Mary McCarthy’s proposal in her recent article, “Vietnam: Solutions” (November 9), that we should stop worrying about means of terminating the war and concentrate our full energies on simply getting it brought to an end, is bound to be warmly welcomed by many opponents of the war. This is a weary time. It cannot but be a relief to be told that political effort, as it is demonstrated by the error and insufficiency of the present Administration both in foreign and domestic affairs, is unworthy of the intellectual life as that life is defined by its commitment to morality.

But unfortunately, in clearing the decks for an acceleration of protest unimpeded by practical political concerns, Miss McCarthy leaves one consideration out of account. She fails to mention, except in a contemptuous reference to airlifting “loyal” Vietnamese (the quotation marks are hers) to Taiwan, the problem which for some opponents of the war, myself included, makes the central issue of the Vietnam situation—what happens after America withdraws. Reading Miss McCarthy’s piece one might suppose that “solution” of the war is just a matter of saving face for Johnson by finding a suitable device for negotiation of peace, and of evacuating half a million troops.

These problems Miss McCarthy assigns to the professional politicians and military tacticians—and who would not agree with her? A division of labor which spares intellectuals for thought, and leaves strategies and logistics to those who are trained in them, is eminently sensible. But the fact is that the question of how we should or should not go about negotiation of a peace settlement is not, as Miss McCarthy would have us think, “merely” political. It is a political problem which is also nothing if not a moral problem: it involves the fate of millions of human beings, at least as many as are involved by our presence in Vietnam. If South Vietnam falls to the Communists, who stifle opposition and kill their enemies, is this not of moral concern to intellectuals? Or is the disfavor in which we hold our present practice of democracy a sufficient warrant to regard Communism as the party of peace and freedom? Certainly Miss McCarthy’s refusal to deal with a Communist victory in South Vietnam as any kind of threat to the values she would wish to see multiplied in the world characterizes the preference of American intellectuals for addressing but a single moral culprit, America. But this is a game we play. Most of us know better.

Miss McCarthy cites Kennan, Fulbright, Galbraith, Schlesinger, and Goodwin as instances of the way in which concern with political “solutions” can lead intellectuals to the betrayal of their sole moral duty, protest of the war. In these unhappy examples she would have us recognize an inevitable connection between engagement with the practical aspects of politics and a deteriorated moral sentiment—seemingly, when these men undertook to offer positive suggestions for how this country might proceed to end the war they were in objective effect conspiring with a government they were morally obligated to oppose and only oppose. Surely this carries us rather far in disgust with politics—if moral man is permitted only a negative relation to government, one wonders what keeps all of us who think of ourselves as moral persons from declaring ourselves Anarchists.

One also wonders whether Miss McCarthy, jealous as she is for the special domain of intellectuals, has let herself realize that by limiting the political role of intellectuals wholly to that of dissent she deprives them of an historical privilege they have claimed with some authority—the right to propose and even direct the positive operations of government. It is an honorable roster she now closes to us and it includes—need one remind her—not only liberals content to work within the given structure of the State but also radicals and even revolutionaries who wanted, and sometimes succeeded in achieving, actual governing power.

That old vexed question of the responsibility of intellectuals is, I know, not to be settled in debate with Miss McCarthy. And I am aware that the position she has taken in her article, that the single job of intellectuals and indeed of all decent people is to get us out of Vietnam, the sooner the better and who cares by what means or what follows on our withdrawal, is far too emotionally attractive to yield before a contrary view—namely, that no choice which is careless of its consequences is a moral choice. I think America was and is careless of certain deeply important consequences of going into Vietnam. I hardly think this justifies intellectuals in being similarly careless of the consequences of our getting out.

