—Washington

The latest chapter of Watergate, the chapter being written by Ford, involves two interrelated matters. One is the pardon for Nixon and perhaps later for his aides. The other involves the disposition of the Nixon tapes and related materials. The full dimensions of this continuing cover-up have yet to be fully appreciated.

The net effect intended may easily be summed up. It is to let the culprits go free and send the full truth to the gas chambers. For the Ford-Nixon agreement on the tapes allows Nixon to control access to them during his lifetime and to destroy any of them he chooses after five years. After ten years, or upon his death should that come sooner, all the remaining tapes are to be destroyed. Destruction of these tapes is the essential first step to any Nixon comeback as a political influence.

Whatever secrets on those tapes Nixon has fought so hard and successfully to hide all these months will remain forever unknown. Nixon will be able to write his own story of his administration without being embarrassed by them, except for those disclosed in the tapes already obtained by Jaworski. The way is thus opened to poisonous untruths about his forced resignation which may some day prove injurious to the political health of our country.

There are two immediate steps Congress could take to preserve these tapes from destruction and to prevent the agreement from taking effect. One is for the judiciary committees of either or both houses to subpoena the tapes as part of an investigation into their disposal.

The second is to summon the attorney general and ask him to explain in plain language the tortured meaning of his convoluted legal memorandum which was released with the announcement of the tricky deal between the Ford White House and Nixon on the tapes.

The legal opinion was released as if it supported the tapes agreement. But a closer reading leads to other conclusions. The legal memorandum does say, in a curiously negative way, that these tapes can be considered Nixon’s property. But it concludes by advising the White House that none of the tapes or other materials “can be moved or otherwise disposed of” without court permission where subpoenas or other judicial orders are outstanding. This is so, the legal opinion says, because in both civil and criminal cases subpoenas may be issued “directing a person to produce documents or other objects which are within his possession but belong to another person.” The tapes and other materials covered by the agreement were left behind in the White House or deposited previously with the General Services Administration.

The agreement provides that all this material be removed from the District of Columbia, where the cover-up cases are being prosecuted, and “deposited temporarily,” so the letter of agreement by Nixon provides, “in an existing facility belonging to the United States, located within the State of California near my present residence.” The facility referred to is the so-called Laguna Miguel pyramid near San Clemente.

When Ford’s lawyer Philip Buchen was asked at his September 8 briefing when the tapes and other materials would be moved to California, he said, “As soon as we can get rid of, or modification of, the existing orders that require they be retained here.”

He admitted there were at least three sets of judicial orders requiring that some at least of the tapes be kept available here. But none of these cases covers or protects all the tapes whose subpoena by the House Judiciary Committee was disregarded by Nixon or all the tapes and other materials which may prove necessary in current or future investigations by Special Prosecutor Jaworski. It is important that the judiciary committees and Jaworski be forced by public opinion to go into court and assert their rights to block the transfer agreement and save the tapes for posterity.

The first judicial order requiring the White House to maintain custody of tapes despite the Ford-Nixon agreement was issued by federal judge John H. Pratt on September 11 in connection with Watergate-related suits brought by R. Spencer Oliver, head of the Association of State Democratic Chairmen, and by James W. McCord, Jr.1 Judge Pratt’s order covers four months of Watergate tape recordings.

In these cases the Ford administration has already begun to try to use its agreement with Nixon as a means of escaping judicial involvement in Watergate cases. Buchen, ordered to give a deposition in these cases September 12, filed an affidavit saying that while the tapes were still in the White House, they were now the property of Nixon under the new agreement and any subpoenas should be taken up with the ex-president.

