In response to:

The Little Foxes Revived from the December 21, 1967 issue

To the Editors:

Miss Hardwick was recently quoted as saying: “I think of myself as a person whose interest in the dramatic is primarily literary.” Perhaps this is why so many theater people find her reviews confusing. It is true that a good play on the stage must also be a good play on the page, but a qualified theater critic should understand what must happen in the transference from page to stage.

I, myself, started as a musician, and I know that an interesting critic of music must not only be able to read a score but to understand that metamorphosis from reading to performing. Plain, simple, old-fashioned knowledge should be the first requirement of any criticism. Perhaps it is this lack of knowledge that caused Miss Hardwick to write a review of The Little Foxes that is puzzling to so many of us. Moreover, I find the review highly subjective in tone, which for me has undermined its validity.

Felicia Montealegre

New York City

Elizabeth Hardwick replies:

If a critic writes a favorable review he is brilliant and perceptive; if he writes a negative one he “lacks deep knowledge,” is “puzzling,” and “confusing” and “subjective.” (This is ordinarily summed up in the phrase, “knows nothing about the theater.”) It was ever thus…. Richard Poirier objects to my effort to look closely at Lillian Hellman’s plays, to try to see what they are about, to try to place them in their period and in our own dramatic tradition. I have read and re-read this work and know it intimately; I have seen nine of the original productions of her plays. I saw Patricia Collinge play Birdie and I have seen Margaret Leighton. I also have a picture of Miss Hellman’s ideas of the character from reading and seeing Another Part of the Forest. Birdie is always played sympathetically, to put it mildly. In the refinements of her feelings, her love of music and memory (in Another Part of the Forest the Hubbards are very mean about music, as well as other things) she seems to me to stand for the sentimental, plantation idea of Culture. Perhaps when my correspondent, Felicia Montealegre, takes over the role on Broadway, as she is now doing, she can bring to it some of the qualities Poirier finds in the character. I believe Horace is a dull puppet of righteousness and that this, rather than his convenient heart-attack, is a defect even in the melodramatic interest of the play. I also think Watch on the Rhine and the strike play, Days to Come, combine in a very peculiar fashion the traditions of Broadway drawing room comedy and Broadway realism…. That Lillian Hellman’s plays are written as she “wanted it” I could hardly question. Yet I also do not question my right as a critic to study her work, see it on the stage, analyze it and judge it according to my own lights.

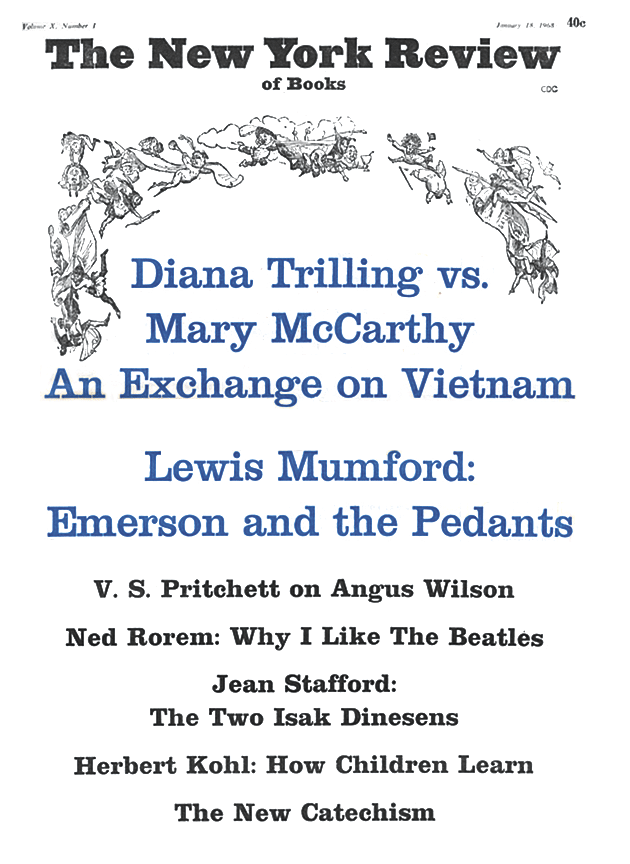

This Issue

January 18, 1968