The true novelist may be obliged to outrage his readers; the shrewd novelist will settle instead for being “outrageous.” The true satirist will regret the fact that satire is a sort of glass wherein beholders do generally discover everybody’s face but their own; the shrewd satirist will welcome such complacencies, glad that he can have all the prestige of being hard-hitting with no risk of bruising his knuckles. Caricature as indiscriminate and imprecise as that in Montherlant’s The Girls exists to exonerate and gratify its purported victims, since nobody but a masochist need ever concede that Montherlant scores. Instead of a palpable hit, he offers a merciless drubbing—one which turns out to be that of the masseur. Not an anguished Timon, cynically profound and not merely “profoundly cynical,” but an angostura Jaques, such as any court circle will find refreshingly tart.

The Girls (1936-9) is a tetralogy about a novelist, Costals, and his four women: Solange Dandillot, a pretty nothing who nearly wins Costals to marriage; Andrée Hacquebaut, a suffering intellectual; Costals’s religious correspondent, Thérèse Pantevin; and Rhadidja, an Arab girl in Morocco. Costals eludes them all, causing them some suffering and himself an odd twinge, and all the while elaborating—with not much more variety than that of self-contradiction—his worldly-wise views on women and on the disastrousness of marriage.

“All’s well that ends well,” ends the Epilogue, happy that Costals flew free. Behind Montherlant’s two favorite tones, the manly rasp and the silky scorn, there can usually be heard a reassuring murmur: Not to worry. At the concert: “Pig-faced men with eye-glasses pretended that the slightest whisper in the hall spoiled their ecstasy.” As caricature that is gross, not Grosz. George Grosz had to capture such men in the fine net of his draughtmanship; Montherlant simply brands them “pig-faced,” a branding to which they mildly submit because they are the porkers of blustering fiction rather than the boars of life. At the cinema: “five hundred half-wits licked up this pus with ecstasy.” What makes so undifferentiated an accusation impinge? And why isn’t Montherlant’s contempt as morally vacant as his half-wits’ ecstasy? “Beneath him, on the viscous pavement, flowed the race of men, of sub-men and of women, a vast stream of liquid manure…” But beneath this verbal violence (itself somewhat flaccid) there can be heard the small voice, Not to worry: readers have paid for a seat up here with our hero, not down there on the pavement.

Jaques used his folly like a stalking-horse, and under the presentation of that he shot his wit. Montherlant finds it more fun, and even less risky, to shoot the stalking-horses. In the waiting room, a doctor “passes by with his cigarette in the air—not that he is a smoker (he is nothing of the sort), but because smoking being forbidden here, it is a sign of his power.” But what is the level of this as insight or indictment? What are we being offered but a willful “sign” of Montherlant’s “power”? What is a grown man like Montherlant doing playing with a toy such as this prefabricated doctor, trundled into the room for a moment so that it can be cuffed? Even the attacks on complacency are themselves complacent, since they locate the vice in some non-person, a doll to be belabored:

Costals imagined all these men in uniform, and then he loved them, whereas in their civilian clothes he had a tendency, typically ruling class, to regard them as malingerers. “That fat one, for instance…. Is it possible,” our professional psychologist asks himself, “to be ill and fat at the same time? And this one here with his shifty look, there’s obviously nothing wrong with him, absolutely nothing.” Whereupon the man with the shifty look turns round and shows the professional psychologist an empty coat-sleeve.

But the person who is asking himself all this is an empty coat. As with the worst, the most contrived, of Hardy’s “Satires of Circumstance,” the crucial question is: What sort of victory is being achieved here, and at whose expense? The man with the shifty look loses his arm not because of the war but because Montherlant needs to hire a one-armed man, and “our professional psychologist” functions as a whipping-boy. “Use every man after his desert, and who should ‘scape whipping?” We should all escape, provided our professional novelists would provide enough whipping-boys.

Hence the vast number of minor characters who put in a brief appearance so that Montherlant can be mordant about them. Such as the family from Oran, who “vied with one another as to whose nails should be most deeply in mourning—perhaps mourning their lost illusions about French colonization in Oran.” So sharp-eyed an observer, spotting the dirt under imagined nails and witticizing about it. But the witticism—like too many in The Girls—suggests that French adult wit too much resembles English schoolboy wit.

Advertisement

“Their pallid, and, my God, so unprepossessing Parisian faces”: can a concept like the unprepossessing take us very far in an understanding of human beings? “But still, a man after the age of eighteen was not exactly appetizing.” It is all ironic, self-possessed, laconic—and all to what end? As Peter Quennell concedes in his Introduction, Costals is “a personification of the writers’s beliefs and prejudices rather than an individual human being.” And Montherlant has invested too much of himself in Costals to allow the risk of giving him a physical presence, since the vulnerabilities of the physical had better be reserved for those whom Montherlant or Costals wish to wound. The disliked characters have bodies, absurd, ridiculous, unprepossessing ones. Like the head-clerk:

His mouth was repulsive, warped at the edges, slimy and wet with kissings and suckings and lickings—a mouth doomed to cancer in three years; with a cigarette butt dangling from it. His flesh bulged over his collar, which was of celluloid, cracked at the corners. His chin had such dimples, my dear!