We can now begin to see that Ford and Nixon have a common interest in extending the pardons as soon as possible to other Watergate defendants who have yet to be tried. For Ford it may prove hard to avoid the ticklish problem of tape subpoenas as long as prosecutions are under way. Nixon for his part would not want to have to appear as a witness in the trials. In addition, as long as they are in prospect he must contend with subpoenas and possible contempt citations even if he can get the tapes into his possession. There is for him always the danger that some tapes may have to be produced with more damage to his reputation. No doubt he will plead executive privilege to resist subpoenas as Truman once did when called to testify after leaving office. Only general pardons can protect both Ford and Nixon from all these unpleasant possibilities.

Advertisement

The Ford administration is trying, by a private agreement with Nixon, to evade its responsibility to produce tapes still in its physical possession. That is what the attorney general’s opinion says the Ford administration cannot do. But that is exactly the obligation the agreement with Nixon tries to evade. For the terms laid down by Nixon and countersigned for the Ford administration by Arthur F. Sampson, head of the General Services Administration (as if it were some routine custodial matter), are that in the event of any subpoena or other judicial order for tapes or papers Nixon alone is to decide whether to obey or contest the order.

Nixon will respond “as the owner and custodian of the Materials [as the tapes and other documents are termed in the letter of agreement], with sole right and power of access thereto and, if appropriate, assert any privilege or defense I may have.”

Should Nixon agree to produce the requested material, the government could then and only then, step in—but only to raise additional objections! Nixon wrote, “Prior to any such production, I shall inform the United States so it may inspect the subpoenaed materials and determine whether to object to its production on grounds of national security or any other privilege.”

This is very different from the situation which existed before this questionably legal agreement was secretly signed on September 6, two days before the Nixon pardon was announced. In the event of a subpoena for documents Nixon left behind in the White House or with the GSA, it was the Ford administration that had to decide whether to obey the subpoena and if not on what basis to disobey the order for the tapes or other materials.

In other words, Ford had to decide whether to act just like Nixon or to take a fresh look at the public policy involved and adopt a more open, a more forthright—and to echo a word the new president himself picked for the hallmark of his administration—a more candid policy.

The choice was especially embarrassing because of the pledges made by Ford not to invoke executive privilege against court orders when questioned by Senator Byrd at the Senate Rules Committee hearing on his nomination as vice president, the same hearing in which Ford said, “The public wouldn’t stand for it” if he pardoned Nixon.

Byrd confronted Ford with a speech Ford made in 1963 in the House of Representatives condemning the invocation of “executive privilege” in Teapot Dome, Truman’s tax scandals, and the Bay of Pigs affairs. He said the doctrine was usually a cover for “dishonesty, stupidity and failure of all kinds.” Byrd said, “The shoe is on the other foot now,” but Ford replied he still felt the same way. Byrd led him through a stiff interrogation2 which now has a fresh and immediate relevancy.

Byrd: Is it your opinion that withholding of information which may go to the commission of serious crimes is justified under any circumstances when ordered by a president?

Ford: At this time I have not foreseen it, but that is a pretty broad statement. At the moment, I cannot foresee any.

* * *

Byrd: Would you, Mr. Ford, at the high mantle of presidential authority, if it were ever bestowed upon you, invoke presidential privilege to prevent the courts rom seeing documents the courts ordered you to hand over to the courts?

Ford: …if I had to weigh those two, the political public impact on the one hand, and the legal and constitutional issues on the other, I think my judgment would be to make them available….

This answer seems to reflect an instinctive opportunism: constitutional considerations should prevail over political impact. But now that the time has come to fulfill this implied promise, Ford’s answer is to enter into a surprise agreement by which the government hands over the tapes and other documents to Nixon’s sole authority, transporting them to California and housing them near him at public expense. Nixon in return makes the government a “gift” of the documents, but this is to take effect only five years hence and is subject to the provision that Nixon can destroy all the tapes he wishes after five years and the rest must be destroyed after ten years or on his death. Thus Ford evades his moral and political responsibility and carries on the cover-up.

Advertisement

This is of a piece with his conduct on the pardon. He gave the Senate committee and the country the clear impression, without saying so directly, in that disingenuous style of the Nixon and Lyndon Johnson eras, that he would not issue a pardon to Nixon. “I do not think the public would stand for it” has proven to be his most accurate prediction.

