending more time commuting. Kids must take longer to finish college, and borrow much more to pay their way. Two-worker families have new expenses that are rarely included in the data, such as a good second car, baby-sitters, take-out food, and cleaning help. Good full-time infant care can cost $2,000 per month in major urban areas. People have to move to expensive neighborhoods because the schools are better, and they take on large mortgages. Debt is way up as a result….

Are we now jeopardizing the equality of opportunity because people cannot afford…good education, good health care and…good access to jobs and careers? Is the broad, positive definition of freedom, as discussed by Wilson, Roosevelt, and Johnson, and I would argue Jefferson and Lincoln, under assault? In the process, are individual rights under assault as well?

In the final part of The Case for Big Government, Madrick outlines what he believes should come next. It is not merely a matter of policy reform, or shifting leadership from one party to another. Instead, he argues, we need to rediscover Americans’ capacities for transformational change and the way “big government” can help achieve that end:

How did the wealthiest nation in history come to believe it is not wealthy?…

America has no free and high-quality day care or pre-K institutions to nourish and comfort two-worker families…. College has become far more expensive and attendance is now bifurcated by class…. Transportation infrastructure has been notoriously neglected, is decaying, and has not been adequately modernized to meet energy-efficient standards or global competition. America has not responded to a new world of high energy costs and global warming in general. America has a health care system that is simply out of control, providing on balance inadequate quality at very high prices…. The financial system, progressively deregulated since the 1970s, broke free of government oversight entirely in the 1990s and early 2000s and speculation reminiscent of the 1800s was the result with potentially equal levels of damage…. These facts amount to about as conclusive a proof as history ever provides that the ideology applied in this generation has failed.

Madrick calls for new spending programs and new ways to raise revenue to reverse the consequences of failed ideology over the past three decades. These recommendations provide a useful benchmark by which to assess the Obama administration’s current and coming proposals, although the financial crisis has already redrawn the landscape of the possible.

For example, Madrick argues cautiously for an annual $400 billion increase in public spending overall. This would roughly increase government’s GDP share by a modest 3 percent, close to the original stimulus package Obama submitted to Congress (since the $800 billion the President proposed is designed to be spent over the next two to three years, not one). The full implications of the House–Senate compromise on the President’s spending and tax- cut program remain to be examined, as do other administration proposals. But comparison with Madrick’s recommendations is illuminating.

In the case of health care, for example, it seems unlikely that Obama will support the kind of single-payer system advocated by Madrick. Nor should we expect anytime soon the new president to advocate, as Madrick does, public financing of elections, in view of the extraordinary fund-raising prowess he showed in reaching the White House. Unlike the stimulus package, Madrick also does not advocate major new tax cuts (although he might now, as a temporary counter-cyclical measure).

When it comes to public spending on infrastructure, however, Obama has already announced an ambitious plan that echos Madrick’s emphasis on a “green,” jobs-creating investment strategy (although important details may be very different, reflecting the legislative alliances he needs and the persuasive power of lobbyists). Likewise, Madrick’s and Obama’s proposals for reregulation of finance, a more progressive tax system, increased funding of education at all levels, and large funding for transportation reform all have much in common. It isn’t yet clear whether the policies Obama gets through Congress on trade, globalization more generally, and ways to reequalize income and wealth will converge with Madrick’s. The full shape of the President’s own proposals, and what politics makes of them, remains to be seen.

The book’s largest flaw is that it is not as careful and clear-eyed politically as it is economically. The Case for Big Government usefully takes aim at the ideological consensus that emerged among many academics, journalists, policy advisers, and politicians in both parties. But it devotes little attention to the rise of religious fundamentalism that coincided with America’s industrial decline, and how the departure from the Democratic Party by millions of white Southern evangelicals and Northern, mostly Catholic, industrial workers—twin pillars of the New Deal—contributed to the world we face today. In many ways this shift may have been more consequential to the spread of “small government” ideology than the intellectual realignment of academics, journalists, policy advisers, and politicians.

The book also ignores the effects of American foreign and military policies on economic growth. Between 1945 and 1975—the period Madrick cites so approvingly in contrast to the decades that followed—half of all federal spending was for the military, and significant parts of the rest (including for education, roads, science, and technology) were justified as military preparedness. One cannot know when and how the situation in Iraq will end, or whether the war in Afghanistan will grow far larger and more costly—but analysts such as Madrick might consider the effects of the Vietnam War in helping to destroy the New Deal consensus.

Still, Madrick is correct to argue that most Americans—congressional Republicans and broadcasters such as Rush Limbaugh notwithstanding—seem ready to move past the thirty years of conservative domination that resulted from increasing distrust of government. The dismal failure of deregulated financial markets has now—just as in the 1930s—forced upon the US the most fundamental and costly sorts of public interventions in markets. The extent to which Madrick’s insightful and persuasive arguments will be taken up in US policy now rests to a large degree on whether President Obama and the Democrats can restore America’s basic financial health. For the time being that means concentrating on government’s ability first to save Wall Street and restore credit, and then to begin rebuilding the devastation Wall Street’s failure has left behind. The challenge of creating a new era for government as long-term guarantor of our security and well-being lies ahead.

—February 12, 2009

This Issue

March 12, 2009

-

1

Government—federal, state, and local —still controls nearly 40 percent of all the land in the country. See www.nrcm.org/documents/publiclandownership.pdf ↩

-

2

Morton Keller’s Regulating a New Economy: Public Policy and Economic Change in America, 1900–1933 (Harvard University Press, 1990) and Regulating a New Society: Public Policy and Social Change in America, 1900–1933 (Harvard University Press, 1994) provide an overview. ↩