I too oppose this war and urge our withdrawal from Vietnam, on the wellexplored ground that America cannot militarily win the third world from Communism without the gravest danger of thermonuclear war or, at the least, without conduct inconsistent with and damaging to the democratic principle and the principle of national sovereignty we would hope to protect and extend—the fact that in order to be even as little successful as we have so far been in resisting the Viet Cong America has in effect possessed the sovereign territory of South Vietnam dramatizes the threat to the autonomy of small nations inherent in such ill-considered procedures. But even as I take this stand I confront the grim reality that in withdrawing from Vietnam we consign untold numbers of Southeast Asian opponents of Communism to their death and countless more to the abrogation of the right of protest which we American intellectuals hold so dear. And if, unhappily, I have no answer to the torturing question of what can be done to save these distant lives, I don’t regard this as proof of my moral purity or as an escape from what Miss McCarthy calls the “booby-trap” of “solutions.” I hope that everyone, including intellectuals, will keep on trying to find the answer I lack. For without this effort the moral intransigence for which Miss McCarthy speaks is its own kind of callousness.

Advertisement

Mary McCarthy replies:

Mrs. Trilling has the gift of prophecy. I have not. I do not know what will happen to millions of human beings in Southeast Asia if the Americans pull out. Common sense suggests that the richer and more visible of the “loyal” South Vietnamese will follow their bank accounts to France and Switzerland. Quotation marks are called for since what these people are loyal to has not been determined. Their duly constituted government? Their country? Democratic principle? Their skins? When the Americans use the word, they mean loyal to them: “We can’t let these guys down because they have stuck with us.” Yet the depth of this sense of togetherness can be gauged by what happened to Diem, an outstanding “good Indian” who became a liability.

Let us drop the crocodile concern and talk about realities. It is perfectly true that many thousands of South Vietnamese have been compromised by working for the Americans, as interpreters, language teachers, nurses, drivers, construction workers, cleaning women, cooks, PX-employees, and so on; there are at least 140,000 on the military payroll alone. No outsider can be long in Vietnam without feeling some misgivings as to what may happen to them “afterwards.” Their employers must occasionally ponder this too. One can hope that an AID official, hurriedly packing to leave, will feel some qualms about Minh, who has been driving his car, that a few Marines will think twice about Kim, the girl who works in the canteen. But this is not politics but ordinary ethics; a responsibility felt for people whose lives have touched one’s own and who therefore cannot be expected to vanish like stage scenery when the action shifts elsewhere.

In exceptional cases, something will be done, on a person-to-person basis, assuming Minh and Kim’s willingness: jobs and “sponsorship” will be found in the US; voluntary agencies on the spot will help; neutral Embassies will help. But the majority will be left to face the music; that is the tough luck of being a camp-follower. The departure of an occupying force, the closing-down of an Embassy or a mission means the curt abandonment of the local employees to the mercies of fortune and their compatriots. It happened in France last spring when the US NATO forces were ordered out: what became of the 17,500 “faithful” French employees? It can be argued that that is De Gaulle’s worry.

The work force of South Vietnamese who have “cast in their lot” with the Americans have drifted into politics through the accident or fatality of economics: they were looking for a job. Nobody could seriously place them among the “untold numbers of opponents of Communism,” though in a literal sense that is what they are, and it is they, no doubt, who will have risked the most in the end if the sanguinary scenes imagined by Mrs. Trilling actually are enacted. In that event, one can hope for their sakes that they were secretly working for the Viet Cong (a suspicion that falls on them anyway), in short that they were political after all.

RVN government figures, who have contributed far less to the war effort, in fact who have positively hampered it through graft and other forms of crookedness, are more likely to benefit from a grateful US. The Seventh Fleet and the Air Force would probably stand ready to evacuate the various military men, province chiefs, district chiefs, ministers, and deputies who have been co-operating with us—whether they go to Thailand or are airlifted to Taiwan, the Philippines, Hawaii, or straight to the United States. In other words, the US would look after those who are most able to look after themselves.

Advertisement

And what about the bourgeois intelligentsia, who are relatively few but who really are, for the most part, opponents of Communism, though not necessarily in sympathy with the United States? Some of them, doubtless, will go into exile; others will prefer to stay and make terms with the NLF—signs of this are already evident, not only in the Saigon Assembly but among middle-of-the-road exile groups abroad. There are also the various sects and splinters of sects, Buddhists, Hoa Haos, Cao Daists, who are unlikely to choose exile in large numbers but who can be expected to survive as groups despite their religious commitments, just as Catholics and their priests have in the North.

