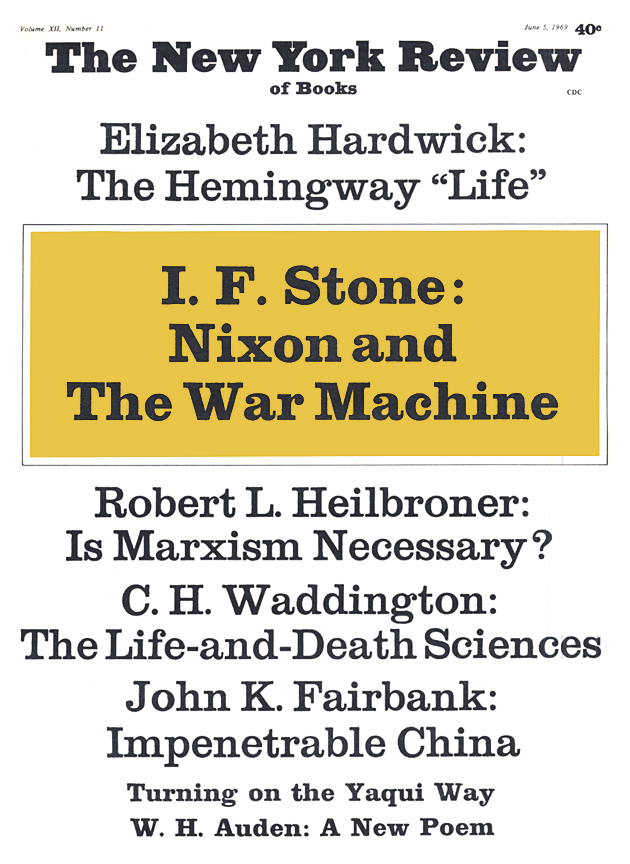

In government the budget is the message. Washington’s heart is where the tax dollar goes. When President Nixon finally, and very tardily, presented his first budget proposals in mid-April in a mini-State of the Union message, he said “Peace has been the first priority.” But the figures showed that the first concern of the new Administration, as of the last, was still the care and feeding of the war machine.

Only Nixon’s style had changed. “Sufficiency” rather than “superiority” in nuclear armaments remained the new watchword. But in practice it was difficult to tell them apart. Administrations change, but the Pentagon remains at the head of the table. Nixon’s semantics recalled John F. Kennedy’s eight years earlier. The Eisenhower Administration had waged battle for four years against the bomber gap and the missile gap with the slogan of “sufficiency.” “Only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt,” was Kennedy’s elegant riposte in his Inaugural, signaling a new spiral upward in the arms race, “can we be certain without doubt that they will never be employed.” The rhetoric was fresh but the idea was no different from John Foster Dulles’s “position of strength.” This is the plus ca change of American government and diplomacy. It emerged intact after Nixon’s first three months in office, too.

At a press conference four days after his budget message, Nixon said again that “sufficiency” in weaponry was “all that is necessary.” But a moment later he was clearly equating it with nuclear superiority. He said he didn’t want “the diplomatic credibility” of a future President in a crisis like that over Cuba’s missiles “impaired because the United States was in a second-class or inferior position.” A press corps obsessed with the latest plane incident off North Korea did not pause to consider the implications. Was “diplomatic credibility” to be measured in megatons? Were we preparing again to play a thermonuclear game of “chicken,” to see who would blink first at the prospect of instant incineration? Was this not the diplomacy of brinkmanship and the strategy of permanent arms race?

No correspondent asked these questions, and Nixon did not spell out the inferences. His tone was softer, his language more opaque, than that of the campaign, but the essential “security gap” theme had not changed. The main emphasis of Nixon’s first months in office, the main idea he tried to sell the country, turned out to be that it was in mortal peril of a Soviet first-strike capacity. The new Administration sought to overcome a mounting wave of opposition to the ABM and to the military generally, by ringing the bells of panic.

True, the Secretary of State often seemed to deny the perils the Secretary of Defense painted. Which was the party line? It was indicative that when visiting editors were given a press kit on the ABM April 7, with a covering letter on White House stationery, signed by Herbert G. Klein as Nixon’s “Director of Communications,” the only thing new in that kit, the only news it contained, and the one bit on which nobody commented, was the “document” the Administration had chosen as the first item. It was a reproduction of a column in which Joseph Alsop three days earlier had exuberantly portrayed the “grim” (a favorite Alsop word) dangers of a first strike from Laird’s new monster, the Soviet SS-9. The leading journalistic Pied Piper of the Bomber Gap and the Missile Gap had been enlisted by the new Administration to help it to propagate a new Gap. If the White House stationery and the Klein signature were not enough to make Alsop’s nightmare official doctrine, the reproduction of the column carried at the bottom of the page this imprimatur, “Prepared under the direction of the Republican National Committee, 1625 Eye St. N.W., Washington, D.C.” The candor was dazzling.

The Budget Bureau fact sheets which accompanied Nixon’s spending proposals sought to create the impression that on the military budget, as on so much else, Nixon in power was reversing the course set by Nixon on campaign. “Military and military assistance programs account for $1.1 billion (27%) of the $4.0 billion outlay reduction [for fiscal 1970],” said one fact sheet, “and $3.0 billion (55%) of the cut in budget authority.” But, as we shall see, while the cuts in domestic civilian programs proved all too real, those in the military budget were either dubious or deferrals.

