The earliest of Ian Fleming’s penny-bloods were received with laughter and mock ecstasy. The wooden doll, James Bond, was garlanded with extravagant epithets: a streamlined figure full of gadgetry, carnivorous to the back teeth, this sado-masochistic private eye, daydream of male prepotence. (I collected such quotations when I was commissioned to write advertisements for Goldfinger.) There were reasons for the reviewers’ merry praise. The testicle-beating of Casino Royale seemed a pleasant change from the painless hurting and smug moralities of British body-in-the-library entertainment. Raymond Chandler, himself a product of an English “public school,” approved the novelty of Fleming’s shamelessness, the decision to describe the details of killing and torture and recognize their fascination; in a way, the new fantasy was facing facts.

Later the innovations were gleefully denounced as “sex, snobbery and sadism” by Paul Johnson in an influential New Statesman article but, in the early stages, they could be honestly if playfully welcomed—rather in the same way that Margery Allingham’s cranky whodunits had long been publicized as “for those wise men who like their nonsense to be distinguished.” Only when the Fleming nonsense was mass-produced for less well-educated citizens did the moral concern begin. The private joke had gone too far; it had been made public. An epidemic of parodies had already broken out, probably initiated by the Daily Mail’s “Flook” strip-cartoon. Soon every other British journalist was creating his own John Bind or James Bum, so many that I find I criticized another man’s Bond-parody for “breaking a slug on a wheel.” In his painstaking tribute to Fleming’s preposterous oeuvre, Kingsley Amis now writes forgivingly of the burlesques: “parodies have their laughter-value, but the laugh is partly affectionate.” Maybe, sometimes…

Anyhow, nobody’s laughing any more. Bond-books have become a theme for polemic, uncouth sex-snob accusations and counter-charges. Amis notices the development—and then joins in, denouncing Bond-haters as “old maids of both sexes.” The magazine, Private Eye, has retorted that Ian Fleming was a eunuch and Amis’s own work is “masturbatory.” This is all pretty coarse, but perhaps Amis asked for it. There is usually something wrong with a man who sneers at spinsters. What has gone wrong with Kingsley Amis?

The first bad sign is that he keeps saying “we,” as if determined to join some group or persuade others to join his. Here there is a touch of the slangy, soft-sell preacher, the kind who kills desire with his earnest commendations of teen-age petting, desperately stressing the cosy normality of his exotic cult: “We all lose our rag or blow our top with our foreman or manager or even our bishop. Don’t we? I know I do.” In just the same tone, Amis claims:

We rather enjoy being told by our wives and sweethearts that we’re smoking and drinking too much. It enables us to feel devil-may-care at little trouble or expense. A third way of feeling this is to drive too fast, and here too Bond is someone to look up to.

Naughty but nice, you see; nothing unnatural or highbrow about Bond-Amis; thank God we’re normal. The only possible response to this we-stuff must be personal. No, I’m sorry I smoke and drink too much, and I resent my wife’s criticisms; fast driving is the last thing I want to do. But Amis continues, confident of a nodding, smiling reader: “We don’t want to have Bond to dinner or go golfing with Bond or talk to Bond. We want to be Bond.” Strange. If I thought Bond was real, I should want to hurt him.

Does Amis really daydream of painful combat against the unregenerate Boches and haggish Lesbians of the international Bolshevik conspiracy? Does he relish the thought of pressing his lacerated body, still magically potent, against an equally battered female? Surely, all that he means when he claims to “identify” with Bond is that he enjoys fantasies of reward and applause. Amis once imagined, in a poem, girls forcing themselves upon him, each begging him “to sign her body’s autograph-book: Me first, Kingsley, I’m cleverest!”

Now from the corridor their fathers cheer,

Their brothers, their young men. The cheers increase

As soon as I appear.

From each I win a handshake and sincere

Congratulations.

