This is a selection from Kenneth Koch’s shorter poems. The volume includes none of his plays nor any passages from Ko or his other more or less lengthy narratives. The omission is perhaps a pity. Koch’s plays have a special appeal: they give a peculiarly succinct and eloquent form to his enormously animated conception of things. Yet his better poems convey that conception too, in their own way.

Koch’s position in modern poetry is not easy to determine. It may help to begin by pairing him with a long-established elder poet to whom his relations are close enough in some respects, and distant enough in others, to be instructive. In part he is one of those “literalists of the imagination” who are commended by Marianne Moore and whose principles are exemplified in her own work. Like Miss Moore, Koch is fond of making poetry out of poetry-resistant stuff. Locks, lipsticks, business letterheads, walnuts, lunch and fudge attract him; so do examples of inept slang, silly sentiment, brutal behavior and stereotyped exotica and erotica. Whatever helps him to “exalt the imagination at the expense of its conventional appearances” (Richard Blackmur’s formula for Marianne Moore) is welcome, although not to the exclusion of the sun, the sea, trees, girls and other conventional properties. But Koch rarely submits either kind of phenomenon to any Moore-like process of minute and patient scrutiny. He is an activist, eagerly participating in the realm of locks and fudge at the same time that he is observing it. And if, like Marianne Moore, he is always springing surprises, he does not spring them as if he were handling you a cup of tea. Her finely conscious demureness is not for him. For him, the element of surprise, and the excitement created by it, are primary and absolute. In short, life does not present itself to Kenneth Koch as picture or symbol or collector’s item. It talks, sighs, grunts and sings; it is a drama, largely comic, in which there are parts for everyone and everything, and all the parts are speaking parts.

Filmed in the morning I am

A pond. Dreamed of at night I am a silver

Pond. Who’s wading through Me! Ugh!

Those pigs! But they have their say elsewhere in the poem, called “Farm’s Thoughts.”

The thirty-one poems in this volume were written during the past ten or twelve years and are very uneven in quality. Some of this unevenness may be the result of a defective sense of proportion, even a defective ear, on the poet’s part. Mostly, it seems to spring from a certain abandon inherent in his whole enterprise. Koch is determined to put the reality back into Joyce’s “reality of experience,” to restore the newness to Pound’s “Make it New,” while holding ideas of poetry and of poetic composition which are essentially different from those of the classic modern writers. In his attempt to supersede—or transform—those writers, Koch seems to have drawn upon a good many far-flung sources; they range from Kafka to certain recent French poets, including Surrealists, to Whitman, Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams and others in the native book.

His general aims are made clear—well, pretty clear—in a dialogue poem called “On the Great Atlantic Rainway” which starts the present volume off. A.T.S. Eliot character is uncomfortably present at the exchange of views: “an old man in shorts, blind, who has lost his way in the filling station.” A wise old Yeatsian bird, also on hand, finds occasion to remark: “And that is our modern idea of fittingness.” But our poet raises these ghosts only to shoo them away. His own idea of fittingness is to shed all formulas, “to go from the sun/Into love’s sweet disrepair,” to await whatever forms of “unsyntactical beauty might leap up” beneath the world’s rainways. In other words, he will flee the sunlight of approved poetic practice, staking his poetic chances on whatever wonders may turn up in the wet weather (“rainways”) of unapproved poetic practice. He will talk to himself, improvise, consult his dreams, cherish the trouvaille, and misprize the well-wrought poem.

Such, as I make it out, is Kenneth Koch’s unprogrammatic program (or a part of it), and the calamitous possibilities in it are obvious. Like the similar program of certain of the Beats, it could turn the writing of poetry into a form of hygiene. It could and does: some of Koch’s efforts, like many of theirs, suggest the breathing exercises of a particularly deep-breasted individual. “Fresh Air,” his most overt attack on the poetic Establishment, is half a witty skirmish, half an interminable harangue. The Unconscious dotes on cliches; and those unsyntactical beauties supposedly lurking beneath Koch’s rainway sometimes turn out to be discarded umbrellas. Consulting the sybil of the unconscious, moreover, he is sometimes stuck with mere mouthfuls of images and with lines of verse that make no known kind of music. “I want spring. I want to turn like a mobile/In a new fresh air.” He might start by freshening up his images. “I love you as a sheriff searches for a walnut / That will solve a murder case unsolved for years….” Back to the Varsity Show with him. And if his verse is sometimes lacking in the delights of a reliable style, it also offers few of the conveniences of a consistent lucidity. To me his idiom is often a Linear B which remains to be cracked.

