“Derivations,” they used to be called in school. “Pryce-Jones, give me a word that derives from the Hungarian.” Silence. “I know, sir, ‘coach’.” “Why?” Silence. “I know, sir, isn’t it from a town called Kocs?” “Good boy. And now tell me where ‘marmalade’ comes from.” “Isn’t it from Mary, Queen of Scots, when she was sick: Marie malade. Like that square in London, the Elephant and Castle, from ‘the Infanta of Castile’.” “Don’t show off. You’re wrong anyway. ‘Marmelada’ is Portuguese, from ‘marmelo,’ a quince.”

The afternoon would have drowsed (perhaps from OE drusian) less uncertainly, had Dr. Onions completed his work in time. Not that other etymological dictionaries are to seek. There is the great dictionary of Skeat, and, more recently, Eric Partridge, in various books, has given a fillip to the study of word origins. But Onions, who died in his nineties last year, was a famous lexicographer with the resources of the Oxford University Press behind him. He may be expected, therefore, with the able help of his collaborators Dr. Friedrichsen and Mr. Burchfield, to have the last word.

More than 38,000 last words, indeed: from “aardvark” to “zymurgy.” With most careful scholarship he has traced the chronology of words to their origin, refraining from guesswork except when the guess is explicitly such. He gives the pronunciation, and at times he adds a fascinating piece of special knowledge, such as the connection of “runcible”—a pickle fork was called “runcible” before Edward Lear used the word at all—with the place-name “Roncesvalles.”

All the same, this industrious compilation is only a very partial success. It raises, first of all, the question, why compile a dictionary of etymology when most good dictionaries—and certainly the Oxford English Dictionary, on which Dr. Onions had worked for most of his life—cover the ground? The answer must be that the evolution of language, especially in matters of idiom, slang, exotic turns of speech, moves too fast for any dictionary to remain up-to-date. The interraction of local usages in different parts of the United States, in Great Britain, Australia, Canada, the Caribbean, will never be pinned down in a stately official dictionary. The first essential, then, for an etymological dictionary is up-to-dateness.

HERE DR. ONIONS FAILS. His entries are almost entirely confined to the conventional speech of England round about 1910. If you wish to find out why a Calypso is so called, whether “faggot” could mean anything beyond a bundle of sticks tied together (from the Greek phákelos), why “john” covers a field beyond the range of either the Baptist or the Evangelist; if you search for the origin of words like “stoned,” or “limey”; above all, if you so much as approach the bed, let alone the chaise-longue, you must look elsewhere for information.

He is not even very consistent. We are told that “fuchsia” stems from Leonhard Fuchs, and “begonia” from Michel Begon: but how about parallel derivatives in other spheres? Is not “bilharzia” as good as “dahlia”? At times he plumps for a single usage, and that not the obvious one. There cannot be many people, for instance, for whom “placebo” means exclusively “vespers for the dead,” or “bingo” brandy.

Who, I wonder, uses an etymological dictionary? To be interested at all in the derivation of words requires a bent of mind shared only by the few. That few will have the kind of curiosity which stems from a good education. They will know that “duke” is the same word as “dux,” that “honesty” comes from the Latin “honestus.” But they will want at times to look up an oddity. What on earth are the origins of “hullabaloo,” “panjandrum,” “jabberwocky”? And, if they are accurate-minded, they will want to check the use or misuse of evasive words such as “expertise” by referring to its origins.

Dr. Onions is only intermittently useful here. Certainly, he was not compiling a dictionary of English usage, but at times his notes are so full that his silence at others seems the more surprising. Thus, under “panic,” he refers back to “Pan, name of a deity, part man, part goat, whose appearance or unseen presence caused terror and to whom woodland noises were attributed.” Indeed, throughout this area of the alphabet, Dr. Onions is pleasantly communicative. “Panopticon,” “Panorama,” “Pantechnicon,” “Pantaloon,” “Pantheist,” and “Pantomime” (but not “Pansy”) are informatively presented. A few pages on, “Philistine” has a model entry, to cover the allusive sense in which it was employed by Carlyle and Matthew Arnold, taking the allusion back to a sermon preached in 1683 at the funeral of a student killed in a riot at Jena, on the text, “The Philistines be upon thee, Samson!”

But elsewhere he can be extremely curt. For instance, one of the words which have long troubled word-mongers is “ghetto.” Dr. Onions, with no explanation, plumps in a four-line entry for a derivation from “Aegyptus,” without any mention of a more accepted derivation from “gettare,” to “cast in metal”: an avocation which gave its name to the Ghetto Nuovo, a center of Jewish metal-workers in sixteenth-century Venice. Again, when he comes to “avocado,” he says roundly that it was “substituted by popular perversion for Aztec ahuacatl,” though you will have to look elsewhere—the new Random House Dictionary, for instance—to discover the whole point of the matter: that the Aztec word means “testicle.”

