All the apparatus of pornography is here—whips, chains, leather goods of many kinds, dungeons, costumes including masks, gowns that roll up in back like window shades, breakaway trousers, gags, and even a few items which are not in the traditional inventory. Poor O, the heroine, is beaten, branded, and punctured, exposed to every possible view, hideously violated, but for all this, Story of O is a little off center as a pornographic novel. Except for a stirring passage or two—the famous taxi ride, for instance, with which the novel begins—tumescence seems not to be the central issue, and may not be the issue at all. Rather, one is struck by an atmosphere of prestidigitation, of double and triple meanings that suggest an elaborate literary joke or riddle which extends even to the question of O’s authorship. Pauline Réage, except as author of the present book and of the preface to another, seems not otherwise to exist: None of her admirers claims to have met her, she has not been seen in Parisian literary circles, and it has been said that she is actually a committee of literary farceurs, sworn to guard their separate identities, like the pseudonymous authors of a revolutionary manifesto.

In any case, like Miss Réage herself, her characters too are more presences than people, disembodied for all their obsessive carnality; spirits or essences. It is a little as if an Indian temple frieze had been transposed to the porch at Chartres. Sex is all they think about or do, but physical gratification seems not to be what they are after:

O was happy that René had had her whipped and had prostituted her, because her impassioned submission would furnish her lover with proof that she belonged to him, but also because the pain and shame of the lash and the outrage inflicted on her by those who compelled her to pleasure when they took her, and at the same time delighted in their own without paying the slightest heed to hers, seemed to her the very redemption of her sins…. As a child, O had read a Biblical text in red letters on the white wall of a room in Wales where she had lived for two months, a text such as the Protestants often inscribe in their houses: IT IS A FEARFUL THING TO FALL INTO THE HANDS OF THE LIVING GOD No, O told herself now, that isn’t true. What is fearful is to be cast out of the hands of the living God…Oh, let the miracle continue, let me still be touched by grace, René don’t leave me.

We are, in this passage, in two worlds at once. One, obviously, is the world of Justine and her progeny, but in the other we smell the remains of John Calvin and behind him that lacerated troop of believers who, through their wounds and privations, hoped to achieve communion with their terrible but necessary God. Story of O is filed with the sense of sin, but not with the sort of sin which one might, at first, look for.

She felt as though she were a statue of ashes—bitter, useless, damned—like the salt statues of Gomorrah. For she was guilty. Those who love God and by Him are abandoned in the dark of night, are guilty, because they are abandoned.

ABANDONMENT AND ISOLATION: These are the marks of sin. Grace restores communion and communion is the immolation, more or less, of flesh within flesh. Hence the frenzy with which Miss Réage’s characters endlessly crawl or plunge in and out of one another. It is all, one feels, a joke, an elaborate but very private parody, meant, for all one knows, to implicate Jacques Maritain with the Marquis de Sade, a beserk imitation of Graham Greene, a wicked joke at the expense of those who, in these times, would become one with the body of Christ. If it is not a joke, then it is madness, though not without brilliance and not without pathos.

In any case, it is skillfully done. The language is spare and elegant and, as Jean Paulhan of the Académie Française insists in his Preface (a Preface whose style is not unlike that of the novel itself) an air of “ruthless decency” permeates the book, a kind of spiritual breeze blows through it, flattening the perspectives and sterilizing the atmosphere between the reader and the events of the story. The whippings and beatings and the other tortures become somehow innocuous, drained of their power to terrify or excite or often even to interest the reader, yet they retain another kind of strength: They have the power retained by legendary actions to suggest analogical meanings. Pauline (Paulhan?) Réage, whoever she, he, or they may be, is surely perverse and may indeed be mad, but she or he is no fool and is as far as can be from vulgarity.

Advertisement

YET THE NOVEL, quite apart from its deliberate mystifications, raises questions of a secular sort, so to speak, of sexuality as such as distinct from its spiritual implications, with which it seems unwilling to deal. O, the eponymous heroine, is a fashion photographer who allows René, her lover, to incarcerate her for a period of two weeks in Roissy, a château a conventional item of pornographic bric-a-brac near Paris. Here, though she is free to leave at any time, she is expected, while she stays, to submit to the sexual requirements of the company of masked gentlemen who inhabit the place. Their demands are predictably outrageous and O is made to gratify them in silence, no matter how humiliating or painful. O submits willingly and thus, through her suffering, proves to René, but to herself also, that she loves him—belongs to him—and he responds by confirming, from time to time, as it pleases him, that he loves her too. O, we are told, had once been a proud and stubborn woman who had taken a kind of pleasure in rejecting her many suitors. Why then does she put up with such nonsense from René, a young man of no special qualities, and from his anonymous and whimsical friends? The question, once separated from its bizarre surroundings, is, of course, naive. The answer which we are meant to infer from the novel—which is the psychological point of the novel—is that this is the nature of women: that O is no more than an extreme, or legendary, case of the everyday housewife who, having once renounced her freedom on behalf of certain domestic arrangements, thereafter despises her former independence, rejects the power that her sexuality once gave her, and in permitting herself to be tamed and humbled finds the meaning of her life in the conditions which define and eventually depersonalize her. It is hardly different from the case of the nun or other holy woman who, through self-mortification, claims communion with stronger and more comforting agencies than had been available through her own, independent means. Whether we like it or not, Miss Réage seems to say, female sexuality expresses itself through a kind of progressive annihilation of self. O will be happiest when she achieves the condition which her name implies: when her sex becomes indistinguishable, so to speak, from its surroundings.

