The sublime sphinx show that has been Andy Warhol’s career: the films and the paintings, the Brillo boxes and the balloons, the Factory and its repertory company of underprivileged agents provocateurs—isn’t that, finally, what we expect a certain ineptness christened with a certain audacity would amount to? Robert Indiana munching an apple; Mario Montez as Harlow in Harlot (in drag) munching (or mouthing) a banana; Nico moaning and mumbling or brushing her hair; Roger Trudeau and Edie Sedgwick, god and goddess of Formica Heights, the super-stars, that is, of Kitchen, sneezing at one another—memorable moments from the story of Andy Warhol, museum pieces or conversation pieces, arresting and inane.

The things I want to show are mechanical. Machines have less problems. I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?…

Warhol is piquant, I suppose (particularly in the one or two public statements he has made), but then, I think, like all novelty, he has to be. A literalist not of the imagination, but of the “shockingly” banal, the ineffably “real,” “The Exploding Plastic Inevitable”—in him, indifference pushes itself to such a Hegelian pitch as to appear to be insolence. To literary people, no doubt, Warhol is an artist seemingly denuded of any redeeming value whatever, a magician without magic, though not an act. A Warhol pumpkin, unlike that of the lady with the wand, doesn’t transform itself into a stagecoach; the pumpkin becomes…a Pumpkin. And yet, with wit, with luck, with appalling foresight, with the help of Rivers and Rauschenberg and Jaspar Johns, perhaps even a Polish jig, it was, let us remember, Andy Warhol who turned to the trash of the times, to the ad, the debased documentary—and what is more naturalistic than Blow Job, more commercial that Martinson’s Coffee?—and made “art” of the unredeemable. Or as they say, anti-art, Pop art, cinéma verité.

Warhol’s literal-mindedness is splashed over everything he has ever done, from the stereotypical silkscreen sequences of Marilyn and Liz, to the tape-recorded “novel” he chooses to call a, a total environment of typos and sputterings, hellish hymns from Amphetamine Heaven, the vox populi of the Velvet Underground: “Please, basta, with the tape Drella, for a little while. Shut it off, let’s relax ’cause we’ll go crazy.” The literal-mindedness is so tyrannical it seems obscure, so blank it suggests the revelatory. In the old days, after the galling pace of a Warhol film, the baffling redundancy of a Warhol painting, one always awaited something else, a mystery message d’outre-tombe. That the message, as it turned out, was the simplest sort; that it resembles, in whatever form, shape, or dialectical seasoning, nothing so much as Miss Ethel Barrymore at her sweetest: “That’s all there is; there isn’t any more”—well, these are facts all of us now know. But alas the message never ends…

Warhol is an inevitable “creation,” an inevitable “genius,” it seems to me, a haute vulgarisation of sorts. Born in the late Twenties, sociologically he’s the prodigy of the Sunday supplement, the dividend of the Look and Life color spreads on Matisse and Picasso, the Khans and Rita Hayworth, the desideratum of all those cocktail parties of the Forties and the Fifties, of all those Auntie Mames of whatever class or sex who enjoyed not culture but talking about culture, not ideas, not emotions, but the “full story” in three pages, people who have always needed certain phrases, certain situations and events to be “in,” “with it.” “My dear,” a lady remarked recently, unwittingly making the author of “The Decay of Lying” turn over in his grave, “I never looked at a Campbell’s soup can until Andy Warhol showed it to me.”

It is often said that so much that is decadent and lewd meets in Warhol and of course that’s so, and not so. Warhol is really like a depraved Parson Weems dreaming of Andy Hardy. He’s so American, as American as Consumer Reports and Flash Gordon serials and church socials, and yet so pointedly strange. So bland, yet weathered. As accommodating as a teacher’s pet, but how prodigiously knowing, what a fugleman. The famous cheveux de lin, the cuddly ugly Actors Studio pauses (“uh…uh…huh?”), the silver screen shades, the puckish chin and the pudgy nose, the cyclist’s jacket and the cyclist’s boots, his finger on his lips, amazingly cool, yet amazingly pure, “faceless” almost. The much discussed element of debauchery in his work (at least in the films and the current fiction; more or less sprightly in the early efforts, like last year’s garbage in a), has always had, whatever its varying descents or disorders, the aura of one of those high school proms of a generation ago, the senior class band mimicking Glenn Miller and “The American Patrol,” while a few of the boys from the better families shoot up in the john. The juxtaposition of these things, of the mindlessly banal and the haphazardly corrupt, or of the totally outrageous and the totally bloodless (“I feel that whatever I want to do and do machine-like is what I want to do”), is indeed what has come to be known as the Warhol style, the one palpable display of an idiosyncratic spirit or sophistication, but it is, I think, a sophistication largely through default.