Advertisement

But having deciphered quite a lot of it, I feel hopeful that the rest will come clear in time. And for the sheriff and the mobile there are constant compensations. There is “a wind that blows from / The big blue sea, so shiny so deep and so unlike us.” Marvelous. And there is the strange excitement aroused by this beginning of a poem called “Summery Weather.”

One earring’s smile

Near the drawer

And at night we gambling

At that night the yacht on Venice

Glorious too, oh my heavens

See how her blouse was starched up

“Summery Weather” is a poem of only twenty-five lines, into

which is concentrated much of the romance of travel as well as much of the banality of that romance.

There are also several poems of greater length in the volume, two of the best of them being “The Artist” and “The Railway Stationery.” Both can be read as portraits of the artist, possibly as fanelful self-portraits of Koch himself in two of his many guises. The first is about a sort of mad Action Painter or Constructivist Sculptor who uses the American landscape as his canvas or showroom. A man with inexhaustible creative powers and many commissions, he consults only his sybil, coming up with a series of colossi which are neither artifacts nor art objects; and all the time he records in his journals various Gide-like reflections on the ecstasies and pangs of the creative life. “May 16th. With what an intense joy I watched the installation of the Magician of Cincinnali today, in the Ohio River, where it belongs, and which is so much a part of my original scheme.”

The Magician of Cincinnati happens to render navigation on the Ohio impossible. But never mind. The Artist will soon attempt something quite different. He never repeats himself—thank God.

“The Railway Stationery” is about a sheet of company letterhead; engraved on it is a half-inch engine which, when the paper is looked at from the reverse side, seems to be backing up; and there is a railway clerk who writes on the stationery, very carefully, a letter beginning “Dear Mary.” This poem, composed in blank verse as transparent as the stationery, as touchingly flat as the salutation, may be Kenneth Koch’s offering to the artist (lower case) in everyone and everything.

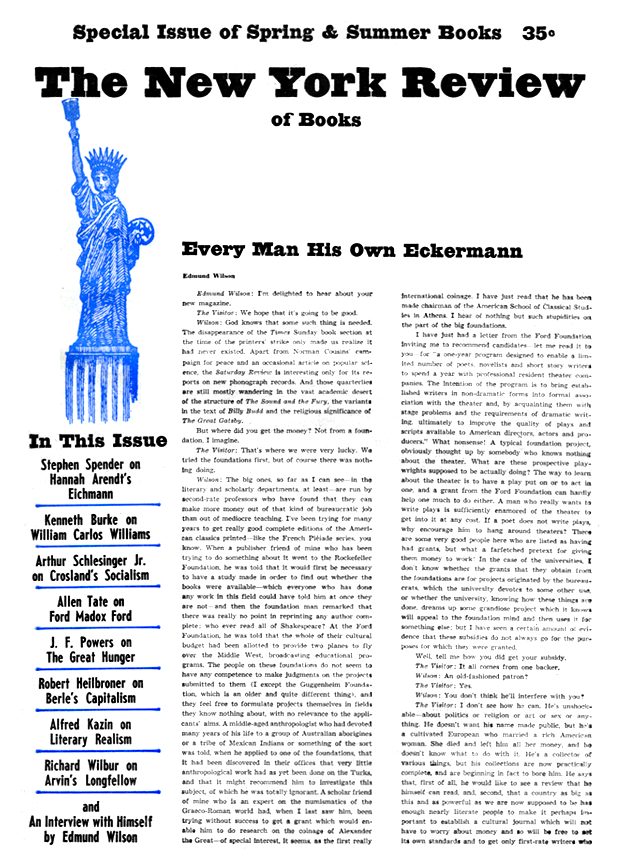

This Issue

June 1, 1963