This extraordinary work is clearly the most literate, intellectually agile, and sharply focussed analysis of the function of American education in its historical and cultural context to be found in the professional literature of education. This statement does it less than justice; I by no means wish to imply that the book stands out only in comparison with the low, prevailing standard of the area. In any field it would be outstanding; in my own it is, by its quality—though not its import—reassuring as well. It is the sophisticated work of exceptionally cultivated men; indeed, its sophistication is its chief challenge to a reviewer. What immortal hand or eye could frame its fearful sophistry? Still, I shall try, and so will a good many others, for this book raises moral issues that are much more important than its educational implications. It is destined to be both eulogized and damned. This is not a prediction. It is a promise I intend to carry out here and now.

There will certainly be little disagreement with the authors’ selection or definition of the central problem they discuss:

Unless we can find an educational solution to the problem of commitment, then the wonderfully dynamic, ordered, and free society of America will neither achieve nor merit long continuation. Perhaps we may be allowed a few personal words to explain our attitude….As we sought a panoramic vision of American life, what caught our attention most strongly at first was evidence of the enormous physical costs that our civilization demands of its citizens. Our strategic vantage point in the educational system of America, as well as considerable time spent abroad over the years, enabled us to see with shocking clarity what America was doing to people. The experience left us for a time curiously cynical and hostile. There were times when the direct question, “What distinctly American traits in contemporary culture are worth preserving?” would have drawn a direct “None!” for and answer.

But we are suited neither by training nor temperament to be consistent nihilists. As we gradually learned to see and to describe the system of American life with at least partial success, we also came to know and value the goods which cost Americans so dear in the currency of the soul….We did, in our own way, learn assent to this new society, a society that offers no fixed and eternal ends in life, but only powerful dynamic means, as its major gifts to the individuals that make it up…Learning assent to the new society does not mean easy and passive acceptance of the status quo, a facile adjustment to life as it is encountered in the immediate vicinity. It does mean taking one’s full part in the impersonal, complex (and therefore overwhelming) public, corporate world, as well as in the intensely personal, private (and therefore overwhelming) world of the mobile small family. In short, it means knowing the costs of modern life and being willing to pay them on demand. Believing that the world is worth the cost, we direct this book toward a conception of education through which our youth may learn assent to America.

A major reason that we make ourselves miserable in America, the authors believe, is that we cannot make the values appropriate to a more individualized society operate effectively in the corporate and bureaucratic world we live in, and they maintain that these values must be revised and made relevant to the conditions of modern life in America. In a brilliant and original chapter on Dewey and progressive education, they demonstrate that, despite his experimentalism—they call it pragmatism—Dewey could not quite perceive how well-suited modern life and his philosophy of continuous reconstruction of experience really were to each other:

There is a lesson to be learned form Dewey’s mistake here. In the final analysis his conservatism overcame his devotion to change, growth and process. Deeply convinced that ultimate human values were to be found in a particular form of face-to-face community, Dewey was so concerned to see that community survive and grow that he forgot to notice one particular fact: the world no longer has a place for it. The full acceptance of change does not admit of the reservations which Dewey never overcame….But we have to acknowledge and accept that structure. We cannot regard Tom Sawyer as an acceptable model for intelligence in the modern world. Neither can we take the Vermont village of Dewey’s childhood as representative of the needed social commitment of our time.

In their context, these comments are not snide; they are the concluding sentences of a discussion in which both Tom Sawyer and Vermont are treated with understanding and respect, though they are finally rejected. This rejection of personal experience and loyalty as obsolete responses is the recurrent and insistent motif of the book. A deft, though familiar, historical analysis of the development of American culture from the agrarian to the metropolitan; a thoughtful discussion of the American conviction that science is the only possible metaphysics; an original and highly provocative synthesis and presentation of the evidence that the modern corporation destroys the moral and political as well as the economic basis of the small, local community without replacing it, provides a firm foundation for the authors’ argument.

Advertisement

But their social analysis, of course, is not and cannot be very different in its implications from those of Riesman, Whyte, Galbraith, Mills, and Berle, whom they briefly but cogently cite. What makes Kimball and McClellan different is their insistence that we are stubbornly resisting these implications and thereby refusing to assent to America. Life in America today demands that we learn to live so as to make virtues of transiency and flexibility; we are not to seek for roots; for us, the authors assert, to stand still is to die: “A blind necessity to keep moving is the most obvious fact about all contemporary valuing behavior.” Only in the family can we look for stable ties; yet the ability of the family to supply them is weakened by its own rootlessness in the succession of communities in which it must try to establish itself, and even more by its anxious involvement in grooming its children for mobility. All this must be accepted. How, then, is commitment to be achieved?