There was in the Nixon budget one complete and dramatic about-face—on the FB-111. Six months earlier, just before the election, at Fort Worth, where General Dynamics was building this new strategic bomber, Nixon had promised to make the F-111 “one of the foundations of our air supremacy.” Now it was put permanently on the shelf. Procurement of the bomber was cut back sharply for fiscal 1969, which ends June 30, and abandoned altogether for fiscal 1970. Only the F-111D, the Air Force fighter version of this plane, was to stay in production a while longer.

Advertisement

Thus finis was soon to be written to the career of the multi-purpose, multiservice plane originally known as the TFX, one of McNamara’s most costly misjudgments. But on this, as on almost every other item of apparent economy in the Nixon-Laird revisions of the Pentagon’s budget, the few hundred millions saved in fiscal ’69 and ’70 were linked to commitments which would cost literally billions more in the decade ahead. Every short step back hid another leap forward in expenditures.

The TFX was McNamara’s effort to stall of the drive of the bomber generals to commit the country to an entirely new manned bomber in the missile age. He gave them the FB-111, the bomber version of the TFX, instead. Laird reduced FB-111 procurement in fiscal ’69 by $107 million and eliminated altogether the planned outlay of $321 million in fiscal ’70. But he then added $23 million for fiscal ’70 to speed “full scale engineering” of the new intercontinental bomber AMSA (Advanced Manned Strategic Aircraft) for which the Air Force and the aviation industry have been lobbying for years. “The FB111,” Laird told the Senate Armed Services Committee March 15, in an echo of the lobby’s arguments, “will not meet the requirements of a true intercontinental bomber and the cost per unit has reached a point where an AMSA must be considered to fill the void.”

It will be quite a void. The cost overruns, which had more than doubled the price of the FB-111, now became the excuse for going ahead with a far more expensive bomber. The net saving of $405 million in fiscal ’69 and ’70 ($107 plus $321 minus $23 million) will commit the country to a new plane which Senator Proxmire told the Senate April 22 will cost at least $24 billion during the next decade. Such illusory economies place heavy first mortgages on the future in favor of the military and at the expense of social needs.

Even so, there was hidden in the F-111 cutback a $200 million consolation prize for General Dynamics. The formal budget document1 carried an increase of $155.7 million for “Production of F-111D at minimum sustaining rate related to FB-111 cancellation.” I was puzzled by this reference to a “sustaining rate.” What was being “sustained”—military needs or General Dynamics?

I found a fuller explanation when Aviation Week & Space Technology arrived for May 5. It said the revised Nixon procurement plans for General Dynamics F-111D provided $599.8 million for aircraft “plus $56 million for advance procurement and $71.4 million to cover excess costs generated in fiscal 1968.” It said the total of $727.2 million “represented a sharp increase over original fiscal 1970 plans of $518 million.” Indeed this is an increase, though Aviation Week did not say so, of $209.2 million rather than the $155.7 specified in the budget message.

The increase had been approved by Deputy Defense Secretary David Packard—a director of General Dynamics until his Pentagon appointment—to counterbalance a cut of $320.9 million in the FB-111 program. It would “enable General Dynamics to retain its present production facilities.” Not only did thirteen of these fighter planes crash in their twenty-six months of operations2 but Senator Curtis of Kansas, in a comprehensive Senate speech last October 3, said they were not maneuverable enough as fighters. They are effective only as tactical bombers against enemy forces like those in Vietnam, which have no air cover of their own. Yet the government was not cutting back on its original plan to buy 331 of these F-111D’s.

This is only one of many examples in the budget of how easily the Nixon Administration finds millions for such dubious military purposes but not for urgent social needs. The $200 million consolation for General Dynamics is the same amount—a very inadequate amount—Nixon set aside in his budget message for riot-devastated cities. Nixon got a lot of publicity out of his order to give this urban program priority, but it didn’t have enough priority to be a $200 million addition to the budget. It was just deducted from the meager amounts already available for other urban purposes.

II

Those who still look for the “shape” of the Nixon Administration are bound to remain bewildered. Shape is another word for policy, and policy requires the substitution of decision for drift. The campaign promised decision from one direction, the right. The situation requires decision from another direction, which might be called the left. Nixon turns out to take his stand—though that is too strong a word—in the middle of makeshift compromises. Whether on electoral reform or tax reform or poverty, feeble and inadequate half-measures are the rule. This shapelessness is the shape of the new Administration.

Hand-to-mouth decisions are standard in all governments, and inertia is basic in politics as in physics. But drift is only safe in quiet waters; to let inertia have its way in stormy seas is to risk disaster. Richard Nixon in the Sixties is beginning to resemble Calvin Coolidge in the Twenties, when the country kept cool with Cal, just before going over the brink with the stock market crash and the Great Depression.

Advertisement

To let inertia reign in the American government is also to let the military dominate. The sheer size of the military establishment, its vast propaganda resources and its powerful allies in every business, locality, and labor union affected by the billions it spends every year, gives it momentum sufficient to roll over every other department and branch of the government. In the absence of a strong hand and hard choices in the White House, the Pentagon inevitably makes the decisions. If nothing else, it makes them by default.