Just so, in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the head of Union Corse begs Bond to accept a million pounds and marry his beautiful daughter; this unusual Corsican is glad that she should have been seduced by Bond, with his heroic reputation both as an Officer and as a Man.

But honesty compels me to confess

That this was all a dream which was indeed

Not difficult to guess.

Auden used to complain of this “dreaming of continuous sexual enjoyment or perpetual applause.” The younger poet sees no harm in it, partly because he can turn such dreams into pretty verse. But Fleming can’t do it. His treatment is grotesque, trashy. Why should Amis think it priggish to complain?

Advertisement

Because the Bond Books are popular, i.e., widely-read, and therefore Amis must gallantly defend them against minority opinion, bound to be snobbish. As an ex-teacher, Amis was “impressed by the motive for which every one of these readers reads them: pleasure. One volunteer is worth ten pressed men.” Surely that’s putting it rather strong? Amis belongs to a discriminating minority which chooses what to read and cares about it. Most people have other hobbies. If Amis had been a public librarian, he would know those readers who ask: “Have you got a nice romance, Mr. Lewis? Have I read this one?” Such readers are not sufficiently interested to “identify” with Bond; they are not seeking a potent pleasure. They have simply found the Bond series a reliable brand of cakemix, nothing to cause indigestion, all the right ingredients: erotic romance, exotic life-style, and the kind of violence known as “action.” It’s quite fair to call them sex, snobbery, and sadism—so long as you don’t assume that sex is as bad as the other two. That phrase caught on; currently, a Bond-cult paperback (containing an inane tribute from spy-master Allen Dulles) advertises “a world of sex, snobbery and—sudden death.”

There are other Fleming readers too—those who, like myself, have read or half-read all the Bond books not for pleasure but for business. There are the New American Library people printing 2,700,007 (get that, 007?) copies of You Only Live Twice, the Macmillan people offering America a lavish three-decker hardback, More Gilt-Edged Bonds; there is the Houston store-manager with his 2,000-copy dump table; and there are the manufacturers of “licensed-to-kill” rainwear. We have all helped transform this comical rubbish into a large-scale industry, furnishing profits, wages, and employment.

When I read Goldfinger, I thought Paul Johnson’s verdict too harsh, and I composed an advertisement thus: “SEX? Well, one of the three girls is normal.” (The other two were Lesbians.) “SNOBBERY? No, no, just good living. SADISM? Let’s call it schoolboy blood-and-thunder…” I thought this an admirable advertisement, and was quite surprised when the Manchester Guardian attacked it on moral grounds. Amis reacts to the three criticisms in much the same tone as my coy little ad—though he is, if anything, rather too severe on Fleming’s treatment of intersexual behavior: “vulgar and silly…a poor way of giving a reader a thrill.” These are very subjective judgments and personally I am not sure of any principle, moral or stylistic, which invalidates Fleming’s general use of sexual feeling. But the other two items, sadism and snobbery, Amis is too confused or diffident to discuss effectively.

Though he objects to amateur use of psychologists’ terms, he keeps dragging them in, almost as frequently as Fleming himself does: oedipal, transvestism, father-figure, the lot. He has a tedious theory that readers “identify” with fictional secret agents because they are oppressed by a conformist society and find the anonymous spy an easy-to-wear fantasy role. Even if this is true, it has no relevance to flashy, noteworthy Bond. Amis, who claims to want “cultural explanations for cultural phenomena” rather than psychological ones, in fact wastes many words on what his blurb-writer calls “sly Freudian hints”—and he never makes clear what he means by “sadism.”

If, by any chance, he means writing resembling that of Sade, he would have a good example in The Spy Who Loved Me, wherein the girl narrator describes a course of maltreatment at the hands of males, culminating in an attempted-rape sequence which I found rather erotic. Was I worsened? Amis assures us that no harm is done by Fleming’s descriptions of physical cruelty; the author is merely displaying the hatefulness of the baddies and the admirable courage of the goodies. Tom Paine wrote of Aesop that the cruelty of the fable does more harm to the heart than the moral does good to the judgment. But neither Paine nor Amis can be proved correct, except by laboratory experiment.