To answer this, Kimball and McClellen argue that in any society with well-defined social roles people learn to do, and desire to do, what their role requires. What they believe to be their personal commitment, then, is not nearly so much a matter of feeling as of social function. If the young can be instructed in the arts of manoeuvre in the modern world, they will, in effect, become committed to the socially essential postures of manoeuvre; and the fact that this precludes strong personal feeling about what they do or strong personal ties to the people they do it with merely means that this is a new kind of commitment—commitment to particular individuals or groups outside the family, or to specific social goals, having become invalid and nostalgic. Toward the end of their book, the authors bring this argument to a focus:

The final part of our task is to defend our analysis against the obvious charge that commitment is something other than the purely intellectual or cognitive activities that we have described under the heading “disciplines.” Commitment is a matter of guts, of will and heart, the objection runs; commitment means a certain state of the emotions and not merely of the mind, as our argument would lead one to believe.

Let us meet this objection head on. It is an idea that is deep-rooted in our culture, and we shall have to make several detours to show why it is entirely misplaced…We shall have to offer an interpretation of individuality and individual responsibility that is different from the one our culture inherited from its agrarian past. With these arguments we shall make our case proof against the objections that seem, at first glance, so destructive.

They fail to do so, however, and reiterate their point in the statement:

In short, part of the price of being an American is being an organization man. Autonomy is not, as Whyte would have us believe, a viable alternative. On the contrary, the very attempt to discover an alternative is a form of mental and social illness, a denial of reality. The important question is not whether, but what kind of an organization man? One who simply occupies a niche on an organizational chart? Or one who strives to extend the bounds of his own freedom to act with initiative and resourcefulness at whatever level he finds himself? Truly to understand the reality of the dynamic world we live in is to see that the second sort of individual is not only preferable ethically but that without him our emerging social structure will not stand.

“The rat-race-and-withdrawal theory of public life is so much a part of the climate of opinion among contemporary intellectuals that its public expression,” Kimball and McClellan write, “cannot seem other than trite.” They underestimate the opposition; and calling it nostalgic and socially ill does not wholly disarm it. Matthew Arnold, over a century ago, understood the reality of the dynamic world we live in well enough to plead:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To live before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

“Dover Beach” is familiar, but not trite; and Arnold’s vision of the world is very similar to Kimball and McClellan’s. Only assent is lacking.

Advertisement

What is the nature of the assent that Kimball and McClellan demand? They do not ask that our society be enthusiastically endorsed; only accepted as what in fact exists, as Margaret Fuller ultimately accepted the universe. This is sound advice; but to accept reality implies no obligation to approach it pragmatically. A woman awakening in bed with a strange man ought to be mature about her problem. But it does not follow that she is obligated to go into the kitchen and start cooking breakfast. It might be wiser to kill him; in part, it depends on how she feels.

“We must force the question,” the authors write, “whether it is humanly possible to develop a viable sense of relatedness of self to a world within the contemporary urban-industrial culture.” Indeed, we must; but some answer it differently. Thus E. M. Forster wrote in “What I Believe:”

I have, however, to live in an Age of Faith—the sort of epoch I used to hear praised when I was a boy. It is extremely unpleasant really.….And I have to keep my end up in it. Where do I start?

With personal relationships. Here is something comparatively solid in a world full of violence and cruelty….Personal relations are despised today. They are retarded as bourgeois luxuries, as products of a time of fair weather which is now past, and we are urged to get rid of them and devote ourselves to some movement or cause instead. I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country…There lies at the back of every creed something terrible and hard for which the worshipper may one day be required to suffer, and there is even terror and hardness in this creed of personal relationships, urbane and mild though it sounds. Love and Loyalty to an individual can run counter to the claims of the State. When they do—down with the State, say I, which means that the State would down me.

That, of course, depends of the State; ours would, and often has. Forster published this essay, however, in 1939, at a time when Britain was not altogether unconcerned with survival.

Kimball and McClellan’s stigmatizing of the preponderance of contemporary intellectuals as morbid and narcissistic would seem to leave such people as E.M. Forster out of account, although their mixed and distinguished bag includes Freud, Fromm, Tennessee Williams, Norman Mailer, and that most pied of pipers, J.D. Salinger. By citing Arnold and Forster I do not, to be sure, refute Kimball and McClellan’s basic contention that all these men are dinosaurs. But I can, perhaps, refute their assumption that the dinosaurs are all impotent or dead. No book dealing formally with education is ever likely to influence secondary education so much as The Catcher in the Rye, which by now has helped millions of youngsters to diagnose their plight and learn an effective defensive stance, even though that stance has often been a pose. And the most dynamic of American moralists and social critics—the greatest of these is James Baldwin—can certainly not be accused of turning away from society, although I’ll bet society wishes they would.

Reviews of books are written for people who have not yet read them; and Kimball and McClellan’s potential readers may well feel that I have not given their specific educational recommendations the attention they deserve. I think I have; their concern with “the formal disciplines of logic and mathematics,” “experimentation,” “natural history,” and “esthetic form” add up to far less than an adequate program for bringing about the kind of changes they advocate in students, although they would certainly improve the intellectual tenor of the schools if they could be made to work there. Here, however, the authors are blithely unpragmatic, neglecting the context in which such changes must occur—the public schools—except to complain, justly enough, that they are overly bureaucratized; and therefore deny the student the opportunity he needs to practice the skills of group-functioning under conditions conducive to autonomy.