This leaves the hamlet chiefs, village chiefs, schoolteachers, policemen who have collaborated with the Americans in pacified areas. Many of these people are in the same situation as the “little people” on the American payroll.That is, they have collaborated for non-political reasons, out of a natural wish to go on being schoolteachers, policemen, etc. But, having done so behind the American shield, they live in fear of the Viet Cong. Among the small local bureaucracy there are also convinced opponents of Communism and admirers of American power—of an eager-beaver type found all over the world. Most of these fully expect to be massacred if the Americans go and at the same time, masochistically, they place small reliance on American promises to stay. They see themselves being hacked to pieces, decapitated, along with the non-politicals, who are not quite so sure of their fate.

Indeed, a certainty as to what will happen in the event of a Viet Cong “take-over” is the principal article of faith in the anti-Communist credo. One is against Communism because one knows that Communists massacre whoever is against them. For example, a Jesuit father back from a long residence in Vietnam recently guaranteedme that two million people would be slaughtered if the NLF came to power—he did not say how he had arrived at this figure: his first estimate had been three million but he had knocked a third off as a concession to my disbelief. “You mean you think so, Father.” “No, I know it,” he replied with fervor. Only God knew the future, I reminded him, but he did not seem to agree.

To be fair, the missionary priest was reflecting, quite accurately, middleclass attitudes in Vietnam. The fear of the Viet Cong is a reality in the South. To an outsider, this graphic and detailed certainty appears phobic, the product of an overworked imagination. Eyewitness and secondhand accounts of Viet Cong terror are magnified and projected into the future, as though guerrilla warfare could be expected to intensify in the absence of an armed enemy. In Saigon one evening I talked to a group of twenty or so students who all seemed to be living in a fantasy, fed on atrocity stories, of what would happen to them if the Americans left. A New York Times reporter asked them what they were so afraid of: they were young, they were specialists; a Communist government would need their skills as engineers, teachers, doctors…. They were bewildered by what was plainly a totally new idea; it had not crossed their minds that their training could make them useful to their class enemy. They only thought of being shot, decapitated, etc. All these young people, with one exception, were Northerners, and it had not occurred to them either what this meant in terms of their persistent nightmare: contrary to their preconceptions, they were alive and whole, having been allowed to escape, with their parents, from the jaws of Communism back in 1954.

If it had been revealed to me in a vision that two million people would die as a consequence, I suppose I would not—lightheartedly, as Mrs. Trilling thinks—propose unilateral American withdrawal. The awful fact of having had the vision would lay their deaths squarely at my door. So I would try to hammer out some “solution,” e.g., a new partition of the already partitioned country—a notion already hinted at in J.K. Galbraith’s How to Get Out of Vietnam; mindful of the loyal Vietnamese, he wonders whether Saigon could not be made a free city, on the model, presumably, of Danzig or Trieste, not good precedents when you come to think of it. But what about simple annexation of South Vietnam? This would require a million troops, the expedition of Free World colonists, private investment in factories and power plants, but it would have the advantage of imposing democratic institutions on the South Vietnamese; moreover, the war could be moderated in view of the fact that it would now be taking place on US soil, destroying US property and property-holders; if we concentrated on the task of development, we could seal the frontier, stop bombing North Vietnam—a waste of time—and even interdict napalm.

Short of annexation—a fifty-first state—no solution comes to mind that could give ironelad permanent protection to untold numbers of anti-Communists. All current proposals, starting with Johnson’s at Manila, envision an eventual departure from the scene. If we do not want to extend the boundaries of the US, we are left with no alternative but to extend the war, i.e., continue it along present lines, regularly escalating until all resistance has been eliminated or until our computers tell us that two million and one innocent persons have been killed—at that point the war would no longer be “worth it,” and we could quit with a clear conscience.

Mrs. Trilling says that she opposes the war, but logically, in her own terms, she shouldn’t unless she looks on the slaughter of millions of democrats as the lesser evil. She is also troubled by the threat to the right of protest that an American withdrawal would imply. No doubt it would, yet the lack of a right of protest in South Vietnam at this very minute is not a threat but a reality, as anybody should know from reading the papers. Americans are free to criticize the war in South Vietnam; the South Vietnamese are not. Admittedly, there is more diversity of opinion in the South on this subject than there is, probably, in the North, yet in neither place is there any real freedom of the press or of public debate.

