Sooner or later, in our excessively redactive age, it was bound to happen. Unfortunately it is this long book which, like a shadow in a hall of mirrors, marks the final disappearance of a great subject. The subject itself is the “image of man” to be found (to readapt a convenient phrase) in “the crisis literature” of the modern age from Dostoevsky and Melville to Kafka and Camus and in the crisis theology and philosophy from Kierkegaard and Nietzsche to Martin Buber. Out of these, particularly as they appear in the fictional works of the first four, Professor Friedman (who, among other things, has done extensive translations of Buber’s works, as well as a book on Buber’s thought) hopes to fashion a master “depth-image,” as he calls it, in which modern man may find, at last, his full reflection. In a mixed mode all his own which runs together the extreme individualism of existentialist “anthropology” with the holism of much traditional ethics and the artistic ideal of imagist criticism and aesthetics, Mr. Friedman wishes to make “a decisive break with the universal ‘human nature’ of earlier philosophy and attain a picture of man in his uniqueness and his wholeness…” In order to do this, so he alleges, “one must move from concepts about [sic] man, no matter how profound, to the image of man.” How the philosopher-critic is to do this he does not explain; in fact what he says on this score suggests that it is impossible. “Our primary source of understanding man,” so he says, “is not (for example) Berdyaev’s systematic presentation of Dostoevsky’s thought on man, but Dostoevsky’s novels themselves with their completely unsystematic, paradoxical, contrary, but infinitely rich presentation of individual men.”

But of course the Dostoevskys have done their work. What is there left or even possible for Mr. Friedman to do? It is a bit hard to put into words. One way is to say that he does not, like the philosopher, offer a clear conception of man, nor, like the creative artist, true images of men and women, but rather, as it were a composite image that turns out to be, after all, only a fuzzy concept.

Something may be learned from all this: Never before, really, had I supposed that the abstract general images (he called them “ideas”) against which George Berkeley railed so harshly were more than the straw creatures of his own over-heated philosophical imagination. Now I know better: he was preparing us for Mr. Friedman.

But let us turn from Mr. Friedman’s aspirations to the realized substance of his book. The “depth image” of modern man which Mr. Friedman tries to define is a cross between Prometheus and Job. To this end he presents in Part I thumbnail sketches of the images of man as Exile and as Rebel that we have inherited from Greek and biblical sources along with sketches of the transitional medieval-renaissance figures of the Faust legend. Common to both classical prototypes is a view of man as an exile-rebel from and against but still, paradoxically, within a world-order.

But let us turn from Mr. Friedman’s them which is essential to Mr. Friedman’s purpose in the sequel. This difference, so he contends, is owing to the fact that the Greeks envisaged man and the gods as existing together within an uncreated, self-sufficient, pre-existing cosmos; whereas the Hebrews regarded the whole world as something created by a God who transcends His creation while remaining in a constant, vital dialogue with it. The biblical God is no first cause or prime mover, but a Divine Person with whom His creature never stops talking and quarreling, the point being, I take it, that talk itself, no matter how quarrelsome or abusive, is always redemptive. I am not so sure. Anyway, this “tension” (favorite word), which begins in Genesis with Adam’s disobedience and subsequent exile, becomes in Job something more, for Job himself is an exile who is also in active rebellion against God. As we find him in the Bible, however Job continues to reaffirm that his Redeemer lives, even while cursing Him and the day of his own birth. For Job in short, God so plainly and manifestly Exists, and his own tortured rebelliousness is itself a proof of the Fact.

With the coming of the modern age, man’s image of his context, and hence of himself and his relations to it, are profoundly altered. This may be seen even in “modern man’s” characteristic misconceptions of Prometheus and Job themselves. The former is now regarded as “the symbol of rebellion against all order, divine or social,” and the latter as the symbol of “an absolute exile that no dialogue with God may overcome, or of a metaphysical rebellion that aims to ‘do away’ with God….” And, in effect in the era of “the death of God” when men no longer believe in a cosmic order or in a creating, self-revealing God, both Prometheus and Job “live on divorced from their original context and transformed into the modern Rebel and the Modern Exile.”

Advertisement

The tale of this divorcement and transformation, as evidenced mainly in the writings of his novelists, occupies the later parts of Mr. Friedman’s book. It should be emphasized, however, that Mr. Friedman’s practice is not to move successively from author to author, offering us, in turn, rounded studies of the characters to be found in their stories; on the contrary, he scatters his occasionally acute discussions of most of the characters throughout the book where they keep reappearing as merely illustrative variations on such themes as “The Modern Exile,” “The Modern Promethean,” “The Problematic [sic] of Modern Man,” and “The Modern Job.” The effect therefore, is just the opposite of that which Mr. Friedman has led us to think of as desirable. For in his hands those intensely individual, if also symbolic, creatures, Ahab, Raskolnikov, K., and the rest become so many series of existentialist emblems. Now indeed one must reverse the existential order and exchange the recurrent word-type for the person-existence, a literary possibility no doubt, but not the one which Mr. Friedman himself intends.

