A perturbation arising from the American market in subprime mortgages has spread through the banking system to disrupt economic activity throughout the world. The pattern of cause and effect will be debated for many years, with historians asking when and how the global economy was set on the path that led to its current condition. Already there are some who trace the crisis to decisions of Alan Greenspan, chairman of the board of governors of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006, when he responded to events such as the collapse in the late 1990s of a hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management, and the subsequent bursting of the dot-com bubble by creating a climate of easy borrowing, which in turn inflated another bubble in the housing market.

Others suggest that a change in the legal system of banking brought about by the repeal in 1999 of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which had aimed to limit speculation by separating commercial and investment banking, created an environment that allowed reckless lending. Yet others explain the turmoil in world markets as a symptom of an endemic instability in the type of finance capitalism that has developed in America, Britain, and some other Western countries.

These accounts are not mutually exclusive, nor are they in any way exhaustive. Like most of the narratives that offer to tell us how the world arrived at its present pass, they are primarily economic in focus. To be sure, this is an economic crisis; it might therefore seem to follow that it is best explained in economic terms. But economics may not give a satisfactory understanding of the events of the past year. The changes that have occurred are not only in the world economy. They include shifts in geopolitics, involving aspects of the rise and fall of nations that go beyond their economic performance, and an erosion of values.

The dislocation that is being produced by the financial crisis affects political and moral beliefs that have supported capitalism in the past. Market economies are not underpinned chiefly by economic theories. They rely for their legitimacy and continued functioning on ideas about right and wrong, fairness in society, and orderliness in the world. In the boom years many of these ideas were discarded as erroneous or redundant. Now that the boom has been followed by bust it may be useful to reexamine ideas about debt, and consider how they may fare as governments use all the instruments at their disposal to avert a slide into depression.

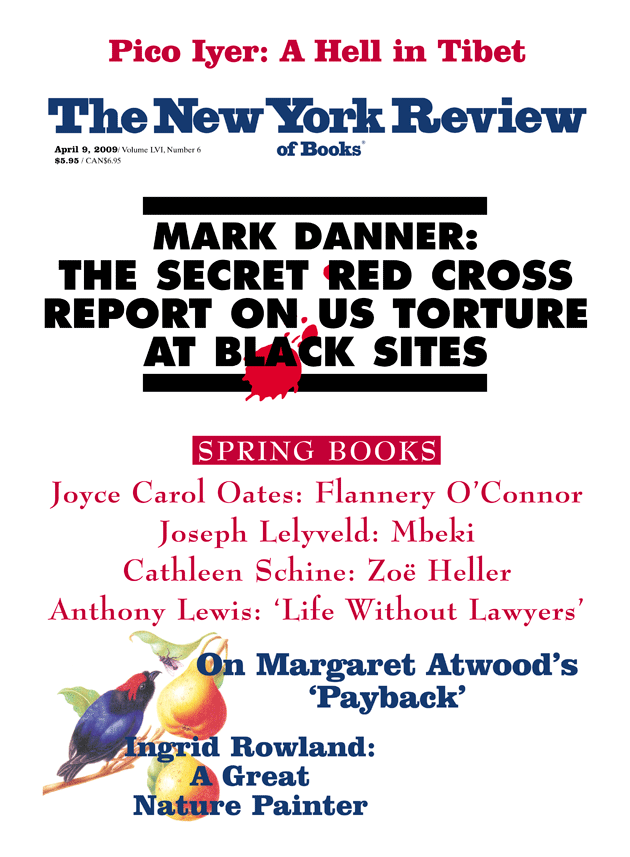

One of the many impressive features of Margaret Atwood’s new book is its almost eerie timeliness. Consisting of five chapters that were broadcast in November 2008 by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as the Massey Lectures, a series intended to provide a radio venue for the exploration of important issues, Payback appeared in print last October. The book must have been written some months earlier, but there is no sign that it was composed in haste. Atwood examines the role of ideas of debt in religion, literature, and society; she discusses the nature of sin, the structure of plot in fiction, the practice of revenge, and the ecological payback that occurs when human beings take from the planet more than they return. A celebrated novelist, poet, and critic, Atwood has combined rigorous analysis, wide-ranging erudition, and a beguilingly playful imagination to produce the most probing and thought-stirring commentary on the financial crisis to date.