According to one’s prejudices, one may accept her thesis or not. At any rate, it is arguable. But when it comes to her male characters, Miss Réage is much less satisfying and one begins to suspect her of indifference or ignorance. Why, one wonders, should the men put on their ridiculous costumes, leave their regular occupations, and for days on end devote themselves to terrifying and caressing the ladies who fall into their hands? In the case of René, who has a job of some sort which he more or less attends to, though which he is always ready to interrupt in order to arrange a beating or a mutilation for O, perhaps the answer is not so difficult. Men do, after all, neglect their work or other pleasures for the sake of sexual passions that occasionally overcome them. But when it comes to Sir Stephen, René’s older half-brother, a glowering brute, a French nightmare of grizzled English virility, with his chains and his riding crops, to whose superior cruelties René eventually delivers O, then we are taken beyond analogy into fantasy. This is not to say that sexual sadism on the part of males is such an odd notion, but Sir Stephen is made to carry things too far. It is not his sadism that makes Sir Stephen contemptible as a fictional invention; it is the frenzy with which he sustains it, hour after hour, day after day. Sir Stephen in his constant ardor is no more than a motiveless maniac. For all the thrashings he administers, he is a mere prop or servant, a contrivance to speed O toward her apotheosis. One suspects Miss Réage of a degree of sadism of her own for having invented such a rude parody of male sexuality.

O SUFFERS HER DEEPEST and thus her most satisfactory humiliation not at the hands of her gentlemen tormentors but, predictably in this aggressively female novel, at those of women. Partly at the request of Sir Stephen, whose curiosity is piqued by the thought of such a liaison, O falls in love with a model named Jacqueline, an impassive and stupid lady who, though she allows herself to be seduced, finds O’s account of the mysteries of Roissy both ludicrous and disagreeable. In the terms of the legend, she is the unreconstructed pagan, the frivolous peasant to whom the martyr’s devotion is incomprehensible. She is the last spur to O’s ruin, which is to say her transcendence.

Advertisement

In the final episode, O is made to wear the mask of an owl and, with a cowl of feathers but otherwise naked, she is led on a dog’s lead, attached by iron rings to what Miss Réage delicately calls her belly, to a courtyard within a sort of cloister. There on a flagstone terrace, where a dozen couples in low cut dresses and white dinner jackets are dancing, O is led to a stool and seated, her back against a wall, her hands upon her knees in the manner of an ancient statue. Like an object made of stone, she is, as the evening progresses, investigated by the dancers who surround her. But no one speaks to her directly. “Was she then of stone or wax, or rather some creature from another world, and did they think it pointless to speak to her? Or didn’t they dare?” One would think that some at least would have gone home, their evening ruined by such a spectacle. One dancer, a drunken American tourist, was moved to laughter by the event, as who, in his embarrassment, might not be? But “grabbing her he realized that he had seized a fistful of flesh…and suddenly sobered up…O saw his face fill with [an] expression of horror and contempt…. he turned and fled.” And many will, perhaps long before this final episode. Still, one is sufficiently mindful of the power of ancient gods and enough impressed by the talents of Miss Réage to feel that the laughter, to say nothing of the horror and the contempt, is perhaps uncalled for.

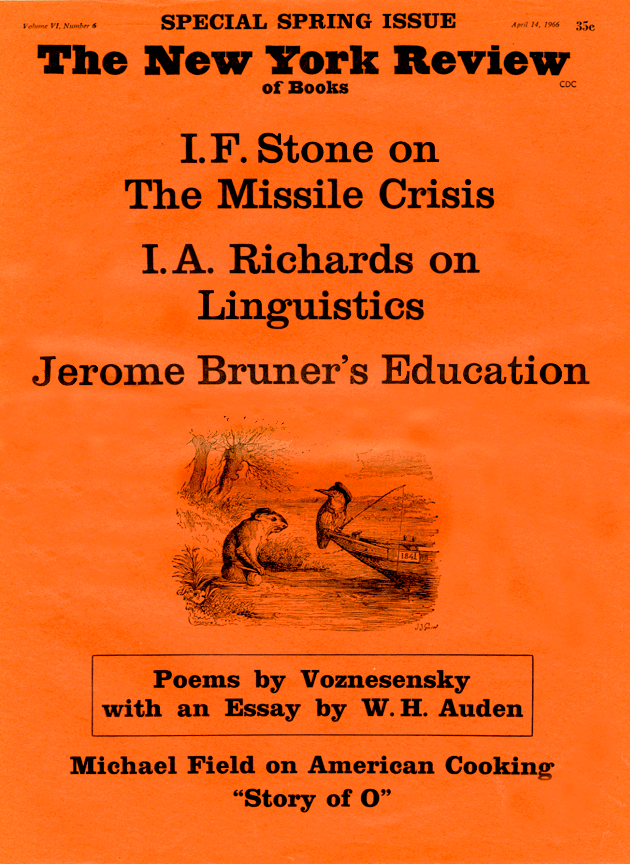

This Issue

April 14, 1966