Advertisement

IT WOULD BE UNFAIR to pick on such isolated examples without giving Dr. Onions credit for an immense range and a generally high standard of caution. The ordinary reader is unlikely to come often in contact with words like “forgatt” (a seventeenth-century term for the sidepieces of a glove-finger) or “dandiprat” (either a small coin or an “insignificant fellow”); but it is just such words which, once in a lifetime, need elucidation. The former, we learn, comes from “fourchette”—because of its shape—and of the second Dr. Onions firmly says that the origin is unknown. Indeed, to turn these pages is to realize afresh how poverty-stricken is our usual vocabulary. There was a headmaster of Eton, some forty years ago, who used his classical knowledge to enlarge the language by such devices as ending a sonnet with invented synonyms: “Be off! Evade! Erump!” Similarly, Dr. Onions devotes much space to words like “exenterate” for “disembowel,” “jockteleg” for “clasp-knife,” and “owelty” for “equality.” We shall never use them: we are unlikely to meet them; but it is nice to know that they are there.

One of the pleasures of a dictionary is its dippability. That is why Grose’s Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue remains unsurpassed, though the Wentworth and Flexner Dictionary of American Slang runs it close. Here Dr. Onions is frankly hopeless. I judge him to have been a man of iron respectability, and certainly quite proof against the corruptions of American speech. The polite researcher into his pages will find little to offend. Even the single four-letter word admitted, “arse,” is defined as “fundament,” thus removing it as far as possible from the grossness of the body and giving a faint overtone of architecture or even theology.

What Dr. Onions likes is a good respectable word like “rape,” in the sense, let it hastily be added, of “any of the six administrative districts of the county of Sussex, England” in the eleventh century, with a reference to Dudo of St. Quentin, quoted in Migne’s Patrologia Latina. Or “screw,” “a mechanical contrivance of which the operative part is a spiral groove or ridge,” which whizzes backwards in time, through Scandinavian forms, to Middle High German, with a glance on the way at “scrofula,” which in turn looks askance at the Latin “scrofa,” a breeding sow, supposedly subject to that disease.

The trouble, of course, with such excursions is that they may or may not lead in the right direction. I notice, for one thing, that derivations from the Sanskrit, once all the rage, are now out of favor. Middle Dutch is much on Dr. Onions’s mind, and so is the Portuguese. But the truth of the matter is that word-origins are a form of cryptography, with the disadvantage that a cryptogram can be proved or disproved as a matter of first-hand experience, whereas a derivation can only be ventured.

IT DOES NOT MUCH MATTER, perhaps. I can call my enemy a filthy bastard without stopping to consider the implications of Old English fylp, Old High German fulida, and Old French bast, which would strongly suggest that my enemy’s mother had once met a mule-driver. But Dr. Onions approaches his subject in a Dryasdust manner. The picturesque has little charm for him, the conjectures of others little validity. In a skill of total exactitude this might be admirable. But the truth is that nobody really knows, say, the origin of “ghetto.” In the circumstances, Dr. Onions’s take-it-or-leave-it brevity sometimes looks a trifle bald.

This is the sadder because most of us not only use very few words but take small interest in words as such. It is as though the improvisations of Joyce and his few disciples had overstrained the language. We have no Lylys or Sir Thomas Brownes among us any more, to set our imagination at the stretch by some ingenious trope or fancy. Language is not even utilitarian—the useful concept of Basic English, by which anybody could use our tongue by learning a few hundred words, never came very far. On the contrary, to use words accurately, or unexpectedly, is generally frowned on nowadays. It is not long since Mr. Tom Wolfe was an object of censure for using the participle “infarcted” (from a verb on which Dr. Onions turns his back).

Advertisement

Thus, although these 1,000 pages contain an impressive store of learning, I shall turn to them less often than to the racier wordbooks of Eric Partridge or Ivor Brown; I shall not read in them as I might read in Grose, and I shall not abandon for them the pioneer work of Skeat. Eximious they may be, but not immarcescible.

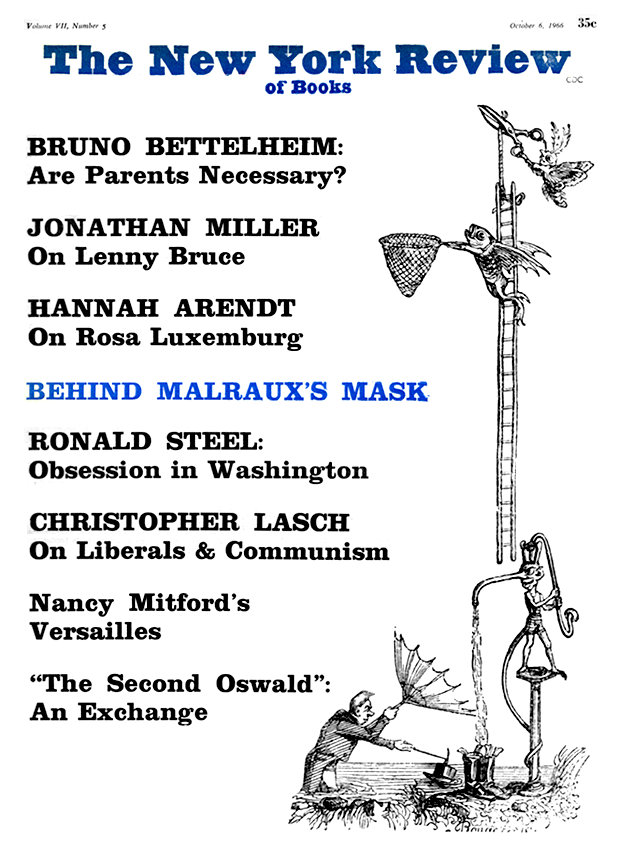

This Issue

October 6, 1966