Atwood’s project is to show how human thought has been deeply shaped by notions of debt. It will be objected that she is merely spinning out an extended metaphor suggesting analogies between debt and noneconomic phenomena that are only vaguely analogous. In fact she is advancing the contrary and more interesting claim that economic activities involving borrowing and lending are metaphorical extensions of an underlying human sense of indebtedness. Beliefs about debt are not shadows cast by processes of market exchange. They are presupposed throughout much of human activity. Economic life invokes a sense of order in human affairs, widely dispersed throughout society.

A sense of what one is owed does not seem to be confined to humans. Atwood cites the primatologist Frans de Waal, who found in a series of experiments that capuchin monkeys that had been trained to trade pebbles for slices of cucumber threw their pebbles out of the cage and refused any further cooperation with the experimenters when one monkey was given the more valuable prize of a grape in return for a pebble. If an ability to assess what one is due seems to be present in some of humankind’s closer evolutionary kin, among humans it is universal. The ancient Egyptian notion of ma’at, Atwood writes,

meant truth, justice, balance, the governing principles of nature and the universe, the stately progression of time—days, months, seasons, years. It also meant the proper comportment of individuals toward others, the right social order, the relationship between the living and the dead, the true, just, and moral standards of behaviour, the way things are supposed to be—all of those notions rolled up into one short word. Its opposite was physical chaos, selfishness, falsehood, evil behaviour—any sort of upset in the divinely ordained pattern of things.

In this ancient Egyptian conception, balance in human affairs is linked with order in the natural world.

Advertisement

In Christianity the relationship between humankind and the divine is represented in terms of borrowing and lending:

Christ is called the Redeemer, a term drawn directly from the language of debt and pawning or pledging…. In fact, the whole theology of Christianity rests on the notion of spiritual debts and what must be done to repay them, and how you might get out of paying by having someone else pay instead.

Sociologists have observed how capitalism developed using ideas borrowed from religion, with Max Weber and others observing how the belief that wealth creation is virtuous invoked Protestant ideas about an elect, divinely privileged section of humanity. As Atwood astutely comments, the conceptual traffic is not just one-way. If economic life trades on religious belief, religion has in turn been shaped by market practices. Religious beliefs about sin and redemption draw on patterns of thinking that partly derive from the practices of borrowing and lending.

Concepts of debt figure centrally in Western religion, while the notion that debt is something to be avoided, or incurred with caution, has long been important in Western capitalism. Without institutions facilitating borrowing, capitalism would not have developed to the degree that it has; but the belief that debt could be dangerous was until recently also an important part of capitalism. It is only lately, Atwood notes, that debt has been celebrated as positively benign, “a thing we’ve come to feel is indispensable to our collective buoyancy.” From being a necessary tool in productive enterprise, debt came to be viewed as an instrument of wealth creation. Using cheap credit, hedge funds and investment banks were able to multiply their profits, while society at large—including some in its poorest groups—came to see taking on large amounts of debt as a way of building up capital. Now that this structure of debt is unwinding, older ideas may be on their way back: “We seem to be entering a period in which debt has passed through its most recent harmless and fashionable period, and is reverting to being sinful.”

From one angle Payback can be read as a defense of traditional beliefs about the hazards of debt. Atwood recalls the cautionary lessons she was taught at Sunday school in the 1940s and recounts how her mother kept an account book for fifty years, which records that “debts were always paid back within a few weeks, or a few months at the latest.” What she describes as “snake-oil debt” undermined these practices. Being in debt came to be seen as an entirely normal condition. It was debt rather than current income or past savings that sustained consumption and enabled people—here Atwood is talking mainly of Americans, though the same is true in Britain—to enjoy the standard of living to which they had grown accustomed. The credit crunch began when some among them were persuaded to incur debts they had no prospect of repaying, debts that were packaged and sold on in complex financial instruments that few of those involved in the transactions fully understood.

Implicit in Payback is the notion that we may now be returning to older and simpler practices of thrift and saving, and there seems little doubt that Atwood would welcome such a shift. Yet it looks unlikely that these old-world virtues will be rewarded in the foreseeable future. In the US, Britain, and countries throughout much of the world, the drift of policy is to stimulate borrowing by reducing its cost to as close to zero as is practicable, while expanding debt-financed government spending on a large scale. At the same time central banks are moving toward policies of “quantitative easing”—buying government bonds and other assets in order to increase the supply of money and reenergize economic activity, so that society can in effect borrow itself out of debt.

