During the newspaper strike in New York The New York Review presents the following articles from the foreign press and from our own correspondents.

Paris

The effects of the war in Kashmir have not all been bad. The crisis has now brought about diplomatic cooperation between the United States and Russia at the United Nations. And it has shown that when confronted with a dramatic Asian problem involving China, Washington can act with a cool and prudent confidence. But reassuring as these developments may be for the future, they do not outweigh the enormous risks created by the situation in Kashmir, with its dangerous combination of Asian nationalisms and Communist strategies, its Soviet Hinduism and its Maoist Muslimism. If conflict spreads in this part of Asia, the situation could “escalate” beyond the control of the most clearheaded leadership. The Russians, Americans, and French now agree that the Chinese are hoping that the present disputes involving India, Pakistan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia will all eventually enlarge and interlock, advancing Chinese ambitions. To thwart this supposed Chinese plan, it is now all the more important to find a solution in Vietnam.

What is France’s position? From August 1963 onward, it seemed that France—i.e., General de Gaulle—wanted to be of help in arriving at a Vietnamese settlement. But at his press conference on September 9th, following the outbreak of the Kashmir war, De Gaulle made it clear that his views have changed. He now thinks that France can do no more than wait to join with the other Great Powers in a Vietnamese intervention that will take place in the fairly distant future. Nor does he still believe that a solution to the Vietnamese problem must come from the Vietnamese themselves. This is a distressing reversal of his policy of two years ago which was based on the very principles of “non-interference” by foreign powers and free determination by the Vietnamese, that he now renounces. The man who once argued against foreign intervention would now multiply the intervention by five. This is a strange disavowal, the death of a hope.

But it must be said that De Gaulle’s skepticism finds some justification in the apparent hopelessness of the situation. This can be summed up by the two words constantly reiterated by the members of the North Vietnamese delegation that visited Paris earlier this year at the invitation of the French Communist Party: Guerre Longue. The delegation’s visit was politically significant; one of the most influential members of the Hanoi Communist Party, Le Duc Tho, met with the “revisionists” of the party most loyal to the Soviet line. But the visit did not produce the results that might have been expected in view of the “understanding” attitude of the French authorities and the interest it had aroused among the Americans. It occurred during a period when Hanoi was stiffening its position, probably because the efforts of U Thant and the Algerian delegation at the United Nations to act as intermediaries between the U.S. and North Vietnamese had met with little success.

It seems obvious that the channel between Washington and Hanoi is not the most propitious for a political settlement in Vietnam. Apart from the passionate antagonisms which trouble relations between the two countries, two grave misunderstandings make a dialogue futile for the present. The first of these concerns the facts: Washington insists that it is “retaliating against aggression” from the North; while Hanoi professes a policy of “non-intervention” in the South. Serious discussions are impossible when both sides refuses to accept the existing reality, namely that the war is fundamentally a southern uprising which Hanoi neither instigated nor inspired, although it has strongly supported it and supplied it with troops.

The second misunderstanding is even more serious. In Washington as well as Hanoi, there is talk of “returning to the Geneva accords.” But these words are used to describe completely opposed political aims. In Washington the Geneva accords are still interpreted as they were by Dulles and Diem—that is, as the basis for a partition permitting the consolidation of an anti-Communist state, a South Korea. Hanoi considers only the provisional nature of the partition and emphasizes that the accords held out the possibility of early unification under the auspices of the North.

The most important effect of Undersecretary of State George Ball’s visit to Paris this summer was to show that even if some members of the American administration are concerned with clarifying the conditions of a political settlement, they are not yet in a position to make their views prevail. First because they have not been able to define a serious alternative to the MacNamara strategy. And second because Mr. Johnson has not ruled in their favor. (The recent conference on Vietnam at the University of Michigan was called to consider the question of alternatives but has aroused only small interest in official circles even among “liberals.”) We can well believe the President is weary of this war, that he would like to be done with it. But it is apparent that the White House braintrust does not yet have an accurate idea of the sacrifices a “compromise” would entail.

Advertisement

There have been some interesting gestures toward “de-escalation” in the last few weeks. First, there were the indirect announcements to Hanoi made by various American spokesmen, and notably by Mr. Arthur Goldberg. Their message was that the bombardments in the North would be stopped or at Jeast considerably mitigated if only a portion of the 325th North Vietnamese Division were withdrawn from South Vietnam. Was this merely an attempt to embarrass Ho Chi Minh, who does not acknowledge having sent troops south of the 17th Parallel, or is it a sincere offer? We cannot say. Then there was, in Saigon, the appointment of Mr. Lodge’s aide General Lansdale, formerly one of the masterminds of Diemism and of the policy of “strategic hamlets”; but Lansdale is expert enough in psychological warfare to understand the political disasters suffered as a result of the pounding attacks on South Vietnam.