But there is more than default, and more than meets the eye, in the military budget. The readiest source of campaign funds and political support for nomination and election as President lies in the military-industrial complex. It is also the most skillfully hidden source. I suspect that the 1968 campaign, like the 1960, was preceded by deals which called for a buildup in military procurement. This would help to account for the steep increase in appropriations by the Kennedy Administration despite its discovery on taking office that the “missile gap” did not exist.3

The two plums the military-industrial complex most wanted on the eve of the 1968 campaign was the ABM and AMSA, a new advanced strategic bomber. In 1966 the Armed Services Committees of both houses recommended extra funds to speed both projects. A Congress still comatose on military matters dutifully voted the money. But McNamara refused to spend it. Johnson made two moves during the following year which cleared the way for both projects. In September 1967 he forced McNamara to swallow the bitter pill of advocating a “thin” ABM system in which the Secretary of Defense clearly disbelieved. Two months later Johnson made the surprise announcement—as much a surprise to McNamara as to the press—that he was shifting the redoubtable Pentagon chief to the World Bank. That cleared the way for AMSA, too, and with both projects it also cleared the way for the 1968 campaign.

As late as January 1968, in his last posture statement as Secretary of Defense, McNamara was still fighting a rear-guard action against AMSA. He argued that the principal problem lay in the growing sophistication of Soviet air defenses. “Repeated examination of this problem,” he told Congress, “has convinced us that what is important here is not a new aircraft but rather new weapons and penetration devices.”

AMSA began to inch forward when Clifford replaced McNamara. In Clifford’s first posture statement last January, he struck a new note when he declared the FB-111 would be too small to carry the new weapons and penetration devices McNamara had in mind. One wishes one knew more about this, since it seems unlikely that McNamara would have overlooked so simple a point. While Clifford said “we are still uncertain whether a new intercontinental bomber will be needed in the 1970s,” he more than doubled the research and development funds for AMSA, increasing them from $30 million in fiscal 1969 to $77 million in fiscal 1970, “to keep the program moving.”

The Nixon-Laird revisions two months later went further. They not only added $23 million more for AMSA but authorized the Air Force to move into the engineering phase, the last stage in R and D before procurement. “Now, after a very careful review,” Laird told the Senate Armed Services Committee March 27, “we have decided to cut off the FB-111 program…and concentrate our efforts on the development of a new strategic bomber, AMSA.” General Dynamics, which lost out when Nixon phased out FB-111, will be one of the bidders on AMSA.

ABM and AMS together could spell $100 billions in electronic and aviation contracts in the years ahead. AMSA itself may prove a bigger gamble and a far more costly error than the TFX. Space/Aeronautics for January published a special issue plotting future trends in strategic warfare. It pointed out some of the pitfalls which may lie ahead for AMSA. About eight years elapse between concept definition and actual production in developing a new bomber. But Pentagon intelligence has never been able to come up with estimates of enemy threat valid for more than two or three years. “Thus,” this Conover-Mast publication for the aerospace industry concluded, “there is no way of telling, the critics of AMSA claim, whether we would be committing ourselves to a system we really need or to what will end up as an immensely costly mistake.”

The survey admitted that AMSA would be “less vulnerable than the B-52 and perform better,” but added philosophically that “in a nuclear exchange time is too important an element for bombers to have any real effect.” In other words even the fastest bomber may have no targets left after the far swifter missile exchange is over. One firm intelligence forecast emerged from the survey. “If AMSA is built,” Space/Aeronautics said, “it will probably be our last strategic bomber. Once the present generation of Air Force commanders is gone, the top-level manpower will not be there to produce the sort of pressure that has kept AMSA alive for so long.” Once the bomber admirals are dead, the clamor for a new bomber will die out, too. But the last fly-by will cost plenty.

III

AMSA is only one of many new military projects hidden in the new 1970 budget which will add billions to the future costs of government. “The present inflationary surge, already in its fourth year,” Nixon said in his April 14 message, “represents a national self-indulgence we cannot afford any longer.” But the principal beneficiaries of that indulgence are the military and their suppliers. And they seem to be exempt from anti-inflationary measures.

Fully to appreciate what the military is getting one has to begin with a disclosure made in the Budget Bureau’s presentation of Nixon’s budget revisions. Nixon had to squeeze $7.3 billions out of the normal civilian and welfare activities of the government in fiscal 1969 (which ends June 30 of this year) in order to meet the expenditure ceilings imposed by Congress when it enacted the 10 percent surplus income tax. This reduction over and above Johnson’s budget for FY 1969 was made necessary by certain “uncontrollable” items. An example is the interest on the public debt which rose by $300 millions. But the biggest uncontrollable item, ten times that much, or $3 billion, was an increase in Vietnam war costs over and above those originally estimated by Johnson.

So all sorts of civilian services during the current fiscal year have had to be pared to meet the unexpected increase in the cost of the Vietnam war. Now let us couple this revelation about the 1969 budget with a basic decision made by Johnson in the 1970 budget. In that budget Johnson for the first time, on the basis of his decision to end the bombing of the North, which was very costly, and perhaps in expectation of less combat on the ground in the South,4 forecast the first sharp cutback in Vietnam war costs. This was estimated as a saving of $3.5 billion during fiscal 1970.