Advertisement

Unlike John Cage, say, the student of boredom and cracker-barrel Zen (“Form is what interests everyone,” says Cage, “and fortunately it is wherever you are and there is no place where it is not”), Warhol, neither intuitively nor programmatically, ever suggests that he has the slightest understanding of what the sophistication means or “is.” Those faux-naif reconstructions of “evil” or “unorthodox sex,” of “the perils of drugs” or “sado-masochism,” to be found, for instance, in Couch or Bike Boy or The Chelsea Girls, are, at one level, sermonettes sardonically demonstrating the absurdity of all sermonizing, at another level, impudent panderings to the eternal bourgeois hankering after the obscene and the forbidden, bu at the deepest, the true Warholian level, simply and gratuitously tautological fun and games, spastic ideas set in spastic motion. A twenty-four-hour film—and who hasn’t wanted to do that since Gone With the Wind, or to call it when assembled Four Stars? A real shocker: the face and the chest of a young man, the suggestion of some sort of shadowy hanky-panky happening below, and nothing else filling the screen for thirty minutes—and you call it Blow Job…

Warhol has his following (it’s really a myth that most artists or critics do not approve of him—some do, unreservedly), and aesthetically, no doubt, he’s “interesting.” One may, as others have, call the absolute exposure of the Empire State Building in Empire an experiment in duration, the monosyllabic spasms of a starlet in Screen Test an experiment in disorientation; one may associate Warhol with the mystique of technology, with the objectification of the random and the everyday; or sense in his work the august presence of Davis and Magritte, the ready-mades of Duchamp, the theories of Ponge and Dubuffet. Nowadays all combinations are possible, like the headlines in the newspaper. Still, the breathtaking assertions of fifty years ago—“A roaring car that appears to be driving under shrapnel,” declared Marinetti, “is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace”—can seem a shade farcical later, especially when reduced to the celebration of the supermarket. Andy Warhol is mod, but he’s also archaic. “I like Edison. Oh, do I like Edison!”—and you may be sure that the creator of Kiss and The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys isn’t kidding.

What is a about? If one were to take a seriously, one would have to say it is about the degradation of sex, the degradation of feeling, the degradation of values, and the super-degradation of language; that in its arrant pages can be heard the death knell of American literature, at least from The Scarlet Letter onward. Actually, it’s about people who talk about Les Crane and Merv Griffin. These people are called The Duchess and Rotten Rita, The Sugar Plum Fairy and Irving du Ball, as well as other Runyonesque appellations. Throughout a they chat on the phone and they chat in the cab, they chat in the restaurant and order a Western Russian or a Russian Western, they chat especially when stoned. a is a bacchanalian coffee-klatch. Here is what Judy Garland said to Nureyev in the elevator: “You filthy Communist spy, you…it’s so beautiful.” These people are witty and they are grand; like royalty they cannot spell and they are barely educated (“Samurami… It’s incestral… I don’t know who wrote the original. I think uh Cóle Porter.”). They do terrible things and make awful remarks (“There’s no question about it, he must be poisoned this week—arsenic.” “Oh Drella, may I wear your sun-glasses, now?”). They appear for a full day and a full night. The Duchess slips into a hospital and slips out of the hospital; she steals a blood-pressure machine, or doesn’t steal it. Andy Warhol also appears; he appears as Drella (it is not clear why, but le roi s’amuse). The wit is the wit of a meeting of film buffs for brunch at Riker’s in the Village: “the original of Comrade X was called Madame X!” In the Thirties, Mae West referred to Shirley Temple as “that fifty-year-old midget.” So Ondine refers to Gerard Malanga as “Gerald Malingerer,” to Mel Torme as “Mel Torment.”