And finally there was Senator Mansfield’s proposal, on September 1, of a five-point program which sums up most of the concessions made in the last three months by Mr. Johnson and Mr.Rusk: cease-fire, amnesty, self-determination of South Vietnam, evacuation of all foreign troops, possibilities for re-unification. There is much emphasis in Washington on the fact that the President had given his assent to the Mansfield program. For that matter the program hardly goes beyond Mr. Johnson’s own declarations of the past few weeks.

Aside from the opposing motives mentioned earlier, the most apparent point of discord between Senator Mansfield’s “five points” and Phan Van Dong’s “four points” of April 1965, is that for the North Vietnamese, the NLF (or Vietcong) is the only legitimate representative of South Vietnam. For their part, the Americans now acknowledge the de facto existence of the Vietcong but refuse to let it take part in discussions except as a subsidiary of the Hanoi regime. This helps to defeat the possibility of successful negotiations before they start.

To be sure, this is not the only obstacle to transforming the military conflict into political discussions. The other obstacle, of course, is Peking. But Paris as well as Washington has a tendency to exaggerate its importance. It seems, however, that on this point André Malraux’s mission to China was not completely discouraging. Of course anyone who expected that the author of Les Conquerants would return from China with Peking’s agreement to mediation could only have been disappointed. But if Malraux’s purpose was to gauge Chinese intentions, he elicited some interesting answers. Although Mao Tse-Tung avoided discussion of Vietnam, Chou En-lai and Chon Yi confirmed that Peking would hold to a “hard line.” In their view, the United States must pay for its aggression by a clearcut defeat. Since they think it natural that they will eventually negotiate with Washington on Formosa anyway, they hope that Vietnam will pursue the war until the Americans are forced to withdraw. But the two Chinese leaders reportedly added that although this was their own view, it counted for less than the views of their Vietnamese brothers, both in Hanoi and especially in the N.L.F. The question was up to Vietnam and must be decided by its citizens; if North Vietnam and the Front could achieve their ends by negotiation, China would have no objection.

Were these purely formal remarks? Most western observes think so. They are wrong. For in the last few months the Chinese have been able to estimate the intensity of Vietnamese national feeling They are now more careful not to encroach on an area which does not belong to them. Communism’s evolution toward polycentrism is also an element here. We cannot foresee tension between the Chinese and Vietnamese communists. But the West seriously underestimates the specifically Vietnamese character of the struggle going on in the ricefields; and there is far too great a tendency to see the Vietcong and their northern allies merely as pawns in a Sino-American conflict. Of course Peking can exert pressures on the situation. But it is all the less powerful because its participation in the war is negligible and the Vietnamese national tradition is strong.

No matter how much one studies the question, it is impossible not to be impressed by the vigor of Vietnamese nationalism. This is why, in any peace explorations, it is of the greatest importance to consider the intentions of the Vietnamese forces, the Hanoi government, and the Liberation Front of the South.

Advertisement

The latest declarations from Hanoi are as intransigent as those of the Chinese, notably that of Pham Van Dong on September 2nd. It envisages nothing less than victory. But at the same time, all the North Vietnamese spokesmen who have been contacted insist that the “four-point plan” enunciated by the Prime Minister in April remains the “basis for discussion.” Of these four points, three—self-determination, no foreign intervention, possible reunification—are already accepted in Washington. There remains the fourth, the affirmation that any solution must “conform to the program of the NLF, the authentic representative of South Vietnam.” But the Front’s program (independence, socialism, and neutralism) is not seriously at odds with the stated American position.

One previous attempt at settlement has remained generally unknown to the public. It could be repeated tomorrow if the same conditions were to exist once again. On May 18, 1965, after the bombing of the north had been suspended for five days, the Hanoi envoy in a neutral capital told the government to which he was accredited that the time had come to make clear that acceptance of Pham Van Dong’s “four points” was not a necessary pre-condition to negotiation with the Americans, and that the recognition of these “principles” would open the way to a settlement. That very evening, the bombardments resumed and the move toward negotiations was abruptly halted. But it is clear that it would be reinstated if the bombing of the North were to stop again. If the Hanoi spokesmen are once again making the evacuation of U. S. troops a condition of official talks, this attitude contradicts their continual reference to Mr. Dong’s “four points.” In fact, it seems that the acceptance of only three points would be sufficient to get the process of peaceful settlement underway: the “principle” of independence; the desirability of unification; and the legitimacy of the Liberation Front as representative of at least a part of South Vietnam.