This was to be the country’s first “peace dividend.” But instead of applying this $3.5 billion in the 1970 budget to starved civilian and welfare services, or to reduction of the deficit, Johnson added this $3.5 billion and $660 million more to the money available for the Pentagon to spend on procurement and activities other than those connected with the Vietnam war. The total increase in the non-Vietnamese military budget as projected by Johnson was $4.1 billion more, even though he estimated the Vietnam war was going to cost $3.5 billion less.5 In his April 14 message, Nixon said of our domestic needs, “what we are able to do will depend in large measure on the prospects for an early end to the war in Vietnam.” The Johnson 1970 budget projected the first slowdown but proposed to use the savings entirely for military expansion. Nixon went along with that decision.

From the Pentagon’s point of view there could not have been a smoother transition than the shift from Johnson to Nixon. Nixon revised Johnson’s social and welfare programs downward but left his military budget essentially untouched. It read like the handiwork of the Johnson who was the ally of the military and the armament industries as chairman of the Senate Preparedness subcommittee during the Fifties. Johnson’s last defense budget was not only the highest ever sent Congress—$81.5 billion as compared with the World War II peak of $80 billion in fiscal 1945—but laid the basis for a huge expansion in spending during future years. It gave the go-ahead signal to a wide variety of projects the armed services had long desired.

Nixon had campaigned on a “security gap” but Johnson left few if any gaps to fill. “The number of new programs spread through the new defense budget,” Space/Aeronautics commented in its February issue, “is astounding in comparison with the lean years from fiscal 1965 to 1969.” Among them were $400 million for “major developmental activity on no fewer than six new aircraft’ and—biggest item of all—an increase of $1.64 billion to a total of $2.85 billion for the Navy’s surface ship and submarine building program. Arms research and development was boosted $850 million to a total of $5.6 billion, including work on such new monsters as missiles which can be hidden on the ocean floor.

This farewell budget also put Nixon in a bind. As Space/Aeronautics pointed out in that same editorial, if Nixon tried to cut back appreciably on the Johnson budget, he would open himself to “security gap” charges. On the other hand “if he doesn’t defer or cancel at least some of them, and if the war in Vietnam cannot be brought to an honorable close some time next year, he will face a crushing arms bill in fiscal 1971, when many of these starts begin to demand more money.’ That was the risk Nixon and Laird preferred to take.

IV

Nixon claims to have cut $4 billion from 1970 outlays, and taken $1.1 billion, or 27 percent, from the military. Critics have protested that he took $3 from civilian needs for every $1 he took from the military. But even this is illusory.

From another point of view, even if we accept the Nixon cuts at face value, the military will have $3 billion more in fiscal 1970 for non-Vietnamese war purposes than it had in fiscal 1969. We have seen that Johnson budgeted a $3.5 billion cut in Vietnam war costs for fiscal ’70 and then added $4.1 billion to the military budget for projects unconnected with the Vietnam war. If you deduct Nixon’s $1.1 billion from that $4.1 billion, the Pentagon is still ahead by $3 billion.6 If Nixon had applied the whole projected saving of $3.5 billion on Vietnam to civilian use or deficit reduction, the fiscal 1970 total for national defense would have been reduced to $97,499 million. All Nixon did was to cut the Johnson increase by a fourth.

Even this may turn out to be—at least in part—a familiar bit of flim-flam. Since Johnson began to bomb the. North in 1965 and take over the combat war in the South, almost every annual budget has underestimated Vietnamese war costs. These have had to be covered later in the fiscal year by supplemental appropriations. The under-estimate in fiscal 1969, as we have seen, was $3 billion. The fiscal 1970 budget is running true to form.

The biggest “economy” item in the Nixon military budget is $1,083.4 million, which is attributed to “reduced estimates of ammunition consumption rates.”7 Just how much of the estimated $1.1 billion “saving” in outlays for fiscal 1970 will be the result of lower consumption of ammunition in Vietnam was not made clear. The $1.083.4 million is given as a net reduction of obligational authority in fiscal 1969 and 1970. It is one of the three main items in that $3 billion cut in obligational authority for fiscal 1970 which make it possible for the new Administration to claim that 55 percent of the total cut in obligational authority for 1970 ($5.5 billion) came from the military. Obligational authority is not necessarily or entirely translated into actual outlays during the fiscal year in which it is granted.

This projected cut in the rate of ammunition consumption is in addition to Johnson’s projected cut of $3.5 billion in Vietnam war costs. Though Laird does not blush easily, even he seems to have been embarrassed by this particular “economy.” “To be perfectly frank,” said Laird, who rarely is, when he first broached this item to the House Armed Services Committee on March 27, “I think the ammunition consumption rates for Southeast Asia are based on rather optimistic assumptions, particularly in view of the current Têt offensive.” Yet, under pressure from the White House to show more economy, the optimism rose sharply in the next four days. The following table shows the change in estimated savings for ammunition and its transportation in millions of dollars in those four days:

These figures are for total obligational authority for fiscal years 1969 and 1970. Perhaps the Administration hesitated to make public its actual outlay estimates for these two years, since they may easily turn out to be higher rather than lower, and may have to be met later in the year by a supplemental appropriation. Between March 27 and April 1 Laird boosted the estimated reduction in total military outlays for FY 1970 from “about $500 million” to $1,113 million. Most of the increased “economy” seems to have come from this ammunition item.