Ford made another implied pledge at the same hearing which also deserves more notice than it has received. “The attorney general,” he said, “in my opinion, with the help and support of the American people, would be the controlling factor.” This implies that the attorney general would be consulted in advance of a decision on pardon—otherwise how could his views possibly be “controlling” and how could public opinion help him block a pardon? But the attorney general said the day the Nixon pardon was announced and has repeated several times since that he was never consulted on the Nixon pardon.

If this is true, and Saxbe’s press aides keep repeating it, then the attorney general was as much taken by surprise as Congress and the country. The surprise was all the stronger because at Ford’s press conference of August 28 he over and over again gave the impression that he would take no action on a Nixon pardon until legal process had run its course. Yet we now learn that only two days later he disclosed to a few intimates that he had decided to pardon his predecessor. Duplicity is the only word for that sequence.

The same secretiveness appears in the case of the tapes agreement. Despite the historic importance and legal complexity, there was no consultation with the attorney general in advance—so Saxbe’s press officers insist. They say he did not hear of it until it was announced, that the legal opinion he furnished—which the White House released with the agreement—was written before he knew about it. These are all matters which should be explored with the attorney general in a public congressional hearing preparatory to a legal challenge of the deal itself.

There is some reason to suspect that the attorney general, like the rest of the Ford entourage, is being a little tricky. His legal opinion, fourteen opaque pages, is a masterly job of scholarly obfuscation, skillfully designed both to give the White House just what it needed and yet to protect the attorney general’s flank from criticism.

The draftsman was the head of his office of legal counsel—the intricate footwork is beyond the capacity of Saxbe himself—but for all the research the memo could only cite two cases for the proposition that the tapes and all other presidential documents are the private property of Nixon.

Even to find two cases the memo had to scrape the bottom of the legal-historical barrel. Only one case has to do with presidential papers. In the other, the memo culls some dubious dicta about oil leases on public lands (US v. Midwest Oil Co. 236 US 459 in 1915) which say that rights may be established by congressional acquiescence.

The case bearing on presidential papers, a decision on Circuit by the famous constitutional commentator Mr. Justice Story (Folsom v. Marsh 9 F. Cas. 342 in 1841), dealt with a copyright problem in publishing the works of Washington. As a precedent this is skewed because here we are confronted with the opposite problem—Nixon’s burning desire to keep his tapes out of the Works of Richard Nixon and forever unpublished.

Anyway this decision by Mr. Justice Story could be used to uphold a proposition directly contrary to that sought and applied by Ford and Nixon. Mr. Justice Story said at one point that the courts had to distinguish, in dealing with presidential papers, between the private and the official papers. The latter were affected with a public interest and the government had a right to decide on the one hand whether they could be published at all and on the other—

…from the nature of the public service, or the character of the documents, embracing historical, military or diplomatic information, it may be the right, and even the duty, of the government, to give them publicity, even against the will of the writer.

The added italics nicely fit the case of the Watergate tapes. But Saxbe’s memorandum interprets this very narrowly as applying only to the censoring of national security information, an interpretation which perfectly fits Nixon’s penchant for seeing national security information almost anywhere.

The Saxbe memorandum also selects one sentence from the report on Nixon’s tax returns made last April 3 by the staff of the Congressional Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation. This 780-page report limited its discussion of the question “Who Owns Presidential Papers?” to two half pages (28-29), perhaps because quite a few congressmen have also been in on the racket of “bequeathing” their papers for tax advantages.

Saxbe’s memo quotes from this one page the assertion that “the historical precedents taken together with the provision set forth in the Presidential Libraries Act suggest [our italics, not a very strong word] that the papers of President Nixon are considered [again our italics] his personal property rather than public property.”