Policies of this sort resemble the proposals advanced in the 1930s by John Maynard Keynes to deal with the Great Depression. Keynes argued that whereas paying off debt in hard times may be reasonable for individuals, it may be irrational for governments, further depressing the economy and increasing the burden of borrowing. Whether Keynes, an extremely subtle and many-sided thinker, would approve of the policies that are being applied today cannot be known. What is clear is that these policies render traditional attitudes toward debt and saving by individuals imprudent. Their goal is to encourage people to borrow more and spend more, and so return the economy to the debt-financed consumption of recent years. Underlying this objective is another—to avoid the danger of debt deflation, the lethal combination of falling asset prices with high borrowing that helped bring about the Great Depression.

Advertisement

Critics often argue that these policies risk sparking inflation at some point in the future. In fact they can hardly be expected to work unless they have this result. Inflation is a sure-fire way of lightening the debt burden, and much of the debt that was contracted in the boom years can probably be paid off only in devalued dollars. But this involves a transfer of wealth from savers to borrowers: those who have borrowed unwisely will benefit, while those who have saved prudently will see their wealth dwindle in value. “Keynesian” policies can succeed only insofar as they have this effect; their impact will be reduced to the extent that people revert to traditional practices of thrift and saving.

From one point of view this is an illustration of a familiar divergence between general welfare and distributive justice. A measure of unfairness is often the price of achieving important objectives. European countries such as the UK that have systems of socialized medicine routinely use cost-benefit analysis to ration scarce and expensive medical resources—MRI scans, for example—a procedure that can involve denying these resources to some who might wish to have them, but that is commonly accepted as justified. The difficulty in the present case is that the unfairness is likely to be far-reaching and intensely felt.

Large sections of the population could find their wealth—already depleted by the decline of the housing and stock markets—shrinking further as the value of money is reduced, while much of the baby boom generation may discover that the comfortable retirement they expected has become an unrealizable dream. In present circumstances there may be no alternative to current policies. But a necessary condition of their effectiveness is a disappointment in reasonable expectations that could be socially disruptive.

In a fascinating chapter, Atwood discusses the role of debt “as a governing leitmotif of Western fiction.” Particularly in nineteenth-century novels, but also in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, incurring debts of one kind or another formed a major plot line. Debt meant more than having an obligation to discharge; it was central to the stories people told of their own and others’ lives. It has a similar role today. When it becomes clear that debts cannot be paid off, it is not just that people may walk away from them—as many who were induced to take on subprime mortgages have been doing. Their trust in the society that encouraged them to incur the debts is also destroyed. Again, the shock that is felt when a major part of a lifetime’s savings vanishes, seemingly overnight, does not come only from the prospect of a diminished standard of living. It comes also from the collapse of the narrative according to which people have hitherto understood their lives.

These dangers may not materialize if economic growth is quickly resumed. But there are formidable obstacles in the way. The world’s largest debtor country, the US, is heavily reliant on China purchasing its government securities. Without the influx of Chinese capital American debt would not have reached its current level, while American living standards would have been lower. In effect China has helped fund the federal deficit, and thereby reduce the cost of credit, in return for an assurance of open markets for its goods in the US. Since this arrangement has been mutually beneficial in the past and the costs of abruptly terminating it could be severe for China as well as the US, most economists have assumed that it will continue in the future. This may underestimate noneconomic factors in Chinese policymaking. If the global downturn is severe, China’s rulers, moved by fear of popular unrest and political instability, may divert their surplus to domestic use regardless of the impact on US finances.

Again, economic self-interest may be less significant in shaping Chinese policies than the geopolitical opportunity that is presented by fast-waning American hegemony. Not only America’s standard of living but also its high level of military expenditure relies on China allowing the US to live beyond its means. There is no reason to suppose that China will always be so willing. In any case it will not be the US that decides whether the relationship it has enjoyed with China continues. It is China that is the rising power, and borrowers on the scale of America in recent years cannot expect to be choosers.