This is sensible and consistent: organization men, surely, should be protected from exposure to futile and incompetent organizations during their formative years. But the authors’ devotion to the ideal of functioning well in a highly organized society leads them to ignore most of the issues that educationists think important; and this is not simply because the educationists are more naive than they. Kimball and McClellan, though occasionally noting the plight of the poor in America, actually concern themselves wholly with middle-class education and the task of filling up the emptiness of suburban life-in-transition with their new type of commitment. Yet the crucial failure of American education to provide slum youngsters, or working-class youngsters who are not on the make, with anything the kids see as valuable constitutes a national emergency. The book does not discuss human development in childhood and adolescence. On its terms, it cannot; adolescence is a period of life that makes no sense at all to an observer unless he does understand and care about the youngster’s individual identity and commitment, and quest for self-fulfillment. But these authors state that:

This period poses special educational problems for two reasons: 1) It will see the termination of that period in which formal education is conducted apart from occupational interests and the beginning of the period in which formal education is closely integrated with occupational pursuits. 2) It will constitute the period in which the disciplines of thought and action of the adult society become conscious and foundational to all future learning.

Those two reasons, impressive as they sound, don’t quite cover the special educational problems of adolescence: and anybody—especially any pragmatist—who thinks they do could easily learn better almost any evening in the course of a ten-minute stroll through upper Central Park. Two pragmatists together might take a little longer.

No, this is primarily a moral treatise, not a book about education. The style of the authors is quite frequently hortatory; and sometimes offensively so. The first lines of the preface assert that:

The present volume is the offspring of an academically un-sanctioned union of anthropology and education. In popular mythology, natural children are supposed to be marked by excessive vigor and ruthlessness in the pursuit of goals. If these qualities are present in this book, we should count them assets.

So should I; but what comes out is not so much an effect of strength as a kind of seductive insolence. On two or three occasions, the authors step into parentheses to admonish the stupid reader directly: “(It is idle chatter to introduce the bogey of transfer of training to this discussion….”;”Please do not interpose the trite objection that the social contributions of Bartok, Bergson, and Bohr cannot be explained by their group affliations!…).” Ordinarily, I would not object to this kind of thing; it is even refreshing after so much blandness in books about education. But in this book, otherwise so elegant and satisfying in style, it began to affect me very unpleasantly. One need not be a Swinburne to get a certain satisfaction from being pushed around by rough, manly chaps, even intellectually; and Kimball and McClellan leave the susceptible reader all a-tingle. But they also left me feeling, as sometimes happens on these occasions, slightly taken. By treating me with such engaging roughness, they almost made me forget that the new brand of commitment they are selling, that works on an entirely new principle, was so delightfully smooth. I enjoy myself. I am grateful for our romp together, but I am not going to buy their product. Freud, Fromm, and Salinger are high-priced, it is true; more than I can any longer afford. But they carry my brand, and their goods last a lifetime, such as it is.

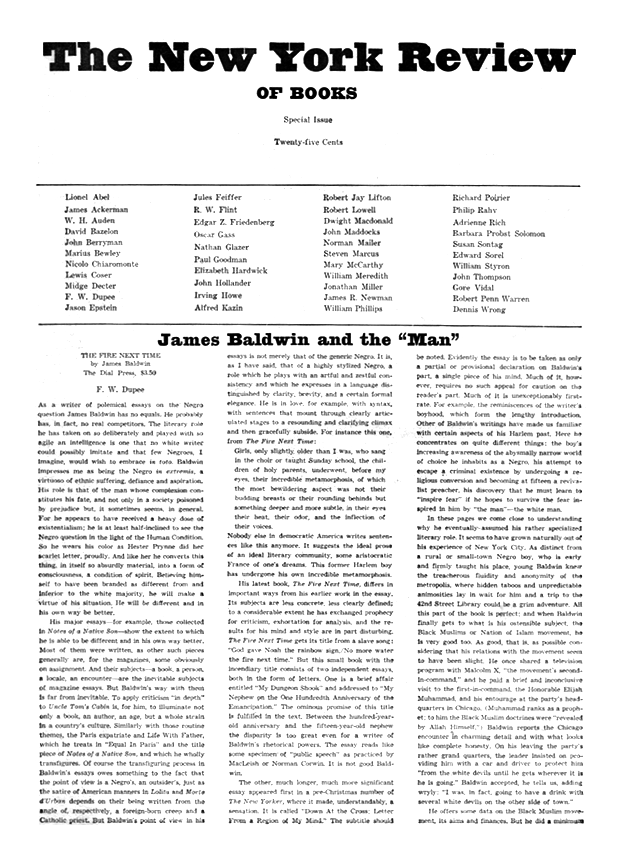

This Issue

February 1, 1963