There are several indications in the official presentations themselves which lead one to think Laird was right to be queasy. The original 1970 budget projected consumption of 105,000 tons a month in ground munitions through December 1970. Actual consumption in January was given as 96,000 tons, but that was before the recent enemy offensive got under way. The consumption of ammunition must have risen sharply with the fighting in February, March, and April, but when I asked the Pentagon for the monthly figures since January, I was told they could not be given out. “We can only say,” an official spokesman told me, “that the Secretary’s projections are being borne out.” If that is true our troops must have been meeting enemy attacks with switch knives.

Another indication—how I love tracking down these liars!—appears in what we know about the volume of bombs dropped on South Vietnam and Laos since we stopped bombing the North. The Pentagon’s own figures on total tonnages dropped show little change. Total tonnages dropped in September and October last year, before the bombing of the North stopped, were almost 240,000. Total tonnage dropped in January and February of this year, when it was dropped only on Laos and South Vietnam, was more than 245,000. There was an increase of 5,000 tons. That increase makes the estimate of a saving of more than a half billion dollars in air munitions for fiscal ’69 and ’70 look very phony indeed.

Laird himself said consumption of air munitions was rising. On March 27 he told the House Armed Services Committee that while consumption had been estimated at 110,000 tons per month for the twenty-four months from January 1969 to December 1970—that doesn’t sound like much deescalation ahead, at least in the air!—“actual consumption is now running at about 129,000 tons per month.” Yet he projected a saving of $42.5 million on air munitions in fiscal 1969 and $375.4 in fiscal 1970. When he got back to the committee four days later, he placed actual consumption even higher, at 130,000 tons a month, but also projected higher savings! Now he was to save $89.5 million on air munitions in fiscal 1969, or twice the figure four days earlier; and $442 million for fiscal 1970, an increase of $47 million over the earlier estimate. Yet Laird said he saw “no indication that consumption will decline by very much during the next twelve-to-eighteen months.” How then were expenditures on air ammunition to be lower than expected when the tonnage of bombs dropped was running higher than expected? Non-Euclidean geometry is not half so exotic as Pentagon arithmetic.

The ammunition figures for Vietnam are stupendous. The original Johnson-Clifford ’70 budget in January projected the cost of ammunition in Vietnam during fiscal 1970 at $3.2 billion. This expenditure of shot and shell over Vietnam is two-and-a-half times the total 1970 revised Nixon budget of $2 billion for the Office of Economic Opportunity (down $132 million), and more than twice the revised elementary and secondary education outlay for ’70 which he set at $2.3 billion (down another $100 million).

V

After this razzle-dazzle on ammunition, the next largest item of military saving in the Nixon-Laird budget revisions is the ABM. Let us return to the formal document sent Congress by the President. There on page 178 are given “principal changes in 1970 budget authority resulting from 1969 and 1970 Defense program changes.” The second largest of these is $994 million for “Reorientation of the antiballistic missile program to the new Safeguard system.” This and the ammunition item make up almost $2.1 billion of that $3 billion cut in military obligational authority on which the new Administration commends itself.

A businessman in financial difficulties who thought up such savings for his stockholders would soon be in jail for embezzlement. The “reorientation” of Sentinel into Safeguard may reduce spending in fiscal 1970 but only by adding at least $1.5 billion and possibly $5.5 billion more in the next few years. This is an expensive rebaptism or, better, if we consider the phallic significance of these monsters, re-circumcision. Nixon had an easy way out of the ABM fight if he wanted one. He could have announced that like Eisenhower he had decided to keep the ABM in research and development until he was sure it would not be obsolete before it was deployed.

If he had been a little more daring, and a little less beholden to the military-industrial complex, he might have cut billions9 from the military budget immediately by offering a freeze on all new deployment of strategic defensive and offensive missiles if the Russians did likewise as a preparation for strategic arms negotiations. This would not only save at least $5 or $6 billion in the new fiscal year but ensure our present nuclear superiority and fully guarantee against first strike nightmares.10

Nixon chose instead a tricky stretch-out. This offered some reductions in the new fiscal year, as compared with Johnson’s ABM proposal, but at the expense of higher costs later. This ingenious compromise made it possible to offer an apparent saving to the taxpayer and larger eventual orders to the electronics and missile industries. This not only fulfilled the Administration’s promise of New Directions but enabled it to move in opposite directions at the same time. Johnson’s Sentinel was estimated to cost $5.5 billion; Nixon’s Safeguard, variously from $6.7 to $7 billion, or $1.5 billion more. This may prove another official underestimate. An authoritative service which covers all developing major weapons and aerospace systems for industrial and governmental subscribers places the total cost of Safeguard much higher.