But then Costals has the moral fineness to be able to afford non-celluloid collars, and though he too does a certain amount of kissing and licking, he had the good sense to hire Montherlant as a Public Relations Officer, at hand to protect him with jocosity and waggish finger-wagging about his “over-indulgence in sporting or cytherean exertions.”

The scare that Costals may have caught leprosy from his Arab girl Rhadidja (not to worry) is a belated pretense by Montherlant that he has provided a body for this free spirit with whom he is narcissistically in love. What do you mean, he’s just a sheaf of cynicisms, not a person—he damn nearly caught leprosy, didn’t he?

Montherlant exhibits toward the physico-moral a malevolence such as is a permanent temptation to the accusatory novelist. What can be easier, and what more futile, than casually to endow a character with an unpleasing physique and then score off him? What could be more difficult than to insist that there may indeed be a relationship between the physical and the moral in a person’s face or physique, and yet that this relationship may be subtly unamenable to any crude extrapolation or accusation? In Montherlant, the man with the moustache asks for it:

Dr. Lobel was a man of about fifty, with the hair of a photographer and the moustache of a drawing-room actor; that is to say rather long hair—though not long enough for a bad painter’s—and a few close-cropped hairs on the upper lip, like one of those actor-counts whose whole life would be ruined if he did not have the sensation of being hairless, but who keeps a few hairs to appease the countess.

That is airy bullying, not the less objectionable because Dr. Lobel—like most of Motherlant’s characters—is a flimsy figment. For a very different kind of concern with something similar in life, there is a letter by D. H. Lawrence:

Mr. Jones has shaved off his moustache, and I don’t like him. He’s got a small, thin mouth, like a slit in a tight skin. It’s quite strange. It shows up a part of his character that I detest: the mean and prudent and nervous. I feel that I really don’t like him, and I rather liked him before.

What is fine there is Lawrence’s uncoercive perplexity, his sense that he has become aware of something difficult but real, a relationship between the physical and the moral which defies any grossly moralizing confidence. For Montherlant, no moralizing confidence can be too gross.

Gross, but neat, as in all the epigrams. Many of them did indeed move me to anger, but not in the way intended, since the anger is not at their “catastrophic honesty” but at their passing for honest; not at their profound freedom from convention, but at their rakish conventionality. Vapid tough-mindedness about women is quite as conventional as Petrarchan courtliness. “One of the horrors of war, to which attention is never sufficiently drawn, is that women are spared.” Not true, not witty, and not capable of focusing anything but puerile “disillusionment.”

But why think that Costals is endorsed by Montherlant? Is it not an elementary critical mistake to equate a character with his creator? Did not Montherlant offer a Foreword? (Or was it that he felt obliged to offer one?)

The author would like to point out that in Costals he has deliberately painted a character whom he intended to be disquieting and even, at times, odious; and that this character’s words and actions cannot in fairness be attributed to its creator.

But an author is in no position to clear himself of collusion, and the ways in which Montherlant dissociates himself from Costals are about as convincing morally as those in Jacobean melodrama. If The Girls is by now a “classic,” it ought to be so only in the sense of being a classic case of fiction in which an author substitutes evasion and vacillation, a corrupted irony, for disinterested sincerity and courage.

Advertisement

Much has been made of Montherlant’s “honesty”—his views about women, says John Cruickshank, “boldly express what most men feel on occasions but normally try to conceal—from themselves as well as from others.” But “Montherlant’s quite exceptional honesty” reminds me of another notoriously honest figure. When Montherlant observes that, at the concert, “the genii of music, or rather the bank-clerks, played very softly: it might have been a clyster-pipe band,” behind him there hovers honest Iago: “Yet again, your fingers to your lips? Would they were clyster-pipes for your sake.” For Montherlant’s vaunted honesties about women are nothing but the juiceless conventionalities of Iago’s cynicism. And Iago was more terse: “You are pictures out of door: wild-cats in your kitchens: saints in your injuries: devils being offended: players in your housewifery, and housewives in your beds.” Montherlant has chosen to suckle fools (they being easier to raise laughs at) and to chronicle small beer. He admits it himself—but then he admits everything, always stalling and forestalling: “The author pauses… Describing mediocrities always gets you down in the end.”

Something to Answer For: the title of P. H. Newby’s novel implies a notion of responsibility at which both Montherlant and his Costals might raise a lofty eyebrow. But the success of Mr. Newby’s fiction is precisely in its manifestation, both in itself and in its characters, that responsibility need not be priggishness—that, indeed, priggishness is a form of evasion, like breast-beating. The most attractive thing about Leah Strauss was that “she honestly didn’t consider that life was all her fault”—or rather, that she combined this with honestly considering that some things in life were her fault.