For anybody but a pacifist, the balancing of means against ends in wartime is of course a problem, which can be real or false, depending on whether the end to be obtained is visible and concrete or merely conjectural. If it were known that Ho Chi Minh was sending millions of Catholics or members of ethnic minorities to gas chambers, there would be a real dilemma for intellectuals and non-intellectuals too as to how much force and what kind should be applied to stop him, whether napalm, phosphorus, magnesium and cluster bombs should be used against his population, whether his “sanctuaries” in Cambodia and China should be invaded…. But no one outside the Administration pretends that Ho is Hitler. Mrs. Trilling’s tone suggests that she thinks he is Stalin, yet would she reproach US intellectuals, herself included for having failed to seek an “answer” to save the millions who perished in Stalin’s prisons and slave labor camps? Like the Bertrand Russell of the epoch, did she conscientiously weigh dropping an atom bomb?

There are no “answers” except in retrospect, when the right course to have followed seems magically clear to all. At present nobody can produce a policy for Vietnam that is warranted by its maker to be without defects. Quite aside from Communism, this is a civil war, and civil wars customarily end with a bloody settling of scores, because of the fratricidal passions involved and also for the obvious reason that the majority of the losers have nowhere to escape to; it is their country too. But one can fear this for Vietnam whichever side wins. What safeguards exist for the Viet Cong and its millions of sympathizers and dependents, if a victorious US Army turns their disposal over to the ARVN—its cynical practice up to now? Does that not worry Mrs. Trilling? We know that the ARVN tortures its prisoners and executes civilians suspected of working with the VC. Despite the promises of the Open Arms program the VC too may anticipate a massacre if it definitively lays down its arms. Unlike the Jesuit missionary who “hadn’t seen it in the paper,” the VC must have heard about the recent anti-Communist coup in Indonesia, rejoiced over by American officials (who give our Vietnamese policy credit for it); it was followed by the execution of 500,000 Indonesians, and the unrecorded carnage is reckoned at two million.

YET CIVIL WARS in modern history have not invariably ended with horrible mass reprisals, above all in Communist countries. Take the Hungarian Revolution, which was a mixture of civil war and foreign occupation. To everyone’s surprise very few were killed in the aftermath, and an increase in general liberty followed. Or take the Communist seizure of Poland after the Second World War, when two Polish armies fought each other, one being backed by the Russians. It was not succeeded by a bloody purge; the virtue of Polish Communism, they say, is that no one was executed for political opposition even under Stalinism—Gomulka went to jail. Or take North Vietnam itself, after the French defeat; here too there was an element of civil war, since many Vietnamese fought on the side of and supported the French. Yet under the Geneva Agreement, the North Vietnamese with minor exceptions did not interfere—sometimes even assisted—while 860,000 persons were evacuated (including 600,000 Catholics) by the French Army and the Seventh Fleet. It is true that the emigrants lost their property and that in the agrarian reform of 1955-56 numerous landowners, rich peasants, and others were executed—Bernard Fall quotes an estimate of 50,000. I do not have, for purposes of comparison, statistics on those who died in Diem’s agricultural “experiment”—the Strategic Hamlets program—and if I had, it would not alter the ineluctable fact of 50,000 deaths. It is possible that this could repeat itself in South Vietnam, if collectivization is attempted. Against this is the fact that the mistake was recognized and amends made where still possible (The Rectification of Errors Campaign), and the point about an acknowledged mistake is not to repeat it.

The Hungarian and Polish examples suggest that if opposition is widespread in a Communist state a conciliatory policy is pursued; the turnabout in North Vietnam in 1956, when resistance to the land reform purges led to open rebellion, further illustrates the point. If, on the other hand, opposition is confined to a minority, that minority is dealt with ruthlessly. Let us assume this principle applies: Mrs. Trilling should be reassured if she is confident that opponents of Communism in Southeast Asia can be counted in the millions. But if she over-estimates their numbers, then indeed she has grounds for alarm. On the other hand, if they are relatively few—say, in the hundreds of thousands—evacuation ought not to present insuperable difficulties. As for their readjustment elsewhere, one cannot be sanguine. Nevertheless, here too there are precedents: the United States has been able, for instance, to absorb 300,000 escapees from Castro’s Cuba—a statistic not usually remembered in this kind of discussion.