Amis offers passages from Mickey Spillane as examples of the real thing—“understanding by the real thing a kind of writing in which the reader is invited—pressingly—to enjoy the infliction of cruelty by a character with whom he supposedly identifies.” Fleming’s descriptions are different; they are not there for “fun” or “enjoyment,” but distill “a legitimate excitement and horror.” I cannot see the distinction. It’s fun to be excited; horrors are enjoyable. When does it start being sinful? In that rape scene, should I have identified with the girl or the rapists? Or must I wait until the arrival of Bond before I start this identification process?

Advertisement

Why should I? Bond, like a nervous British tourist at a bullfight, watches gypsy-girls fighting with knives for spectators’ amusement. In the same book, From Russia With Love, his jolly friend, Darko, keeps a girl chained naked under a table and throws her scraps. The heroes of old-time adventure tales, Captain Kettle or John Masefield’s Sard Harker, were strong-minded British seamen who would, if it was at all practicable, prevent such exhibitions; if not, they would storm out, passing crisp warranted criticisms of the local customs. Captain Kettle held that the Stock Exchange was sinful; but he was capable of working for crooked share-pushers, until he found they were dragging England into an unnecessary war. “What’s England to you, Captain?” “It’s the place where I live when I’m at home.” Yes, indeed. Compare Bond-Fleming’s grotesque assumption of all-round British superiority (“patriotism, mid-20th-century style,” says Amis), the belief that our spies are the most efficient, devoted, and self-sacrificing in the world (“It is perhaps the public school and universities tradition,” explains one of Fleming’s inane Russians), the belief that England is the essential target for foreign plots because of a system of inexpressibly lovely values involving the royal family and an ability to treat a West Indian as a Scots laird treats his head stalker: “authority was unspoken and there was no room for servility” (Live and Let Die).

This melange of class and race snobbery is not, of course, mid-twentieth-century at all. It is a hangover from imperialism, and many old imperial pop writers did it better. Even Brigadier Gerard might have blenched at Enrico Colombo (For Your Eyes Only) kissing Bond and saying: “Ah, the quiet Englishman! He fears nothing save the emotions! But me, Enrico Colombo, loves this man and he is not ashamed to say so!” Amis claims that Ian Fleming belongs with “those demigods of an earlier day” but also that he brings to the story of action and intrigue “a sense of our time.” Quite carried away now, Amis closes his tribute with a Churchillian thump: “he leaves no heirs.” Never mind. Plenty of Fleming’s forerunners survive on dusty shelves. Sax Rohmer’s Dr. Fu Manchu will serve for Dr. No; there are the Martian-Nazi-Satanist fantasies of Denis Wheatley. When these pall, Amis must try the boy’s comics.

One thing at least Amis and Fleming have in common. Neither is much good at non-fiction. One of the world’s worst travel-books was Fleming’s Thrilling Cities. “Racy, hairy-chested,” said the Oakland Tribune. “Girls, girls, girls,” said the Denver Post. Trotting about the globe, from one air-conditioned hotel to another, the poor old thing noted the menus and the sauciest voyeur-tourist-traps, a chat with a geisha, female mud-wrestling in Hamburg, transvestite performers in Berlin, a sado-masochist bar in New York—“it would be fun to go and have a look.” His factual information came from local journalists, like Dick Hughes and Tiger Saito in Tokyo; but he hadn’t the skill to record it straight without being a bore. When secret agents Dikko Henderson and Tiger Tanaka tell James Bond the same things in You Only Live Twice, the dramatic structure gives the material some point. Amis thinks this book “horrific and haunting in a way none of the others are, but travel-book material intrudes.” Surely not. The local color is rather well applied, but the book is horrific and haunting only to the degree of a Grimm fairy tale: “and the wicked stepmother was put in a barrel of nails and rolled downhill.” The idea is nasty, and children can horrify themselves by brooding on it; but the author can’t be seriously applauded for his skill in execution.