The public something that has to be answered for is the invasion of Suez in 1956. In Egypt at the time is Townrow, a disreputably self-indulgent figure who has arrived at the request of an old friend, Mrs. Khoury. Her husband has been found dead in the street—she imagines murder. Once Nasser has taken over the Canal, Townrow finds himself suspected of being either one of the advance party for a British invasion or a spy—but then he finds ludicrous this assumption that “the British were nasty enough to start a war.”

Nastiness at government level, at least within the British government, is unimaginable to Townrow. Personal nastiness he has some conception of, being himself not without a smack of it. But his misgivings are not self-flattering, and although he permits himself some Costals-type cant (cynical cant, of course), there is no disguising the threadbare nature of it all: “The main thing was to be honest about yourself, be yourself, accept yourself as a crook, if that’s what you were, enjoy yourself.” For at least Townrow is naive, and in the end that is what saves him. His offensiveness—“Speaking for himself he’d always been pro-Jewish, especially pro–Jewish women…”—will prove to be open to experience, whereas the offensiveness of Montherlant’s Costals, in the very same area, is shallow but impenetrable, a high veneer that glitters in his letter to Rachel Guigui: “I love intelligence. And that is why, whatever my team of the moment, I must always have a Jewish mistress in the batch. She helps me to put up with the others.”

By contrast, Mr. Newby’s novel has the right modesty, so it will never pull off the kind of bluff represented by The Girls. I can’t see Something to Answer For being reissued thirty years after publication. What Mr. Newby offers is not without amibition—the invasion of Suez was certainly something to answer for—but it is an ambition continually sensitive to the feasible and the faithful. Political events within this setting are clumsy and domestic, not grand designs or juggernauts. People get hurt, and then they look hurt, not picturesque novel-fodder. “Townrow pointed his mind at the international situation”; like many of us, Townrow doesn’t so much think about the international situation as point his mind at it. Better than nothing, but not enough.

“It was still dark when Townrow was awakened from heavy sleep by banging on the door of the flat. He opened the door and found he had soldiers.” This catches, with truthful dryness, the secure British assumption that a knock means you have visitors; catches it, rotates it disconcertingly, but doesn’t belittle the political security which fosters such complacency. “You live very smug,” says a Greek to Townrow about the British. In insisting that the British must do better than smugness, this witty and humane political novel never ignores the fact that they could do a lot worse.

Nicholas Mosley’s Impossible Object is a series of eight linked epsiodes in which (the blurb is helpful) “Two characters who fall in love are seen in different aspects at different times and by different narrators.” Some of the times it is very hard to tell what is going on or who is going on about it; aware that, as with some recent French novels, this is the point, I am yet doubtful of the point of the point. As a whole, Impossible Object doesn’t come off, partly because of the inordinately pretentious inter-chapters, and partly because such an episode as “A Morning in the Life of Intelligent People” is nothing but a Pyrrhic victory over some tame unintelligents. “Both he and she believed in Freud”—their creator’s superiority is here too effortless. But in other episodes, the human concerns deploy themselves with more recalcitrance, with less willingness to let a novel have things all its own way. “Family Game,” in particular, is first-rate—very disturbing and very sane. So that doing right by the book may entail wronging the author, ignoring his strained scheme, and selecting a few memorable short stories.

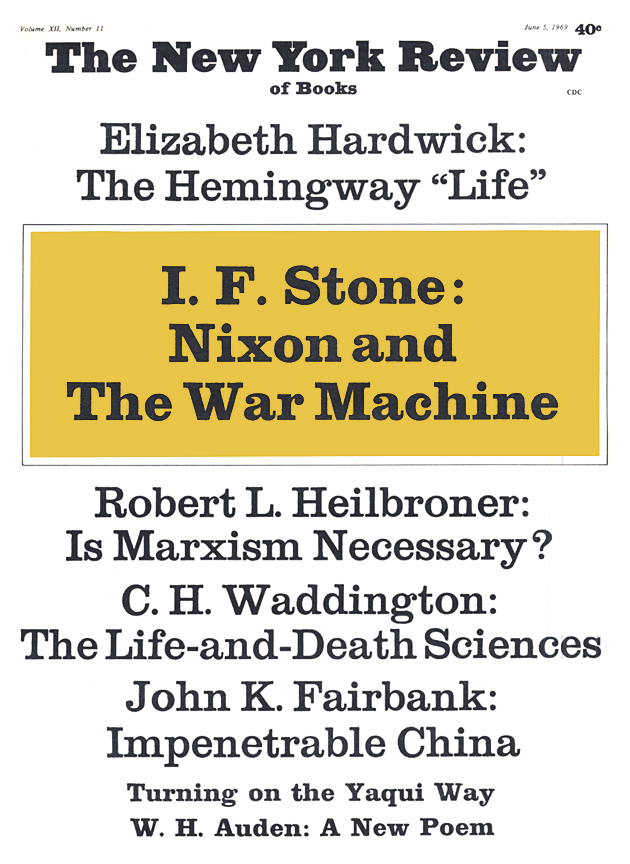

This Issue

June 5, 1969