Of course this little principle, whatever comfort it may offer, is not a “law.” Nor is evacuation of a whole minority of oppositionists imaginable except in a blueprint. Some would miss the boat. Let us suppose that whatever happens, a thousand will be left behind, to be tried and executed by People’s Tribunals or cut to ribbons in their hamlets. Or a hundred. Or only one. It is the same. Mrs. Trilling would have his death on her conscience. She condemned him to die by her opposition to the war. She failed him. We all failed him. We ought to have thought harder—that is Mrs. Trilling’s attitude. But we condemn thousands of people to death every day by not intervening when we could—read the Oxfam ads. Or the appeals in the morning mail; yesterday I condemned someone to die of muscular dystrophy. I judged some other cause “more important.” Not to mention my own comforts and pleasure. I am calloused. Everyone today who is well off is calloused, some more, some less. This has always been the case, but modern means of communication have made it impossible not to know what one is not doing; charitable organizations are in business to tell us all about it. When Mrs. Trilling reproaches me as an intellectual for my lack of moral concern, she makes me think of the Polish proverb about the wolf who eats the lamb while choking with sobs and the wolf who just eats the lamb.

What Mrs. Trilling wants is a prize-winning recipe for stopping the war and stopping Communism at the same time; I cannot give it to her. Nor frankly do I think it admirable to try to stop Communism even by peaceful subversion. The alternatives to Communism offered by the Western countries are all ugly in their own ways and getting uglier. What I would hope for politically is an internal evolution in the Communist states toward greater freedom and plurality of choice. They have a better base, in my opinion, than we have to start from in dealing with such modern problems as automation, which in a socialist state could be simply a boon.

Certainly, town planning, city planning, conservation of natural and scenic resources are more in the spirit of socialism, even a despotic socialism, than in that of free enterprise. Today, in capitalist countries, the only protection against the middle-aged spread of industrial society lies in such “socialistic” agencies as Belle Arti and the Beaux-Arts, concerned with saving the countryside from the predations of speculators and competitive “developers,” like real-estate developers. It seems possible, too, that Communism will be more able to decentralize industries through the exercise, paradoxically, of central control than the Welfare State has been. And variety of manufactures, encouragement of regional craft, ought to be easier for Communist planners whose enterprises are not obliged by the law of the market to show a profit or perish; there is no reason that “useless” and “wasteful” articles should be made only for the rich. In any case, external pressure is not going to liberalize Communist regimes; that seems to be fairly clear. It can only overthrow them or act to prevent them from taking power, with consequences that liberals, in view of Greece, Spain, Indonesia, might not be eager to “buy”.

I should like to see what would happen if the pressure were taken off. What would Vietnam be like today if the United States had pressed for elections in ’56 and the country had been unified by popular vote—which hindsight finally concedes might have been the best plan? Greatly daring, I should say that the best plan right now, eleven years later, might be to give the NLF a chance to enact its program. This calls for a National Assembly freely elected on the basis of universal suffrage, a coalition of classes for the reconstruction of the country, gradual and peaceful unification with the North, an independent and neutralist foreign policy. It guarantees the rights of private property and political, religious, and economic freedom. Whether this program, evidently designed to allay the alarms of the middle-class Vietnamese, is to be taken at face value, that is, whether the Front really means it, is something no one outside the Front’s councils can know for certain. One can hope that it is so and fear that it is not. And even if the program, with its proffer of amnesty (and threat of punishment for those who persist in collaborating with the invader), is offered in good faith as a serious design for the future of the South, events may overtake it, e.g., a right-wing rebellion, disastrous floods, a famine…. Yet for the Vietnamese this is the only “solution” at present available that gives any hope at all. Plans such as that of Philippe Devillers, proposing internationally supervised free elections to take place first in the Saigon-controlled zones (while the Americans retire to coastal enclaves) followed by general free elections in the whole of South Vietnam (after which the Americans would leave), amount in fact to showing a way in which the NLF program might be arrived at step by step with the cooperation of Saigon and of all interested parties.