There is another, larger obstacle to restoration of the American economy. The level of consumption achieved in America in recent decades did not depend only on a high level of borrowing from China. It also involved running up a large debt to the planet. In the last chapter of Payback, Atwood imagines an amusing and enlightening dialogue between a latter-day Scrooge—“Scrooge Nouveau,” a self-centered hedonist who believes he owes nothing to anyone else—and “the Spirit of Earth Day Past.” The Spirit’s message to Scrooge is that there are limits to the expansion of production, consumption, and human numbers:

Mankind made a Faustian bargain as soon as he invented his first technologies, including the bow and arrow. It was then that human beings, instead of limiting their birth rate to keep their population in step with natural resources, decided instead to multiply unchecked. Then they increased the food supply to support this growth by manipulating those resources, inventing ever newer and more complex technologies to do so…. The end result of a totally efficient technological exploitation of Nature would be a lifeless desert: all natural capital would be exhausted, having been devoured by the mills of production, and the resulting debt to Nature would be infinite. But long before then, payback time will come for Mankind.

At the end of the conversation, which is also the end of the book, Scrooge Nouveau embraces the Spirit’s message:

I don’t really own anything, Scrooge thinks. Not even my body. Everything I have is only borrowed. I’m not really rich at all, I’m heavily in debt. How do I even begin to pay back what I owe? Where should I start?

Atwood puts into the mouth of the Spirit a “limits-to-growth” argument of a sort that is nowadays highly unfashionable. Contemporary evangelists of the free market, Marxian social critics, many religious fundamentalists, and most development economists are at one in believing that neo-Malthusian claims about the scarcity of resources are groundless; and that a mix of moral regeneration, institutional reform, and technological innovation can overcome natural limits to growth.

Yet Atwood seems to me to have the truth of the matter. Global warming as we observe it today is a byproduct of the industrial expansion of the past two centuries. A rapid resumption of the rate of economic growth of the last few decades—which is the aim of policymakers in the US and elsewhere—would increase the emissions of the greenhouse gases that are altering the climate. Along with political leaders in some other countries, President Obama speaks of “green growth”—promoting economic expansion by investing in environment-friendly technologies. But developing these technologies, putting them to use on a large scale, and reaping their benefits will take many years, while the need to avert depression is immediate and urgent. The likelihood must be that restarting economic growth by any available means will take priority over environmental concerns.

The effect of policies designed to lift the economy out of debt will be to increase the human debt to the planet. As demand recovers and growth resumes, the scarcities of resources that were becoming visible before the crash will return along with higher energy and commodity prices. Concern about the peaking of global oil supplies, which was widespread only months ago, has not become less well founded because speculators have been forced to unwind their bets on rising energy prices.

Most importantly, supporting a human population that, according to a consensus of estimates, will expand by around 50 percent over the next forty years will be an extremely daunting task in which it would be unwise to count on high levels of international cooperation. More likely, geopolitical competition for the control of the planet’s dwindling patrimony of natural wealth will intensify. At the same time the destruction of the biosphere, which along with rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions is an important cause of climate change, will accelerate. The result will be a hotter world that is less hospitable to humans.

If Atwood’s Payback contains a lesson it is that debts must be repaid. The type of political economy that operated in the US over the past twenty years, which some imagined would spread throughout the world, was based on the belief that this old-fashioned maxim no longer applied. A new era had arrived, in which sophisticated techniques of financial management could transform debt into a means of wealth creation from which even the poor could benefit.

The new era turned out to be short-lived, or else nonexistent. America was able to live on credit only by borrowing from other countries, above all China. With the bursting of the bubble it has become less clear whether America’s creditors will continue to commit funds on the required scale, while the claim of American finance capitalism to be a universal economic model has collapsed. Along with other governments, the Obama administration is faced with the task of dealing with the danger of recession turning into something worse. A large-scale monetary and fiscal stimulus will be administered in order to stave off depression. We must hope the stimulus has the desired effect. Whether or not it succeeds, it involves a redistribution from savers to borrowers that does not square with traditional values regarding the payment of debt. In order to resume economic growth, past debts will be devalued and new debts incurred.

That does not mean payback will be avoided. Returning to the levels of consumption of the recent past means running up an ever-larger environmental bill. As Atwood argues, there must eventually be a reckoning; the ancient conception of a link between human society and the natural world has not been rendered obsolete. If humanity is unwilling or unable to pay back its debts, the planet will surely collect.

This Issue

April 9, 2009