The report on Nixon’s taxes says that in passing the Presidential Libraries Act Congress “suggested” that it agreed with this view by authorizing the GSA to accept for deposit “the personal papers and other personal [again our italics] historical documentary materials of the present President of the United States [Truman].”

But are the Watergate tapes Nixon’s “personal” property? Has he the right to destroy records of the criminal conspiracy, which sent so many of his associates to jail and drove him from the presidency? The Saxbe memo did not quote the report’s prescient observation that allowing absolute ownership may tempt some public officials “to destroy certain sensitive papers” or its softly spoken but cogent suggestion that “in view of these diverse considerations, it may be that the whole question of the ownership of papers of public officials is a matter which the appropriate congressional committees might want to consider.” There couldn’t be a better time than now.

Article IV, Section 3, Paragraph 2 gives Congress alone the power to dispose of government property. The Congress has never used this power to regulate the disposal of public papers. “A President’s papers,” the Joint Committee report said, “may contain much that is essential in conducting the national business in subsequent administrations.” This certainly holds true of the investigations and trials still underway in connection with Watergate.

The report on Nixon’s tapes also touched on the danger that presidents “may make future historical work more difficult” by how they handle their papers. The Ford-Nixon agreement would certainly do so by arranging for the destruction of the tapes and allowing Nixon in the meantime to control all access to them.

The Ford administration is fully aware of all this, and quite cynical about it. The cynicism was all too evident in the press briefing September 8 by Ford’s friend and lawyer, Buchen. When asked why the tapes “were going to be destroyed after five years,” Buchen first adopted a civil liberties posture to defend this, calling himself “an old spokesman for the right of privacy.” Thereupon this gem of an exchange—

Q: Mr. Buchen, was any consideration given to the right of history?

Mr. Buchen: I am sure the historians will protest, but I think historians cannot complain if evidence for history is not perpetuated which shouldn’t have been created in the first place.

This was Nixonism, pure and undefiled.

An honorable man in Ford’s shoes before entering into his tapes agreement with Nixon would have consulted the attorney general, the special prosecutor, and the judges who have cases involving Watergate or the tapes. He would have sought the advice of Chairman Ervin of the Senate Watergate investigation committee3 and Chairman Rodino of the House Judiciary Committee, both of which still have outstanding subpoenas for tapes which Nixon refused to honor.