This is DMS, Inc. (Defense Marketing Service), a ten-year-old service now a part of McGraw-Hill. I had never heard of it until an anonymous reader sent me a reproduction of its report on Nixon’s Safeguard. I checked with its Washington office by telephone and was given permission to quote it. Its detailed analysis places the total cost of the system at $11 billion and ends by warning that “in a program as complex as Safeguard, historical experience indicates costs in the long run are likely to be considerably higher.” When Senator Cooper put the DMS analysis into the Congressional Record May 8, he noted that it did not include “about $1 billion AEC warhead costs.” This would bring the total cost of Nixon’s Safeguard past $12 billion.

Since the ABM authorization will soon be before Congress and this defense marketing service is known only to a restricted circle, we give its computations here:

The DMS report notes that we have already spent $4.5 billion on the ABM from fiscal 1956 when the Army started the Nike Zeus program, through fiscal 1968, and that the research efforts which made Nike-Zeus obsolete before it could be deployed are still going on, at a cost of $350 to $500 million annually. “A number of new concepts as well as hardware,” the report said, “are currently under investigation.” These threaten Safeguard with obsolescence too. “Preliminary research,” DMS said, “has pointed the way toward the following types of advances”: One was radars of much higher frequency so the interception “would be made with either a much smaller nuclear warhead or even a conventional high explosive charge.” Another was a new third stage for Spartan so the missile could fly out at greater ranges and “maneuver through a cloud of decoys to find and destroy the real warhead.” A third—most expensive of all—was “defensive missiles carried either in ships or large aircraft deployed closer to the enemy’s launching sites.”

We give these details to show that in embarking on the ABM we are embarking on a wholly new sector of the arms race with a high rate of obsolescence to gladden the hearts of the electronics companies and of A.T.&T., whose Western Electric has long been the main contractor. The reader should note that the three advances cited in the DMS report are relatively simple and forseeable developments. All kinds of “far-out” possibilities are also being investigated. The secret hope which lies behind all this Rube Goldberg hardware is that some day somebody will turn up a perfect ABM defense and thus enable the possessor to rule the world because a power so armed can threaten a first strike, knowing it will be immune to retaliation.

The most candid expression of this viewpoint was made by Senator Russell during the defense appropriations hearings in May of last year. “I have often said,” Senator Russell observed, “that I feel that the first country to deploy an effective ABM system and an effective ASW [anti-submarine warfare] system is going to control the world militarily.”11 This control of the world, however, may be on a somewhat reduced basis. Six months later, during the Senate’s secret session on the ABM (November 1, 1968), Senator Russell admitted, “there is no system ever devised which will afford complete protection against any multiple firing of ballistic missiles…we will have no absolutely foolproof defense, I do not care how much money we spend on one, or what we do.” Senator Clark replied that casualties would be so high as to destroy civilization “and if there are a few people living in caves after that, it does not make much difference.” To which Russell made his now famous rejoinder, “If we have to start over again with another Adam and Eve, I want them to be Americans and not Russians.” (Congressional Record, E9644, November 1, 1968.) Thus we would at last achieve an unchallengeable Pax Americana! And thus the ABM turns out to be another variant of the military’s unquenchable dream of an Ultimate Weapon, to leap some day like a jackpot from a slot machine if only they go on pouring money into R and D.

VI

I would ask the reader’s indulgence for one more foray into the labyrinthine depths of the Pentagon budget. Deeper knowledge of these recesses is necessary if we are ever to hunt down and slay the dragon. I want to deal with the next largest source of the Nixon military “economies.” These involve deferrals of expenditures amounting to about $480 million. Most critical comment has been content to note that mere deferral of spending is not real economy, since what is saved in fiscal ’70 will be spent later. There is a more important point to be made. These deferrals, if closely examined, provide additional proof of how recklessly and wastefully the Pentagon dashes into production before full testing and evaluation have been completed, before it knows, in other words, that these expensive weapons will work. We will see how much pressure it takes to make the Pentagon admit this elementary error.

To grasp the full significance of these so-called “economies” of Nixon and Laird we must see them against the background of revelations by two Senators, one the leading pillar of the military in the Senate establishment, Senator Russell; the other, a former Secretary of and long-time spokesman for the Air Force, who has turned against the military-industrial establishment, Senator Symington.

During the secret debate on the ABM last November 1, Russell told the Senate one of the “most serious mistakes” he had ever made as Chairman of the Armed Services Committee, which passes on all military requests for authorization, and as chairman of the Senate subcommittee, which passes on all defense appropriations, “was in allotting vast sums to the Navy for missile frigates before we knew we had a missile that would work on them.” He said “we built missile frigates, we built missile destroyers and missile escort ships” on the basis of “unqualified” testimony of “everyone in the Department of Defense and in the Navy” that effective missiles were being developed. “It probably cost the taxpayers,” Russell said, “$1 billion, because they have had to rebuild those missiles three times.”

A more comprehensive statement of the same kind was made to the Senate by Symington on March 7 of this year. He put a table into the Congressional Record (at page S2464 that day) which showed how much had been spent on missiles in the past sixteen years which were no longer deployed, or never had been deployed, because of obsolescence. The total was fantastic. Symington gave the names, the expenditures, and the life-span of each missile. The total cost of those no longer deployed was $18.9 billion and the cost of those which were abandoned as obsolete or unworkable before deployment was $4.2 billion. The total was $23 billion. Imagine what those wasted billions could have done for our blighted cities!

