Far back upstream, so very far back in the jungles of the Amazon headwaters that not even an anthropologist has visited them, live the Indians of Peter Matthiessen’s novel, At Play in the Fields of the Lord. Perhaps this little naked tribe is the last in the world untouched by civilization. In this story, they are touched and they fall, undone by the fascination their ultimate remoteness exerts on an assortment of Americans. The novel tells how this happens, how by airplane, outboard motor, by jungle trail, the Americans at last bring the first successful contact of the modern world to the savage Niaruna. At every stage of their various journeys, the Americans are tried to the extremes of danger by the piranha-infested rivers, by the filth and disease of jungle outposts, by the treacheries of the local satrap, their enmities for one another, by drink, drugs, madness, by machine gun and rifle and pistol fire, by spears, machetes, arrows, knives, fists, and broken bottles. They are tormented day and night by lusts, racial hatreds, and religious enthusiasms. Some of them die, but some, much altered, survive even the final catastrophe.

At Play in the Fields of the Lord is then, a novel of adventure, and it is, furthermore, to bring in at once the inevitable phrase, a good old-fashioned adventure novel. Peter Matthiessen is not horsing around with the elements of an adventure story, he gives us one straight. The perils of his adventurers, both physical and spiritual, are the elements of the plot, and his plotting is serious, responsible, and so engaging that it is likely most readers will not, need not, be aware in their excitement of how skillful and even ingenious this plotting is. In the first place, the characters assembled here are no accidental or coincidental group, no mere transitory names on a hotel register or a passenger list, come together by chance with their separate fates. Each of them has his own complicated necessity for the push through the jungle to the Niaruna tribe. Their relations with one another, also, are necessary. Their confrontations, quarrels, fights, loves, are each of them necessary stages in the plot. The perils, as I have indicated, are vivid and violent and frequent; but no single adventure seems to be there just for the adventure, for the sake of the thrill, nor because, if the danger is there, our tour must be exposed to it. The events grow out of one another, accumulating in intensity, until in the end every item of character has revealed itself in action, every gun that was hanging on the wall has been proven in discharge to have been no mere ornament, and the basic predicaments of the novel’s opening have proven themselves, in their long and complex working out, to have been the true omens of fate, necessity, and action.

Two antagonists compete for the Niaruna, each wanting to save them. One is a soldier of fortune, totally disenchanted and self-debauched, but because he is, of all things, a college-educated American Indian, he is determined first of all to find some “real” Indians, and then, finding them, he is determined to lead them in what might well be a successful military defense of their territory. The other is a missionary, one of an American group determined to save the Indians’ souls for Christ. The soldier of fortune, of necessity, becomes a god; the missionary, of necessity, loses his faith and becomes the tool of secular interests. And between them, in their exchanged roles, they destroy the tribe they have so spectacularly risked their lives to save.

To the reader, however, these designs of the plot are not forced in their unfolding. The book remains to the end an adventure story, with the scale and intensity of the action constantly augmenting. This is a considerable achievement. If, having finished this novel, you were to turn back to the beginning and read again a chapter or two, you would see how all this was brought about. The machinery, of course, is there. But it functions always as a related series of elements in a story. And this, I suppose, is what is meant by that phrase, a good old-fashioned novel.

In its presentation of this plot, the book is again, it must be said, good, and old-fashioned. Its manner is not so much that of any particular great novel of the past, rather it is like what we might imagine some very worthy “representative” sort of novel to be. There are, of course, descriptions of the strange locale, of jungle, river, sky, of the bars, latrines, bordellos, hog-wallows, and other sordid horrors of frontier villages: these descriptions are evocative, appropriate always in their places to some occasion for the thing being vividly seen—they are not travel notes. And, presumably, they are authentic. We have for this the authority of Peter Matthiessen’s own reports of his South American journey in his travel book, The Cloud Forest.

Advertisement

The characters are readily visualized, and always instantly recognizable as they come and go. In a long novel with a dozen or more leading parts, this is no small virtue; an old-fashioned virtue, perhaps, but a genuine one. Sometimes, for all their exotic traits, it seems we recognize them a bit too readily, as though they were type-cast. And we learn probably too much about them, the author has supplied rather more background for each of them than we really require, as he has supplied, in many scenes, a bit more information than necessary. He tells us more than anyone in the scene knows, more than he should know, more than we need to know. These somewhat too-well-known characters, together with one other familiar element, give even to the endless invention and excitement of all the things that happen, to the surprises and reversals of the plot, a very faint aroma of the familiar. Again, it is a good-old-fashioned adventure story.

