To My Wife

Dear little insect

whom for some reason they called fly1

this evening almost at dark

while I was reading the Deuteroisaiah

you reappeared beside me,

but without your glasses

you could not see me

nor could I without their glitter

recognize you in the dusk.

Without either glasses or antennae,

poor insect with wings

only in imagination,

a broken-backed bible but not all that

reliable either, the black of the night,

lightning, thunder and then

no storm. Or was it that

you had left so soon without

speaking? But it is ridiculous

to think you still had lips.

At the Saint James in Paris I shall have to ask

for a “single” room. (They do not like

unpaired guests.) So too

in the false Byzantium of your Venice

hotel; then at once to seek out

the telephone girls at their switchboard,

ever your friends; and off again,

the clockwork spring run down,

the longing to have you again, even if only

in a single gesture or habit.

We had planned a whistle

for the hereafter, a sign of recognition.

I try it out in the hope

that we are all dead already without knowing it.

I never understood if it were I who was

your faithful and distempered dog

or whether you were mine.

You weren’t like that to others—rather a myopic insect

not at home amid the chatter

of high society. How naïve

those smart ones were—not knowing

that it was they who were your laughing-stock

nor that they were seen in the dark and detected

by an unerring sense of yours, by your

bat-like radar.

You never thought of leaving any trace

of yourself by writing prose or verse. It was

your charm—and then my self-disgust.

It was my dread as well: to be afterwards

pushed back by you into the croaking

slime of the neoterics.

The self-pity, the endless grief and anguish

of him who worships the down here yet hopes for and despairs

of another…. (Who dares say of another world?)

“Strange pity….” (Azucena, second act).2

Your speech so scanted, so unwary,

remains the only one I am satisfied with.

But its accent is changed, its color different.

I shall get used to hearing or deciphering you

in the ticking of the teleprinter,

in the coiling smoke of my Brissago

cigars.

Listening was your only way of seeing.

The telephone bill is next to nothing now.

“Used she to pray?” “Yes, she prayed to St. Anthony

because he helps one find

lost umbrellas and other items

of St. Hermes’ wardrobe.”

“Only for that?” “For her own dead too,

and for me.” “That is enough,” said the priest.

The memory of your weeping (mine was double)

is not enough to extinguish your bursts of laughter.

They were, so to speak, a foretaste of your private

Judgment Day, never, alas, to happen.

Spring comes out with its mole-like pace.

I shall no longer hear you talk of poisonous

antibiotics, of the ache in your thighbone,

or of your goods and chattels that a crafty legalism

fleeced you of.

Spring comes on with its fat mists,

with its long daylight, its unbearable hours.

I shall no longer hear you struggle with the gushing back

of time, of phantasms, of the logistical problems

of Summer.

Your brother died young; you were

the unkempt little girl staring at me

posed in the portrait’s oval.

He wrote music, never published or performed,

now buried in a trunk or gone

for pulp. Perhaps someone is unconsciously

re-creating it, if what is written is written.

I loved him though I never knew him.

Except for you nobody remembered him.

I made no enquiries: now there is no point.

After you I was the only one left

for whom he ever existed. But we are able,

shadows ourselves—as you know—to love a shadow.

They say mine

is a poetry of unpertainingness.

But if it was yours it was someone’s:

yours, who are no longer form but essence.

They say that poetry at its highest

praises the Whole in its flight;

they deny that the tortoise

can be faster than lightning.

You alone knew that motion

is not different from stillness,

that the void is fullness and the clear sky

the most diffused of clouds.

Thus I understand better your long journey

imprisoned in your bandages and plasters,

Yet it gives me no rest

to know that apart or together we are but one thing.

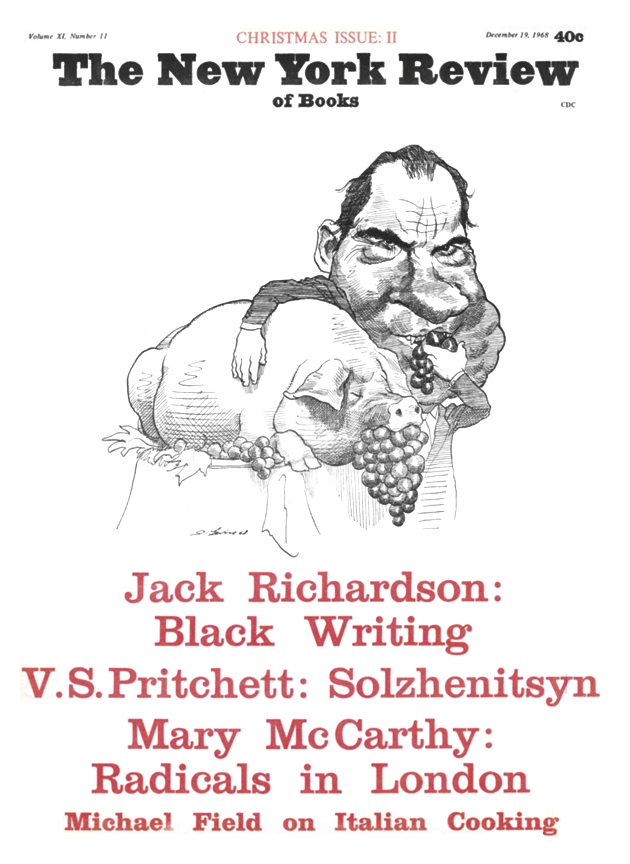

This Issue

December 19, 1968