Symington’s table was introduced to underscore his point—buttressed by past testimony from McNamara—that the ABM would soon be another monument to this kind of expensive obsolescence. Another inference to be drawn from this table is how many billions might have been saved if the Pentagon had not rushed so quickly into these miscarriages. Behind the glamorous names which flashed through the appropriations hearings and the ads in the aeronautical and military trade journals—Navaho, Snark, Dove, Triton, and even Plato (what did he do to deserve this honor?)—lies an untold story of beguiling missile salesmanship and drunken-sailor procurement methods. It might be worth billions in future savings if a Congressional investigating committee really dug up the full story and its lessons.

The need for such an investigation becomes plain if one examines the funny thing which happened to SRAM (acronym for short-range attack missile) on Secretary Laird’s way to and from the budget forum on Capitol Hill between March 27, his first appearance before the House Armed Services Committee, and his second appearance on April 1, just four days later. SRAM is one of the new missiles which have been under development. It is supposed to be mounted on a bomber so it can be rocketed into enemy territory from a position more than a hundred miles away from the enemy’s defense perimeter. The idea is to circumvent the enemy’s defenses by stopping the bomber out of their range and lobbing the missiles over them.

SRAM has had several predecessors, all expensive, of course; it is not a simple contraption. The predecessors appear in Senator Symington’s table. Crossbow, Rascal, and Skybolt were earlier attempts at a stand-off missile; they cost a total of $962.6 million before they were abandoned prior to deployment. Hound Dog A, which cost another $255 million, is another missile in the same family which is no longer deployed. SRAM is very different in capability, range, and complexity. SRAM is intended to do for the bombing plane what penetration aids do for the ICBM. SRAM is supposed to carry all kinds of devices to confuse the radars of the enemy defense.

When Laird appeared before the House Armed Services Committee on March 27 he referred, without further explanation, to “delays experienced in the SRAM development production program.” The original Johnson-Clifford budget last January for fiscal 1970 called for the modification of all seventeen B-52 squadrons of series G and H at a total cost of about $340 million to enable them to carry SRAM. The “modification kits,” as Laird described them, were to be bought from Boeing “at a total cost of about $220 million,” and it was planned to buy kits for twelve squadrons in 1970, leaving the rest to be modified in 1971. Laird proposed to save $30 million in fiscal ’70 by equipping only ten squadrons in ’70 and the remaining seven in ’71. He said “This change will give us a smoother program.”

But the White House and the Budget Bureau, desperate for ways to cut, put pressure on the Pentagon and four days later Laird was back before the Armed Services Committee. Now instead of $30 million he proposed a deferral of the SRAM program amounting to $326 million. It now appeared that he had been less than candid with the committee. The cryptic references to “delays” turned out to be quite an understatement. He came forward with new changes in the SRAM program, all of them—he explained—“related to the difficulties encountered in the development of this Short Range Attack Missile.” Now it was not “delays,” but “difficulties.”

Laird went on to quite a revelation. “We have now reached the conclusion,” he told the committee, “that procurement of operational missiles should be deferred until the test program conclusively demonstrated that they will work as intended.” So “we have deleted most [but not all!] of the missile procurement funds” from fiscal ’69 and ’70, for a total cut in the two years of $153 million.

Then he proposed to defer not only the missiles but the modifications designed to enable the B-52s to carry them. “Inasmuch as we do not know when operational missiles will be available,” Laird said, “we have also deferred all special SRAM modification work on the B-52s and FB-111s.” The total net deferral—after adding $17 million to R and D for “a greater portion of the overhead cost” (another consolation fee?)—was to be $326 million.

This shows how much pressure it takes to squeeze the fat out of the military budget, and a little more candor out of the Pentagon. Why didn’t Laird tell the committee on March 27 what he revealed on April 1? But for the extra pressure, the Pentagon would have gone on with procurement of the SRAM before knowing whether it would work, and with modification of the strategic bombers to carry the missiles before it was sure that it would have the missiles. What if further testing modifies the missile, and this requires a change also in the kits which modify the planes to carry these missiles? Why risk the waste of millions?

The SRAM story raises similar questions about Laird’s rather cryptic references in his budget presentation to a similar deferral of “about $160 million” in the Minuteman ICBM program. The most important part of that “saving” is due, as Laird told House Armed Services on March 27, to “a slowdown in the deployment of Minuteman III.” This is the Minuteman which will carry MIRV—“multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles,” i.e., additional warheads independently targeted. It was tested for the first time last August 16 with three warheads. 12 “While we are confident,” Laird said, “that the Minuteman III will perform as intended, we believe it would be prudent to reduce somewhat the previously planned deployment rate, at least through the FY 1970 procurement lead-time.” Why only somewhat, and what does somewhat mean for the whole program? “This delay,” Laird went on, “would serve to reduce the amount of overlapping of R & D and production and provide more time for production.” Why risk overlapping altogether until testing has been completed? Laird himself said he was planning to accelerate operational testing “to help ensure that the missile is working well before we return to the originally planned rate in FY 1971.” “Mr. Chairman,” Laird said, patting himself warmly on the back, “this reflects our determination to minimize cost overruns resulting from R and D modifications after production has commenced.” But perhaps more serious cost overruns could be avoided if Minuteman III, like SRAM, were subjected to further deferrals.