The other and final familiarity is that of the theme, which is the inevitable destruction of what is innocent and primitive by those who believe, or pretend to believe, that they are out to save it. The hero, Lewis Meriwether Moon, Cheyenne Indian, in his final lone adventure is supposed to carry us into a theme beyond that, into the recovery of innocence. But this is a lyric episode, convincing as escape but not as much more than that. The burden of the story, for the endeavors both of Moon and of the missionaries, has been clearly stated in The Cloud Forest, when an American missionary he encounters “sadly concedes that the exposure of a primitive tribe to missionaries, however successful—because of the care, generosity, and devotion of the missionaries, the tribe is almost always benefited at the outset—is followed more often than not by its extinction, through the subsequent exploitation, mixed breeding, alcohol, and disease that arrive not with the advent of the Word but with civilization.” This is restated as familiar mockery by Moon and his partner in At Play in the Fields of the Lord.

But this book is not The Heart of Darkness, where confrontation with the primitive could induce a state of nameless terror in civilized men unable, in those days before 1914, to face their own underlying primitive bestality. Nor is it Black Mischief, where the confrontation is of two equally cruel and farcical societies. And it is not a fabled adventure into an imaginary primitivism, either, like Henderson the Rain King. Strange as it seems, there still are actual missionaries at work in the Amazon jungles. But real as they are, they are an anachronism. They seem long ago, of olden innocent times, like very good plots in adventure books.

If John Updike’s new novel, Of the Farm, has a plot it is a very sly one, rigged beneath the elegantly presented surface of three uneventful homely days. A young advertising man and spoiled poet named Joey Robinson brings to his mother’s Pennsylvania farm his new wife and her eleven-year-old son. His mother and his new wife quarrel, the young man remembers with regret his first wife, whom he has divorced, and their three children. He remembers his dead father. He quarrels with his mother, and with his new wife. He mixes up in his metaphorical mind his mother’s meadow which he mows and his wife’s body which is to him a highly figurative “terrain.” The young man registers these things in John Updike’s prose, neat, highly-polished, and self-conscious.

Now in cool air I kissed her and her face felt feverish. Fall, which comes earlier inland, was present not so much as the scent of fallen fruit in the orchard as a lavender tinge in the dusk, a sense of expiration. The meadow wore a strip of mist where a little rivulet, hardly a creek, choked by weeds and watercress, trickled and breathed. A bat like a speck of pain jerked this way and that in the membranous violet between the treetops.

His three women are not very clearly distinguished in this young man’s mind, and perhaps they are meant to remain undistinguished for the reader. Joey Robinson himself is an uncertain figure. Unless I am mistaken, the author’s intention is to present him as a selfish, irresponsible character, who has abandoned his family for the sake of a narcissistic sexual adventure, and has in effect also abandoned his mother. Certainly he is an unpleasant person often, with his unwelcome poetic rhapsodies on his wife’s anatomy, his constant word-for-word reports, as embarrassing as eavesdropping, of their private conversations: “Alone at last. Let’s fuck.” Yet it seems also that the narrator’s voice is supposed to be charming, with his lavender tinges in the dusk, his boyish frankness.

Advertisement

There is some duplicity here, and I do not pretend to understand it. Beneath this charm, beneath all this language, there seems to be operating a strange kind of jesuitical, almost secret Protestant evangelism, a subliminal maze of sex horror and Married Love. Joey Robinson is as eery an alter-ego as the ghost in “The Jolly Corner,” but whatever his bad secret may be, it is hidden from me.

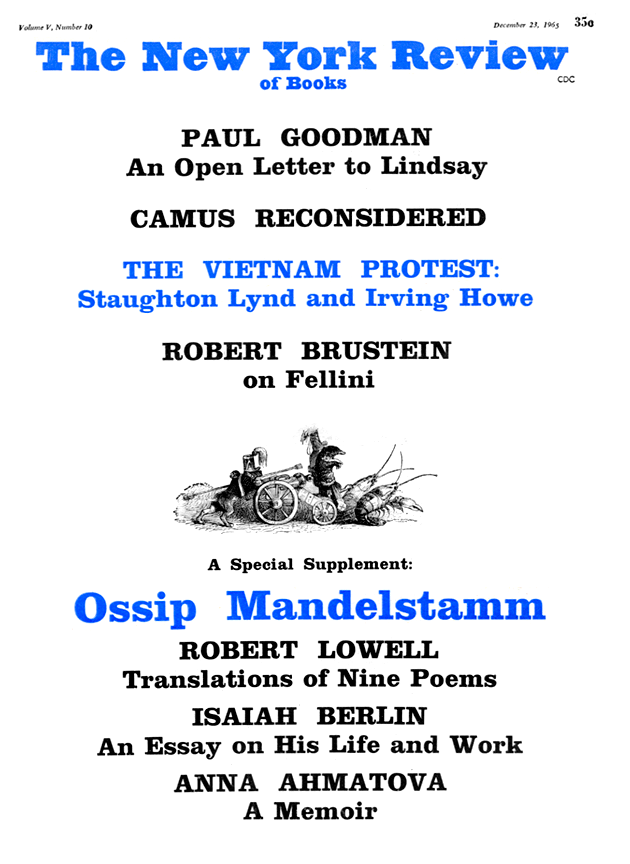

This Issue

December 23, 1965