Mrs. Trilling, doubtless, would think anybody a sucker who let himself be taken in by the promises of Communists, yet the promises of Communists sometimes correspond with their assessment of political realities: when Ho kept his word and let the emigrants go, he got rid of 860,000 opponents in one pacific stroke. Moreover, he had 860,000 fewer mouths to feed and a great deal of free land to distribute. The NLF would have the same motive to allow if not strongly to encourage the departure of oppositionists. Besides, if it is going to rebuild the country, the NLF will need cooperation from a variety of political and social groups, as well as credits, which might even come from the West, from General de Gaulle, for instance, from Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Canada.

The power of intellectuals, sadly limited, is to persuade, not to provide against all contingencies. They are not God, though Mrs. Trilling seems to feel that they have somehow replaced Him in taking on responsibility for every human event. This is a weird kind of hubris. In fact intellectuals and artists, as is well known, are not especially gifted for practical politics. Far from being statesmen with ubiquitous intelligence, they are usually not qualified to be mayor of a middle-sized city. What we can do, perhaps better than the next man, is smell a rat. That is what has occurred with the war in Vietnam, and our problem is to make others smell it too. At the risk of being a nuisance. I reject Mrs. Trilling’s call to order. The imminent danger for America is not of being “taken in” by Communism (which is what she is really accusing me of—that I have forgotten the old lessons, gone soft), but of being taken in by itself. If I can interfere with that process, I will. And if as a result of my ill-considered actions, world Communism comes to power, it will be too late then, I shall be told, to be sorry. Never mind. Some sort of life will continue, as Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, Sinyavski, Daniel have discovered, and I would rather be on their letterhead, if they would allow me, than on that of the American Committee for Cultural Freedom, which in its days of glory, as Mrs. Trilling will recall, was eager to exercise its right of protest on such initiatives as the issue of a US visa to Graham Greene and was actually divided within its ranks on the question of whether Senator Joseph McCarthy was a friend or enemy of domestic liberty.

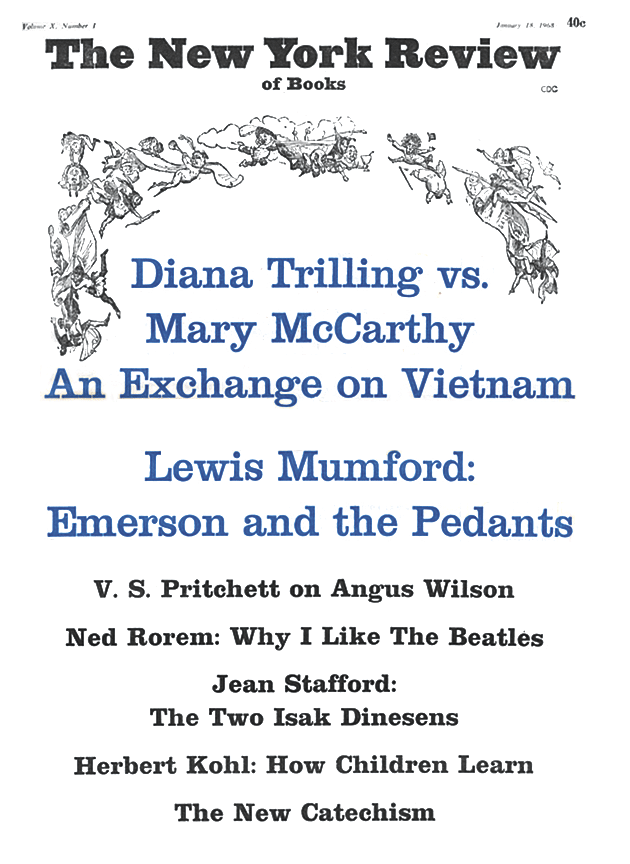

This Issue

January 18, 1968