Recent proof of this can be found in Ho Chi Minh’s replies to questions put to him in writing by Philippe Devillers (author of the History of Vietnam); his answers appeared in Le Monde on August 15th. Speaking of the cessation of the bombardments of the North and of the evacuation of American troops from the entire country, Ho declared that only the first of the two demands were “immediate.” The withdrawal of American troops was presented as an objective, not as a preliminary condition. For that matter, the Hanoi leaders know the situation better than the men in Peking, and they have good reason to believe that the American expeditionary force cannot be conquered by persuasion.

Will the key political decisions be made by the National Liberation Front in the South? The NLF is the most interested party. It is the protagonist in the war, and draws its support from a population now suffering an intolerable battering. This will become even worse in October with the arrival of the dry season awaited by the American Air Force. But the NLF has been extraordinarily silent. The Algerian FLN was better at mobilizing political sentiment.

Still, the South Vietnamese Front can be approached discreetly. Three French diplomatic missions are in permanent contact with NLF agents in Europe, in Africa, and in Asia—a fact which arouses more than a little disapproval in Washington. From these sources we learn that the Front remains strongly attached to the idea of southern autonomy, and that its objective is to rapidly organize a truly representative democratic government in Saigon, a government which would have to be a coalition. The Front would be ready to implement self-determination in the South by carrying on negotiations with the North that would be an exchange between equals.

Does not a Vietnam settlement lie here, rather than in bitter negotiations between Americans and North Vietnamese? It is apparent that there are three levels on which peace may be sought: among the Great Powers: between Hanoi and Saigon; among the South Vietnamese. No enduring solution can disregard any of these three possibilities. But priority should be given to the democratization of power in the South.

It is obviously unlikely that Ambassador Lodge and Colonel Lansdale will create a pseudo-liberal and formally democratic government is Saigon. But the United States can certainly allow discussions to begin among the South Vietnamese in which the Liberation Front would play a primary part. Such a procedure would at least permit a return to reality; it would have the merit of basing any solution on the existing social and political situation—which is much more complex than is commonly believed. The NLF leaders know this better than anyone else.

Why does Washington insist on restoring peace in the South through the political intervention of the north, when it decries the North’s military intervention? A South-Vietnamese solution, chosen by the South Vietnamese themselves, must precede any larger settlement. The capacities of the South Vietnamese for political accommodation would surprise us, if only they were permitted to express them. It must not be forgotten that immediately after Diem’s ouster, the National Liberation Front leaders made an appeal to the generals of South Vietnam. Once again, Saigon turned a deaf ear. Yet it is at this level that the process of peacemaking could be set in motion.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Paris Nouvel Observateur.

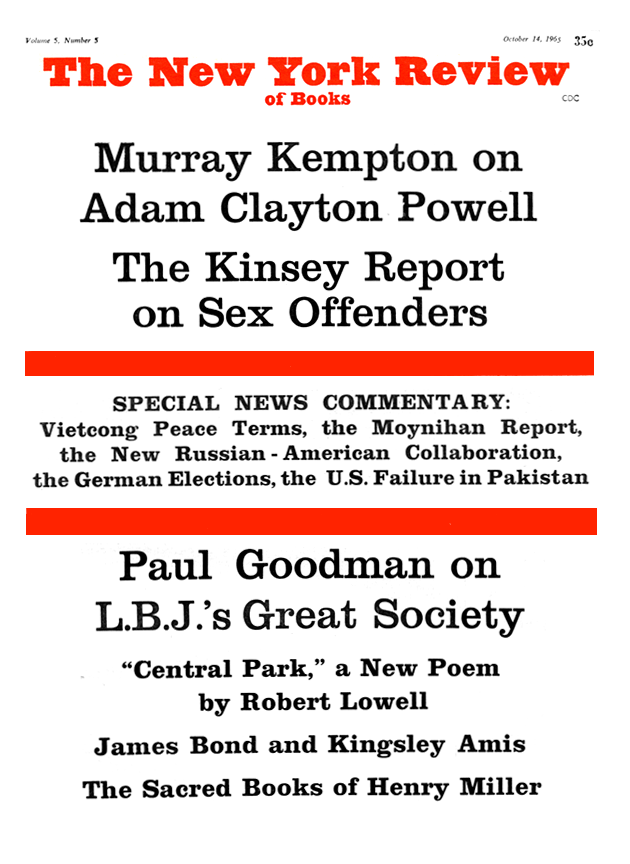

This Issue

October 14, 1965