Fleming toned down the cruelties, nationalism, and snobbery until in his last book, The Man With the Golden Gun, he had produced an innocuous run-of-the-mill adventure story of 1911 vintage. No nonsense about Bond saving Western civilization. There’s a girl’s body on the railway line and an attractive but flawed villain whom Bond is too decent to shoot while he’s wounded. “Quite the little English gentleman!” sneers the rogue. That’s more like it. I can identify now.

Amis objects to Fleming taking note of his critics’ moral strictures. Yet this is quite a well-established social dialogue. Roosevelt was capable of advising a popular writer to introduce a Jewish hero, and Dickens accepted exactly the same counsel over Fagin and Riah. Everyone knows that there is a danger in the creation of class and racial stereotypes by irresponsible fantasists, even if they are as talented as the creators of Slackbridge and Othello. One of Fleming’s vices, which might have been brought to his attention, was that he encouraged the belief that none but the British leisure classes stand between us and the Queen’s enemies, roughly equated with anti-Christ.

He has created a secret agent who succeeds only though his prowess in leisured-class sports, golf, baccarat, skiing, food-selection, and underwater swimming in expensive tourist resorts—all of them, admittedly, rather well described. The Bond figure has also been equipped with the hair-style, clothing, and mannerisms characteristic of the most repellent type of Oxbridge student, regular officer and Conservative candidate. Amis objects to recent Bond movies not only for employing Sean Connery (a man of the wrong class!) but for burlesquing the original. Amis doesn’t want to boo the villain, like an adult; he wants to identify with the hero, like a child. Why? Because certain other English writers have made a fetish of “maturity” and Amis aims to counter them. Like so much of this discussion, the argument has precious little to do with the abilities of poor Fleming. With those movies we are back to square one, mirth and parody. The non-bookish masses are not crazy. They have never taken James Bond seriously and there is no reason why we, the bookish minority, should do so. Bondo-san is a straw dummy to be cheered or pelted, shouldered or burned, in aid of various causes. In himself, he is trash.

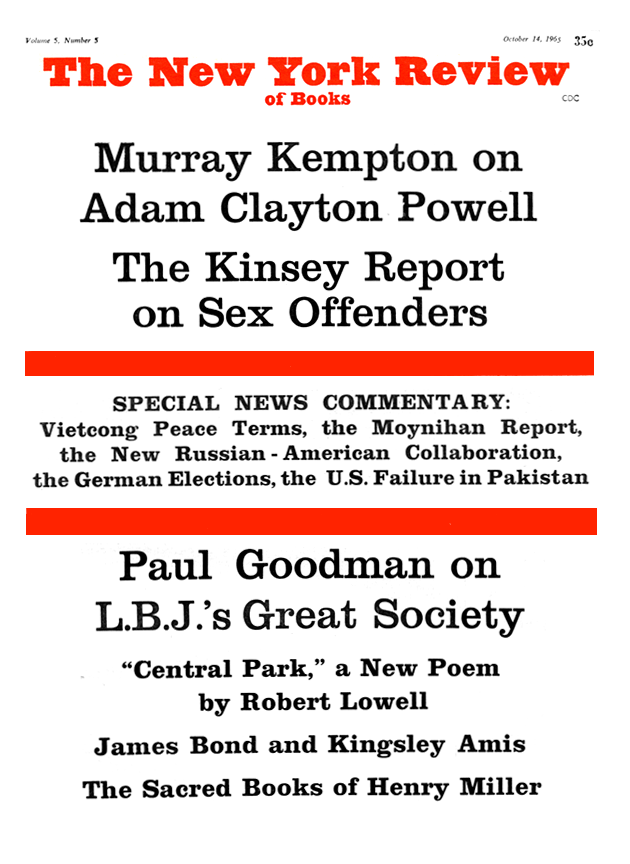

This Issue

October 14, 1965