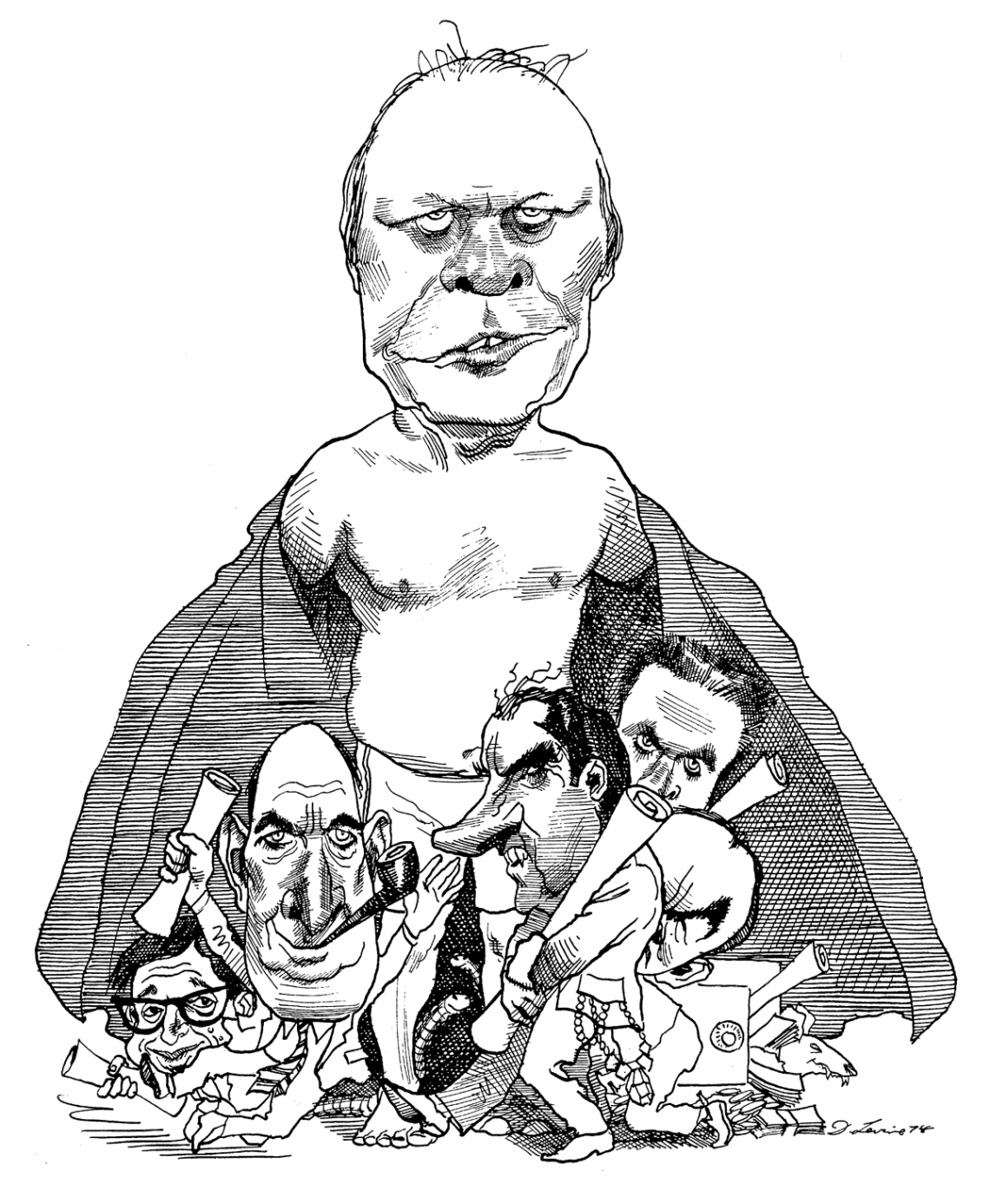

At his confirmation hearing Ford over and over again expressed disagreement with the withholding of these tapes by Nixon. That he has now acted so differently, and so covertly and so swiftly, speaks for itself about the true character of Gerald Ford. Tricky Dicky has been replaced by Foxy Ford. All this will deepen the suspicion that the pardon was part of a prenomination deal. If not, Ford could have plainly said so before the Senate committee last November instead of evading the issue with his disingenuous remark that “the public wouldn’t stand for it.” Was he then telling the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth—so help him the God he evokes as effusively and frequently as did Nixon before him?

—September 12

This Issue

October 3, 1974

-

1

These suits and a similar action by E. Howard Hunt involving the tapes are in addition to the three cases cited by Buchen at his September 8 briefing. These are the Wounded Knee trial in Minnesota, the suit brought by the TV networks which gave money to the Nixon 1972 campaign on the implied assurance that this would protect them from anti-trust prosecution, and thirdly, a civil suit brought by persons barred from a Billy Graham Day celebration in North Carolina. It is significant that Buchen “forgot” to mention the three pending Watergate cases though he himself is under court order in them. ↩

-

2

See pages 39-42 of Senate Rules Committee hearings on the Ford nomination. ↩

-

3

Senator Mondale has already written Senator Ervin in the latter’s capacity as chairman of the Senate Government Operations Committee asking him to subpoena “all relevant presidential materials [on Watergate] in order to establish the right of access to such materials and to guarantee their preservation.” He also suggested an Ervin committee investigation as the best way “to accomplish full disclosure and to probe the propriety of the GSA agreement” between Ford and Nixon. ↩