To the Editors:

May I point out several recent developments in the prison and underground scene, as these affect nonviolent resistance to the war?

My brother, Father Philip Berrigan, and David Eberhardt are at Lewisburg Federal Prison at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, serving six and two year sentences for destruction of draft files in Baltimore and Catonsville, Maryland. Recently they have been consigned to solitary confinement in the prison, a facility with which your readers may be familiar; there, at present writing, they have been fasting for some two weeks, to protest their treatment and that of other resisters of war.* Supporters have arranged to visit the Federal Bureau of Prisons in Washington, and to demonstrate at Lewisburg. Some background information may be useful as revealing a trend, not only in the Federal Bureau, but in pressures brought on prisoners through the FBI.

I have refused to submit to arrest and imprisonment after conviction for draft file destruction at Catonsville in May of 1968, with eight others. Of the Catonsville Nine, one member, David Darst, is dead after an auto crash in November of 1969. All the others are in prison except Mary Moylan and myself. David and Philip evaded capture by the FBI for some ten days in April of this year. They were assigned to Lewisburg, under maximum security, contrary to the general practice of keeping nonviolent prisoners of peace in minimum security, either at Allenwood or the Lewisburg farm. The grounds for this move are strictly extrajudicial; they were told that the terms would not be negotiable, until Mary Moylan and myself were rounded up. Such treatment is evidently designed to put such pressures on Mary and myself as to force us to surrender; indeed, whenever my writings or interviews with the press or TV have come to public attention, or whenever the FBI has been frustrated in an attempt to locate me, some new act of repression has fallen on the two prisoners. May I point to one of these incidents (there have been several).

On June 27, approximately one hundred agents, supported by a fleet of radio cars and walkie-talkies, invaded the wedding of two friends in Baltimore in search of me. They searched the nave of the church, reception rooms, basements, and closets. Once a balloon used in the celebration popped; guns were drawn instinctively. The wedding was disrupted, departing guests were followed in police cars. I of course was nowhere to be seen. The next day, June 28, an interview with me appeared in the Sunday magazine section of The New York Times. It could not but be judged that FBI frustration would translate itself into more violence on more scenes, and would reach once more into Lewisburg Prison.

Now surely the FBI knows, from the several interviews I have published, from the opportunities freely offered newsmen to question my tactics and ethos and those of my friends, that neither I nor my associates have any skills in the use of armaments, light or heavy; nor have we any stomach for paramilitarizing our movement. The old question therefore arises yet once more: who is it, anyway, who induces violence, itches for it, invites it in others; in sum, makes it less and less possible for nonviolent men and women to survive? When the FBI broke into a Chicago apartment in June to capture George Mischi, another of the Catonsville Nine, they entered with drawn guns, though again (it goes without saying) he and his friends were unarmed. Indeed, I have been warned by an ex-agent of the Bureau that were I to offer resistance to proximate arrest or attempt to flee (neither of which I have any intention of doing), I would risk being shot.

One can only conclude that the time has arrived on the national scene, as well as the prison scene, when priests and Panthers are to be given the same treatment. I take a certain rueful satisfaction in this truth; the church is long overdue in sharing punishment habitually meted out to those who would bring change on an inhuman, violent, gunman scene, in prison as in public. My brother and I are fully prepared to pay the consequence of our resistance to war, in prison or in public. But we wish to place the question before Americans: must such consequences include the real threat of death or bodily injury to ourselves or those who work with us? Is the FBI subject to no law of the land, on limitation of violent means in regard to those who have consistently rejected violence as their tactic? Is the federal prison system subject to no law of the land, on limitation of vengeance against nonviolent resisters in prison? Or must such prisoners continue to be used as pawns by the authorities, until the nonviolent underground is brought to heel?

These last few weeks and their events have brought the sobering reflection home to me: I and others like me are no longer the objects of a traditional manhunt by forces of law and order. We are the objects of a search-and-destroy mission, borrowing its tactics from the military treatment of Vietnamese. There are no traditional civilized rules to this game any more; I can expect the worst, and so can my brother, my family, and friends.

In Lewisburg, my brother’s quarters were shaken down frequently, he was placed under suspicion for allegedly organizing a penal strike (though no evidence was ever brought forward), his mail was over-censored and returned to senders who had previously been approved as correspondents, informers among inmates were encouraged to report suspicious words, acts, or associations, a memorandum was issued to guards instructing them to watch him as a dangerous organizer, he was searched without warning or explanation, and the small room where he prepared for Mass was sacked (for firearms, explosives, writings?—no one knows).

The fact is [as he wrote], political prisoners at Lewisburg are persecuted beyond the routine dehumanization apportioned other inmates. The rightist policies of the staff are proverbial, and they profoundly fear anyone standing for justice and peace. God, flag, law, order, privilege, all mask a policy of falsehood to the men, petty persecution, and at worst, brutality of an impressive type. Meanwhile, official propaganda boasts of rehabilitation—of tolerance, humaneness and creative innovation. In reality, policy toward the men faithfully repeats the government’s duplicity, broken promises and eager resort to naked force. The federal penal system is part of “big government” and is no better than that other. Prisoners are powerless colonials, not citizens, condemned for their crimes to the crime of punishment, from which there is little redress. They get the same essential treatment as blacks or Indochinese.

“Consequently,” he concludes, “I reject punishment, I refuse work and go to the ‘hole.’ There I will begin a fast for the men here, for Americans and Vietnamese in Indochina, for exploited people everywhere—and for their misguided, fearful and inhumane oppressors.”

Daniel Berrigan, S.J.

Underground in America

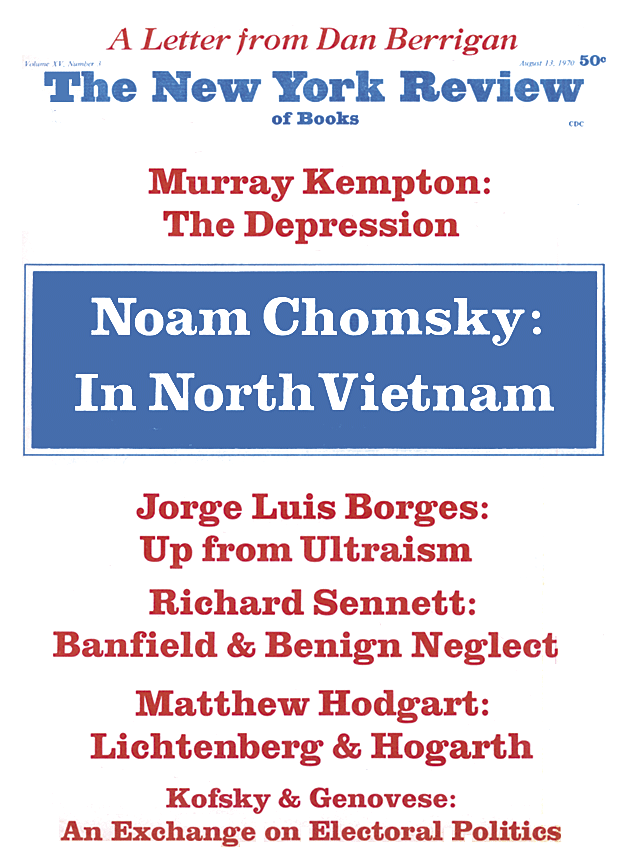

This Issue

August 13, 1970

-

*

The latest information is that they have been removed to the infirmary, but are still fasting. [Editors’ Note: Since this letter arrived we have been informed that, after many strong expressions of concern about their treatment, Father Berrigan and David Eberhardt have been released from solitary confinement and have broken their fast.] ↩