To the Editors:

In a review of Thomas Keneally’s Schindler’s List and Patricia Treece’s A Man for Others: Maximilian Kolbe, Saint of Auschwitz in the Words of Those Who Knew Him, John Gross claims that Father Kolbe’s papers “kept up a relentless anti-Semitic campaign” and quotes from an article Kolbe wrote in 1939 in which he refers to “international Zionism” as the guiding hand behind the “criminal mafia” of Masonry, which in turn was stoking the fires of “atheistic Communism.” While the reviewer stops short of charging, as the Wiener Tagebuch did in April, 1982, that Maximilian Kolbe was a “rabid racist anti-Semite,” and does mention that Father Kolbe did try to restrain his collaborators from attacks against Jews, Mr. Gross’s conclusion is of the same order.

The principal sources for Father Kolbe’s life and work, however, paint a quite different picture of the man: Gli Scritti di Massimiliano Kolbe, Eroe di Osiecim e Beato della Chiesa (3 vols; Florence: Edizioni Citta di Vita, 1975-1978) and Patavina seu Cracovien. Beatificationis et Canonizatonis Servi Dei Maximiliani M. Kolbe Sacerdotis Professi Ordinis Fratrum Minorum Conventualium (Rome: Sacred Congregation of Rites 1964), the former, the complete collection of Kolbe’s writings and sermons, the latter, some 940 pages of sworn eyewitness testimony. From these records it is clear that the Jewish question played a very minor role in Kolbe’s thought and work. Of his 1,006 extant letters and 396 other writings (newspaper and magazine articles, spiritual conference, etc.), only thirty-one refer to Jews and Judaism. Their content is overwhelmingly spiritual and apostolic with few comments of any kind on contemporary political, social, economic, or other secular concerns.

As Mr. Gross mentions, Father Kolbe’s main interest was his missionary work, in Kolbe’s words, “to seek the conversion of sinners, heretics, schismatics, Jews, etc., and, especially, Masons.” In this effort, “zeal” was always to be tempered by “prudence” and by respect for the individual. In 1926, he wrote that “Jesus died for each one of us without distinction, and that each of us, also each Jew, is always unworthy and is the son of our common heavenly mother” (Scritti, III, pp. 256-257).

Father Kolbe did, however, accept uncritically the picture of a Zionist-Jewish-Masonic conspiracy presented in the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, a work widely circulated in the Poland of his day. Thus, several of his mentions of Jews speak approvingly of the Protocols, and, as in the quote cited by Mr. Gross, one can find such phrases as “Jewish-Masonic conspiracy,” “cruel clique of Jews,” and “their work (the Talmud) which breathes hatred against Christ and the Christians.”

Yet, as on other issues, he warned against translating this image into social, political, or economic activism. Thus, in the admonition to his collaborators to which Mr. Gross is apparently referring, Father Kolbe states “speaking of the Jews, I would devote great attention not to stir up accidentally nor to intensify to a greater degree the hatred of our readers against them, who are already so ill-disposed or sometimes downright hostile in their confrontations” (letter to Father Marian Wojcik, editor of the Rycerz Niepokalanej, the monthly devotional magazine founded by Kolbe, Scritti, II, p. 183). Similarly, in a letter to his religious superior, Father Anselm Kubit written June 22, 1937, Father Kolbe describes a certain Monsignor Trzeciak as a “fiery anti-Semite to the point of being a chauvinist. Thus, the Maly Dziennik (a religious daily also founded by Kolbe) cannot follow his line and not all of his writings can find a place in the columns of the Maly Dziennik (Scritti, II, p. 323). Even in the 1939 article cited by Mr. Gross, Father Kolbe, after presenting the picture of a Jewish-Masonic conspiracy, goes on to state that “true scoundrels, those of evil intent, who sin with full awareness are relatively few.” Urging his readers to respond in a spirit of love and concern, he asks, “how can you not extend a hand to those people?” (Scritti, III, pp. 548-550).

The real test of Father Kolbe’s alleged anti-Semitism came at the outbreak of World War II when thousands of refugees were driven by the Nazis from western Poland. Numerous Polish witnesses have testified how Father Kolbe, himself just released from two-and-one-half months of German imprisonment and torture, sheltered all he could at his friary of Niepokalanow near Warsaw, without distinguishing between German or Pole, Christian or Jew (Polish estimates of the number of Jews cared for at Niepokalanow range from several hundred to more than two thousand). The refugees, Jews included, were given food, fuel, and clothing, and the sick were treated in the friary hospital. Kolbe frequently visited and consoled the refugees, without distinction of nationality or religion, even organizing a special New Year’s party for the Jews to balance the Christmas celebration for the Christians. Of particular note is the testimony of Rosalis Kobla, who lived near the friary. “When Jews came to me asking for a piece of bread, I asked Father Maximilian if I could give it to them in good conscience, and he answered me, ‘Yes, it is necessary to do this because all men are our brothers’ ” (Patavina, Seu Cracovien, pp. 389-390). Brother Juwentyn Mlodozeniec, who was at Niepokalanow at the time, quotes a certain Madame Zajac, a delegate of the Jewish refugees, as saying “in the name of all the Jews present here, we want to express our warm and sincere thanks to Father Maximilian and all his brothers” (I Knew Blessed Maximilian Kolbe, Washington, NJ: AMI Press, 1979, p. 53).