Advertisement

Ondine, the Pope Ondine of The Chelsea Girls, is the hero of these parts, too. Ondine is a little didactic, a little operatic, and rather cloacal, an East Village prima donna, both anal and oral, a hoarder of gossip and finery and orgies and drugs (“AAA-aaaoww—the Marijuana March, the Heroin Pop, an the uhuhuhAmphetaime… What? Ascot I suppose”), a tithering neurasthenic, stuffed with all the vagaries, all the scatological puns and proclivities of a banker’s widow, a post-Freudian Volpone (is Drella his Mosca? is Ondine really Hester Prynne?), surrounded by slack-backed clowns. Not surprisingly, the most interesting thing about Ondine is that he has a “thing” for ass. The buttocks of Steven or Lou, however, are coveted not for ramming or rimming or aesthetic contemplation, but (if I understood Ondine’s aria) for more elegant elaborations. Ondine is filthy, but he is funny. Here is Ondine remembering the days when he did to another what he perhaps subsequently wished to have done to himself.

He said, “Please try it.” I said, “Well, I’ll try, but I’ll feel silly.” And I couldn’t do it. I could not do it. I said to him. “I know what we’ll do, let’s get a can of baked beans, open it up, you take the pork out and you put them up one by one, would you try, and then I’ll squat over you, and I will shit them out.” And I did. And he was in seventh heaven…

These people, really, are closer to ghouls in the true sense (or the comic sense) than anything that American culture has created since Karloff and Lugosi and Zita Yohann. They are spook hour hysterics smothered in sedatives, non-stop gabbers on a Transylvanian talk show. If Warhol were a genius, they would be devastating. As it is, the characters of a, like many of the other characters of Warhol films, suggest the final touch, or the final solution—they represent the bizarre new class, untermenschen prefigurations of the technological millennium, as insulated from the past, from pleasure and pain, from humanism and the heroic tradition, as were pygmies and dwarfs from knights in armor. Sterile and insentient and instantly dated, void and verbose, yet they instantly proliferate themselves and each other.

Certainly a is not the glory hole of hell the popular press takes it to be: no one in a bemoans the “breakdown of relationships,” “the impossibility of communication,” “the corruption of childhood”; or behaves in any way that would suggest he indeed pads the terrible abyss. Malcolm, in Edward Albee’s adaptation—to take a more or less typical example of the literature of the insulted and injured—is done like Alice in Wonderland. Malcolm, the innocent teen-ager and underachiever, being Alice, with all the desperate adults performing like updated Lewis Carroll grotesques. Albee’s Malcolm is eminently sentimental, even instructive: the grotesques, like the audience, are expected to pass through the looking glass and see how wicked they are, having caused Malcolm’s death. They refused to take the boy seriously, they treated him as a thing (cf. Sartre, not Ondine). There’s a pop-existential moral to Malcolm; Warhol is art without morals or manners and completely without sentiment.

In one of his essays, Jean Dubuffet speaks of “the rehabilitation of scorned values,” of the necessity of sweeping away “everything we have been taught to consider—without question—as grace and beauty,” of substituting “another and vaster beauty, touching all objects and beings, not excluding the most despised…the most destitute.” Dubuffet spoke eloquently, and with ardor, of his ideal, his l’art brut, and implemented the ideal in his painting. And yet, though stood on its head, the “ideal,” I think, is to be found in the work of Andy Warhol, too. For what, after the bubbles have burst and the stumbling blocks been crossed, do we discover at the center of Warhol’s world if not the supernumerary—from the collection of secondary objects, the deadpan sanctification of the billboard and the detergent, the “despised” institutions of commerce and advertising, to the array of secondary characters, the “destitute” embodiments of sub-marginal life-styles, the castaways, not just of life, but of the entertainment world as well. It is not, as is customary with camp, a leading man or a leading lady that a Warhol character wishes to travesty; rather, like Dubuffet, it is the fill-ins, the “scorned” ones, those who are already campy, that he wishes to appropriate or impersonate. Ondine, the Duchess, Irving du Ball—behind the “naturalistic” pose of the swish and the bull-dike or the junkie and the hood, what we really glimpse and hear are the mincing butler and the horsey maid, the bleached floozie and the runty pimp, the stock gadabouts of situation comedy, the skulking ones of melodrama, all at long last stepping up to the footlights, “flying high” in a series of patchy, aggressively absentminded transformations. In My Hustler (along with the “Hanoi Hannah” and “Pope Ondine” sketches from The Chelsea Girls, the best of Warhol’s films; in its way tough, elegant, and nasty), it is a literary figure who is subverted—the kind of beau ideal of a Wilde or Cocteau romance, subverted or traduced pretty much in the mode of a gay bar joke, especially the early scenes of Mr. America creaming himself on the beach at Fire Island and reading a comic book, while a fat and horny roué mockingly recites Dante, in competition and/or counterpoint with another hustler, a fading one, and a debutante, a “fag hag.”

