In response to:

Tragedy in Uruguay from the October 22, 1970 issue

To the Editors:

What is one expected to make of the declaration of the Central Governing Council of the University of the Republic of Uruguay, introduced by Jose Yglesias, and translated by Lee Lockwood, in the letters column of The New York Review of Books of October 22, on the killing of Dan Mitrione? The reader is given no information as to what the university is, what the Governing Council is, who composes it—whether students, professors, administrators, or lay citizens—how they are chosen, whether by election or appointment, what their political coloration is, and how seriously they are to be taken. To the reader acquainted only with American and European universities it is startling to see that a university “governing council” of any sort should publish statements on political events. Is this habitual, and if so, how did it come to pass? What is one expected to make of the final sentence: “The university has faith in the judgment of the Uruguayan people, and in their ability to be the makers of their own destiny,” when it is common knowledge that the Uruguayan government denounced in the statement is itself popularly elected under a constitution that guarantees civil liberties? The editors of The New York Review do not serve their readers well by giving space to such a document without any additional information.

Nathan Glazer

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Jose Yglesias replies:

The Governing Council of the University of the Republic of Uruguay is composed of the Rector of the university, the Vice Rector, and of representatives of the faculty and students from all the faculties of the university, elected by their peers. The university is endowed by the government but enjoys autonomy, and this method of running the university is not unrepresentative of universities in Latin America.

La Reforma, the university reform movement, began in Cordoba in 1918 (for Mr. Glazer’s sake, this Cordoba is in Argentina) and spread quickly through the continent. In 1910 there was much agitation in Uruguay about the separation of the university community from the social problems of the country, an argument heard lately about some United States universities, and owing to the success of this movement, as well as that of the Reforma, the Governing Council does take note, though infrequently I understand, of what is happening in the country.

The tone of the statement that Mr. Glazer questions is unusual for the Council, as is the directness with which it deals with political issues. In that lies its importance. One other reason is that this is the only university in Uruguay and its governing council can be said to speak for the country’s intellectuals. I don’t know the political coloration of the individuals on the Governing Council. I understand that the Rector is of socialist persuasion, and I daresay the others are to the left of Mr. Glazer, as are most Latin American intellectuals.

President Pacheco Areco of Uruguay was elected vice president three years ago and rose to the presidency on the death of the president in 1968. The election was held under a constitution much like our own; one could go further with this comparison and say that Uruguay is being governed by Spiro Agnew following Nixon’s death by natural causes. In 1968 the Socialist Party was suppressed, a year during which the country was decreed to be in a “state of siege” for most of the year and individual liberties and guarantees suspended, as happened after the death of Mitrione. Newspapers have been shut down; one, El Popular, was the organ of the Communist Party and another, El Debate, of a right-of-center party. The Minister of the Interior announced in April of this year that Uruguay is undergoing a civil war. I trust this will do as a start in Mr. Glazer’s education on Latin America.

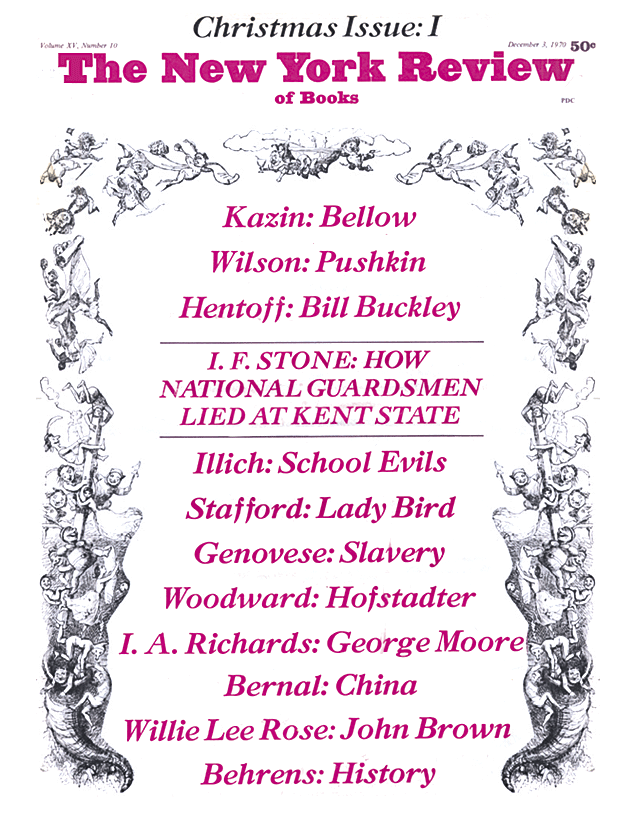

This Issue

December 3, 1970