There is something anomalous about a President’s keeping a diary. Only three out of the thirty-five have found the time to do it. They were John Quincy Adams, James K. Polk, and Rutherford B. Hayes (each of whom served only one term); the most literate of our Presidents, Jefferson, Madison, Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt (all of whom were re-elected), did not bother. By coincidence or not, the three men who did sit down regularly to confide their Presidential cares to a personal journal all happened to be, in a special sense, very inept political leaders. Adams disdained to build himself a party organization; Polk and Hayes managed to demoralize the organizations they inherited.

I am not so certain that the implied correlation is an altogether fanciful one. In matters of communication, a man of great public responsibilities does make choices on how he allocates his energies—and what sort of medium is a diary? The diary offers him a very subtle inducement to indulge in self-justification, and to divert his energies away from the real arts of persuasion, which are arduous and exhausting and involve a tremendous constituency of lawmakers, politicians, and public. The more time such a man spends with his diary, the less he seems to need to persuade anyone but himself that he is right and all who oppose him are wrong. Sensitivity is shifted, as it were, from the public to the private sector. A fascinating record of just such a process is, I think, set forth in the diary of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Few men have entered the White House with greater need for political skill than Hayes. Not only was he a minority President whose claim to office was tainted by charges of fraud, but he was a Republican saddled with a Democratic House of Representatives, a civil service reformer who owed his election to spoilsmen, and an avowed protector of the Negro committed to the early liquidation of Negro-supported carpetbag regimes in Louisiana and South Carolina. Yet despite the narrowness of his mandate and the serious limitations on his political maneuverability, Hayes had great plans for his administration. It was to be much more than a mere holding operation. Not only would he preside over the final pacification of the South, but he intended to take action that would accomplish a virtual revolution in American political life: he would return the country to a two-party system based on economic rather than sectional issues.

The first step would be the removal of Federal troops from Louisiana and South Carolina, ending any threat of further control by carpetbag oligarchies. Hayes would then appoint one, and possibly two Southerners to his cabinet. This was to be followed by a policy of selecting white conservatives for Federal office in the South without regard to party affiliation, and of seeing that Southern requests for Federal funds to construct badly needed canals, railroads, and levees were sympathetically entertained. All that would be required of the South in return was a pledge to respect the Negroes’ right to vote and to attend the public schools. Such a program, Hayes believed, would persuade the Southerners that he did not intend to interfere with their local affairs or to exclude them from Federal office. He was convinced that, this accomplished, the South’s seemingly monolithic commitment to the Democratic party would begin to crumble as economic issues again emerged as the dominant ones, and that sensible Southern conservatives would perceive that their true interests lay in the Republican rather than the Democratic party. This effort at regional diplomacy was to be accompanied by an equally serious effort to reform the civil service. Hayes hoped that such a step would both improve the quality of government officialdom and loosen the grip of spoilsminded professionals on the Republican organization, thereby enabling the “better element” to assume control.

To be sure, revamping political coalitions is a risky, delicate, and unpredictable business, but Hayes’s plan was not altogether utopian. Both North and South were sick of narrow political partisanship and sectional strife; psychologically the country was ripe for a period of moderation and stability. Moreover, Southern conservatives such as Governor Wade Hampton of South Carolina were quite willing to pledge full protection for the Negro in exchange for removal of Federal troops, and it did not go utterly beyond reality to imagine that if such men had the disposal of Federal appointments they might eventually come to head a new Republican coalition in the South. Hampton had already appealed for Negro support both in 1867 and 1876, arguing that the Negro and his former master were natural allies and promising not to tamper with the franchise or with the existing system of public education. And it was Southern votes, drawn by the very sensible logic that more Federal aid was likely to come from a Republican than from a Democratic administration, that finally broke the House filibuster which had threatened to block Hayes’s inauguration.

Advertisement

So the plan was not implausible. Still, there were plenty of hazards in it. For one thing, the Republican party had controlled the Federal patronage ever since the election of Lincoln, and political appointees had been a major source of both party energy and party funds. To try changing this system overnight would be both impossible and undesirable, and alternatives would certainly have to be found if Hayes intended to divorce the civil service from politics without wrecking the party. The situation in the South was even more touchy. The discredited leaders of the remaining Republican organizations would have to be eased out, but the trick was to do it while leaving the organizations themselves—and the loyalty of the Negro masses to them—intact. Conversely, every possible effort was needed to see that the South kept its pledge not to interfere with the Negro vote. For without that vote, there was little hope of building and maintaining a stable Republican party in the states of the former Confederacy. What was called for, in short, was a series of political adjustments as delicate, as complex, and as subtle as any that have been carried out by an American President.

Such a political operation would have taxed the imagination of anyone; it was quite beyond that of Rutherford B. Hayes. His diary, edited by T. Harry Williams and printed in the form of the original, makes very good reading and is well worth the expert work Professor Williams has put into it. We have a week-by-week account of the administration as well as an engaging picture of social life at the White House. But above all, we get a good close look at the mind and personality of a nonpolitical politician.