The effrontery of Warhol’s strategy, the stray snatches of deliciously dopey dialogue (often the contribution of Ronald Tavel, but, in the punch-lines, at least, much more the voices of Lenny Bruce and Noel Coward, Mae West and William Burroughs, an improbable mix in an old fashioned blender), coupled with an atmospheric verisimilitude which can, here and there, make so-called underground classics, such as Balm in Gilead and City of Night, seem mawkish and mundane—all these elements, at any rate, allow for Warhol’s momentary successes. But successes of that sort are scarey. Ultimately a Warhol work reminds one of those plights in science fiction where an interplanetary germ or some amorphous plant life invades human consciousness and everything sloppy and slight takes over. Even the perverse, the sexually extravagant becomes pinched—or predictable, like canned laughter. Compare the tittletattle naughtiness of Ondine with Firbank’s Cardinal Pirelli chasing a choir boy around the Cathedral of Clemenza, and then dropping dead in front of a painting depicting the martyrdom of Christ; or remember Proust’s Charlus or Genet’s Divine, and you see clearly that a cultural gutter has been reached.

The auto-destructive sculpture of Tinguely, the defecation iconography of Robert Whitman or Sam Goodman, Paradise Now and its coup d’état: a “liberated” water ballet (“Are we gonna talk about Bolivia, or are you here just to look at our big dicks?”)… What has been happening in Warhol has been happening, to lesser or greater degrees, throughout the Sixties. A power vacuum exists in culture today, frequently filled with self-congratulatory innovations, demagogic somersaults, ponderous theorizing—the evangelical “new sensibility,”* the bridging of the gulf between art and life. It’s an historical problem. “Why must I think,” asks Mann’s Leverkuhn in Doctor Faustus, “that all the methods and conventions of art today are good for parody only?” Leverkuhn approaches the question with anguish. The most Warhol (and how many others?) seems able to do is snigger.

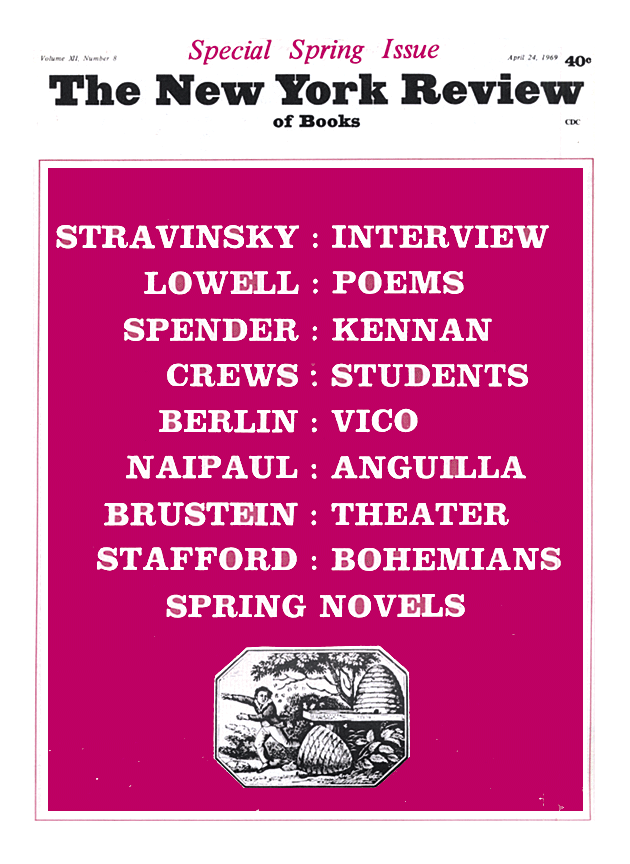

This Issue

April 24, 1969

-

*

The phrase, incidentally, is Ortega’s, not Susan Sontag’s. Ironically enough, in “The Dehumanization of Art,” the phrase refers to a state markedly different from that which the “new sensibility” currently signifies. “We shall yet see,” Ortega writes, “that all new art (like new science, new politics, new life, in sum) abhors nothing so much as blurred borderlines. To insist on neat distinctions is a symptom of mental honesty. Life is one thing, art is another let us keep the two apart.” Ortega, of course, is discussing modernism; we are post-modern. ↩