Thus, while Maximilian Kolbe shared some of the anti-Semitic stereotypes so widespread in prewar Poland, his image of the Jews, as of all who did not share his faith, was of people who were prisoners of error, not objects of hatred. Whatever theories he espoused, when he acted it was in a spirit of respect and charity, as his supreme sacrifice at Auschwitz showed.

Daniel Schlafly

St. Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Warren Green

St. Louis Center for Holocaust Studies

St. Louis, Missouri

John Gross replies:

Diana Dewar devotes several paragraphs to the question of anti-Semitism as it arises in connection with Father Kolbe’s prewar career as editor and publicist. They seem to me inadequate and in some respects evasive, but it is a measure of how completely Patricia Treece chooses to ignore the problem in her own book that one feels positively grateful for them by contrast.

That the problem is a very real one would surely be apparent from Daniel Schlafly and Warren Green’s letter alone. In the Poland of the 1930s it was no light matter for a man of Kolbe’s influence and stature to endorse the Protocols of the Elders of Zion or to indulge in the kind of language about “cruel cliques” and so forth which Messrs. Schlafly and Green quote; nor, of course, was it only a question of Kolbe’s own writings, but also of the general tenor of the publications which he founded and superintended. At a time of feverish anti-Semitism, hostile images of Jews, whether intended for purely theological consumption or not, were only too liable to get translated into “social, political, or economic activism,” often of the most brutal kind. (An excellent recent account of the plight of Polish Jewry during the years in question can be found in Celia Heller’s On the Edge of Destruction: Jews of Poland Between the Two World Wars, Columbia University Press, 1977.)

The Church was the one major institution in the Poland of the period potentially equipped to hold at bay the spread of anti-Semitic forces, but its actual record in this respect is, alas, far from exemplary—it is perhaps enough to cite Cardinal Hlond’s notorious pastoral letter of 1936. To his credit Father Kolbe distanced himself, as Schlafly and Green point out, from an ultra-extremist like Trzesiak, but it is also worth recalling that there were a number of distinguished Poles—although he was not among them—who took a firm public stand against anti-Semitism at this time. (Some of their names are listed in Celia Heller’s book.)

Messrs. Schlafly and Green are, I think, unfair when they run together my comments on Father Kolbe with those of the newspaper which described him as a “rabid racist.” In fact I tried to make it clear that he always regarded conversion to Christianity as the highest aim, a view which is needless to say incompatible with racism, at any rate racism of the full-blown pseudo-scientific variety. On the other hand I feel in retrospect that I ought to have said something about the Jews who were sheltered in Niepokalanow in 1939-1940. I was irritated by Patricia Treece singling out this episode, while omitting so much else about Kolbe’s attitude to the Jews (and glossing over the question of Polish-Jewish relations generally); but I should have mentioned it nonetheless.

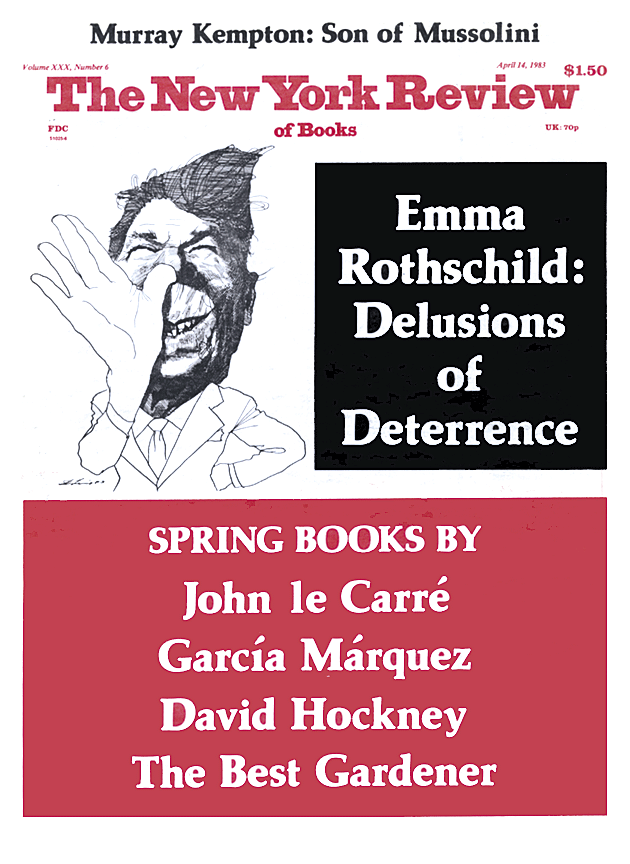

This Issue

April 14, 1983