Hayes was a man of good intentions, a bit too aware of his own rectitude, but very anxious to do the right thing. “With good health and great opportunities,” he wrote on his fiftieth birthday, “may I not hope to confer great and lasting benefits on my Country! I mean to try.” Given a situation that was clearly defined, he could be firm and effective. He vigorously defended his Presidential prerogatives against Congressional usurpation, calmly vetoing vital appropriation bills when unrelated amendments were tacked onto them by the Democratic majority. But that sort of firmness is hardly the test of true political resourcefulness, nor could the really important problems Hayes faced be resolved in any such simple way. They required hard thought and a careful balancing of alternatives, which was just the sort of responsibility Hayes instinctively avoided. When Southern Republicans attacked him bitterly for the policy he was following in the South, Hayes could strike a neat but quite artificial balance in his own mind between their anguished fears and the hostility currently being shown him by the Washington bar for his appointment of Frederick Douglass as Marshal of the District of Columbia. “If a liberal policy toward the late rebels is adopted,” Hayes noted smugly in his diary, “the ultra Republicans are opposed to it; if the colored people are honored, the extremists of the other wing cry out against it. I suspect I am right in both cases.” The cases were in no way comparable, and he should have known it. One involved a basic political commitment; the other, little more than a charitable gesture made to a distinguished Negro leader.

It was as though the very act of keeping a diary somehow helped protect Hayes from the need to think things through. Having once written down his good intentions, he seemed relieved of the burden of planning how they would be carried out. With satisfaction he notes the removal of troops from Louisiana and South Carolina and the pledges by the governors and legislatures to observe the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. He concludes: “I am confident this is a good work. Time will tell.” But not a word, here or later, on just how the pledges would be enforced. There are no real sanctions on performance, though anyone might foresee the difficulties that even the most sincere governor would have in the face of strong local opposition. So of course Hayes was deeply shocked when the news reached him eighteen months later that Louisiana and South Carolina were not keeping their promises. Gravely he wrote, “By State legislation, by frauds, by intimidation and by violence of the most atrocious character colored citizens have been deprived of the right of suffrage—a right guaranteed by the Constitution, and to the protection of which the people of those States have been solemnly pledged.” But he felt no personal responsibility; that had all been discharged at some point along the way. The fault now lay elsewhere.

Advertisement

It was in much the same spirit that Hayes refused to think through the problem of civil service reform. An honest and efficient government service was all very well, but the party as then constituted was heavily dependent on Federal patronage. It never occurred to him that an alternative base would have to be carefully prepared, and that it was perfectly possible in the meantime to bargain with the system. Patronage appointments need not rule out a reasonable level of efficiency and honesty in the government. But Hayes reduced the whole problem to a simple moral syllogism: “Let government appointments be wholly separated from Congressional influence and control…and all needed reforms of the Service will speedily and surely follow.” But nobody seemed willing to support such simple Spartan discipline, and Hayes righteously observed: “Impressed with the vital importance of good administration in all departments of Government I must do the best I can unaided by public opinion, and opposed in and out of Congress by a large part of the most powerful men in my party.” They were all so perverse, and they persisted in making things so complex. But that was hardly his fault.

By 1879 it was only too clear that nothing was going to come of the optimistic plans with which Hayes had entered office. The Democratic party in the South was more strongly entrenched than ever; little progress had been made in reforming the civil service; and the position of the Negro had deteriorated steadily. In deep self-pity, Hayes now wrote: “I am heartily tired of this life of bondage, responsibility and toil. I wish it was at an end! I rejoice that it is to last only a little more than a year and a half longer.”

When he left the White House, Hayes cut himself off completely from further involvement in national or state affairs; unlike most ex-Presidents, he made no further effort to influence either his party or his country. When he reminisced, it would be about his years in the army, not those he had spent at the head of the nation’s affairs. Hayes liked the idea of being President, but the office itself gave him few satisfactions. He was neither sensitive nor responsible to political pressures; he had a special capacity for shutting them out, and thus—unlike every successful American President—he denied himself to the country as a medium of communication. He found little joy in the exercise of power. He had no real urge to assume responsibility, to manipulate, to act, to make a difference in his time.

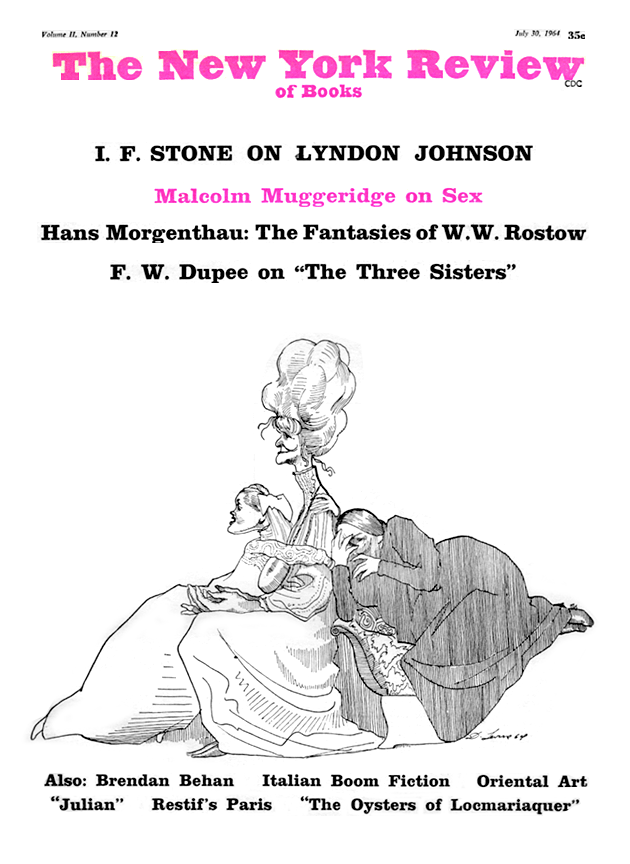

This Issue

July 30, 1964