A franker if ironic account of the Minuteman III cuts appeared May 5 in Aviation Week. It says “The reason for the reduction is fear of reliability problems with the new missile.” It said the Air Force had “decided ‘to reduce the concurrency of development and production’ of the missile in order to insure reliability of all components.” Even the Foreign Service could not have hit upon a smoother phrase to equal that “concurrency of development and production.” Aviation Week added, “The cutback was publicized by some Defense Dept sources as evidence of US willingness to reduce strategic offensive armaments prior to arms reduction talks with the Soviets, but that was not the reason.”

This effort to make the Minuteman cuts look like evidence of Pentagon enthusiasm for arms talks originated in Laird’s own presentation on April 1. In a super-slick conclusion he told the Committee, “Our decision to slow the Minuteman III deployment—though necessitated for other reasons—provides a period of time in which arms limitation agreements could become effective at a lower level of armaments…. It remains to be seen, of course, whether our potential adversaries will similarly indicate with actions that they, too, are serious about desiring meaningful arms limitation talks.” These are the moments when Laird sounds as if he were dreamed up by Molière.

But beyond any question of personality or politics, the almost irresistible momentum of the military machine which is slowly transforming American society finds its ultimate rationale in the theory of deterrence. It is to this and the permanent arms race it generates that I would like to turn in a concluding article.

(This is another in a series of articles by I. F. Stone on the military-industrial complex.)

This Issue

June 5, 1969

-

1

House Document No. 91-100. 91st Congress, 1st Session. Reductions in 1970 Budget Requests. Communication from the President of the United States, p. 17. ↩

-

2

AP in Omaha World Herald, March 7, 1969. ↩

-

3

Carl Kaysen, who was Kennedy’s Deputy Special Assistant for National Security Affairs, has given us more precise figures than I have ever seen before in the chapter on “Military Strategy, Military Forces and Arms Control” in the Brookings Institution symposium, Agenda For The Nation (Doubleday, 1969). He wrote (pp. 562-3) that the decisions of 1961 and 1962 by Kennedy “called for the buildup by 1965 of a US strategic force of nearly 1,800 missiles capable of reaching Soviet targets; somewhat more than a third were to be submarine-launched. In addition, some 600 long range bombers would be maintained. This was projected against an expected Soviet force of fewer than a third as many missiles and a quarter as many bombers capable of reaching the United States.” (Our italics.) The “overkill” was worth billions to the aviation and electronics industries. ↩

-

4

According to a little-noticed press release by Senator Stephen M. Young (D. Ohio), a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, which has access to much information otherwise secret, Johnson had originally planned a cutback of troops in Vietnam. Young asked Nixon to recall two divisions before July and more later with an announcement, “We have accomplished our objectives in Vietnam. Our boys are coming home.” Young said Johnson had decided on a similar announcement last year but was talked out of it by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. ↩

-

5

Since I have been challenged on this “peace dividend” by some colleagues, and others have wondered by what elaborate computation I arrived at it, I give the source, p. 74 of The Budget of the US Government for Fiscal 1970. It says, “As shown in the accompanying table outlays in support of South-east Asia are anticipated to drop for the first time in 1970—declining by $3.5 billion from 1969. This decline reflects changing patterns of combat activity and revised loss projections. Outlays for the military activities of the Department of Defense, excluding support of Southeast Asia, are expected to rise by $4.1 billion in 1970, to provide selected force improvements.” (Italics added.) ↩

-

6

Even that understates the case. Down near the bottom of the budget outlays table of the Nixon revisions is $2.8 billion more for “civilian and military pay increases.” (Our italics.) Laird in his April 1 presentation said this would add $2.5 billion but failed to make clear whether this was for the whole government or only for Pentagon civilian and military—almost half the civilian employees of the government work for the Pentagon. Clifford in his 1970 statement gave a figure of $1.8 billion for Pentagon pay increases but did not make clear whether this included the civilian employees. So pay raises will add between $1.8 billion and $2.5 billion to this $3 billion figure. ↩

-

7

See page 17 of House Document No. 91-100, 91st Congress, First Session. ↩

-

8

House Document No. 91-100. Reductions in 1970 Appropriation Request. Communication from the President together with details of the changes. 91st Congress, First Session. ↩

-

9

The Johnson budget for 1970 placed the expenditure for strategic forces at $9.6 billion as compared with $9.1 in 1969 and $7.6 in 1968. Much of this is for deployment of new weaponry. ↩

-

10

“Such a freeze,” Senator Percy declared in a speech April 17, “should be acceptable to the Defense Department. Secretary Laird has testified that our missiles on land and under the seas as well as our long-range bomber force present an overwhelming second-strike array. If a freeze—fully verifiable by both nations through satellite reconnaissance as well as other intelligence sources—is put into effect, the US deterrent will remain credible into the foreseeable future.” But if the deterrent remains credible, what will the poor missile salesman do? ↩

-

11

Department of the Army, Senate Hearings, Department of Defense Appropriations for fiscal 1969, 90th Congress, Second Session, Part II, page 868. ↩

-

12

“On August 16, said a special survey in Space/Aeronautics, page 88, last January, “Poseidon and Minuteman III were launched with ten and three warheads respectively.” ↩