Mr. Friedman’s moral, I take it, is that within the “general image” of modern man there remains the redemptive “specific image” of a “Modern Job.” (Shades of Berkeley: as we could have foretold, the distinction between concept and image comes to nothing.) This image, most fully actualized in Kafka’s K. and Camus’s Rieux, is still of a struggling, contending, rebellious being who remains, nevertheless, in a dialogical relationship to—what? That is the question. For Job there was a God; but for K. and Rieux who are “problematic rebels,” this evidently is no longer possible. They maintain only a “dialogue with the absurd.” What does this mean? To the Modern Job, contends Friedman, it does not matter whether his rebellion is expressed in the atheistic terms of a Camus or the theistic terms of a Buber. In both cases, “the basic attitude is essentially the same.” I should have thought that this is precisely not true. Mr. Buber’s God remains a Person, and it is precisely for this reason that he can conceive of his own relation to “ultimate reality” in dialogical terms. Camus plainly cannot. His attitude, despite Friedman, remains closer to Prometheus’s than to Job’s; more accurately perhaps, it is neostoic, like that of some other contemporary would-be yea-sayers who also have passed out of the orbit of Judeo-Christian experience.

The final chapter, “The Problematic Rebel and the Modern Job,” contributes nothing more to Friedman’s account of the human condition in our time. On the contrary, the contention that “The image of modern man that has emerged is an indivisible totality” is merely reasserted; and in fact it is simply false. And the concluding pages of the book are disfigured by a crude onslaught against Prometheus who, as Friedman now characterizes him, was, even in his original form, simply a symbol of science and of the civilization which science and technology make possible. Prometheus’s sense of justice and compassion are quite forgotten, and the modern promethean becomes a neo-pragmatist who (madness lies here) “can no longer regard his equations as universal laws but only as pragmatic formulae which answer the particular question that he has put,” or a neo-positivist who, “shunning metaphysical certainties,” “now don[s] the blinders of a one-sided language analysis to shut out of the realm of ‘true knowledge’ the broad human plain of ethics, religion, literature, and social values.” These modern prometheans “who find their emotional security in the prevailing ‘logical empiricism’ of our time seek a greater and greater certainty about an ever more restricted area of human significance.” And so on and so on. Who the devil are these cardboard monsters? Their grandpappy, thinks Friedman, is Hume; they include, among others, such psychologists and therapists as B. F. Skinner, Freud, Jung, and Erich Fromm, and, not least, Jean-Paul Sartre. The leopard cannot change his spots; but who, pray, is the leopard?

There is an extensive bibliography of works by and about Melville, Dostoevsky, and Kafka, but none of works by or about Camus or other authors discussed. Nor, most curiously for a book of such length and such varied and widely separated references to authors, books, and characters, is there an index. Thus does eccentricity compounded upon negligence once more reinforce the impression produced by the text: polymathic learning side by side with pockets of sheerest ignorance, sensitivity veined with brass, and depth contaminated with bilge.

Advertisement

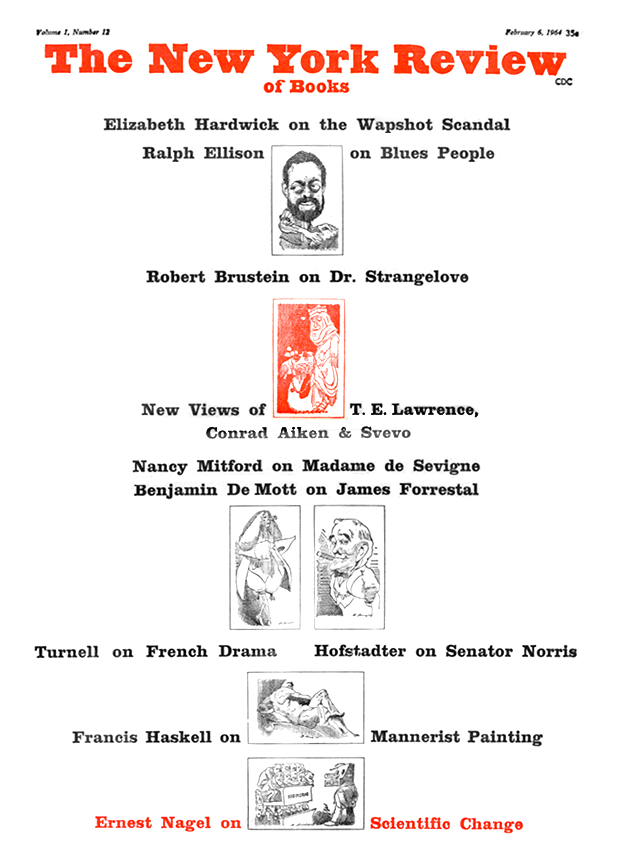

This Issue

February 6, 1964